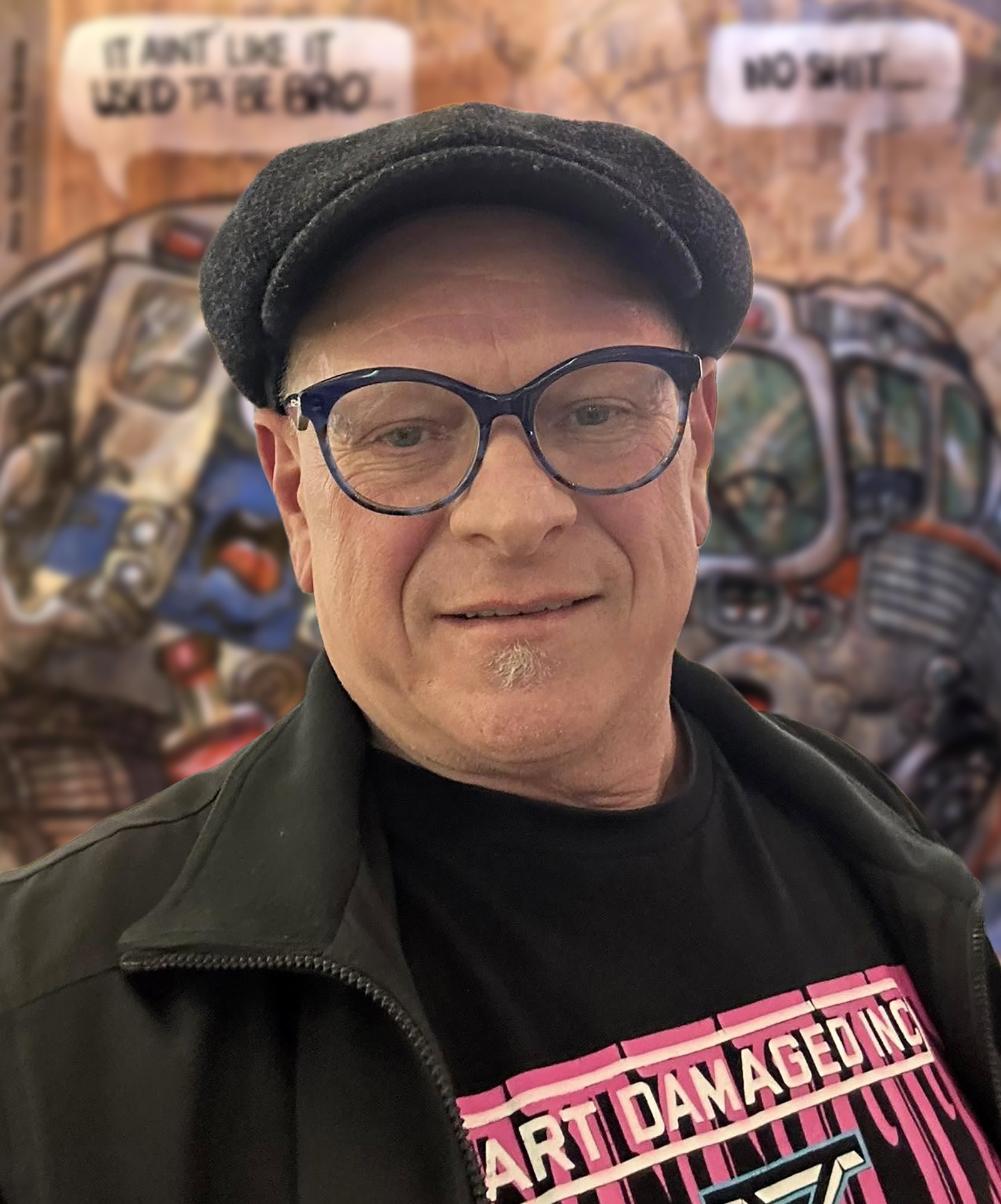

MARK BODĒ Interview

An Interview with Mark Bodē by David Erwin

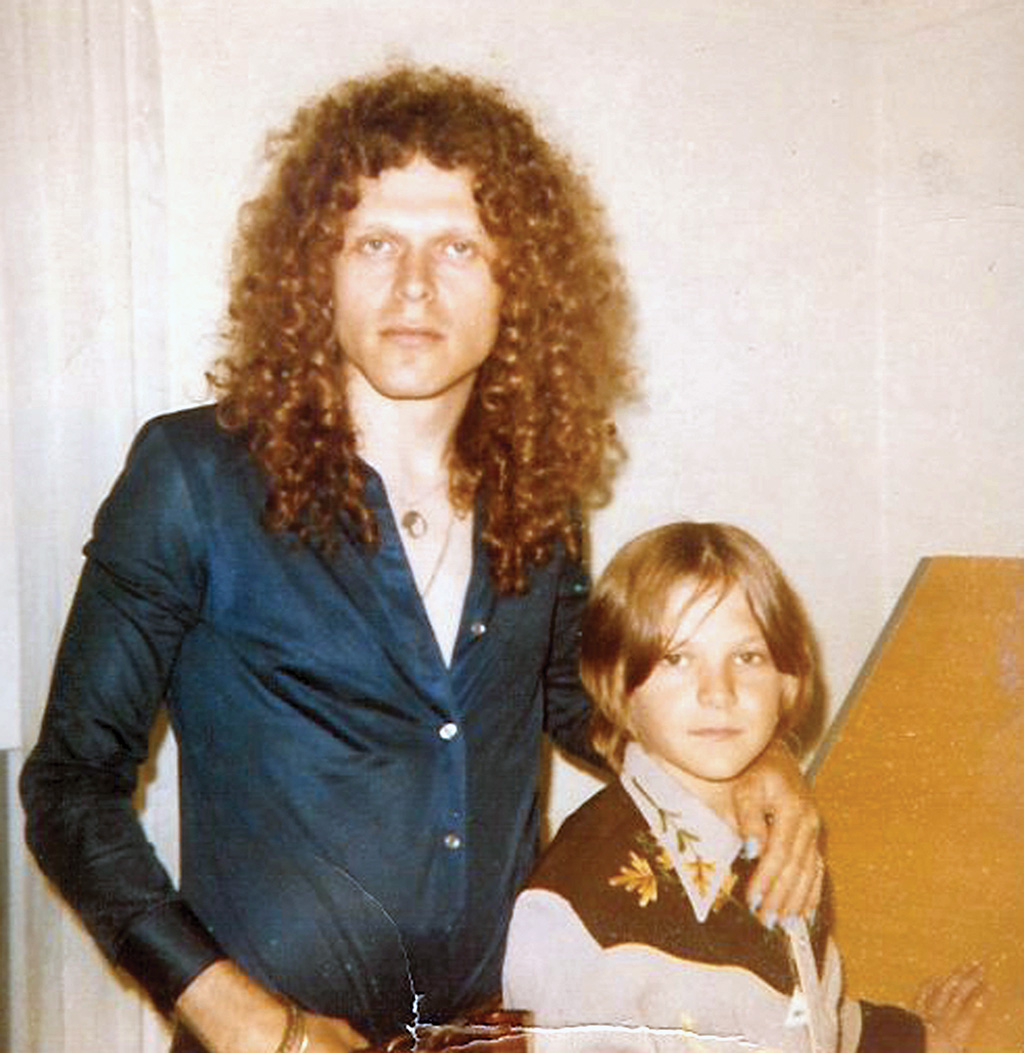

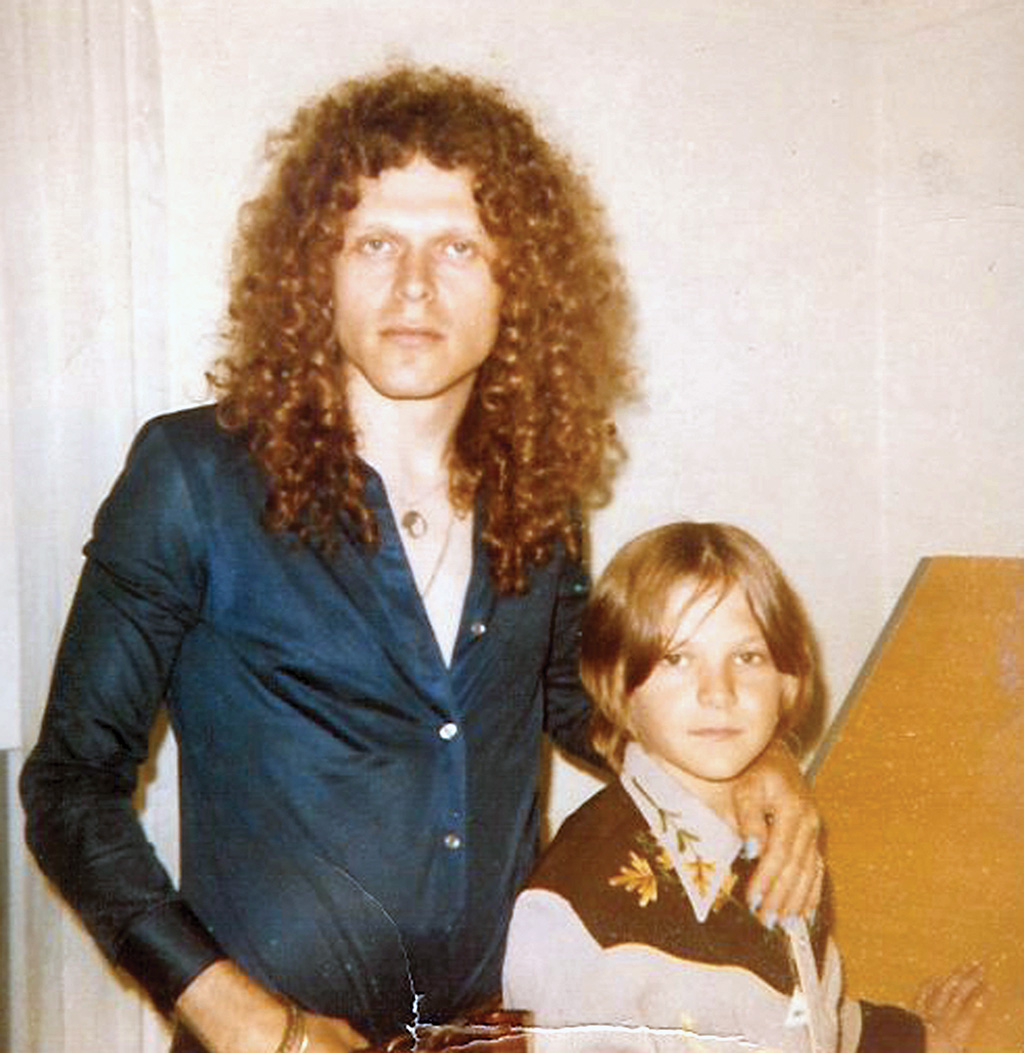

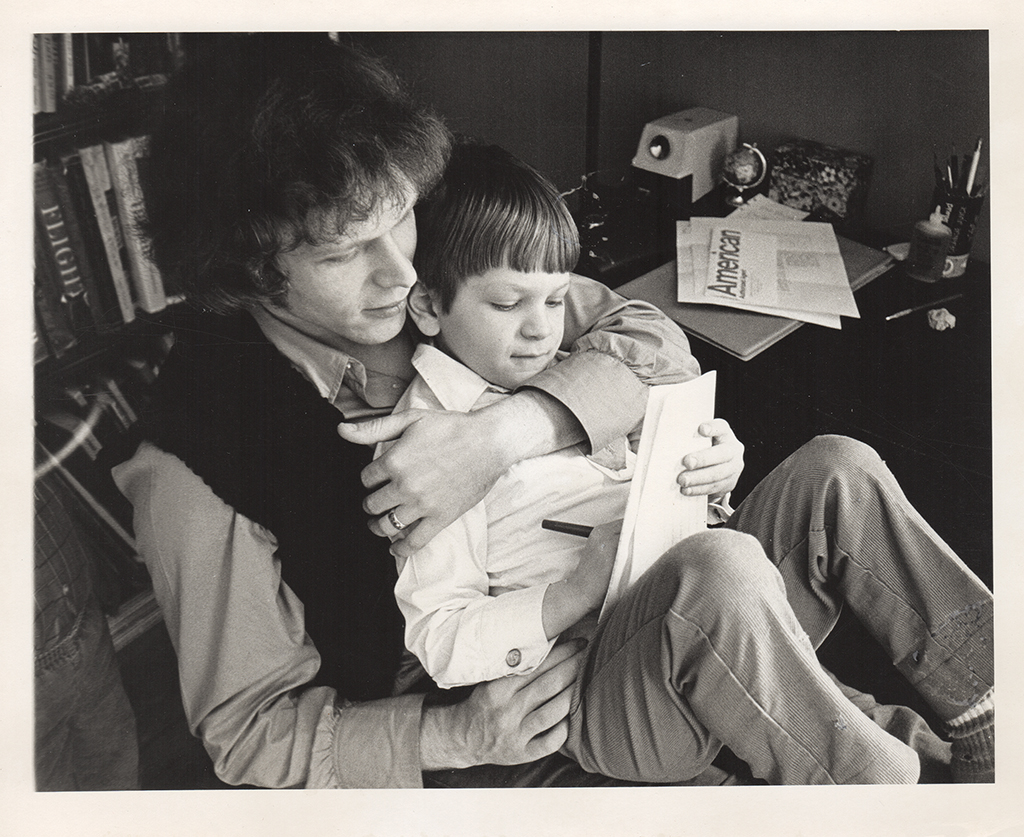

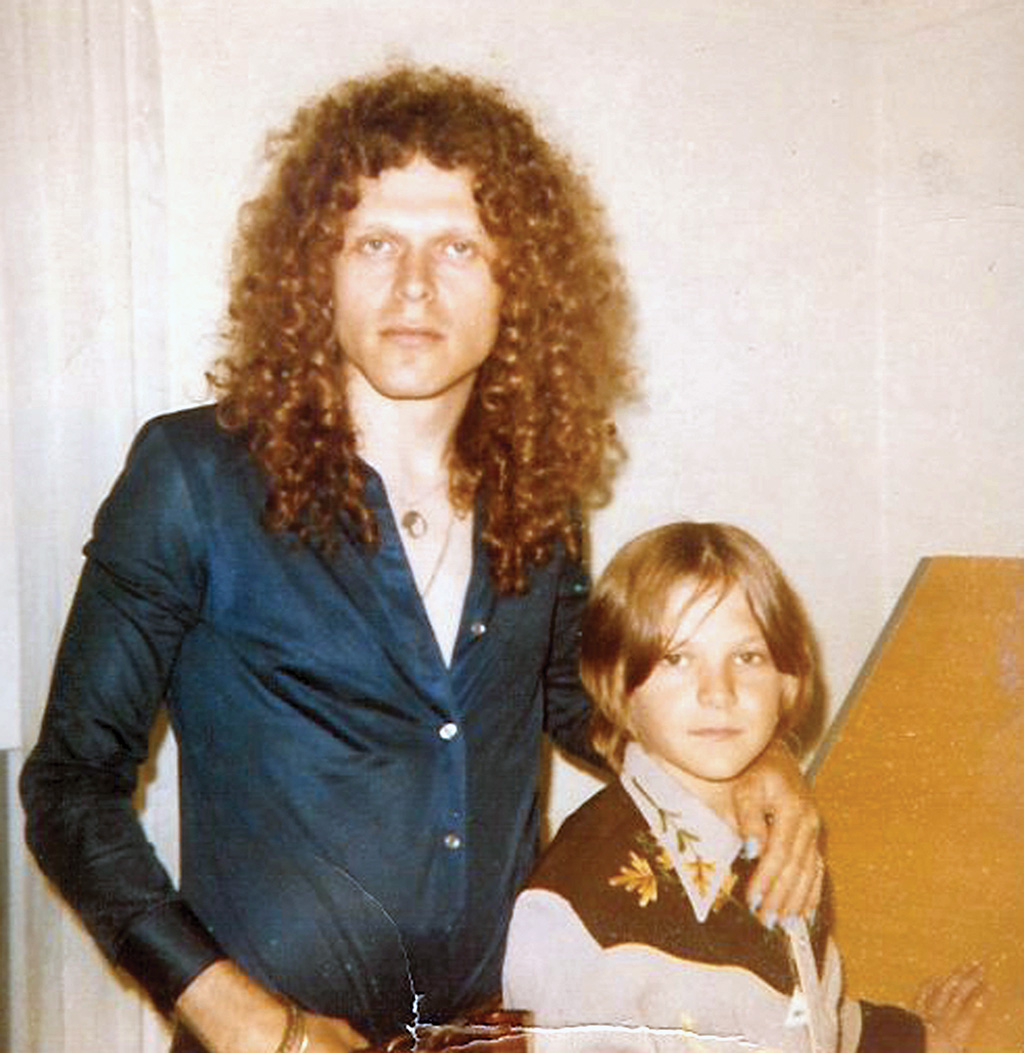

As a young boy, Mark grew up surrounded by a world of imaginary characters and places created and told to him by his father, Vaughn Bodē. As the son of a legendary artist whose influence has touched everything from cartoons to graffiti, Mark shares his memories in finding is own path, while carrying the responsibility of his father’s creations and art over the decades after his untimely death.

