HM Time Machine: JERONATON Interview

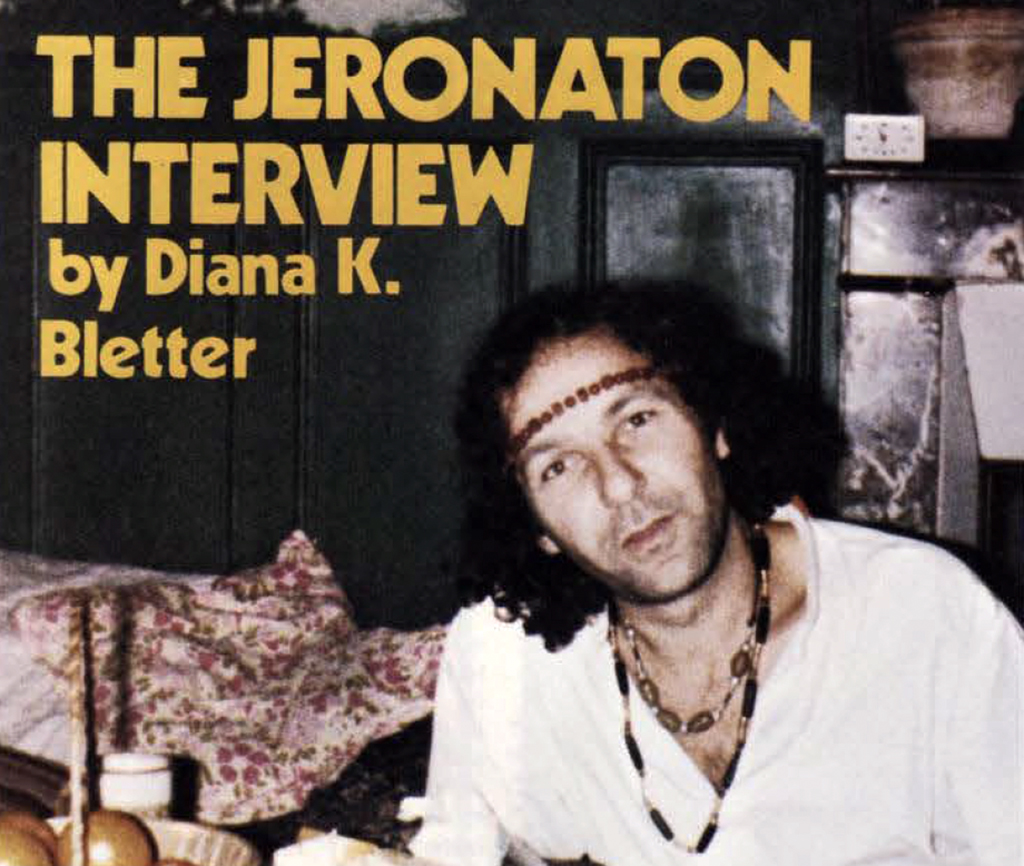

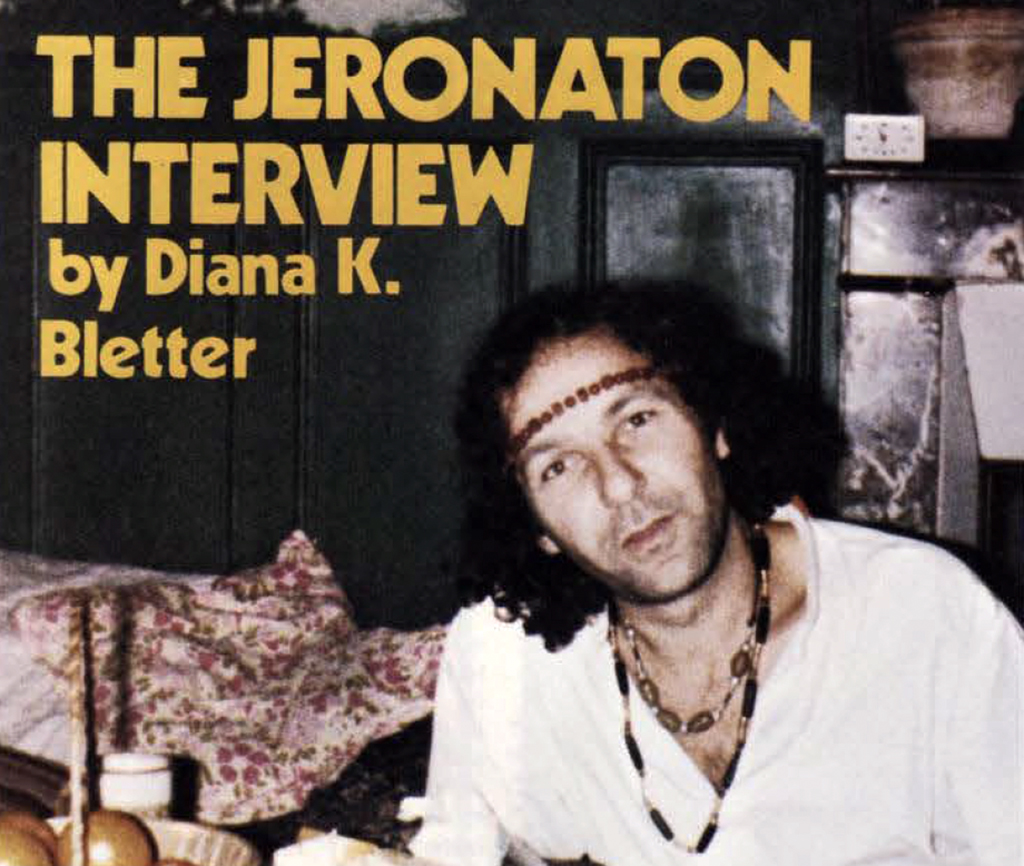

Jean Torton was born on September 4, 1942 in a small town in Belgium called Ghlen, but he insists that he is a "citizen of the world." He left Belgium more than ten years ago because of the "narrow-mindedness" of the people there and lived with friends and family on a farm in southern France. Since then, he has moved to Paris, where he works in a small studio.

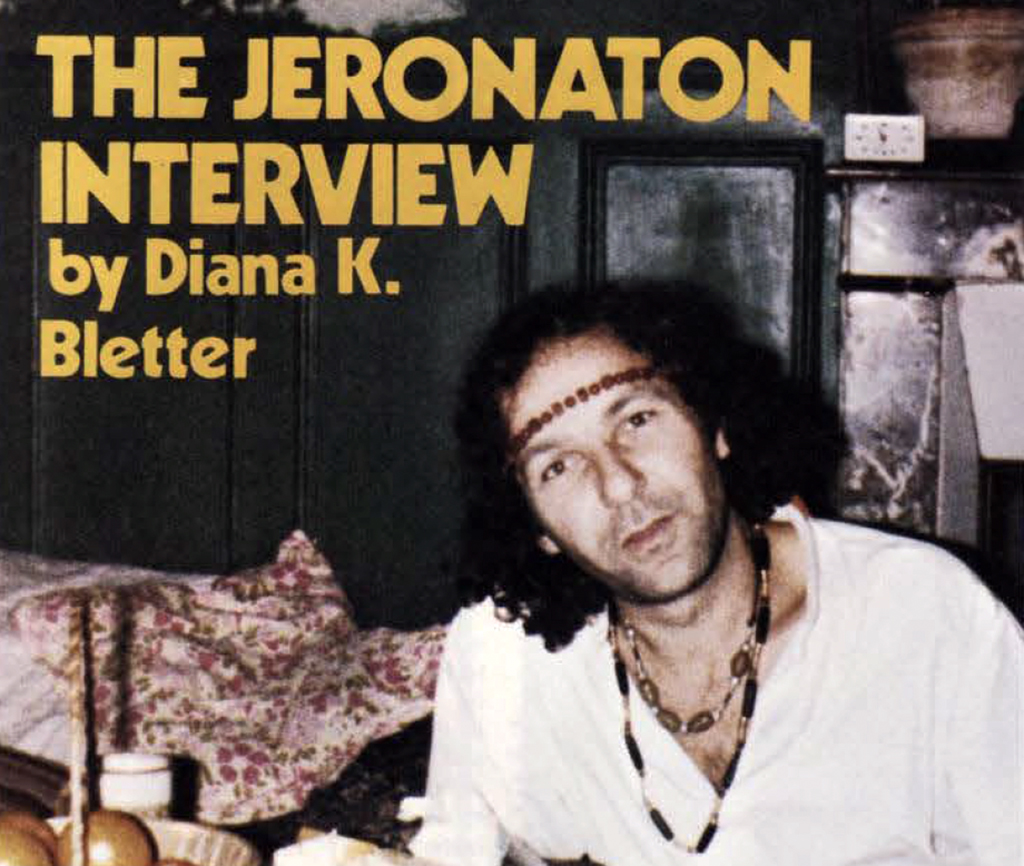

I didn't know what to expect when I went to his apartment in Fontenay-sous-Bois, a small town in the eastern suburbs of Paris. I definitely didn't expect to find someone who was such an image of the 1960s, or a "Baba-Kool" as they're called in French. Torton has shoulder-length curly hair, and when I met with him he was wearing a white Indian shirt, sandals (it was the middle of January), and strings of beads around his neck and forehead.

Torton, who changed his name to Jeronaton when he changed his style of drawing, seems to make his own universe no matter where he is. We had a dinner of brown rice, dark bread, and cabbage on a low table in the living room. In Paris, people never eat brown rice, dark bread, and cabbage on pillows in the living room.

A woman who works at the Metal Hurlant office told me that, "Torton lives a little in fantasy." She also told me, "You can't believe what he tells you." Maybe, but I'd like to think that all his stories, the ones he writes down and the ones he talks about, are true. Then again, I guess it doesn't really matter.