HEAVY METAL: You’ve been drawing since you were 3-years-old and published in Heavy Metal by the time you reached 15. Recently, you returned to Heavy Metal with new works. How do you feel about your return in Heavy Metal’s milestone issue #300?

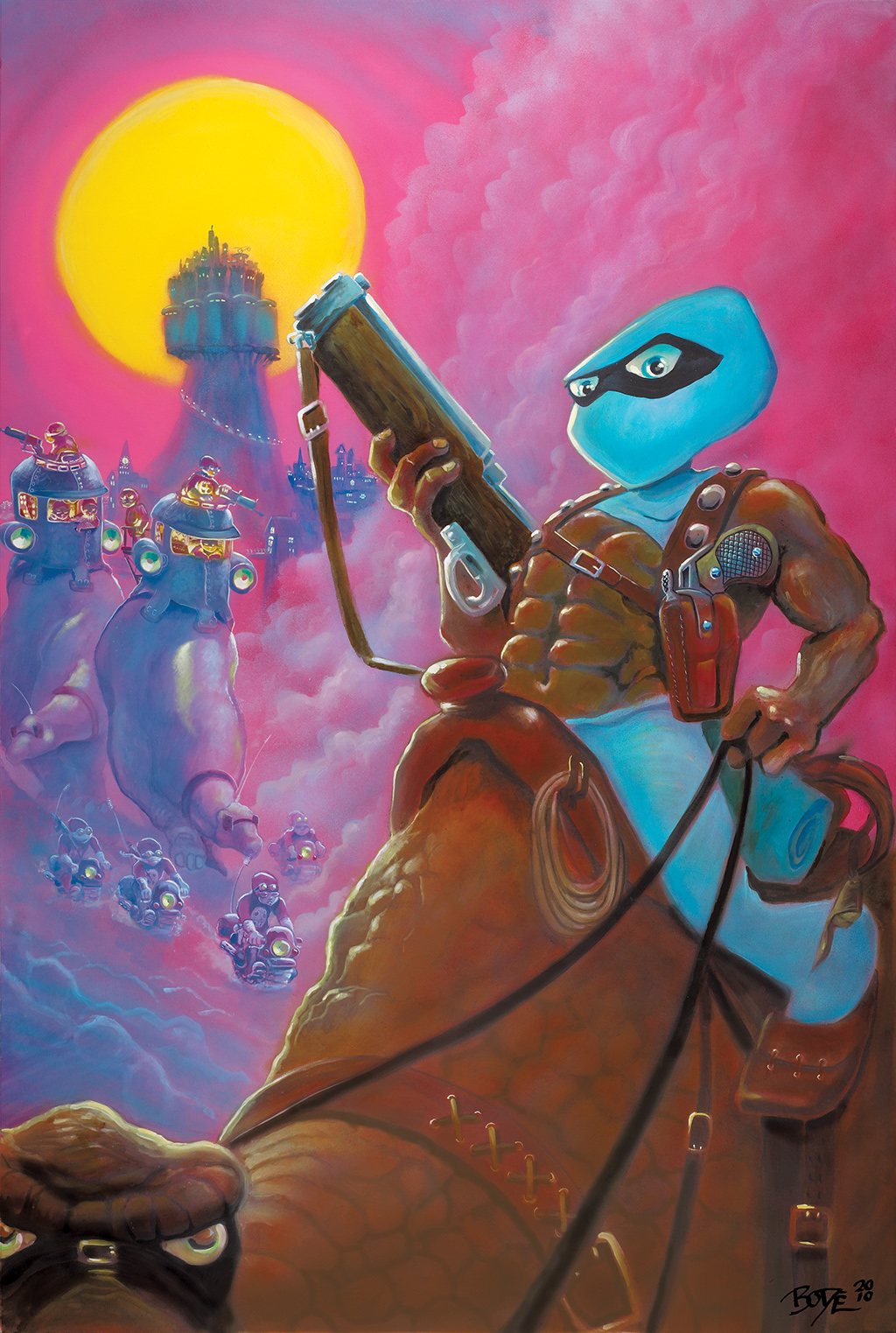

MARK BODĒ: Dave, it’s an honor, it really is. So much has gone on and I’ve gone all over the world with our characters, comic cons, and art shows, mural events, movie premieres and during it all Heavy Metal was there and it’s amazing to be back in the saddle spinning some new stories for new followers in issue 300. It is the greatest American Science Fiction Fantasy Magazine of all time and I’m damn proud to be in it once again.

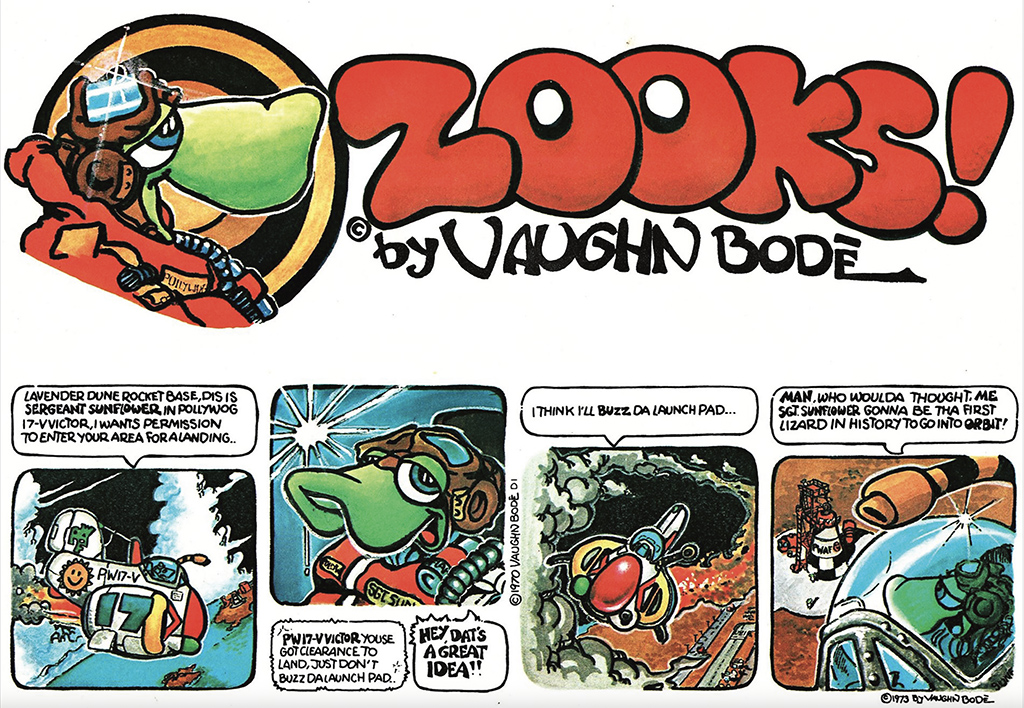

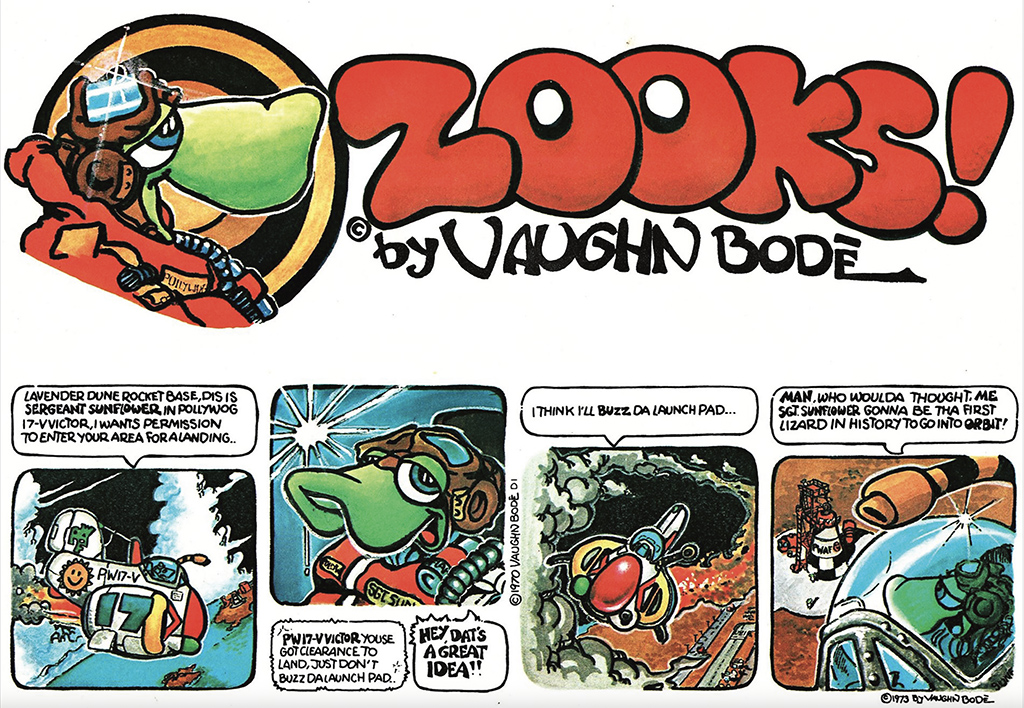

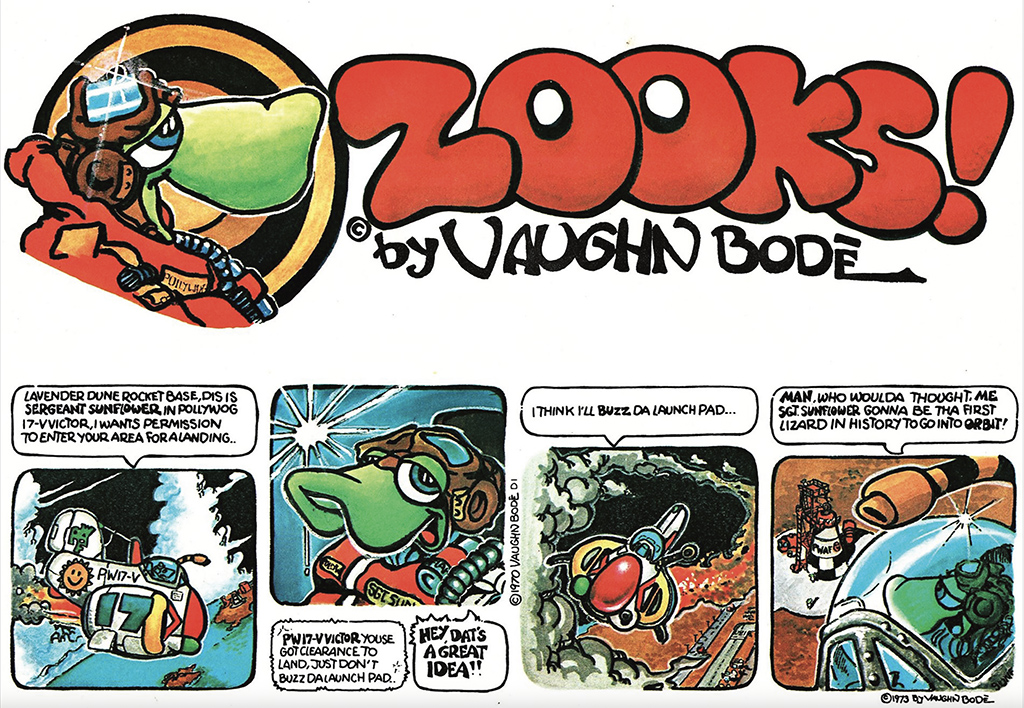

HM: Your first project for Heavy Metal was coloring your father, Vaughn’s, unfinished work "Zooks, the First Lizard in Orbit" – you were 15 years old at the time. How did this come about?

MB: Well, in 1978 I was attending The Art School in Oakland California. I was in 10th grade and wasn’t the best student to my teachers. I grew up around the best illustrators and painters in comics and pop culture. I must admit, I knew it and acted pretty cocky, as teens tend to do. People like Jeffery Catherine Jones, Bernie Wrightson, and Larry Todd - to name a few - were my uncles. There seemed nothing these art teachers could teach me that I did not know already. When at the time, Editor-in-Chief of Heavy Metal, Matty Simmons, asked if we had more Vaughn Bodē art for the magazine. My mother, Barbara, answered, "Yes, we have some black-and-white strips." Matty wanted colored art. It was then that Larry Todd, who had taken over mentoring my apprenticeship in art, suggested, "You color it, Mark." I was sure the project would get turned down if we pitched the idea. Vaughn’s 15-year-old son was to finish his father's work? So, it was decided I would ghost the project with Larry teaching me some tricks as I go. It worked and was printed a few months later. When I look now on those pages, they hold up very well. I can say, "Good job, kiddo" to my much younger self. That job and getting paid for it really gave me the confidence to follow in my fathers’ footsteps and to go pro and not look back. I must be still the youngest to work for HM. If there is another let me know.