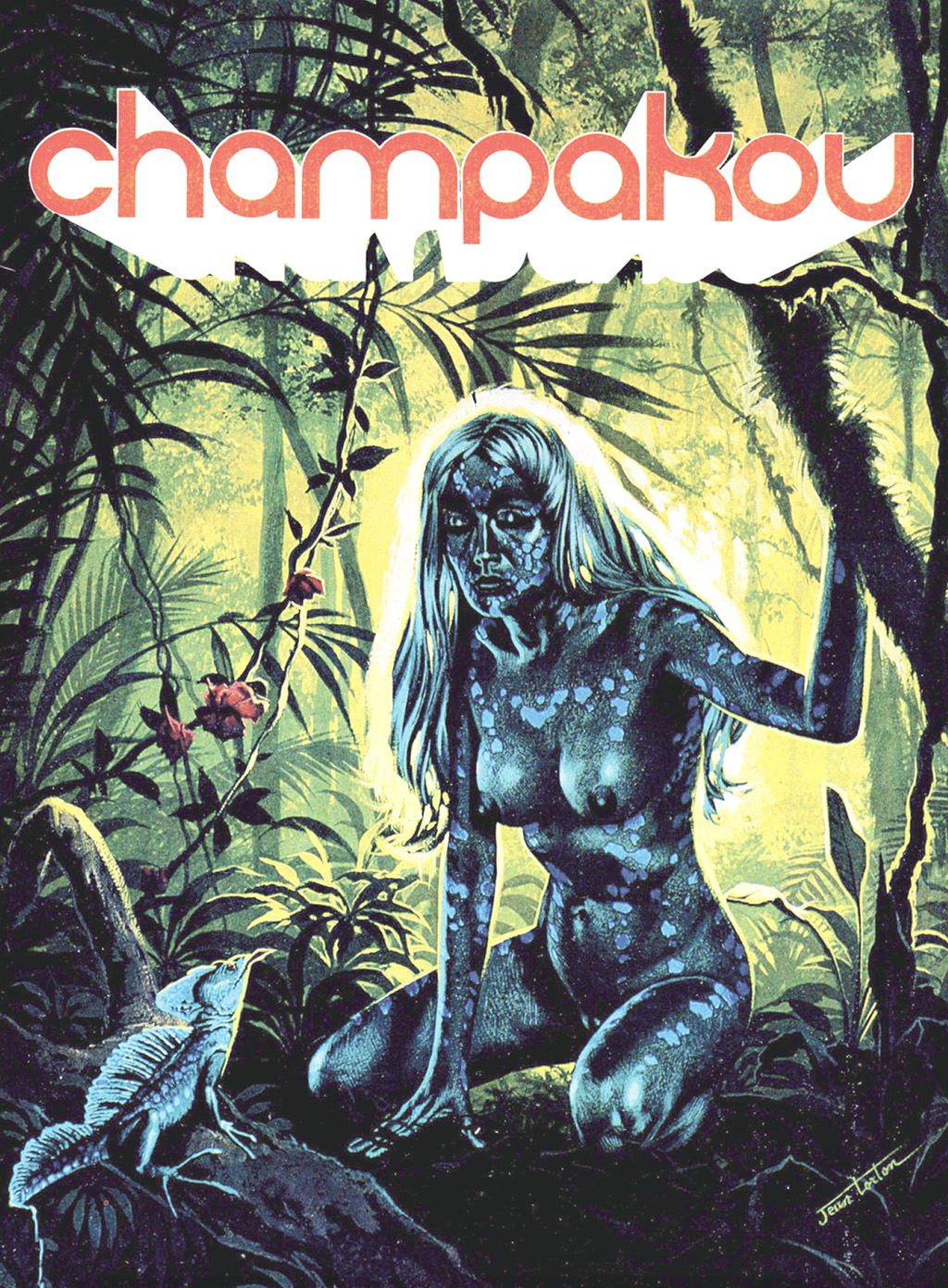

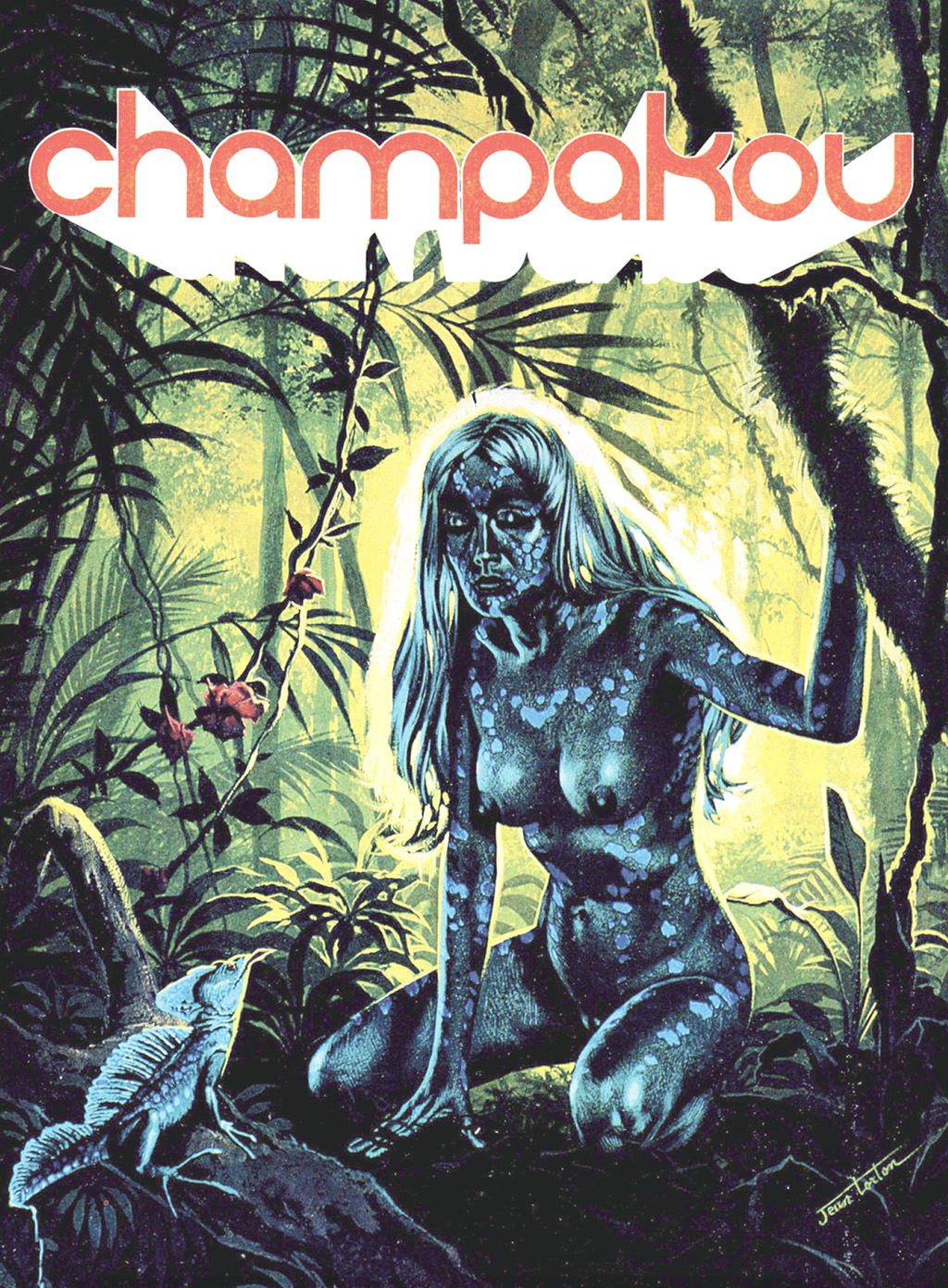

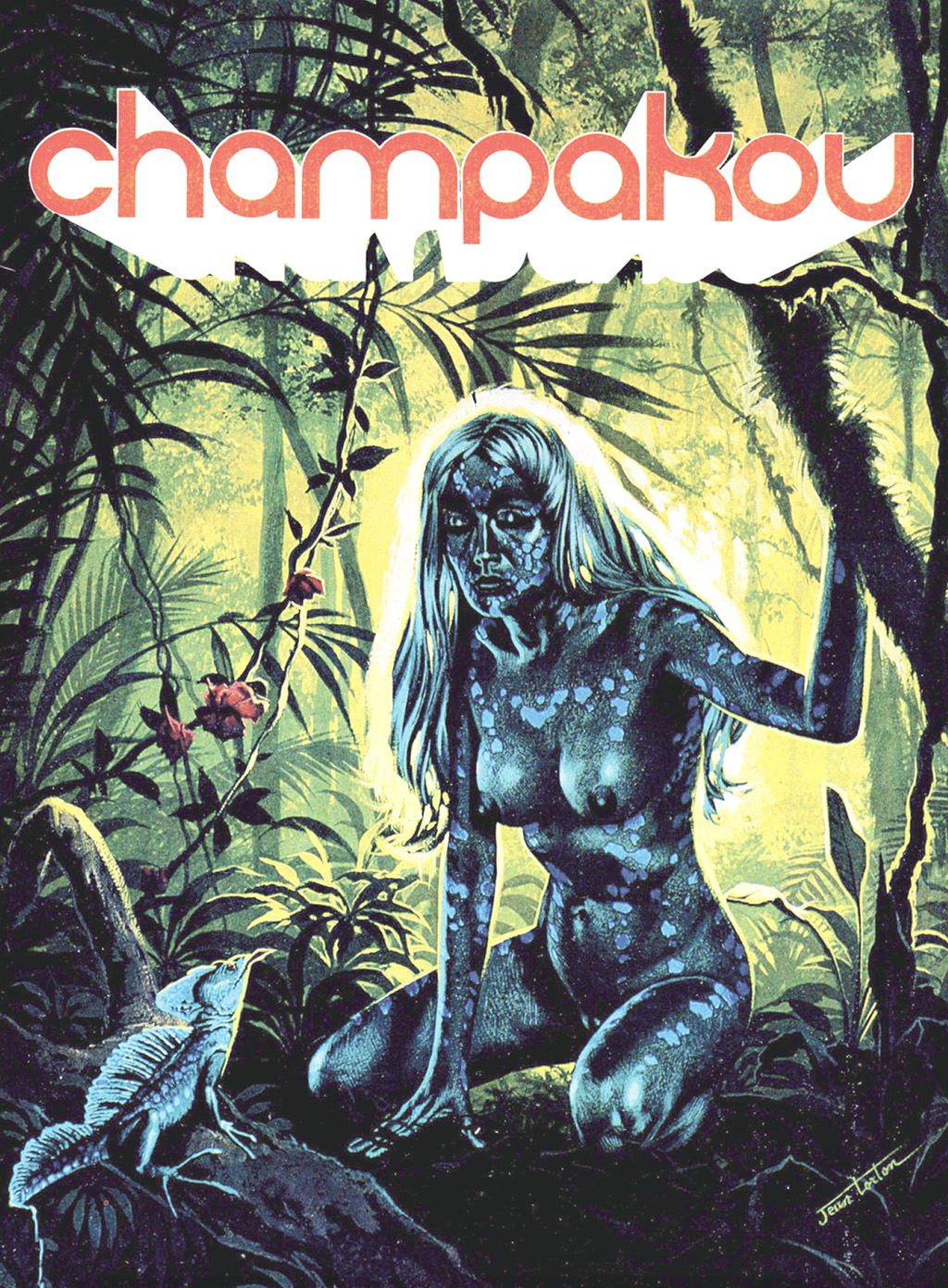

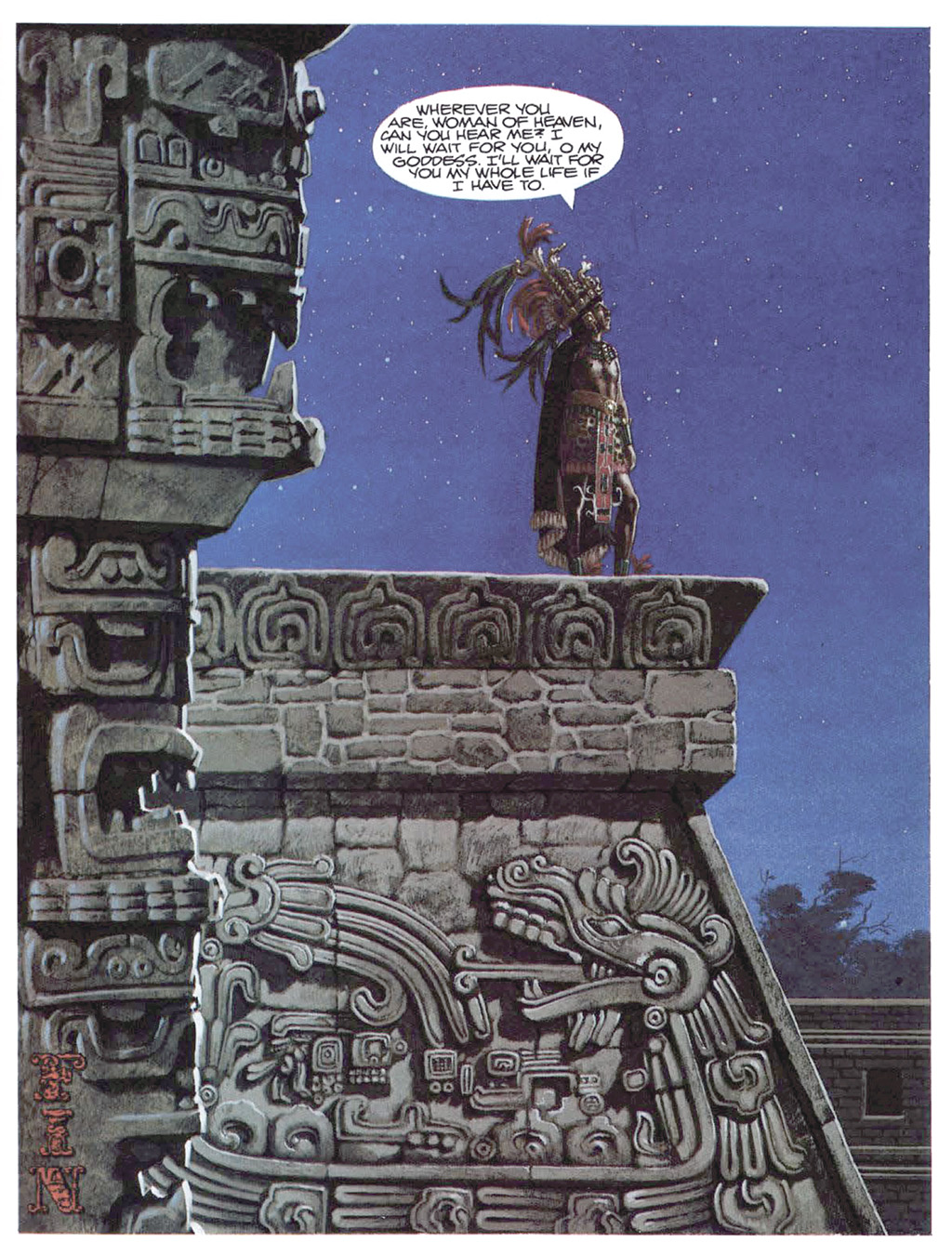

HEAVY METAL: The first question I want to ask you is something I've been thinking about since I read Champakou. Do you think there is any possibility that something like that could have really happened?

Jeronaton: I don't know. It's possible, but I'm not sure. It's true that they discovered some form of electricity 3,000 years ago, and they put up so many monuments that we couldn't even build today, but it's not that simple. For example, at San Maya there are designs and people might say, "Look, it's a man in a rocket; how did the Mayas know about that?" But it's only because they can't read the hieroglyphics. Someone who really knows the Mayan symbols would know that it's a mask of Lalac, the God of Rain. So it's not evident.

HM: So you don't "believe" in Champakou?

Jeronaton: I don't believe in anything absolutely. I believe only in life absolutely.

HM: But not in the life of this society. You're always looking for other ways to live.

Jeronaton: Because I'm not satisfied with this life. But I don't believe in many things.

HM: Do you believe in God?

Jeronaton: I believe in some sort of God, or better yet, I believe the world has a reason for being - it didn't make itself. The world is an experiment, but an experiment for whom and for what... I'm not sure.

HM: How did you become interested in the Mayan culture?