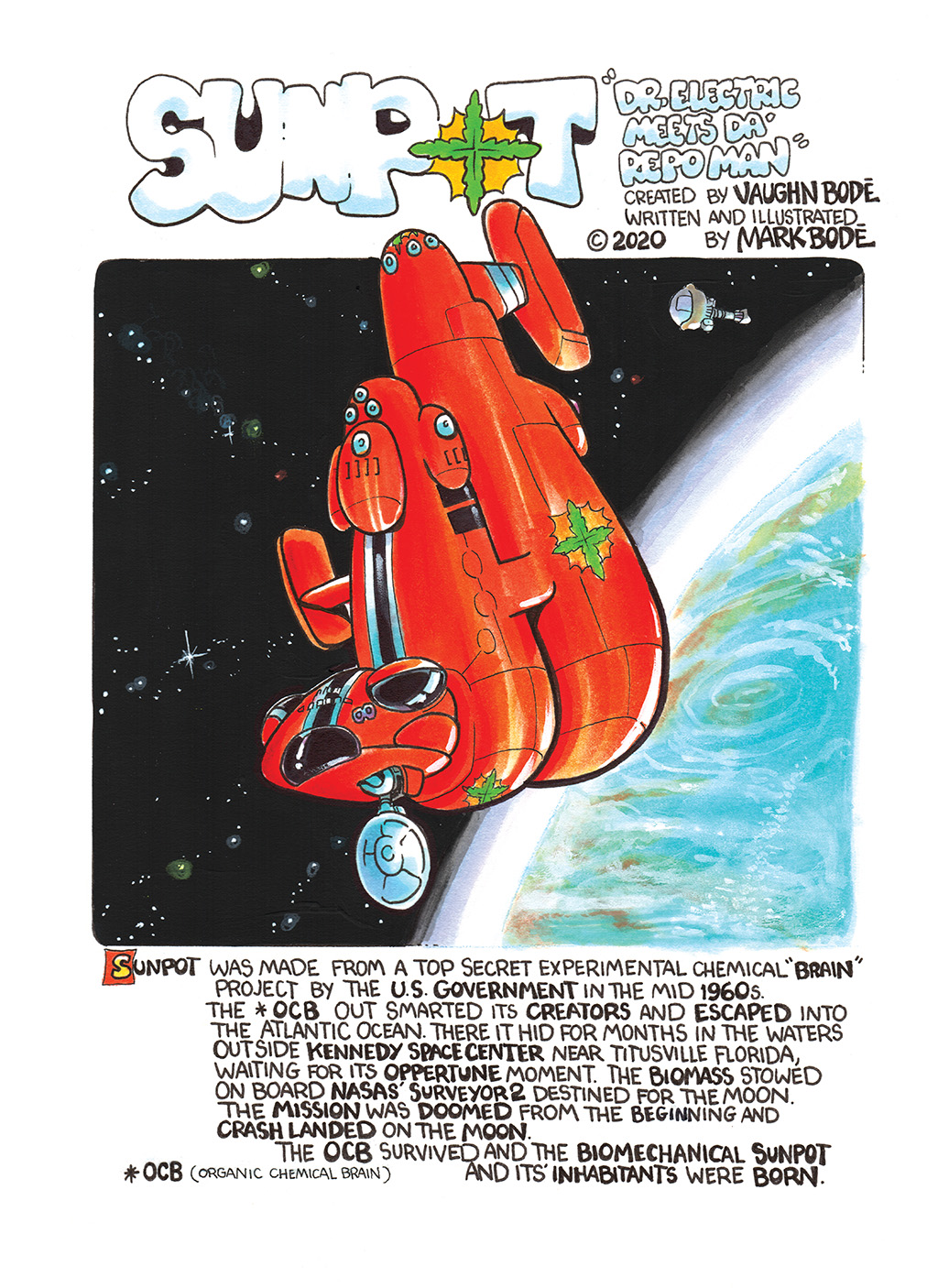

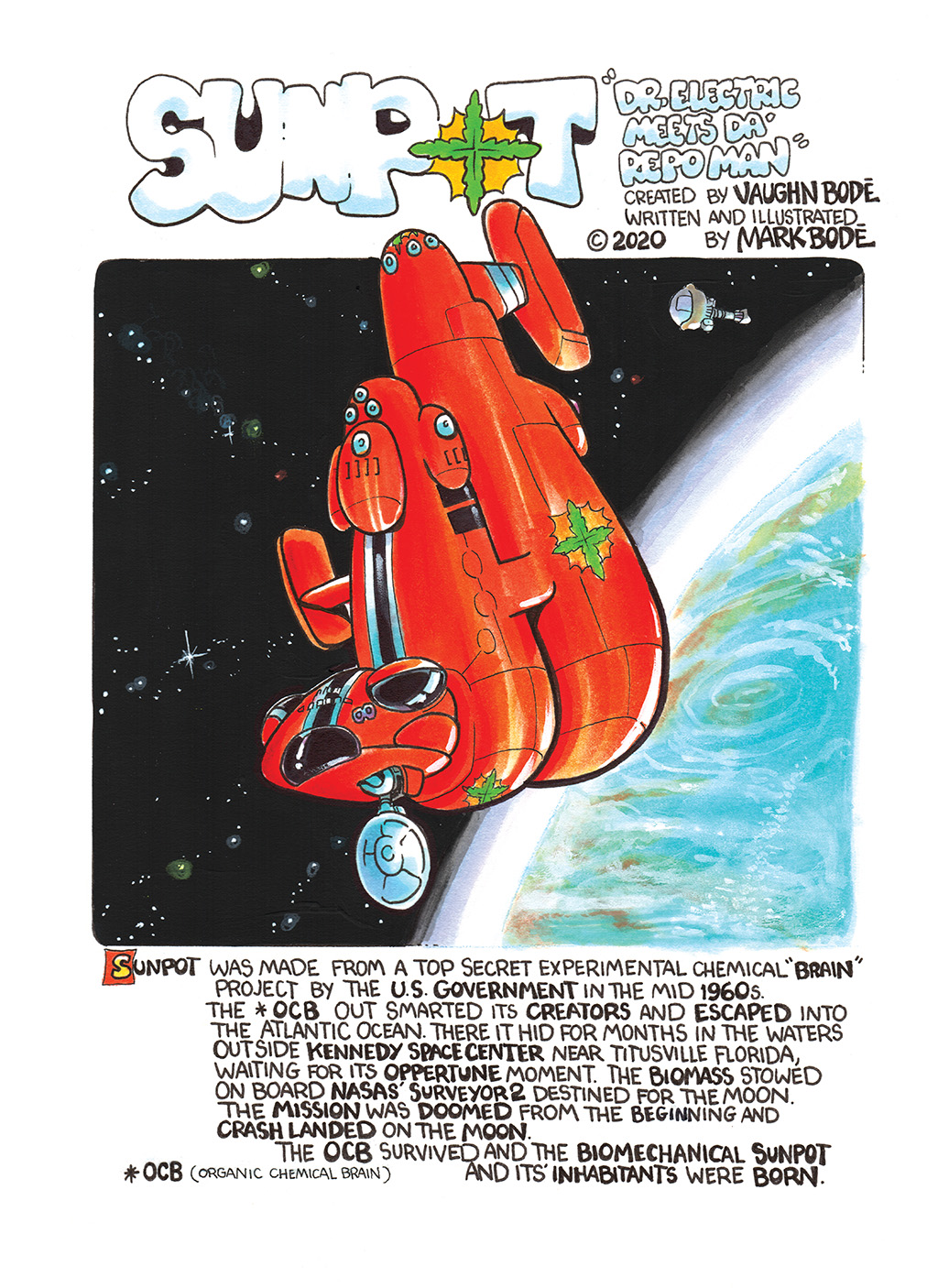

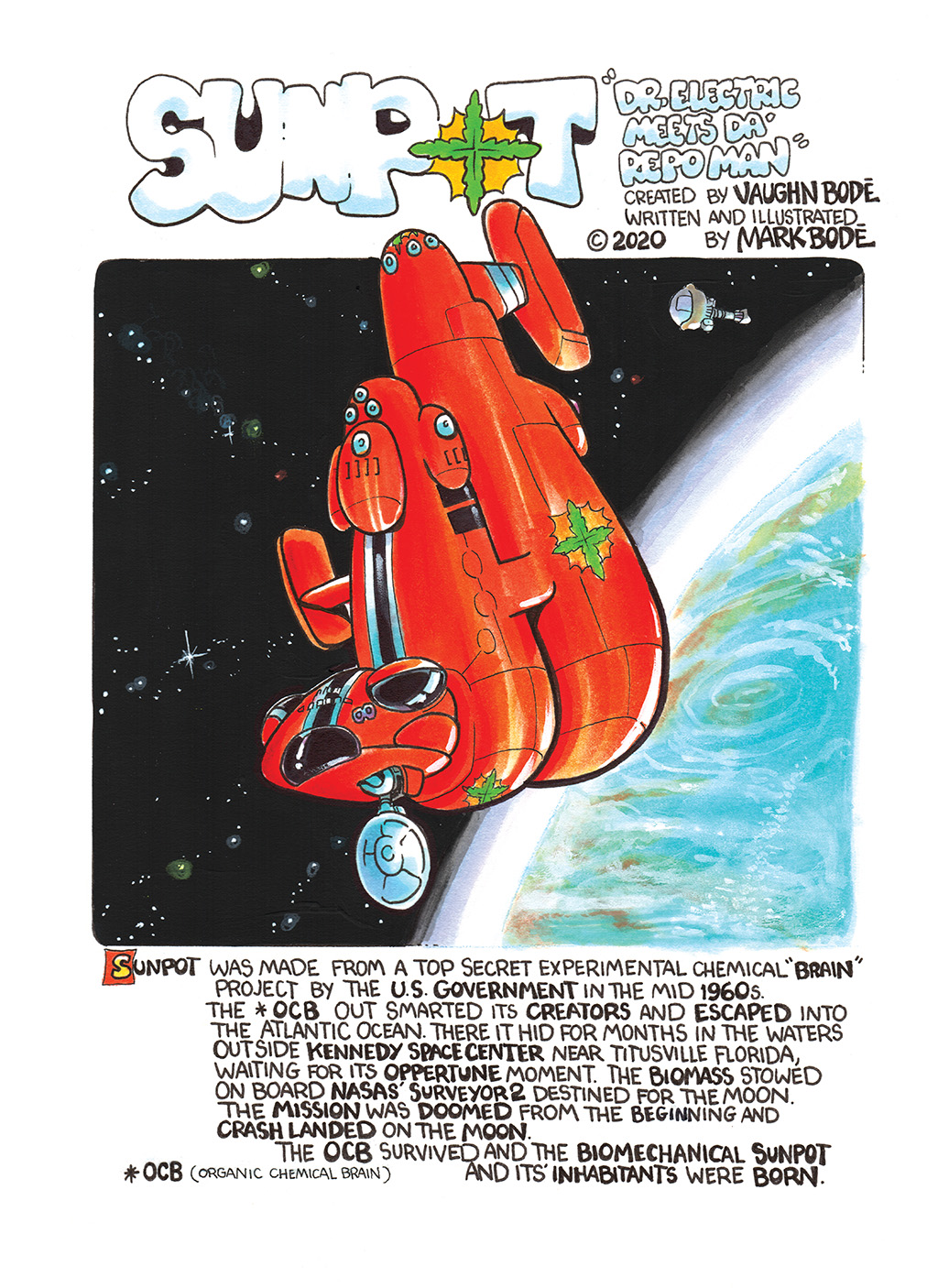

HM: For #300 you’ve completed and added additional pages to his unfinished "SUNPOT, Dr. Electric Meets Da’ Repro Man" story. How did you come to choose Sunpot over other properties?

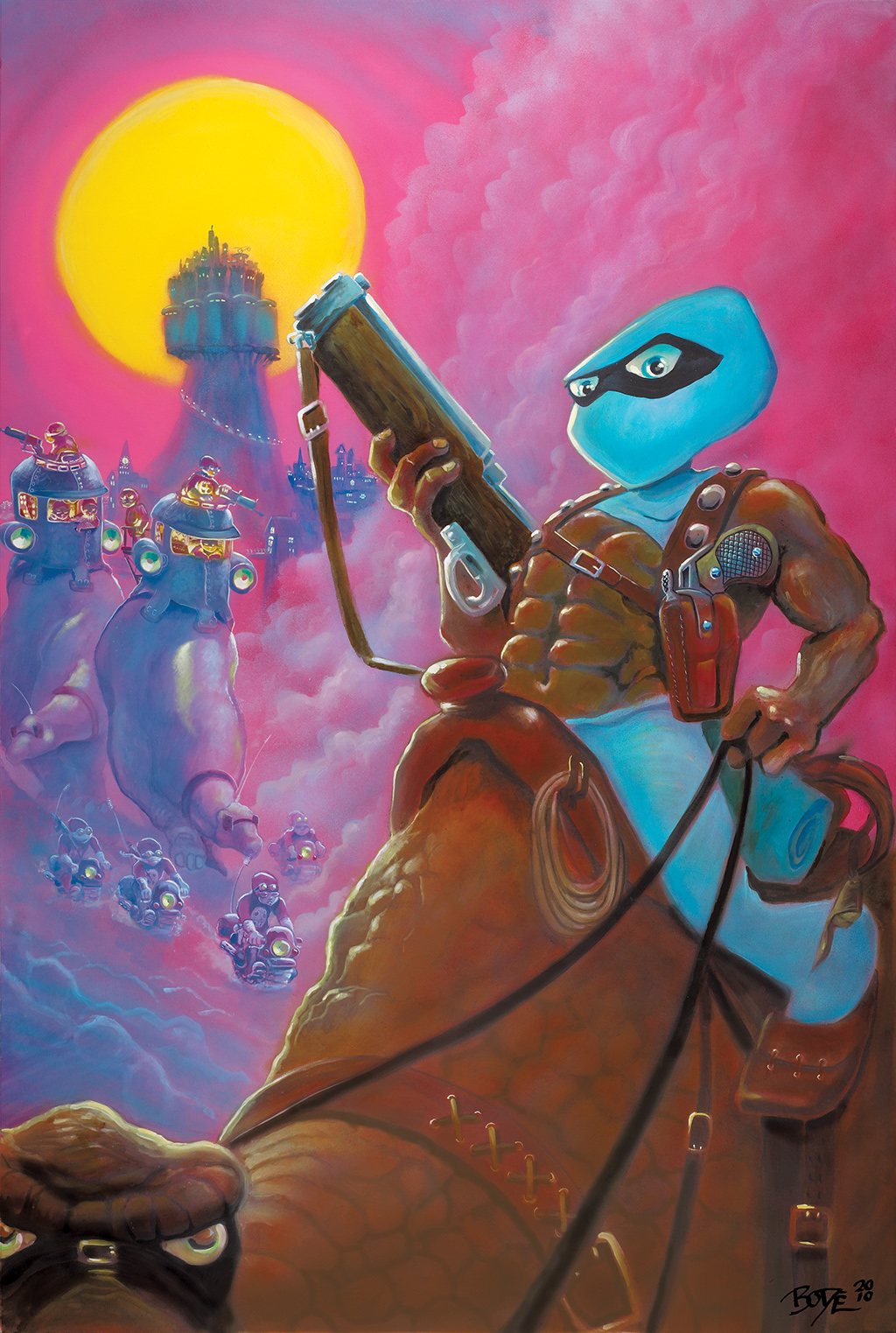

MB: Well, now that it's hundreds of issues later and I'm in my 50s, I can still find excitement to work and spin some new stories. When I was a teen, there were three properties that Larry Todd said I should expand on. The first being Cobalt 60. Larry suggested this first because Science Fiction is the wave of the future and Vaughn did not expand enough on that world, which is our radioactive future on Earth. Vaughn only did 20 pages of story and art for this property and suggested a cast of unused characters for a longer story that never panned out, 'til Larry and I turned it into a 500+ page epic. Second was Sunpot. Sunpot was an erotic sarcastic take on life in a chaotic and insane organic spaceship. Vaughn did a 30-page story broken up into chapters that ran in the pulp Sci Fi magazine Galaxy in the early '70s. My father wanted a better page rate from the editors and was turned down, even after the strip had increased the magazine's print run. So, Vaughn turned in his final installment, "SUNPOT is DEAD," where the entire crew hits a toxic gas cloud and dies. The magazine editors were speechless and the magazine tanked a few issues after Vaughn terminated working for them. The third property is Cheech Wizard, but I agreed with Larry that Cheech was too personal to Vaughn. I mean, Vaughn is Cheech Wizard, he is who is under the hat. So we should not continue that property... at least not for now.

HM: What was that like for you to revisit your father's characters after all these years?

MB: So, for 40 years I have been secretly yearning to expand on Sunpot. It has always been on a backburner wanting to come forth. When you and the staff approached me about some unpublished Vaughn work that could grace issue 300, I had a hard time finding stuff that was finished because Vaughn was always about getting in print. I was pawing through old college material of my Dad’s that was cool, but didn’t have the HM edge. I had a eureka moment, like Dad tapped me on the shoulder and whispered, "SUNPOT!!!" So, I dove into drawing up a short story and doing some pencils and here we are! Like old friends come back from the dead to get into trouble again. These characters are under my skin and all I gotta do is give them energy and they kind of start talking and threading their own stories. It has been pure joy and a way to spread the world of Bodē to a new group of readers.

HM: Your father left behind a huge universe of characters and worlds, just how big is that universe?

MB: Oh, unbelievably deep. I keep trying to organize it, I keep trying to delve into it every decade or so. A lot of it were drawn on whatever was around the house, garbage bags, laundry bags. Whatever he had, he would draw on. I would say thousands and thousands of characters are sitting there and could be added to or updated. His most prolific time, I would say was between 1958 and 1962, where he created thousands of worlds and characters, almost on a daily basis. He wouldn’t just doodle some character, he would create moons and planets and name them all. Then go into the planet and populate it with cities, towns, rivers, streams and name them. Then populate them with characters and let their stories unfold from there.

I don’t know how he did it. I know he ate a lot of Hostess Snowballs and Twinkies and coffee... a lot of coffee. And zoom around all our heads as if we were sitting still back in the caveman days. I mean, he was zooming and stay up for two days at a time just on the junk food and coffee.