Jeronaton: I read a lot about it when I was little. It always fascinated me, and now I've just been in the center of India - where few people go, because you have to travel through dangerous forests to get there (there are tigers and other ferocious animals). I'd like to go back and spend more time there. They live the way they've been living for thousands of years.

HM: And they welcomed you there?

Jeronaton: Yes, because, for example, I read before I went there that the Indians never carry guns into the forest and disdain the white men who go through the forest carrying a lot of weapons. So I didn't carry anything, and when they saw that, they respected me and welcomed me.

HM: How did you start drawing?

Jeronaton: I've always drawn. At school I did nothing except make little designs and comic strips. Then I got sick of school and quit at seventeen. I was very lucky. We were talking about fate before, and I'll tell you what happened that makes me believe in it sometimes. I was going to show my comic strips to the magazine Tintin in Brussels, but I got lost and knocked on the door of the apartment that turned out to be that of Herge, the artist who draws the Tintin comic strip. Just luck, like that, because Brussels is a big city, you know. I started drawing at his house, he corrected some of the things I was doing, and I then published my first strip.

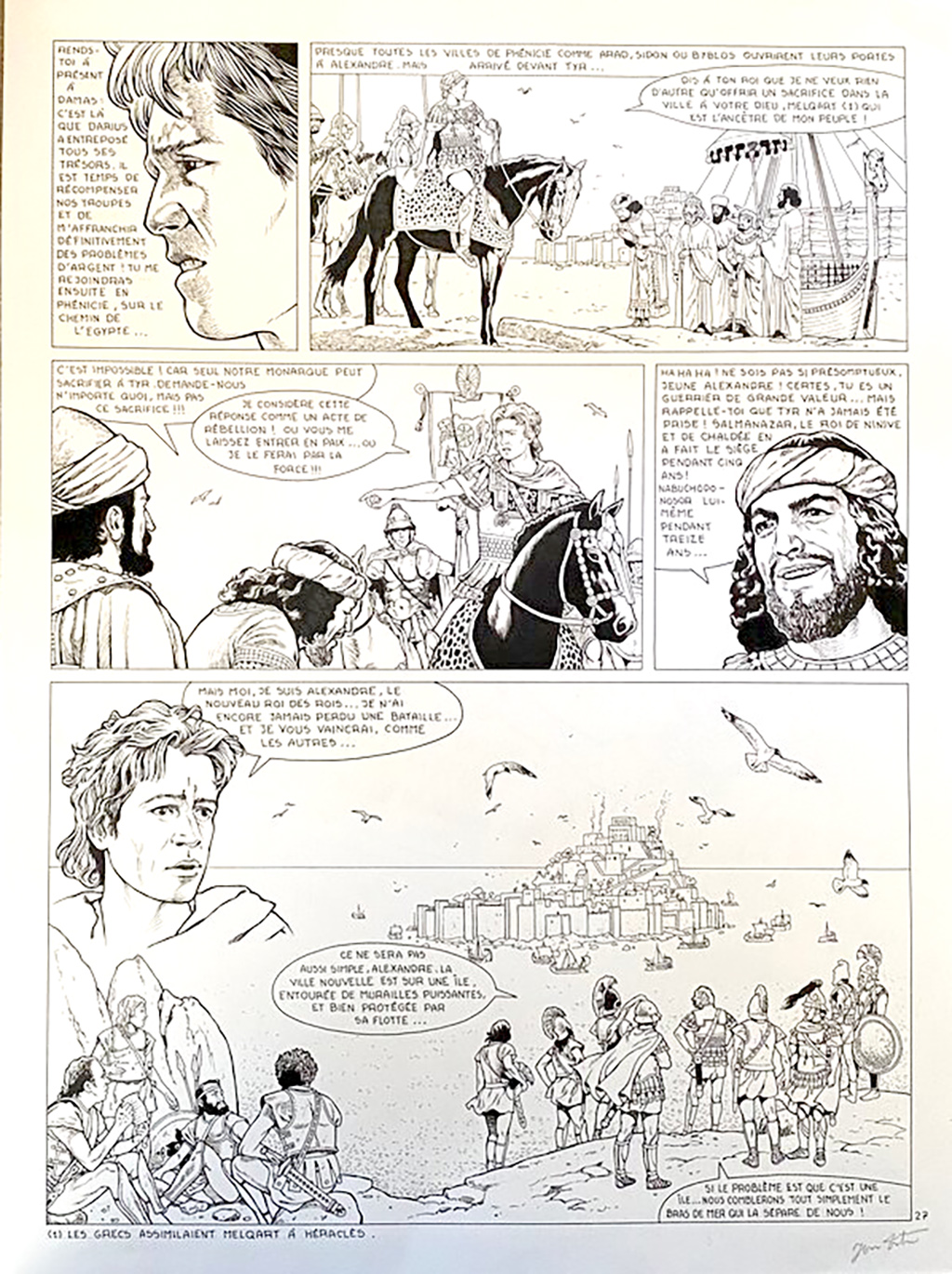

HM: What kind of strips did you draw at first?

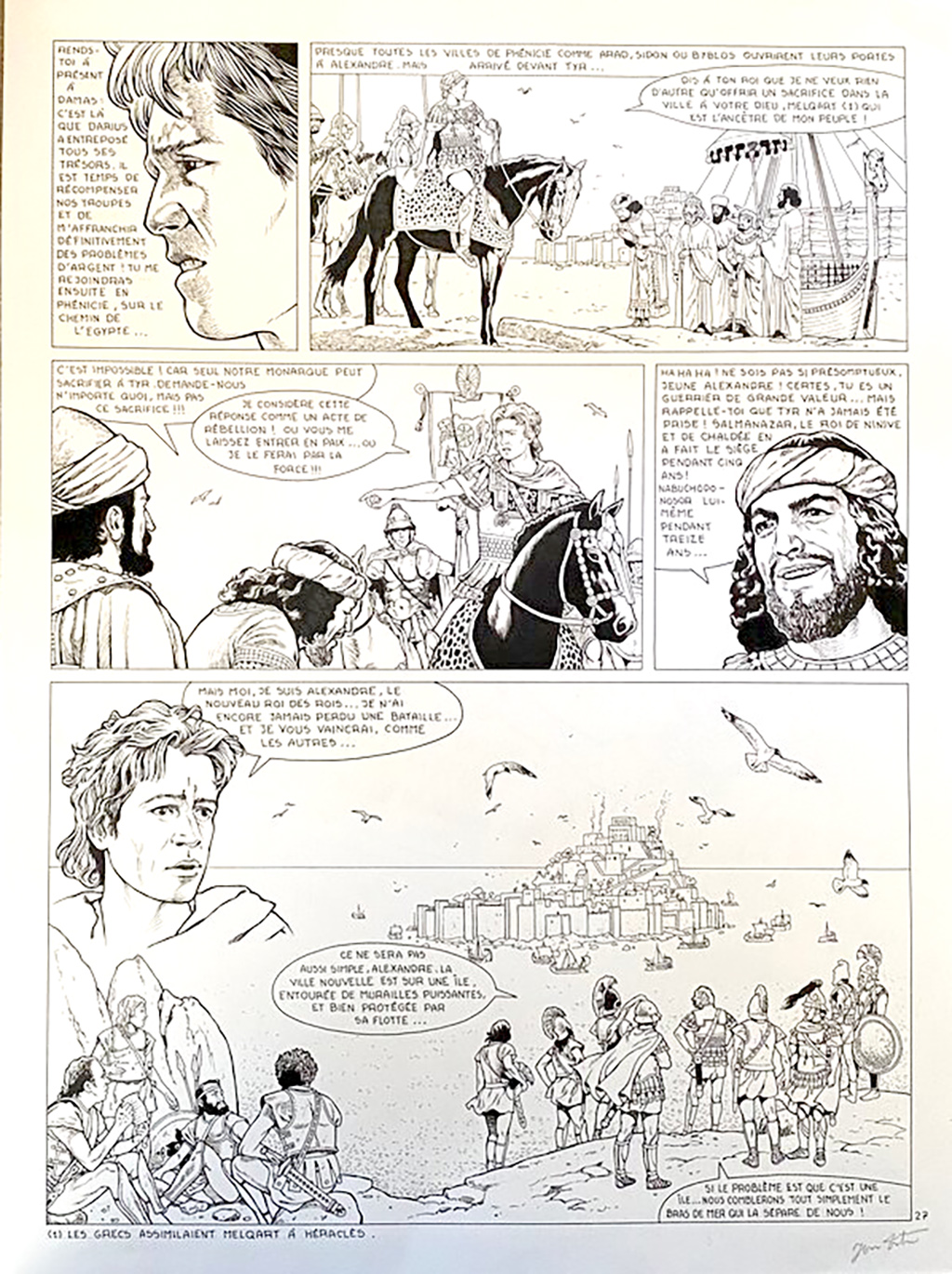

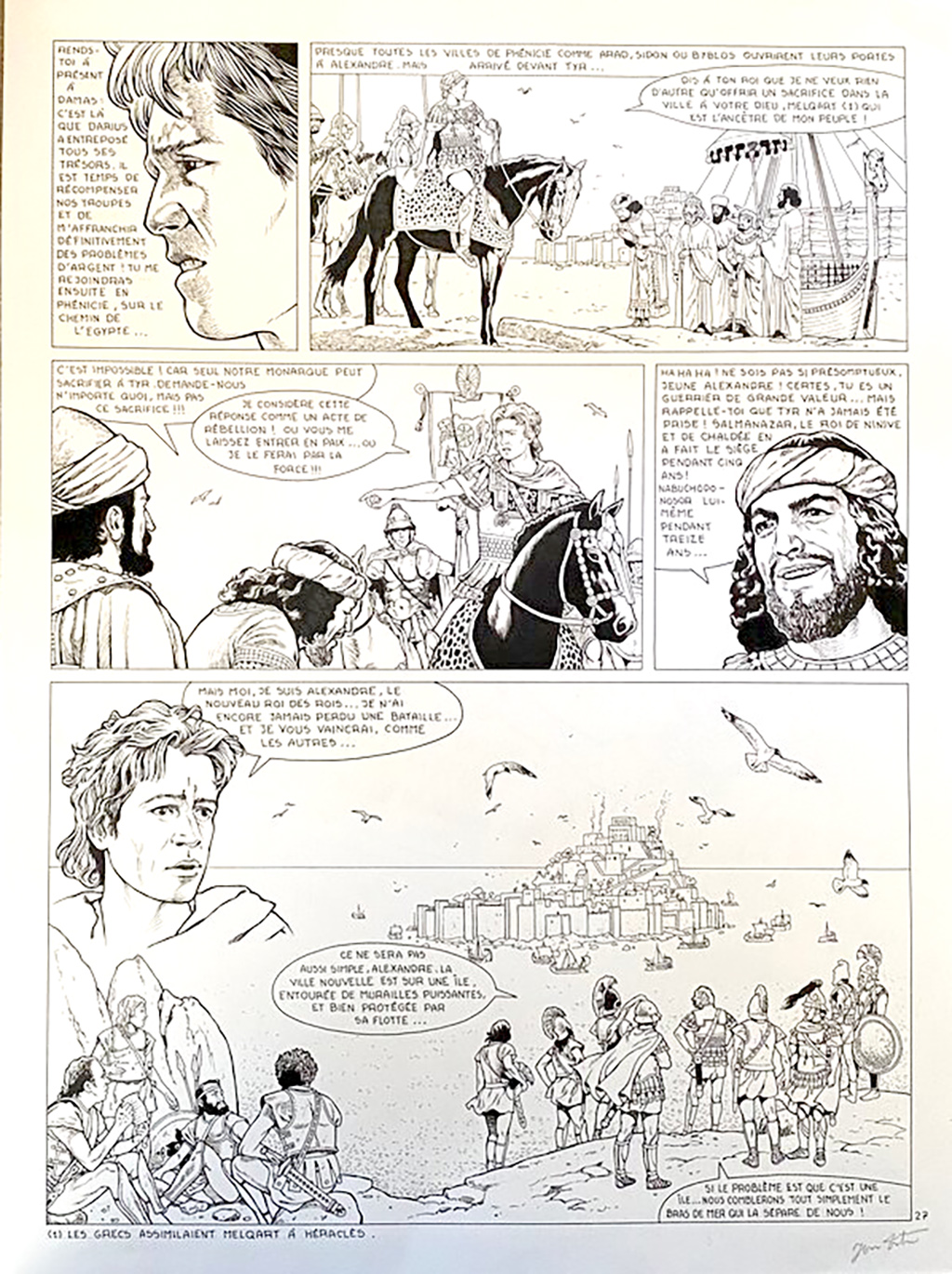

Jeronaton: I was doing historical comic strips for children, but it began to get very boring after a while.

HM: And that's how you started drawing science fiction?

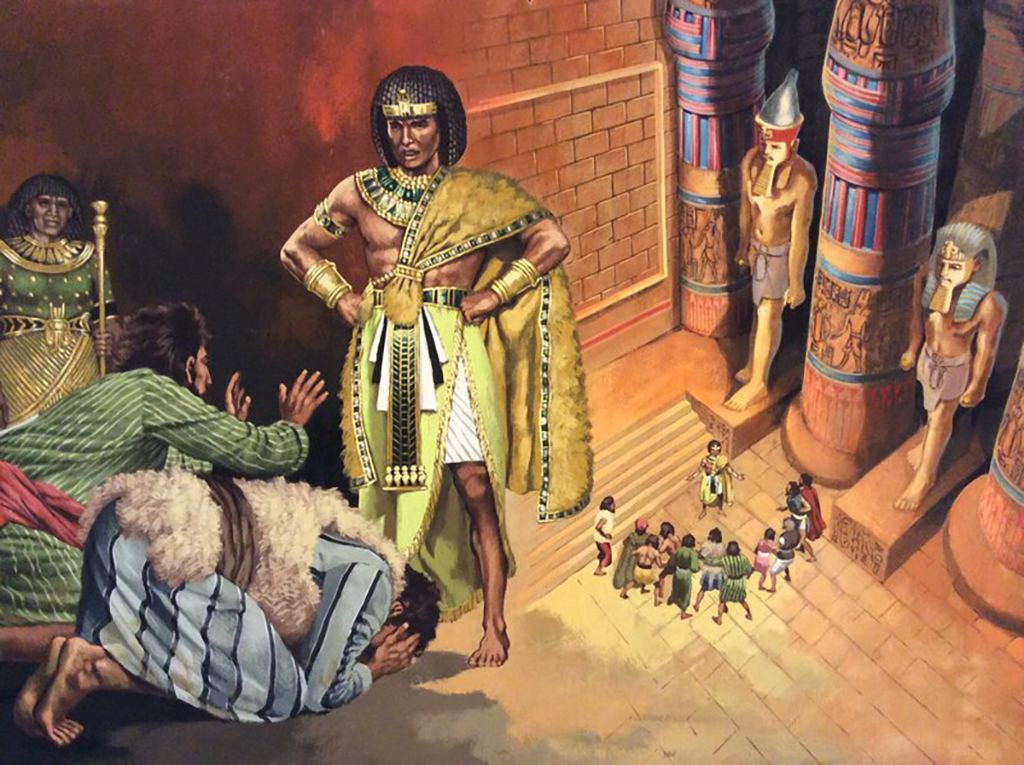

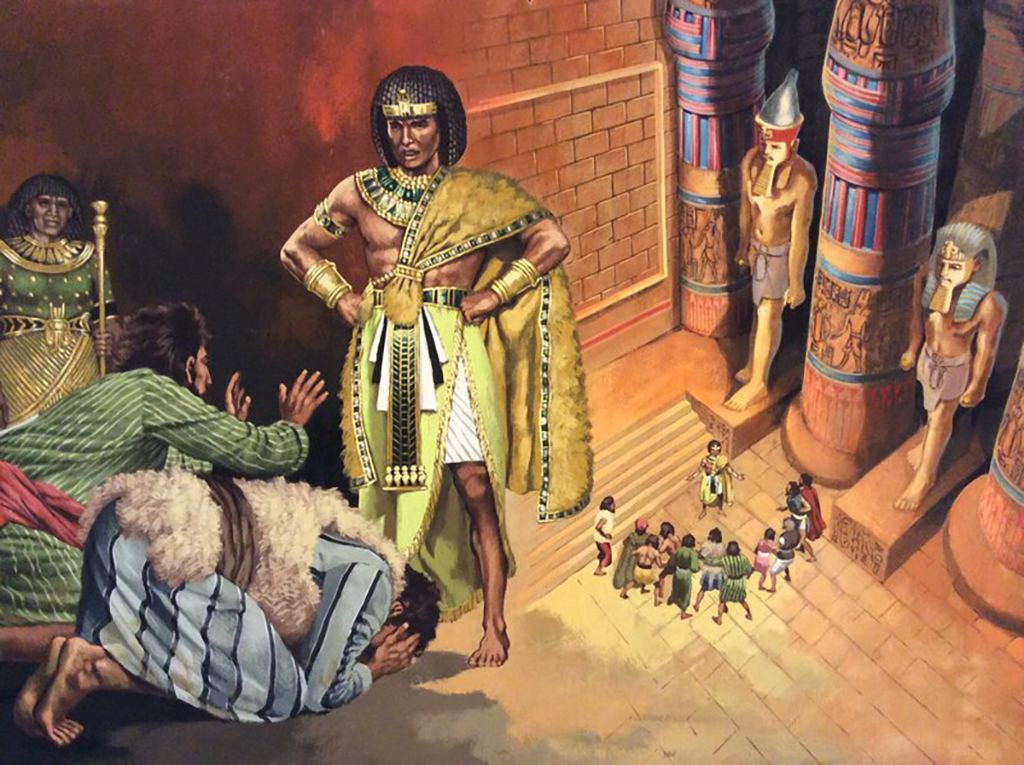

Jeronaton: No, at first I didn't know what to do. Then I decided to illustrate the Bible. In the Bible there is everything, and yet no one would be shocked. I worked on the illustrations for four years and it's yet to be published. It will come out sooner or later in ten volumes. When I finished that I made a list of everything I wanted to draw - nature, the Mayas, etc. and I made up the story of Champakou.