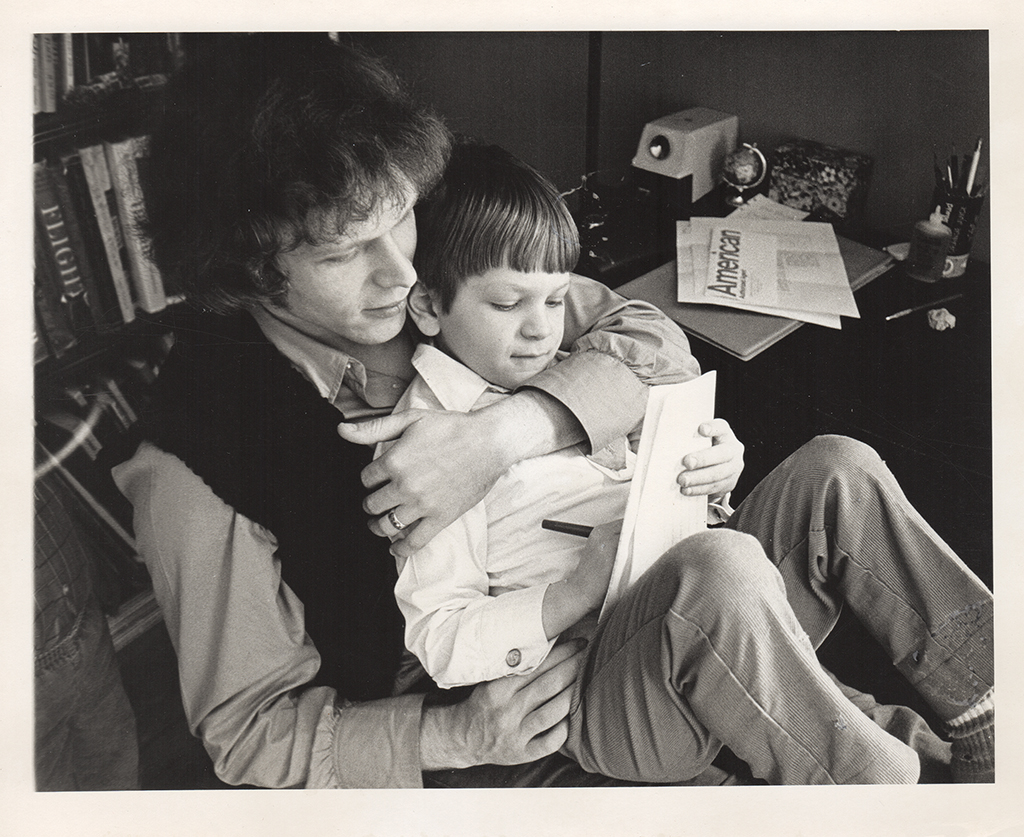

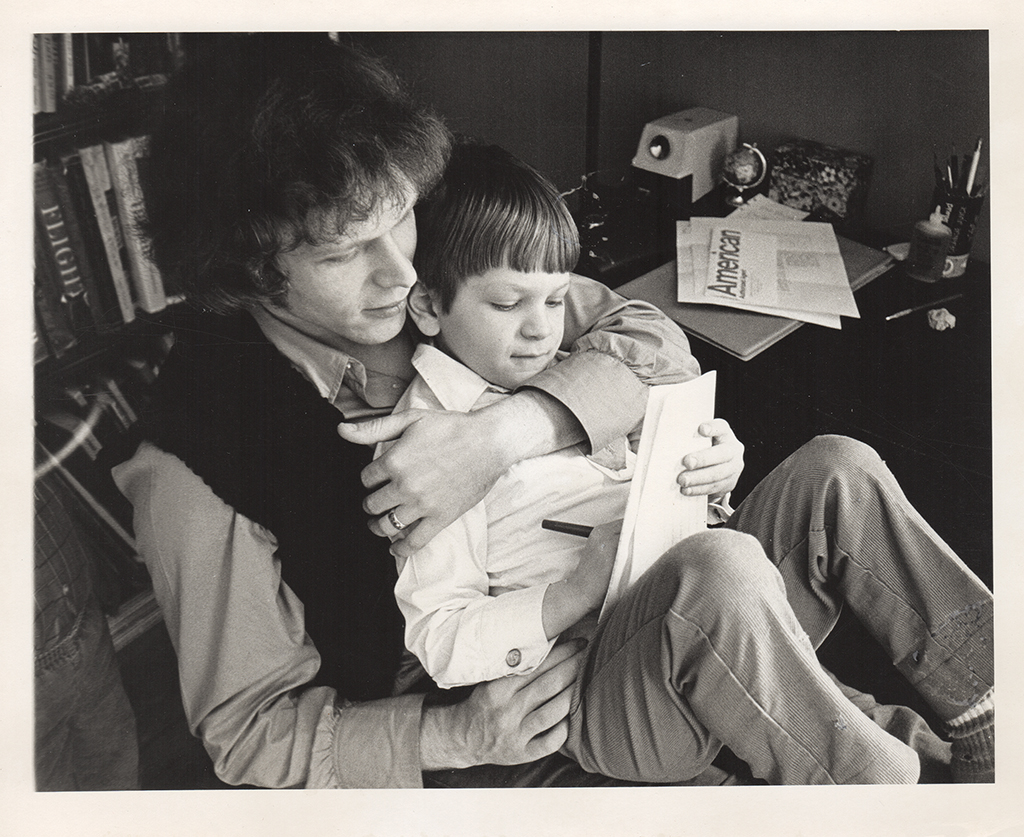

HM: Did your father tell you stories with his characters?

MB: My childhood was filled with stories. I know at times Dad was testing new ideas on me at bedtime. The bear went over the mountain not to see what he could see, but to visit his pal Cheech. I looked forward to those stories. They had a basic structure that always went off in a bizarre and fantastical way by the time, "Good night, Mark" and the kiss on the head came. Every night my head was full.