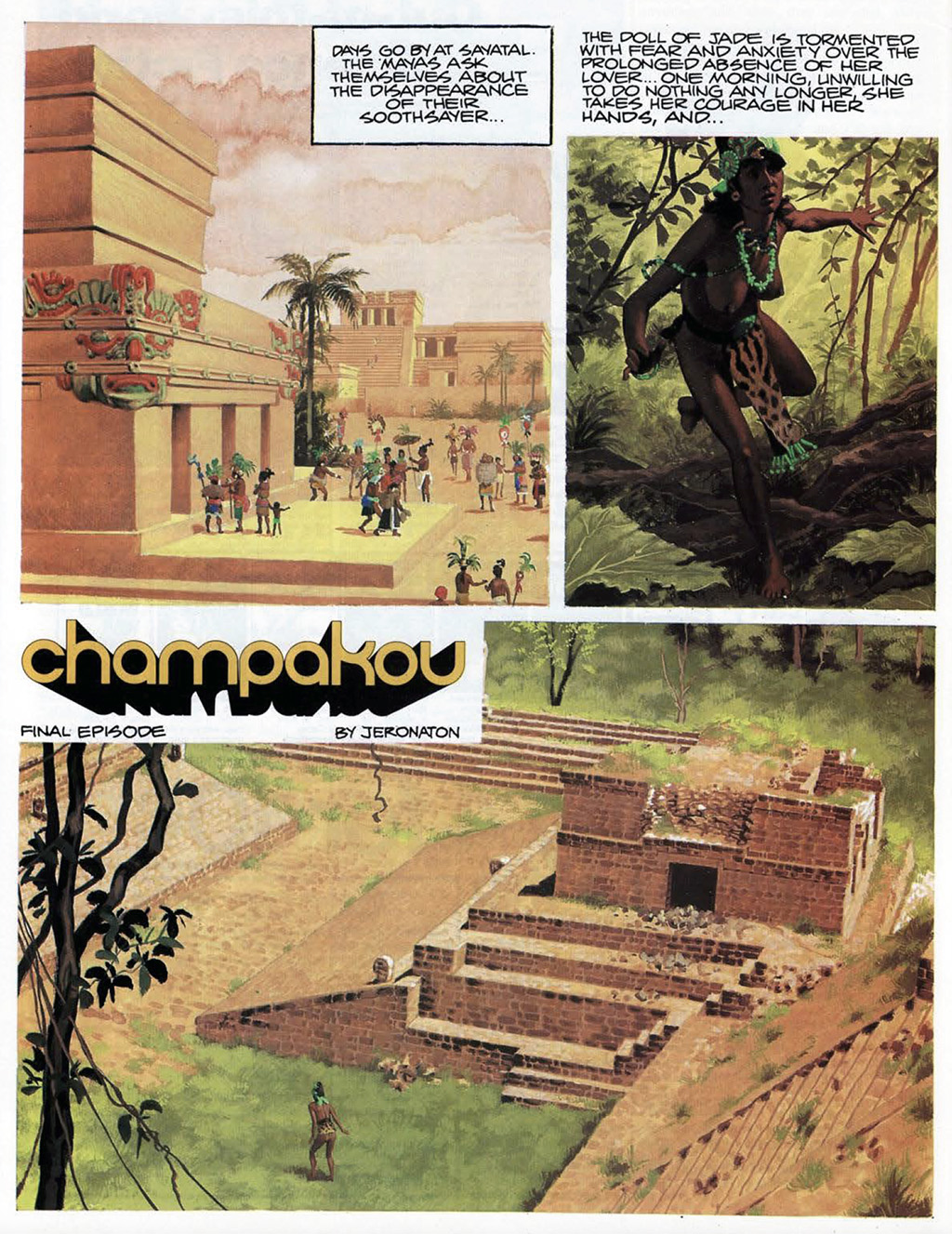

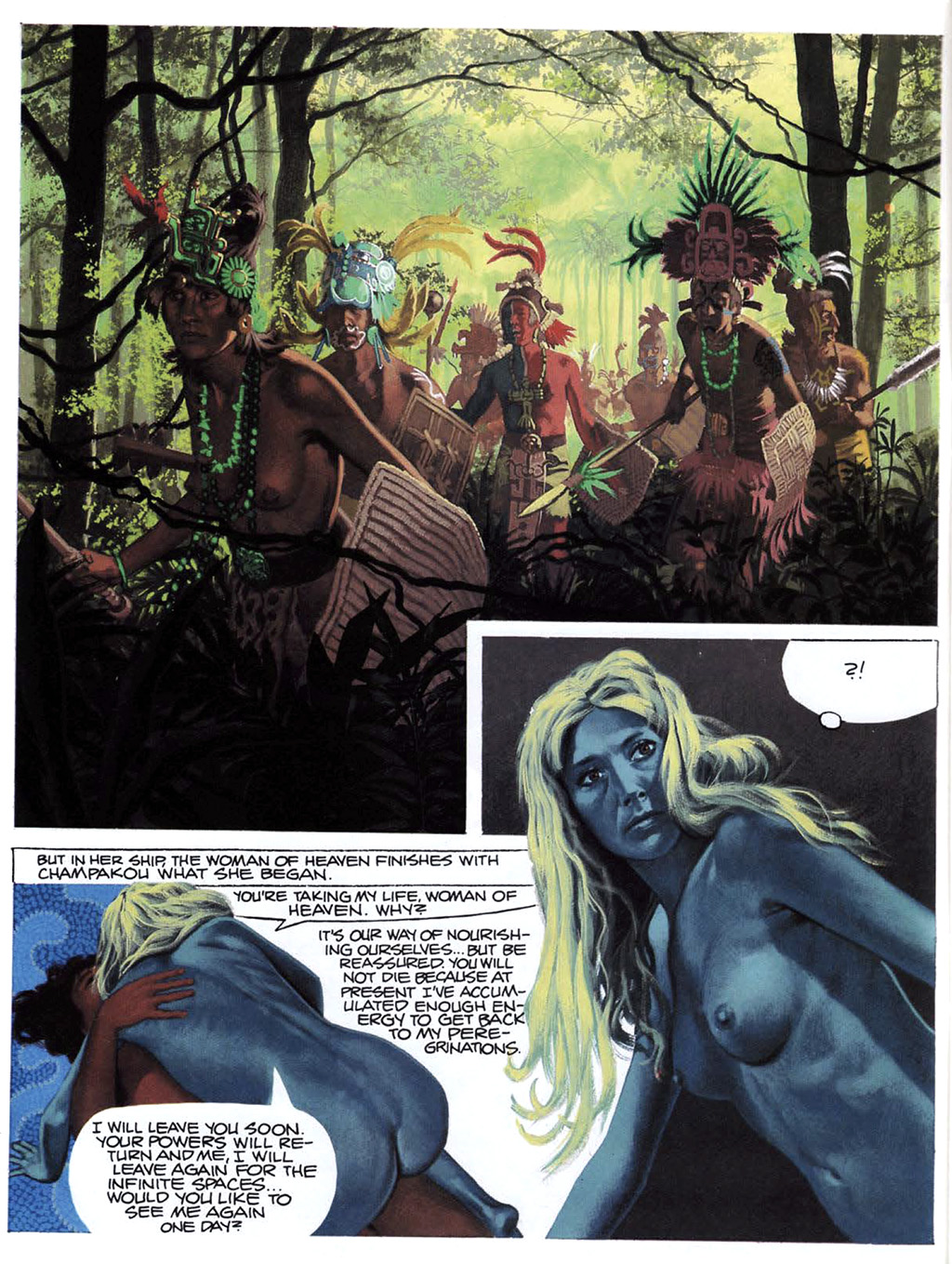

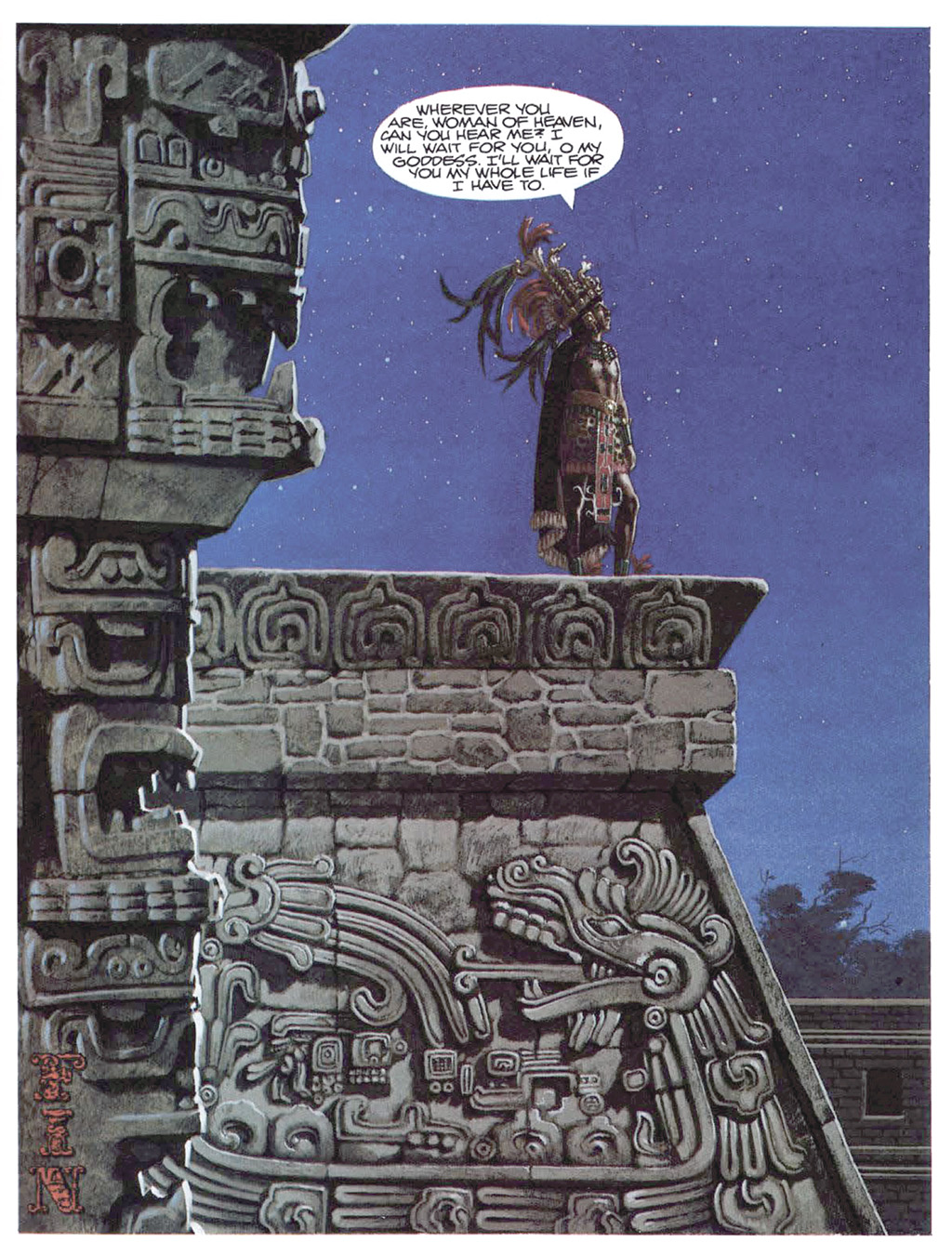

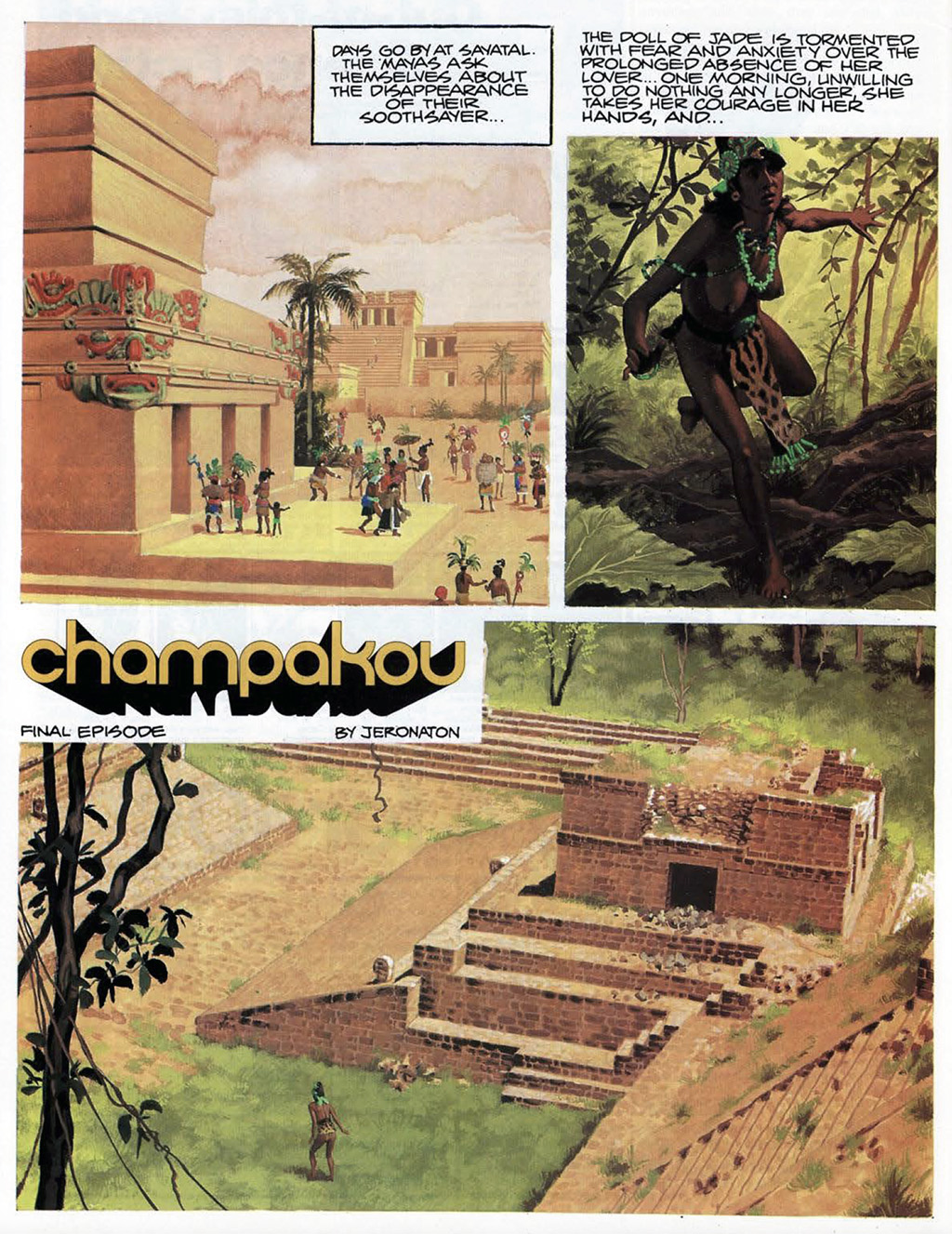

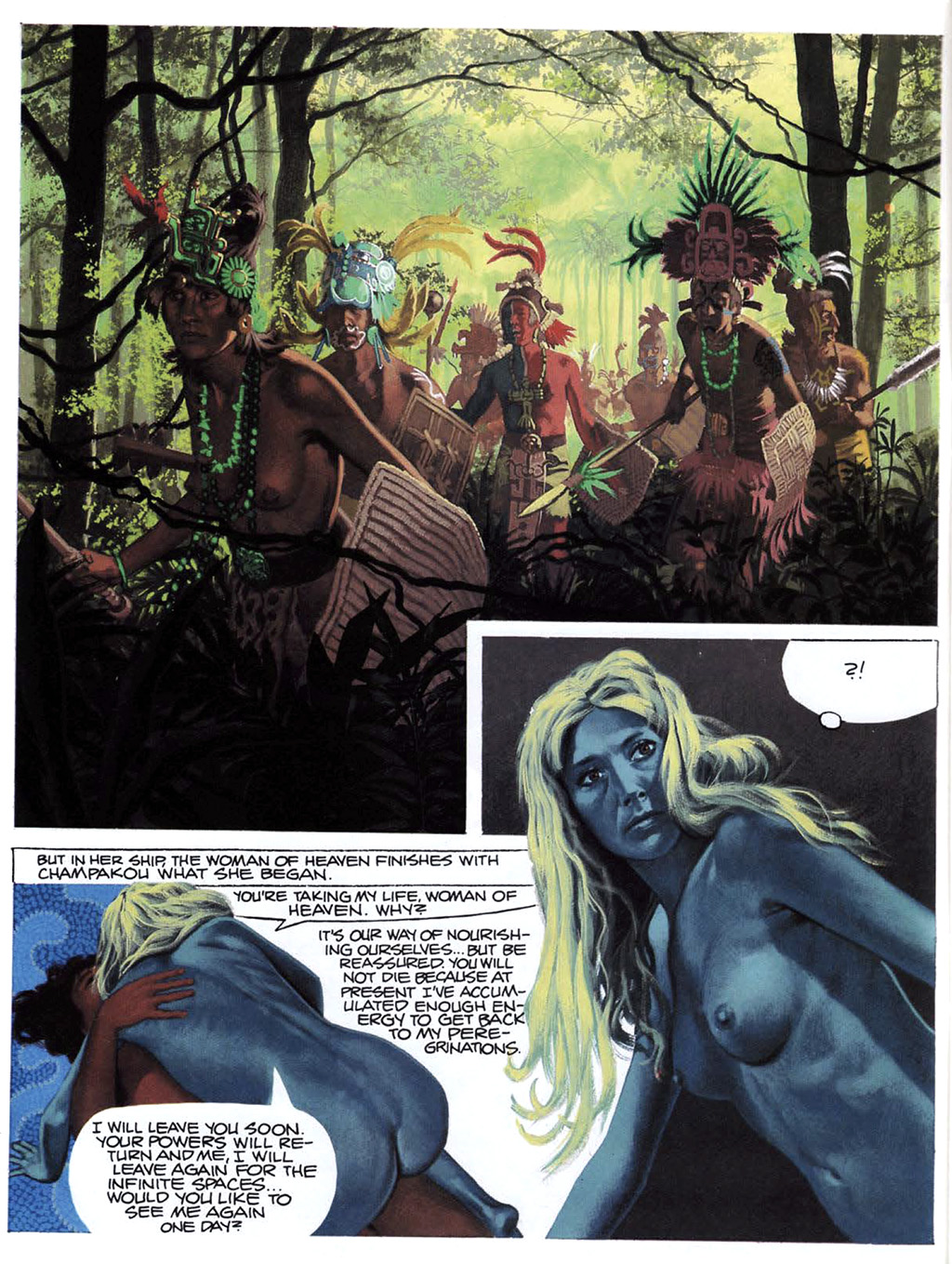

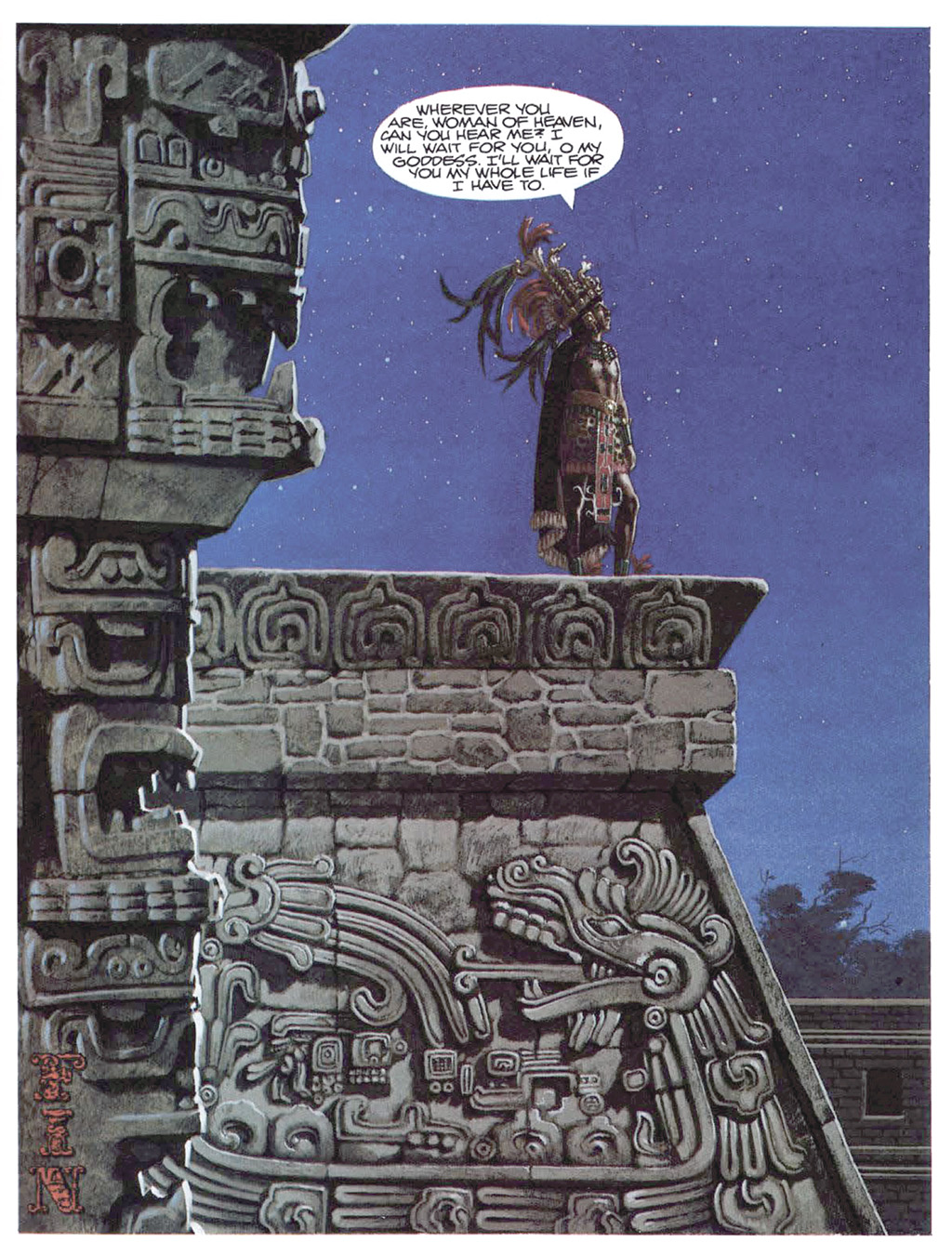

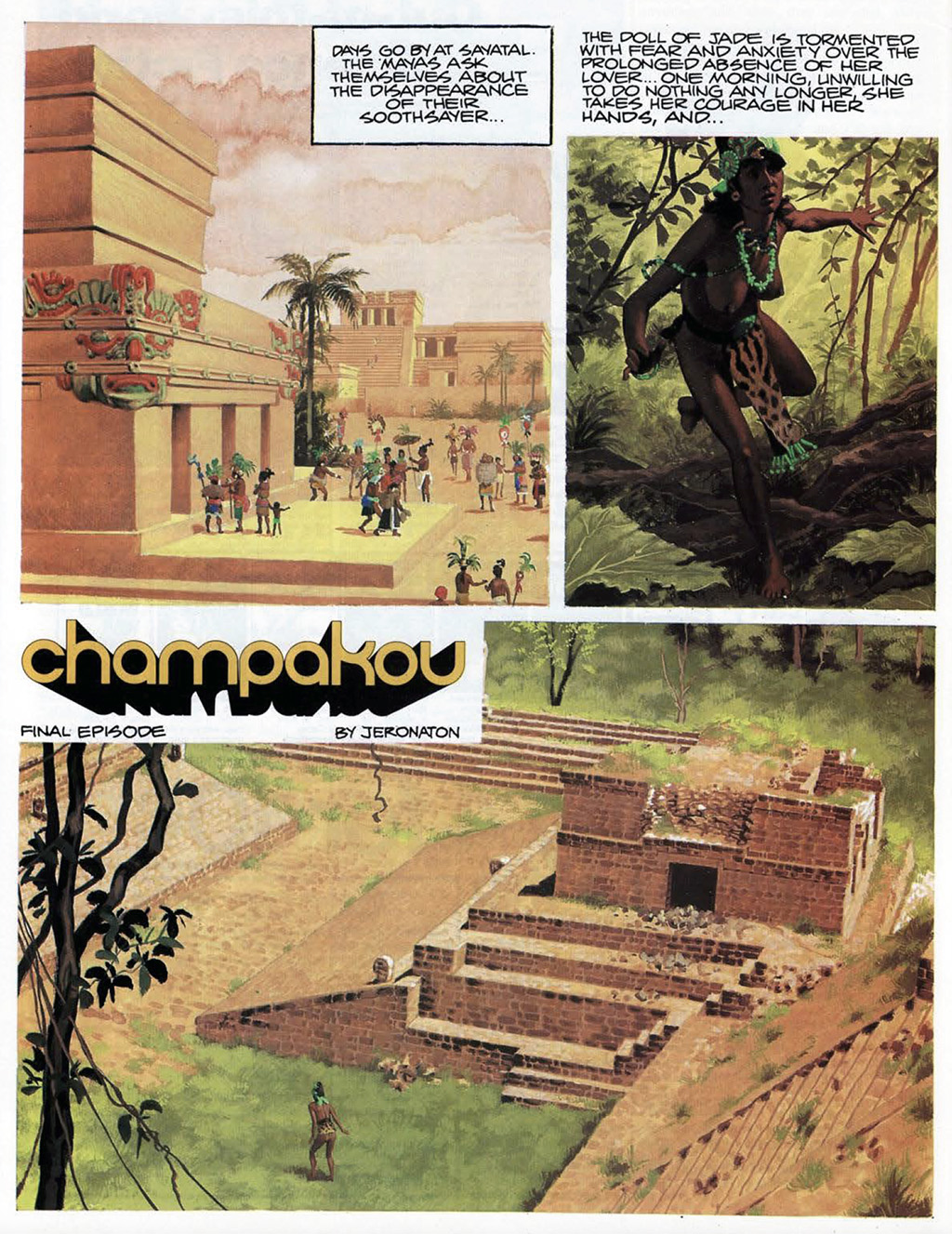

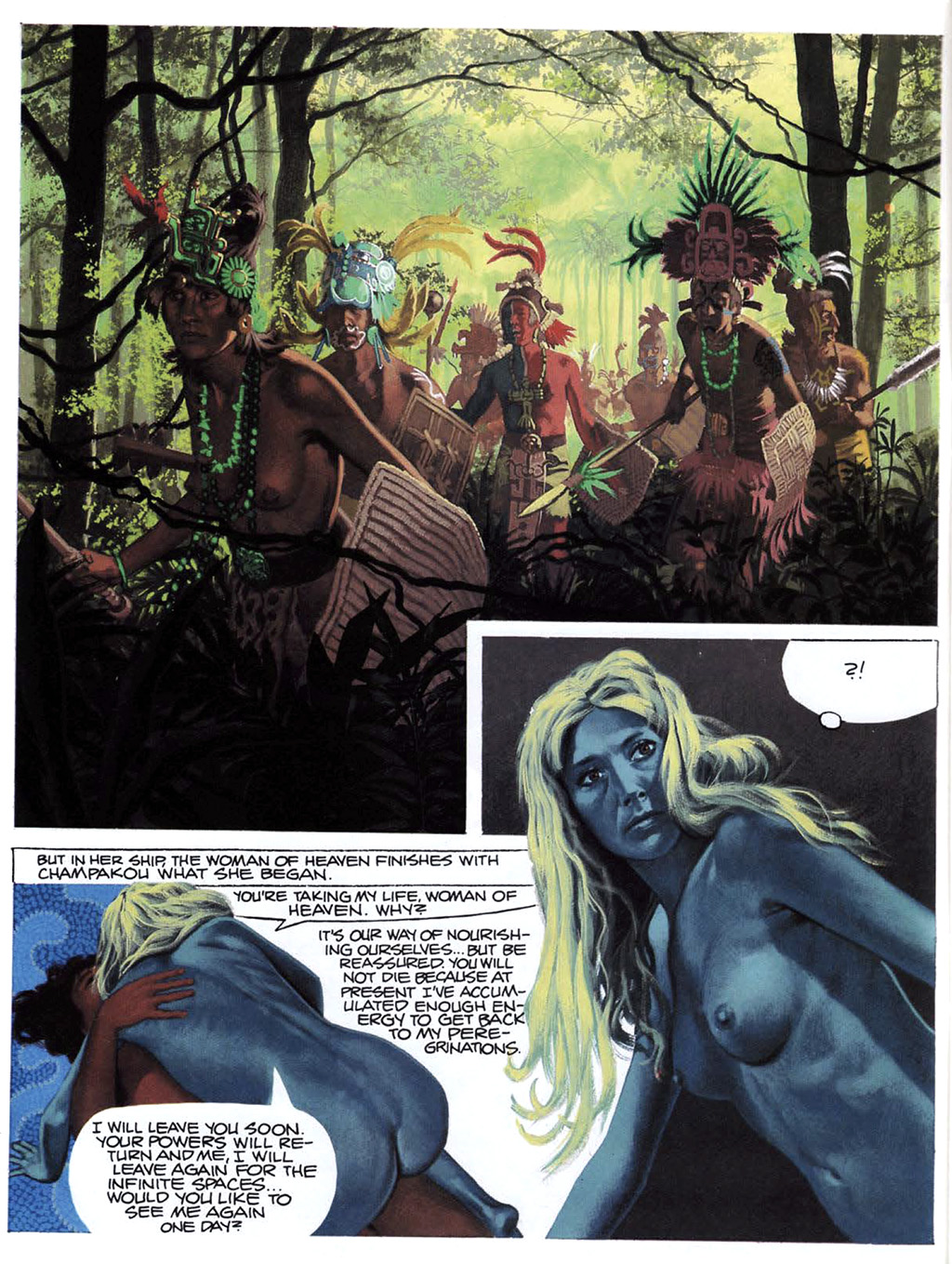

HM: How much of Champakou is real?

Jeronaton: The buildings, the clothes, the way they live and speak are all based on reality. In books I've read about their culture, but the rest is a dream. But you know reality goes further than fiction - it's often stranger.

HM: What has happened in your life that was stranger than what you've imagined?

Jeronaton: Ha, that's too personal.

HM: Have you ever had an adventure while you were traveling that was almost "science fiction"?

Jeronaton: No. I've had experiences that were passionate and dangerous but nothing that was almost science fiction. There are extraordinary things that have happened to me, but I can't tell everybody.

HM: You don't think that creating is opening yourself up to the public?

Jeronaton: Of course. You reveal your dreams, your frustrations, your ghosts, and your desires. You always create things you're concerned about. But there are things so personal that I don't tell people because it wouldn't interest them. For example, the Marquis de Sade told all his fantasies, but it's only people like him who can appreciate them.

HM: So what do you want to do for your readers?

Jeronaton: I'm not really sure. Comic strips are like television or the radio: they're not really worth anything. When I used to do historical strips there was always a moral for the reader. For example, I did a story about Spartacus, who organized the slave rebellion, and I wanted to show how he was a good man. But it began to be difficult because people want everything in simplistic terms. They want the good people to be on one side and the bad to be on the other, but everyone is a mixture of good and bad. It's hard to have nuances; people don't want to complicate their lives.

HM: Have you ever had a "'close encounter of the third kind"?

Jeronaton: No, if I had, I'd know a lot more [laughter]. As it is, I hardly know anything.

HM: What about seeing a UFO?

Jeronaton: Well, one time someone told me about a UFO that was seen in the south of France. It had been photographed, and pictures even appeared in some newspapers. The following year I went camping there with my children and some friends, and the same day, the following year, we saw the UFO that was spotted the year before. We returned the following year, the same day, but we didn't see anything. Have you ever?