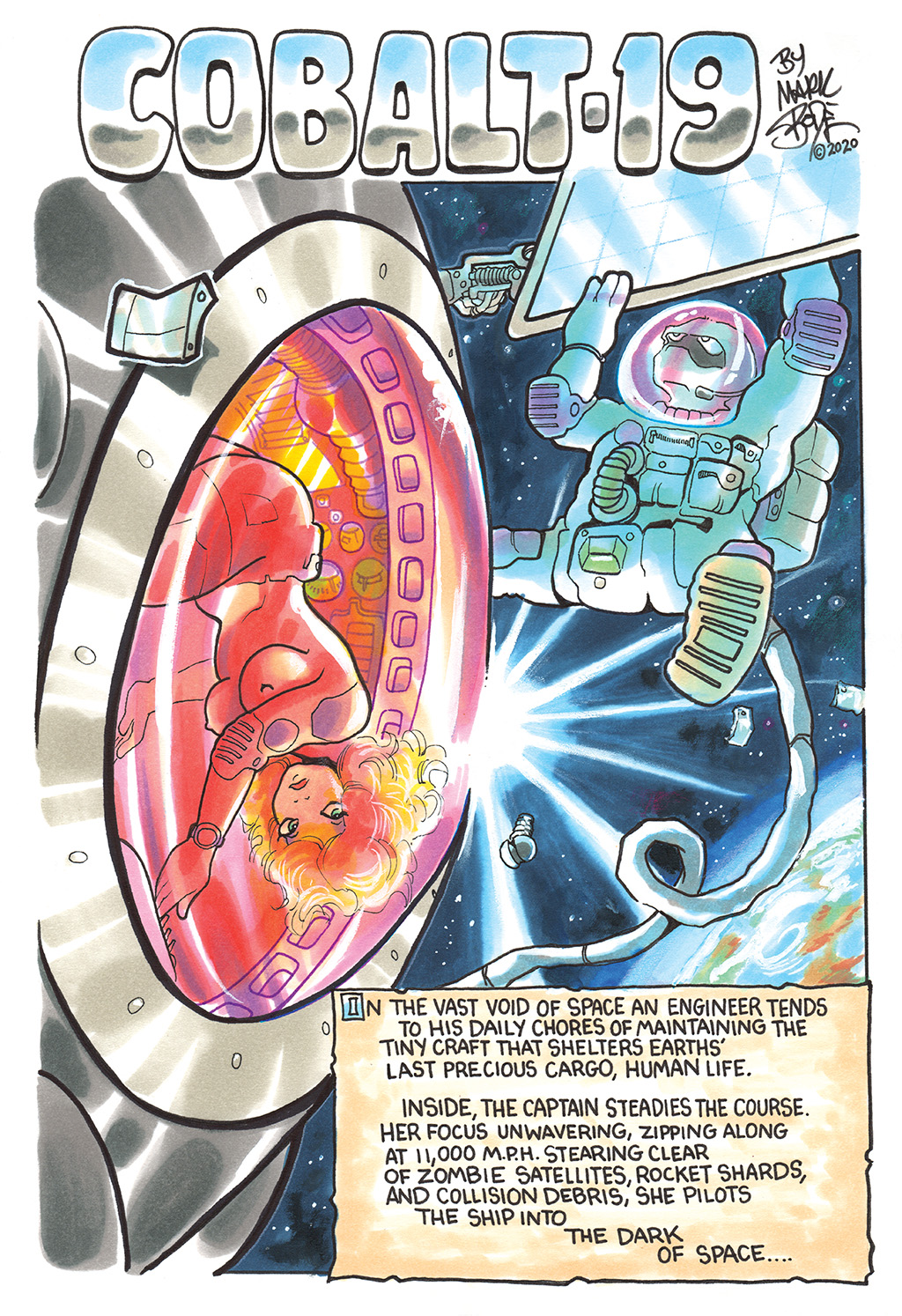

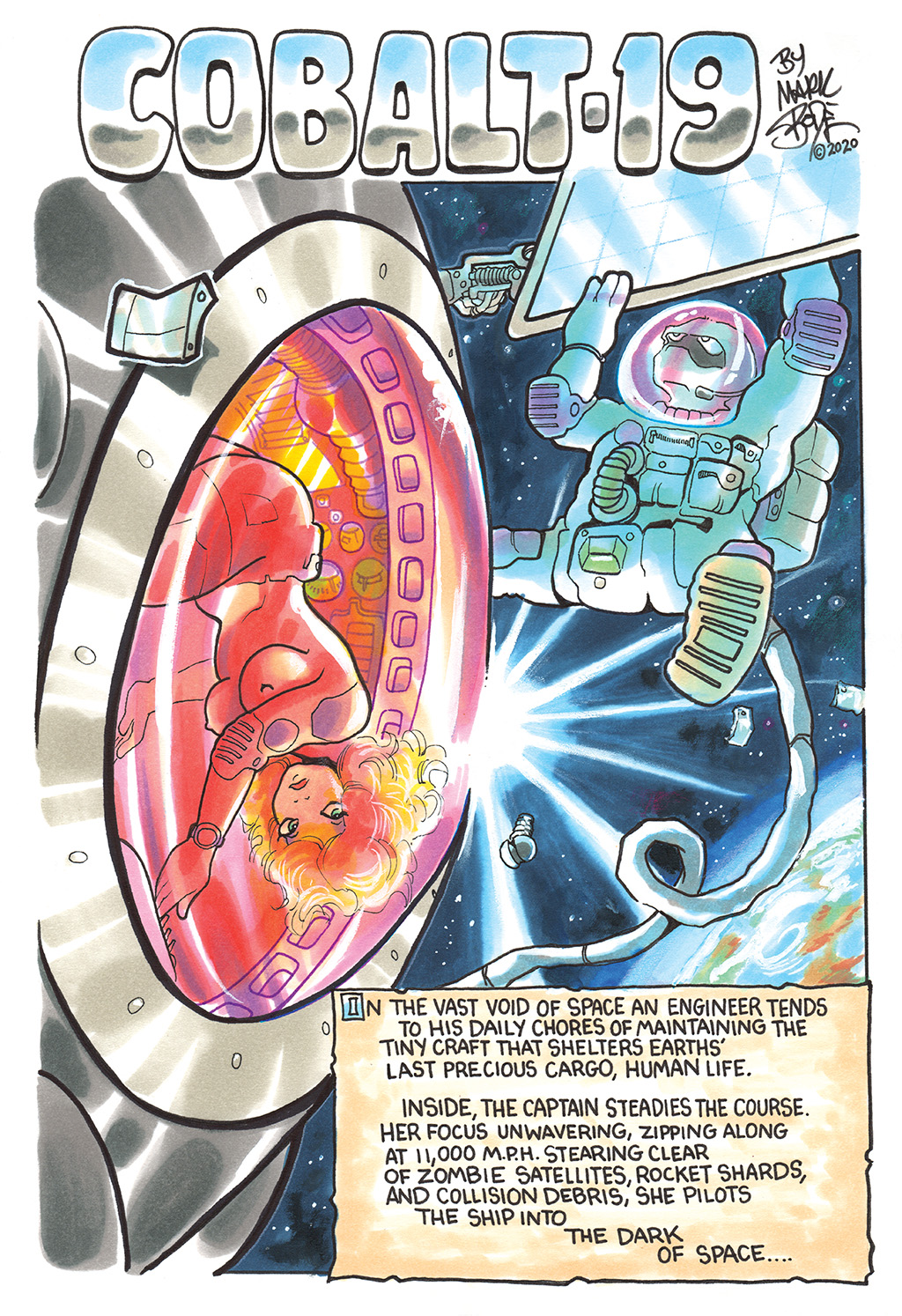

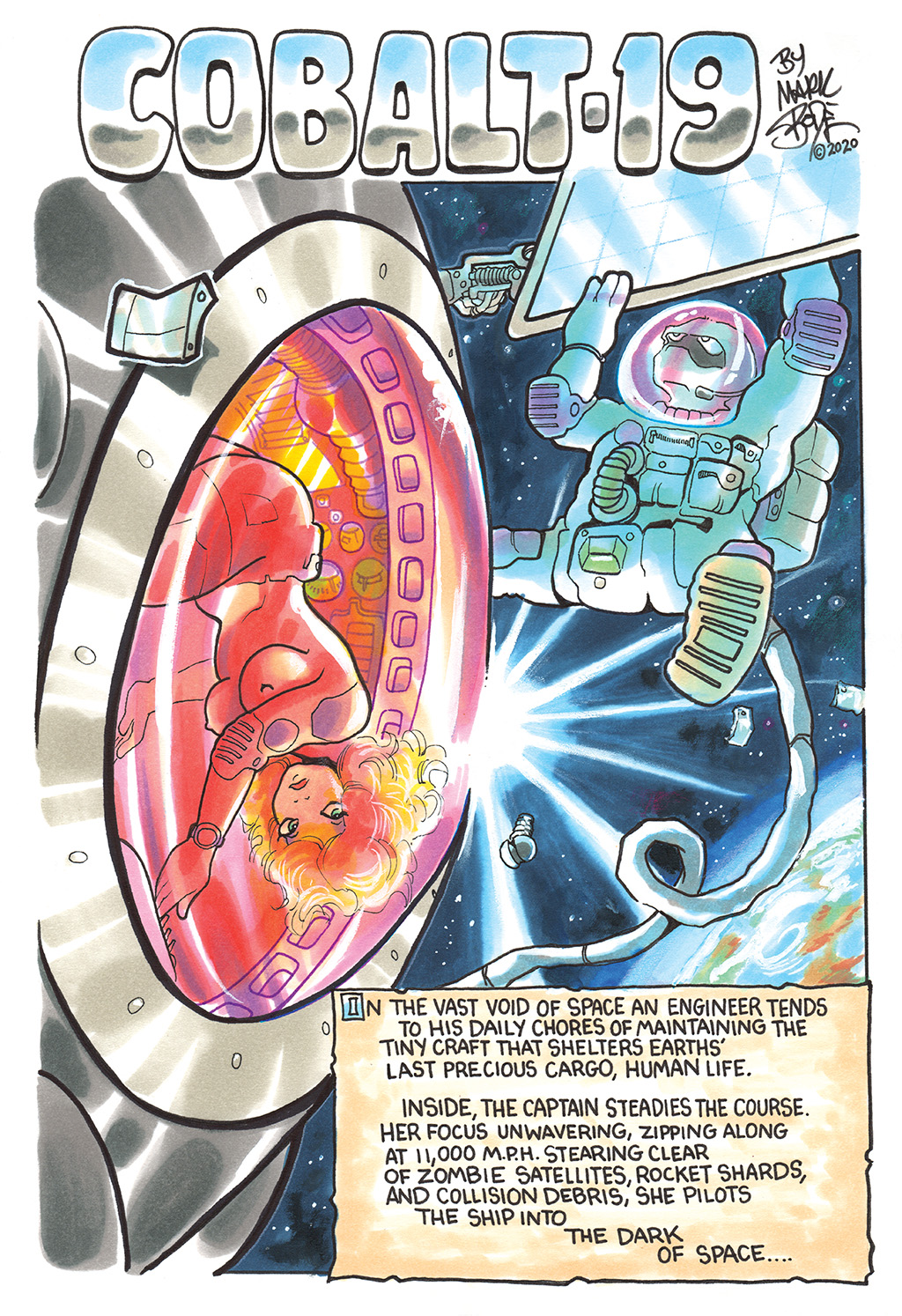

HM: On the subject of revisiting your father’s characters, you’ve also written and illustrated a new short story based on Cobolt-60 that will be featured in Heavy Metal #302. What inspiration for this?

MB: Well, that was a bit of a departure from Cobalt’s normal world. As I was taught, "Don’t draw what you have to draw, always draw what you want to draw." I stared at the empty page and wanted to draw a zero-gravity sex scene with a Barbarella flair. "How’s that work?" I thought, "Hmmm, maybe I should get out some of my fears of this Covid anxiety my wife and family are experiencing." A dark, Covid-19-inspired short story unfolded. It’s a bit of a bummer, but hey, I had fun drawing it. Mission accomplished! (laughs)

HM: The first time I’d met you, I was a student at New York’s School of Visual Arts. You were signing your original comic book Miami Mice at a small, eclectic, hole-in-the-wall shop in Soho. Obviously, it’s a take on the television show Miami Vice, but can you tell us what compelled you to enter into the Indy comic book market?

MB: Sohozat! What a great store that was in the village I believe? I remember meeting you there for sure, I was glad somebody showed up! Thanks, Dave! (laughter)

Well, I also meet Henry Chalfant for the first time there, too, and Mare139... him and his brother, Kel, did massive top to bottom cars with Bodē characters in the early '80s into the '90s. Miami Mice was my first full-on comic book, outside of my father's worlds. It was a design I saw on carnival prizes and t-shirts. The Ninja Turtles had just begun selling out comics and hadn’t made it on TV yet. A black-and-white funny animal boom seemed to be taking hold of the comics scene. My wife, Molly, suggested that it would make a great comic book. I did some sketches of what I’d do with the parody and pitched the idea to Fred Todd of Rip Off Press, they did the Freak Brothers underground comic with Gilbert Shelton. They printed it on a whim and in one year’s time we sold 150,000 comics. Here it was my very first solo venture, I thought I had the golden touch. I ended the Mice in issue #4 with a TMNT and Cerebus crossover and went to another more interesting project... that did under a 2000 print run. Live and learn.

I ended up joining Kevin Eastman’s team of artists and we went onto have the time of our lives being on that wave. Yes, comics were very, very, good to me. The Internet changed all that, but damn... it was a hell of a ride!

HM: Would you go back to Miami Mice?

MB: (Laughter) It was bad! I was, "This is so not me." The over-the-top violence, the guns, and then in my studio, I had a mouse problem and mice were running over my feet while drawing it. I started taking my BB-gun and hiding under my drawing table waiting from them to come out of the walls... (laughter) I was, "It’s time to stop, Mark!"