HM: Now you're interviewing me?

Jeronaton: Yes.

HM: Well, one time when I was younger I saw a white light pass by my bedroom window.

Jeronaton: And it couldn't have been an airplane?

HM: No.

Jeronaton: And did you have enough time to see it?

HM: Yes, but I've never been sure as to what it could have been. You know, after reading a story like Champakou, I would think that you would be less pragmatic and believe more in fantasy than you actually do. Your approach is rather scientific.

Jeronaton: The story is a dream, not at all real.

HM: Do you believe in fate?

Jeronaton: Yes, but I think that people can make their own fates. I used to think that nothing happened by chance, but now I'm not sure. I'd like to think we were created to be, or do, something here.

HM: Then you do believe in some kind of force?

Jeronaton: Yes, but I can't even imagine what it is. Ants can't imagine the world of men, so it's absurd to think that we can imagine some force beyond us. Einstein, before he died, said that the more research he did, the more he was sure there was a God and the more he was sure he'd never understand Him. I think it's the same for me.

HM: Do you ever take drugs?

Jeronaton: No, not anymore. I've tried, but now I'm against it. I smoked hash with the people in India every night, but here it's different. People go crazy with it here.

HM: Have you ever done drugs to change the way you draw or dream?

Jeronaton: No. I've never done them to escape reality.

HM: But you left Belgium, and you've said you want to return to India. Don't you think that's escaping reality?

Jeronaton: No. If you are living a sad reality, fortunately, you can change it. Everything you do you merit, or else you pay dearly. People who don't take their lives into their own hands, then blame the government, the society, or other people, they don't do anything for themselves.

HM: How do you think the world will end?

Jeronaton: Either there will be a nuclear war (as the Bible and other religious texts predicted: the world would end in fire), or people will learn to change.

HM: Do you believe in "I think, therefore I am"?

Jeronaton: Yes. I'm conscious, therefore I am.

HM: Do you think there's life on other planets?

Jeronaton: It's more absurd to think there's no life on other planets.

HM: What do you plan to do in the future?

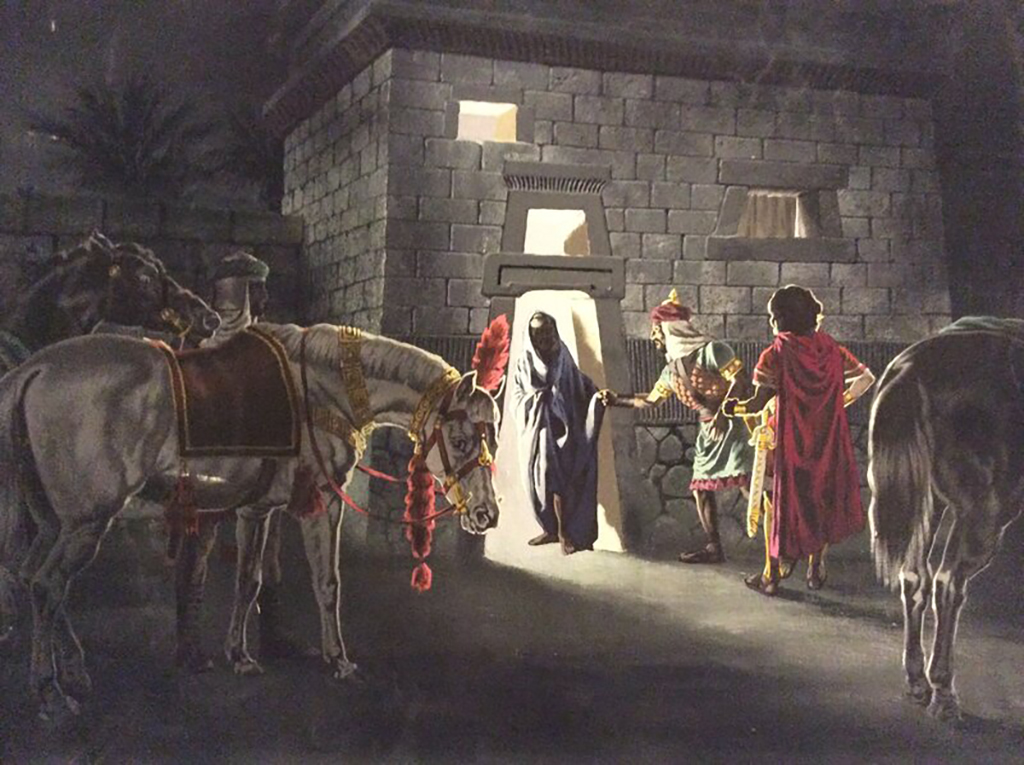

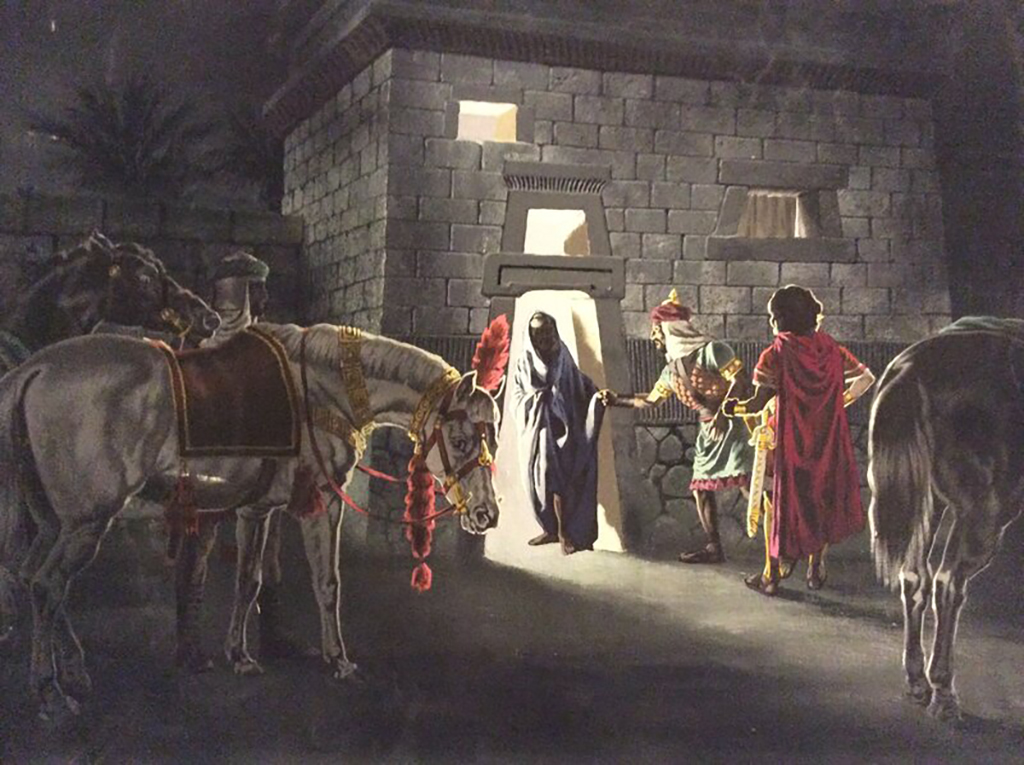

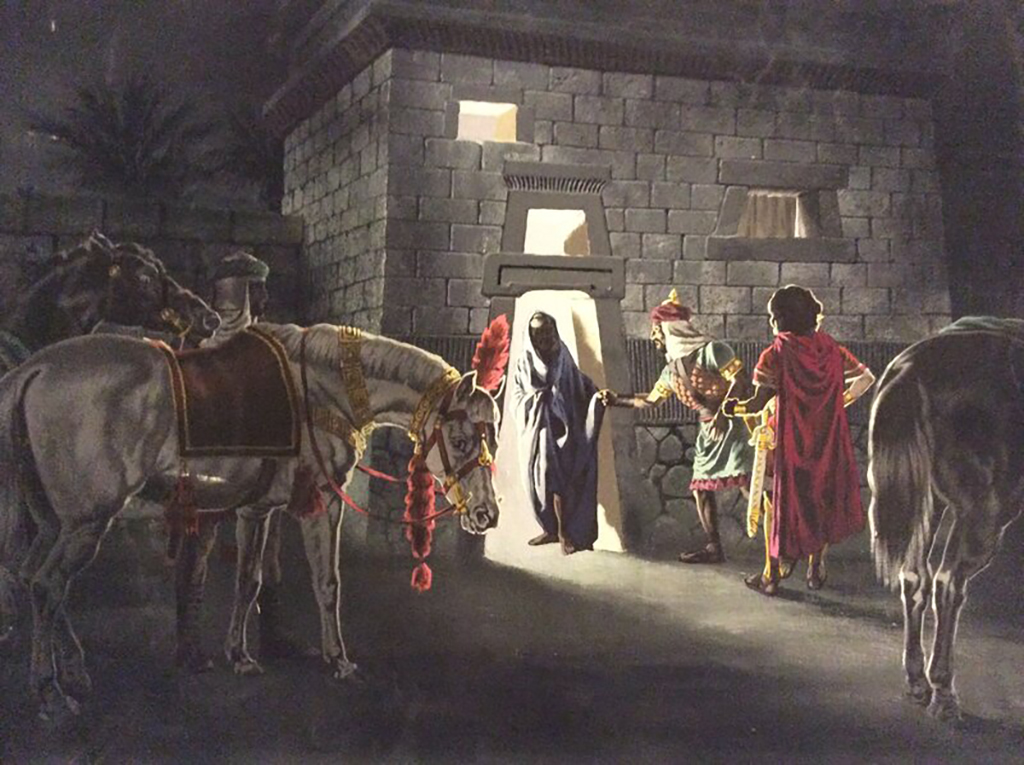

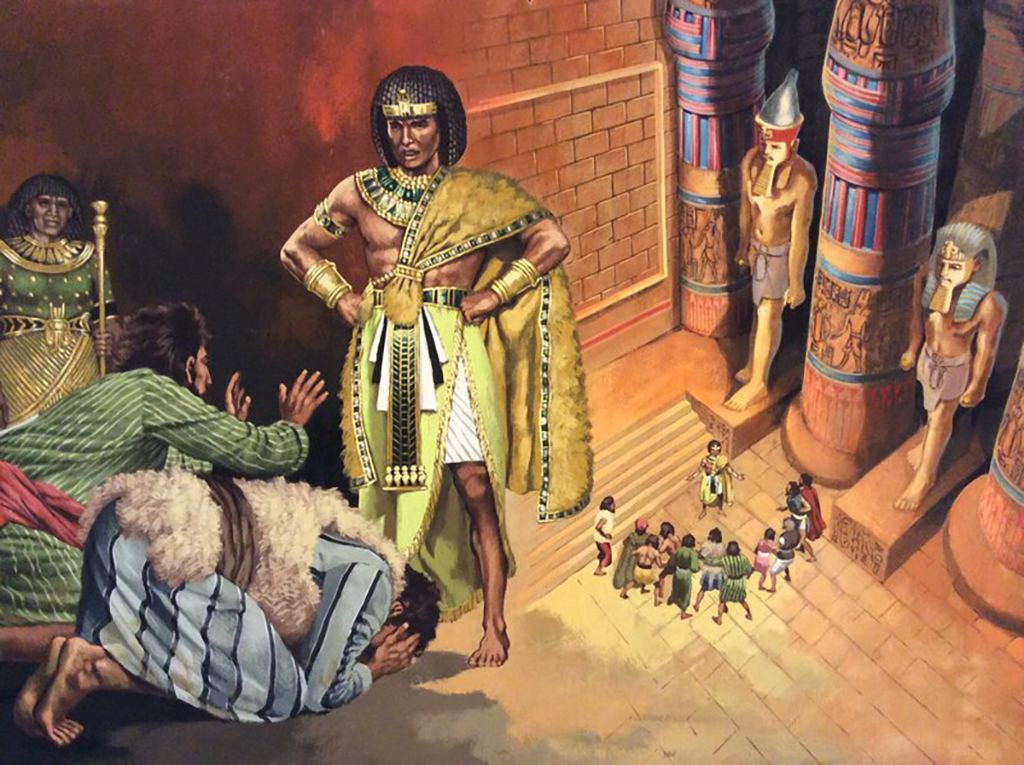

Jeronaton: I'd like to do something in the Egyptian epoch, not historic, but fantastic. I like traveling to different places and then doing stories about those civilizations.

HM: One final question: What is the most important thing for you in your life?

Jeronaton: That's easy. To be happy.

HM Time Machine: JERONATON Interview

Jean Torton was born on September 4, 1942 in a small town in Belgium called Ghlen, but he insists that he is a "citizen of the world." He left Belgium more than ten years ago because of the "narrow-mindedness" of the people there and lived with friends and family on a farm in southern France. Since then, he has moved to Paris, where he works in a small studio.

I didn't know what to expect when I went to his apartment in Fontenay-sous-Bois, a small town in the eastern suburbs of Paris. I definitely didn't expect to find someone who was such an image of the 1960s, or a "Baba-Kool" as they're called in French. Torton has shoulder-length curly hair, and when I met with him he was wearing a white Indian shirt, sandals (it was the middle of January), and strings of beads around his neck and forehead.

Torton, who changed his name to Jeronaton when he changed his style of drawing, seems to make his own universe no matter where he is. We had a dinner of brown rice, dark bread, and cabbage on a low table in the living room. In Paris, people never eat brown rice, dark bread, and cabbage on pillows in the living room.

A woman who works at the Metal Hurlant office told me that, "Torton lives a little in fantasy." She also told me, "You can't believe what he tells you." Maybe, but I'd like to think that all his stories, the ones he writes down and the ones he talks about, are true. Then again, I guess it doesn't really matter.

HEAVY METAL: The first question I want to ask you is something I've been thinking about since I read Champakou. Do you think there is any possibility that something like that could have really happened?

Jeronaton: I don't know. It's possible, but I'm not sure. It's true that they discovered some form of electricity 3,000 years ago, and they put up so many monuments that we couldn't even build today, but it's not that simple. For example, at San Maya there are designs and people might say, "Look, it's a man in a rocket; how did the Mayas know about that?" But it's only because they can't read the hieroglyphics. Someone who really knows the Mayan symbols would know that it's a mask of Lalac, the God of Rain. So it's not evident.

HM: So you don't "believe" in Champakou?

Jeronaton: I don't believe in anything absolutely. I believe only in life absolutely.

HM: But not in the life of this society. You're always looking for other ways to live.

Jeronaton: Because I'm not satisfied with this life. But I don't believe in many things.

HM: Do you believe in God?

Jeronaton: I believe in some sort of God, or better yet, I believe the world has a reason for being - it didn't make itself. The world is an experiment, but an experiment for whom and for what... I'm not sure.

HM: How did you become interested in the Mayan culture?

Jeronaton: I read a lot about it when I was little. It always fascinated me, and now I've just been in the center of India - where few people go, because you have to travel through dangerous forests to get there (there are tigers and other ferocious animals). I'd like to go back and spend more time there. They live the way they've been living for thousands of years.

HM: And they welcomed you there?