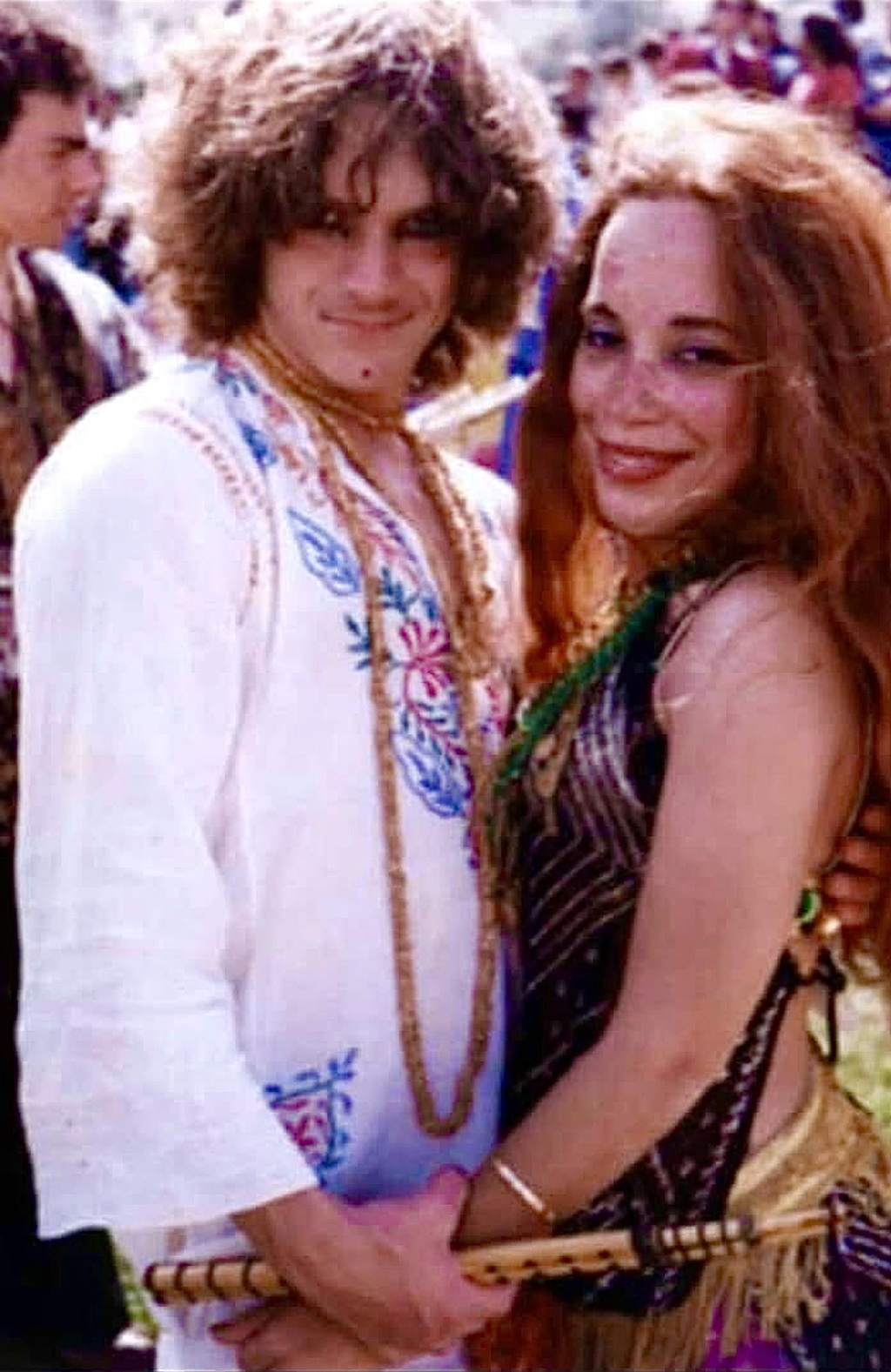

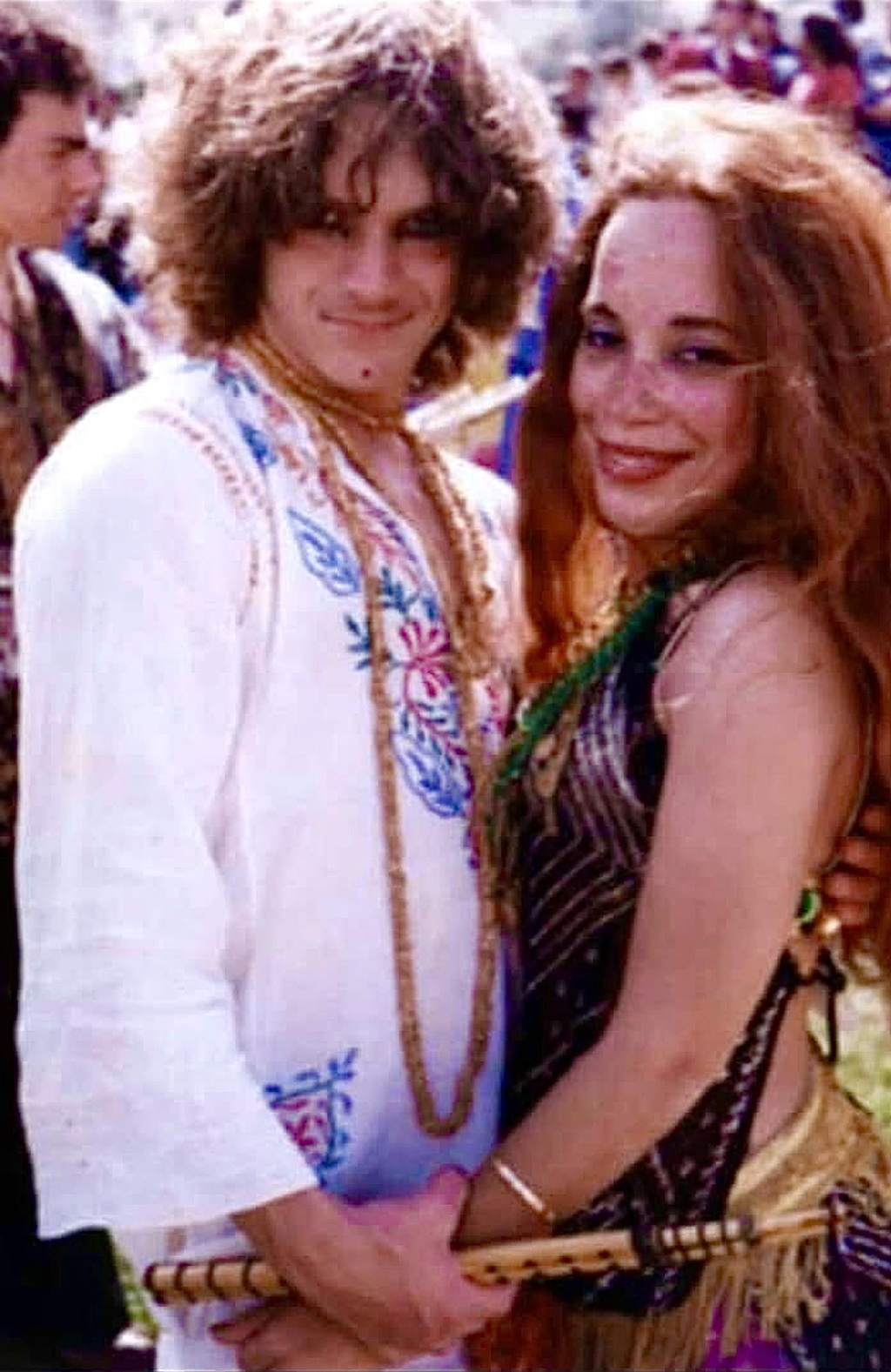

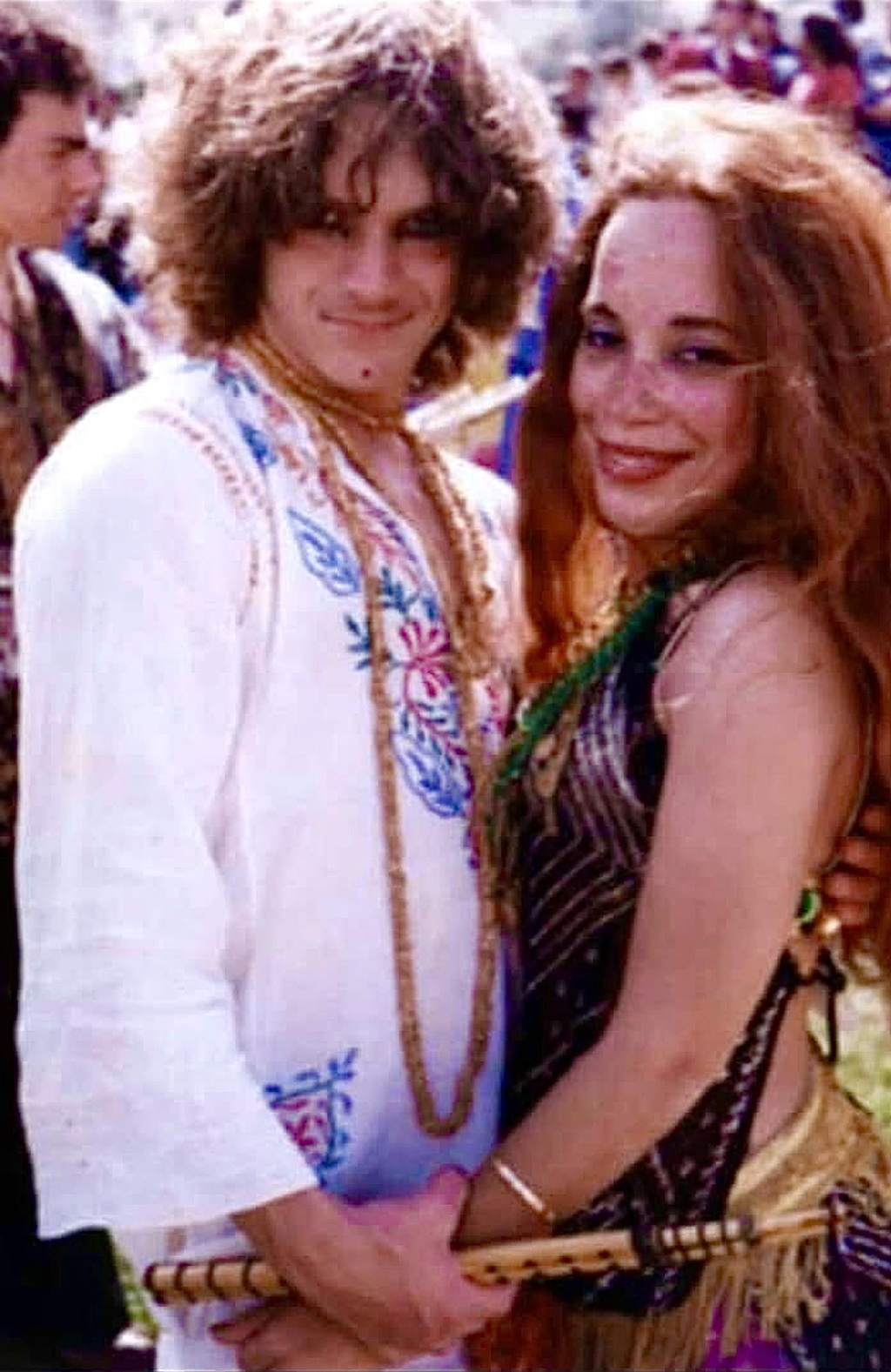

HM: This is a side note, I recall when you were signing, your beautiful wife accompanied you or maybe she was still your girlfriend at the time, looking very much like a Bodē Broad. Has that ever crossed you mind? Tell me a little about Molly.

MB: Yes absolutely. When we met, she was a professional belly dancer. When I saw her dance at the Haight Street Fair in the late '70s, I said, "I must make her mine!" Love, infatuation, lust, the whole deal. I studied Arabic and Moroccan music to accompany her performances for many, many years, mostly on the west coast. She is my muse, my own personal Bodē Broad and I do not need to use models when I draw women... her looks, her hips, her prowess, is engrained into my DNA forever!

Molly also joined the Mirage Studios/Ninja Turtles team as an art-licensing assistant. She has been a huge help when anyone wants to license my images.

HM: I’d recently learned that you were also a student at SVA a few years before me, studying Fine Arts, also the same as me. What was your experience like attending there?

MB: I loved it. I was so honored to be accepted in there. I didn’t... I don’t think I got any scholarship or anything, but I was so excited. And I couldn’t believe Molly, my girlfriend at the time (who is now my wife), she lived in Brooklyn and we lived in San Francisco where we met. And she, out of love, moved back to Brooklyn even though she didn’t want to.

HM: I’m surprised you majored in Fine Arts when SVA has one of the best comic book departments.

MB: Well, I didn’t have a choice being a freshman. You had to take all the basics. And, I really wanted to be in Art Spiegelman’s class. There were certain people I was really looking forward to the next year. But we ended up moving back to San Francisco after two semesters, so I was just there for my basics. And I had Jack Potter. Does that ring a bell?

HM: No, I don’t know him.

MB: Well, he was a Yul-Brynner-type looking guy, and acted more arrogant than Yul Brynner. He would teach life drawing, “Five-minute pose, five-minute pose...” and you’re trying to keep up with his assignments. He’s like, “Change the pose, change the pose!” Then he’d walk around to see what everybody was doing... and he’d stop behind me, and a feeling of doom would happen – it wasn’t a good stop. I’d drawn a Bodē Broad of the woman sitting in the middle of the room. He was, “WHAT IS THAT?! Bubbly, cloudy drawing!” And I’m like, “It’s a Bodē Broad.” He ripped my drawing off the drawing board and tore it up! “DRAW AGAIN! USE YOUR EYES!” and I was, "Oh my God, I’m not going to survive this."

Another time, I was thinking about dropping my name just so I’d do better in the class. But at one point, he said, “One thing I despise are SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF ARTISTS! They’ve got this FIXATED WAY OF DRAWING AND THINKING! I’M GOING TO BREAK THEM DOWN!” Aaaah! I was so traumatized I didn’t say a damn thing after that. But he changed the way I think. He said, “Half of you will go onto BORING CAREERS! Look at me!” And then right outside there was a thunderstorm, “BA-LOOSH!” with lightning, and then he goes, “SEE!” (laughter)

But Spiegelman... I was actually working on "Yellow Hat." I was working for Archie Goodwin, and all my all my classmates were jealous because I was working for a major magazine, which wasn’t surprising because of who my Dad was... I didn’t give myself credit. I showed "Yellow Hat" to Spiegelman because I wanted to take his class and thought he would be like, “Yeah! Following your father, cool, go Mark,” but he didn’t say that, he said, “You got your father down, move on to your own stuff.” Huh? "How many have this circumstance?" That’s what I was thinking, "I have a legacy, my father died early, I need to continue this. This is important stuff." But he was totally the opposite. Obviously I’m not listening to him... I mean, he meant well. I might have gone a different course if I’d taken his class, because he wouldn’t have let me to fall into my comfortable space.

HM: At that time, in the early '80s New York City, graffiti was everywhere. Your father’s art and lettering style was embraced and appropriated by many of the early graffiti artists. Do you recall the first time you saw his art tagged on a train or building?

MB: Right. Well, it was after a day at Jack Potter’s class and probably being traumatized. I was schlepping my half-ass boring drawings (laughter) to the subway and going back to Brooklyn. I’m waiting at the West 23rd street station, went down there, I remember it like it was yesterday, and sittin’ there minding my own business and then a non-stop N train comes by me... and I saw a whole car of Dead Bone Mountain. It had Punkerpans, it had Cheech Wizard, it had Lizards, it had Bodē Broads, all on the train and the person’s name. It went by me and it was a eureka moment. But I didn’t... I thought it was one insane person, "It’s gotta be that some crazy person is out there in the yards spray painting my father’s stuff for no apparent reason." I think I mentioned it to my wife and then I put it behind me because I just figured it was a fluke and I’d never see it again. And I didn’t see it again, until I moved back to San Francisco a year later.

I noticed that above The Stud, which was a famous gay bar in San Francisco, was a PW-17 from "Zooks," which just a few years earlier I was coloring for Heavy Metal. And it was never in color before, right? So, you know it was from Heavy Metal. Then I thought, "Well then, it’s more than one person then. And after that I started, little by little, meeting new graffiti people in the Bay area. And they said, “Oh yeah, your Dad’s huge. Check this out, check that out.” And people down on the train tracks in Berkeley were doing an "Erotic” page or a panel. The woman in a meditative pose with her head exploding, that was huge, like ten-feet, fifteen-feet tall on the tracks. So, I started hanging out with various graffiti artists in the Bay area.

Then I met Dondi when I was visiting in Brooklyn. Dondi knew that my mother in-law had a bodega. She was the only woman at the time that was running her own bodega. And she’d hire goons to watch over the store, so she didn’t have to deal with getting mugged and stuff. She’d give them free beer and they would hangout and watch over Elsa. Dondi knew this, so he would frequent the bodega and say, “When’s Mark coming? When’s Mark coming again?” “Oh, he’s coming soon,” and then one day I show up and he was there. He showed me his books but he didn't tell me about spray painting or going to the yards, he never talked about any of it. He wanted to know, “What was Vaughn like? What did he eat? How did he work?” He was a mega fan, and he was drawing these graffiti pieces that were beyond me. I was strictly a comic artist at that point.