Jeronaton: Yes, because, for example, I read before I went there that the Indians never carry guns into the forest and disdain the white men who go through the forest carrying a lot of weapons. So I didn't carry anything, and when they saw that, they respected me and welcomed me.

HM: How did you start drawing?

Jeronaton: I've always drawn. At school I did nothing except make little designs and comic strips. Then I got sick of school and quit at seventeen. I was very lucky. We were talking about fate before, and I'll tell you what happened that makes me believe in it sometimes. I was going to show my comic strips to the magazine Tintin in Brussels, but I got lost and knocked on the door of the apartment that turned out to be that of Herge, the artist who draws the Tintin comic strip. Just luck, like that, because Brussels is a big city, you know. I started drawing at his house, he corrected some of the things I was doing, and I then published my first strip.

HM: What kind of strips did you draw at first?

Jeronaton: I was doing historical comic strips for children, but it began to get very boring after a while.

HM: And that's how you started drawing science fiction?

Jeronaton: No, at first I didn't know what to do. Then I decided to illustrate the Bible. In the Bible there is everything, and yet no one would be shocked. I worked on the illustrations for four years and it's yet to be published. It will come out sooner or later in ten volumes. When I finished that I made a list of everything I wanted to draw - nature, the Mayas, etc. and I made up the story of Champakou.

HM: How much of Champakou is real?

Jeronaton: The buildings, the clothes, the way they live and speak are all based on reality. In books I've read about their culture, but the rest is a dream. But you know reality goes further than fiction - it's often stranger.

HM: What has happened in your life that was stranger than what you've imagined?

Jeronaton: Ha, that's too personal.

HM: Have you ever had an adventure while you were traveling that was almost "science fiction"?

Jeronaton: No. I've had experiences that were passionate and dangerous but nothing that was almost science fiction. There are extraordinary things that have happened to me, but I can't tell everybody.

HM: You don't think that creating is opening yourself up to the public?

Jeronaton: Of course. You reveal your dreams, your frustrations, your ghosts, and your desires. You always create things you're concerned about. But there are things so personal that I don't tell people because it wouldn't interest them. For example, the Marquis de Sade told all his fantasies, but it's only people like him who can appreciate them.

HM: So what do you want to do for your readers?

Jeronaton: I'm not really sure. Comic strips are like television or the radio: they're not really worth anything. When I used to do historical strips there was always a moral for the reader. For example, I did a story about Spartacus, who organized the slave rebellion, and I wanted to show how he was a good man. But it began to be difficult because people want everything in simplistic terms. They want the good people to be on one side and the bad to be on the other, but everyone is a mixture of good and bad. It's hard to have nuances; people don't want to complicate their lives.

HM: Have you ever had a "'close encounter of the third kind"?

Jeronaton: No, if I had, I'd know a lot more [laughter]. As it is, I hardly know anything.

HM: What about seeing a UFO?

Jeronaton: Well, one time someone told me about a UFO that was seen in the south of France. It had been photographed, and pictures even appeared in some newspapers. The following year I went camping there with my children and some friends, and the same day, the following year, we saw the UFO that was spotted the year before. We returned the following year, the same day, but we didn't see anything. Have you ever?

HM: Now you're interviewing me?

Jeronaton: Yes.

HM: Well, one time when I was younger I saw a white light pass by my bedroom window.

Jeronaton: And it couldn't have been an airplane?

HM: No.

Jeronaton: And did you have enough time to see it?

HM: Yes, but I've never been sure as to what it could have been. You know, after reading a story like Champakou, I would think that you would be less pragmatic and believe more in fantasy than you actually do. Your approach is rather scientific.

Jeronaton: The story is a dream, not at all real.

HM: Do you believe in fate?

Jeronaton: Yes, but I think that people can make their own fates. I used to think that nothing happened by chance, but now I'm not sure. I'd like to think we were created to be, or do, something here.

HM: Then you do believe in some kind of force?

Jeronaton: Yes, but I can't even imagine what it is. Ants can't imagine the world of men, so it's absurd to think that we can imagine some force beyond us. Einstein, before he died, said that the more research he did, the more he was sure there was a God and the more he was sure he'd never understand Him. I think it's the same for me.

HM: Do you ever take drugs?

Jeronaton: No, not anymore. I've tried, but now I'm against it. I smoked hash with the people in India every night, but here it's different. People go crazy with it here.

HM: Have you ever done drugs to change the way you draw or dream?

Jeronaton: No. I've never done them to escape reality.

HM: But you left Belgium, and you've said you want to return to India. Don't you think that's escaping reality?

Jeronaton: No. If you are living a sad reality, fortunately, you can change it. Everything you do you merit, or else you pay dearly. People who don't take their lives into their own hands, then blame the government, the society, or other people, they don't do anything for themselves.

HM: How do you think the world will end?

Jeronaton: Either there will be a nuclear war (as the Bible and other religious texts predicted: the world would end in fire), or people will learn to change.

HM: Do you believe in "I think, therefore I am"?

Jeronaton: Yes. I'm conscious, therefore I am.

HM: Do you think there's life on other planets?

Jeronaton: It's more absurd to think there's no life on other planets.

HM: What do you plan to do in the future?

Jeronaton: I'd like to do something in the Egyptian epoch, not historic, but fantastic. I like traveling to different places and then doing stories about those civilizations.

HM: One final question: What is the most important thing for you in your life?

Jeronaton: That's easy. To be happy.

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

Jean Torton was born on September 4, 1942 in a small town in Belgium called Ghlen, but he insists that he is a "citizen of the world." He left Belgium more than ten years ago because of the "narrow-mindedness" of the people there and lived with friends and family on a farm in southern France. Since then, he has moved to Paris, where he works in a small studio.

I didn't know what to expect when I went to his apartment in Fontenay-sous-Bois, a small town in the eastern suburbs of Paris. I definitely didn't expect to find someone who was such an image of the 1960s, or a "Baba-Kool" as they're called in French. Torton has shoulder-length curly hair, and when I met with him he was wearing a white Indian shirt, sandals (it was the middle of January), and strings of beads around his neck and forehead.

Torton, who changed his name to Jeronaton when he changed his style of drawing, seems to make his own universe no matter where he is. We had a dinner of brown rice, dark bread, and cabbage on a low table in the living room. In Paris, people never eat brown rice, dark bread, and cabbage on pillows in the living room.

A woman who works at the Metal Hurlant office told me that, "Torton lives a little in fantasy." She also told me, "You can't believe what he tells you." Maybe, but I'd like to think that all his stories, the ones he writes down and the ones he talks about, are true. Then again, I guess it doesn't really matter.

HEAVY METAL: The first question I want to ask you is something I've been thinking about since I read Champakou. Do you think there is any possibility that something like that could have really happened?

Jeronaton: I don't know. It's possible, but I'm not sure. It's true that they discovered some form of electricity 3,000 years ago, and they put up so many monuments that we couldn't even build today, but it's not that simple. For example, at San Maya there are designs and people might say, "Look, it's a man in a rocket; how did the Mayas know about that?" But it's only because they can't read the hieroglyphics. Someone who really knows the Mayan symbols would know that it's a mask of Lalac, the God of Rain. So it's not evident.

HM: So you don't "believe" in Champakou?

Jeronaton: I don't believe in anything absolutely. I believe only in life absolutely.

HM: But not in the life of this society. You're always looking for other ways to live.

Jeronaton: Because I'm not satisfied with this life. But I don't believe in many things.

HM: Do you believe in God?

Jeronaton: I believe in some sort of God, or better yet, I believe the world has a reason for being - it didn't make itself. The world is an experiment, but an experiment for whom and for what... I'm not sure.

HM: How did you become interested in the Mayan culture?

Jeronaton: I read a lot about it when I was little. It always fascinated me, and now I've just been in the center of India - where few people go, because you have to travel through dangerous forests to get there (there are tigers and other ferocious animals). I'd like to go back and spend more time there. They live the way they've been living for thousands of years.

HM: And they welcomed you there?

Jeronaton: Yes, because, for example, I read before I went there that the Indians never carry guns into the forest and disdain the white men who go through the forest carrying a lot of weapons. So I didn't carry anything, and when they saw that, they respected me and welcomed me.

HM: How did you start drawing?

Jeronaton: I've always drawn. At school I did nothing except make little designs and comic strips. Then I got sick of school and quit at seventeen. I was very lucky. We were talking about fate before, and I'll tell you what happened that makes me believe in it sometimes. I was going to show my comic strips to the magazine Tintin in Brussels, but I got lost and knocked on the door of the apartment that turned out to be that of Herge, the artist who draws the Tintin comic strip. Just luck, like that, because Brussels is a big city, you know. I started drawing at his house, he corrected some of the things I was doing, and I then published my first strip.

HM: What kind of strips did you draw at first?

Jeronaton: I was doing historical comic strips for children, but it began to get very boring after a while.

HM: And that's how you started drawing science fiction?

Jeronaton: No, at first I didn't know what to do. Then I decided to illustrate the Bible. In the Bible there is everything, and yet no one would be shocked. I worked on the illustrations for four years and it's yet to be published. It will come out sooner or later in ten volumes. When I finished that I made a list of everything I wanted to draw - nature, the Mayas, etc. and I made up the story of Champakou.

HM: How much of Champakou is real?

Jeronaton: The buildings, the clothes, the way they live and speak are all based on reality. In books I've read about their culture, but the rest is a dream. But you know reality goes further than fiction - it's often stranger.

HM: What has happened in your life that was stranger than what you've imagined?

Jeronaton: Ha, that's too personal.

HM: Have you ever had an adventure while you were traveling that was almost "science fiction"?

Jeronaton: No. I've had experiences that were passionate and dangerous but nothing that was almost science fiction. There are extraordinary things that have happened to me, but I can't tell everybody.

HM: You don't think that creating is opening yourself up to the public?

Jeronaton: Of course. You reveal your dreams, your frustrations, your ghosts, and your desires. You always create things you're concerned about. But there are things so personal that I don't tell people because it wouldn't interest them. For example, the Marquis de Sade told all his fantasies, but it's only people like him who can appreciate them.

HM: So what do you want to do for your readers?

Jeronaton: I'm not really sure. Comic strips are like television or the radio: they're not really worth anything. When I used to do historical strips there was always a moral for the reader. For example, I did a story about Spartacus, who organized the slave rebellion, and I wanted to show how he was a good man. But it began to be difficult because people want everything in simplistic terms. They want the good people to be on one side and the bad to be on the other, but everyone is a mixture of good and bad. It's hard to have nuances; people don't want to complicate their lives.

HM: Have you ever had a "'close encounter of the third kind"?

Jeronaton: No, if I had, I'd know a lot more [laughter]. As it is, I hardly know anything.

HM: What about seeing a UFO?

Jeronaton: Well, one time someone told me about a UFO that was seen in the south of France. It had been photographed, and pictures even appeared in some newspapers. The following year I went camping there with my children and some friends, and the same day, the following year, we saw the UFO that was spotted the year before. We returned the following year, the same day, but we didn't see anything. Have you ever?

HM: Now you're interviewing me?

Jeronaton: Yes.

HM: Well, one time when I was younger I saw a white light pass by my bedroom window.

Jeronaton: And it couldn't have been an airplane?

HM: No.

Jeronaton: And did you have enough time to see it?

HM: Yes, but I've never been sure as to what it could have been. You know, after reading a story like Champakou, I would think that you would be less pragmatic and believe more in fantasy than you actually do. Your approach is rather scientific.

Jeronaton: The story is a dream, not at all real.

HM: Do you believe in fate?

Jeronaton: Yes, but I think that people can make their own fates. I used to think that nothing happened by chance, but now I'm not sure. I'd like to think we were created to be, or do, something here.

HM: Then you do believe in some kind of force?

Jeronaton: Yes, but I can't even imagine what it is. Ants can't imagine the world of men, so it's absurd to think that we can imagine some force beyond us. Einstein, before he died, said that the more research he did, the more he was sure there was a God and the more he was sure he'd never understand Him. I think it's the same for me.

HM: Do you ever take drugs?

Jeronaton: No, not anymore. I've tried, but now I'm against it. I smoked hash with the people in India every night, but here it's different. People go crazy with it here.

HM: Have you ever done drugs to change the way you draw or dream?

Jeronaton: No. I've never done them to escape reality.

HM: But you left Belgium, and you've said you want to return to India. Don't you think that's escaping reality?

Jeronaton: No. If you are living a sad reality, fortunately, you can change it. Everything you do you merit, or else you pay dearly. People who don't take their lives into their own hands, then blame the government, the society, or other people, they don't do anything for themselves.

HM: How do you think the world will end?

Jeronaton: Either there will be a nuclear war (as the Bible and other religious texts predicted: the world would end in fire), or people will learn to change.

HM: Do you believe in "I think, therefore I am"?

Jeronaton: Yes. I'm conscious, therefore I am.

HM: Do you think there's life on other planets?

Jeronaton: It's more absurd to think there's no life on other planets.

HM: What do you plan to do in the future?

Jeronaton: I'd like to do something in the Egyptian epoch, not historic, but fantastic. I like traveling to different places and then doing stories about those civilizations.

HM: One final question: What is the most important thing for you in your life?

Jeronaton: That's easy. To be happy.