HM: When did you pick up your first can of spray paint?

MB: It never crossed my mind when I was at School of Visual Arts. I just wasn’t thinking about it, I was just so wrapped up in trying to continue my father’s work. So, when I went back and I started hanging out with these graffiti artists that were doing my father’s characters, I realized this is what’s up. And so they gave me cans - but I sucked! It was like working with a club. It’s like, “Here’s a pencil... now here’s a club, try to draw with that.” And so I would try to do what they were doing, but I just swept it under the rug as a failure on my part. But the annoyance of people getting so good at it kept me trying. (laughter) "You’re so good at drawing Cheech Wizard, I gotta be able to do that!" How did they control that?

It was because Krylon and Rust-Oleum was all you had back then, it was scraps, you know? And the pressure of the cans was just immense. I didn’t know any tricks, and my friends... I don’t think those people were helping me, they didn’t want me to be too good (chuckle), “Let him struggle.” So, the can control was just out of my hands, I just couldn’t... until this one day, I actually tried to do it in public.

And that was done in Oakland, at the Piano Warehouse, 8th and Pine. My friend, Steve Heck, who was one of the original guys from the “Burning Man” days when it first started, he used to build bars out of grand pianos out in the desert and torch it. He said, “Hey, you know these graffiti guys, huh? Invite them over to paint, they can paint inside of the warehouse.” So I did and I was super green, but I had some good teachers there that kinda helped me – I couldn’t even sign my name right. I didn’t have the chops, but that first piece that I did ended up in Spraycan Art and Jim Prigoff suggested that I take a picture in front of it. I didn’t realize the importance of it, I just thought it was this guy who wanted something for his portfolio.

HM: That must have launched a whole new career for you?

MB: It did. I still sucked for a long time. But I got good at it. Especially once low-pressure cans came in along with multiple caps. Then I picked it up again and it was like painting with an airbrush. I was so happy, and I started excelling in it fairly quickly.

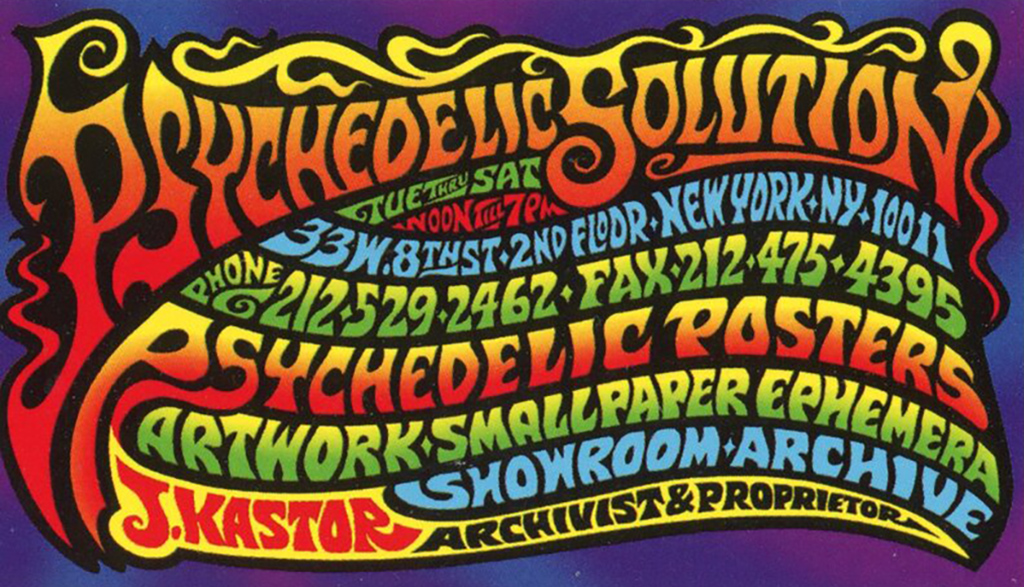

HM: I remember walking on 8th street in the Greenwich Village and seeing your name in a gallery space along with your dad’s. It was The Psychedelic Solution Gallery, which was focused primarily on psychedelic art and 1960s concert posters. How did that come about?

MB: Jacaebor Kastor was the first gallery owner to do comic book show of the art in NYC. No one was doing what he was in the 80s and 90s. He did the first Zap Show featuring Crumb, Spain, Griffin, Shelton, Williams and S Clay Wilson. He also did HR Geiger’s first show in NYC in that little gallery. People would line up around the block to get a peak of what was going down there. As they did for our show in 1993, I think every graff head and underground comic person in the know was there that night. So, cool you were there too, Dave!

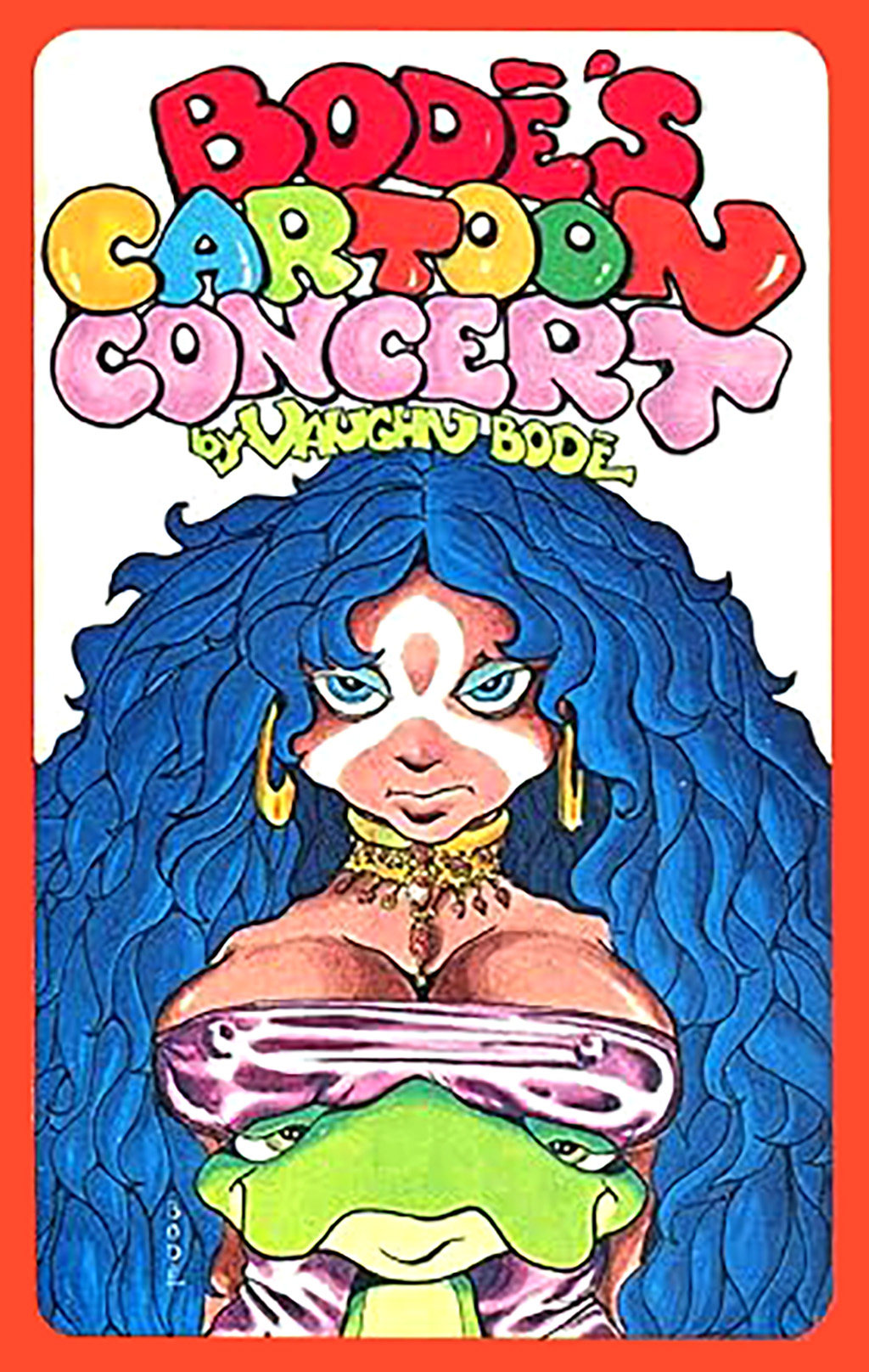

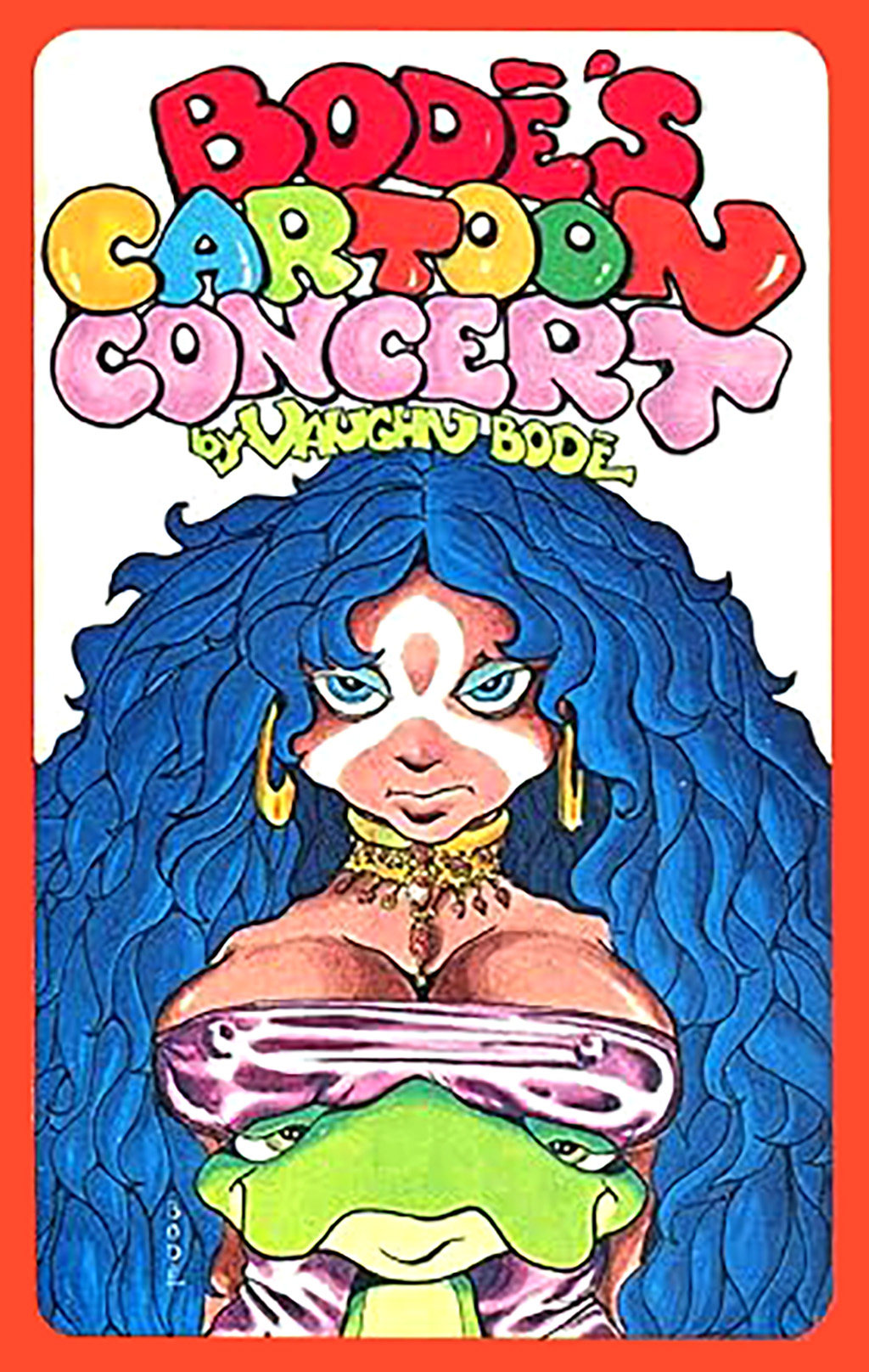

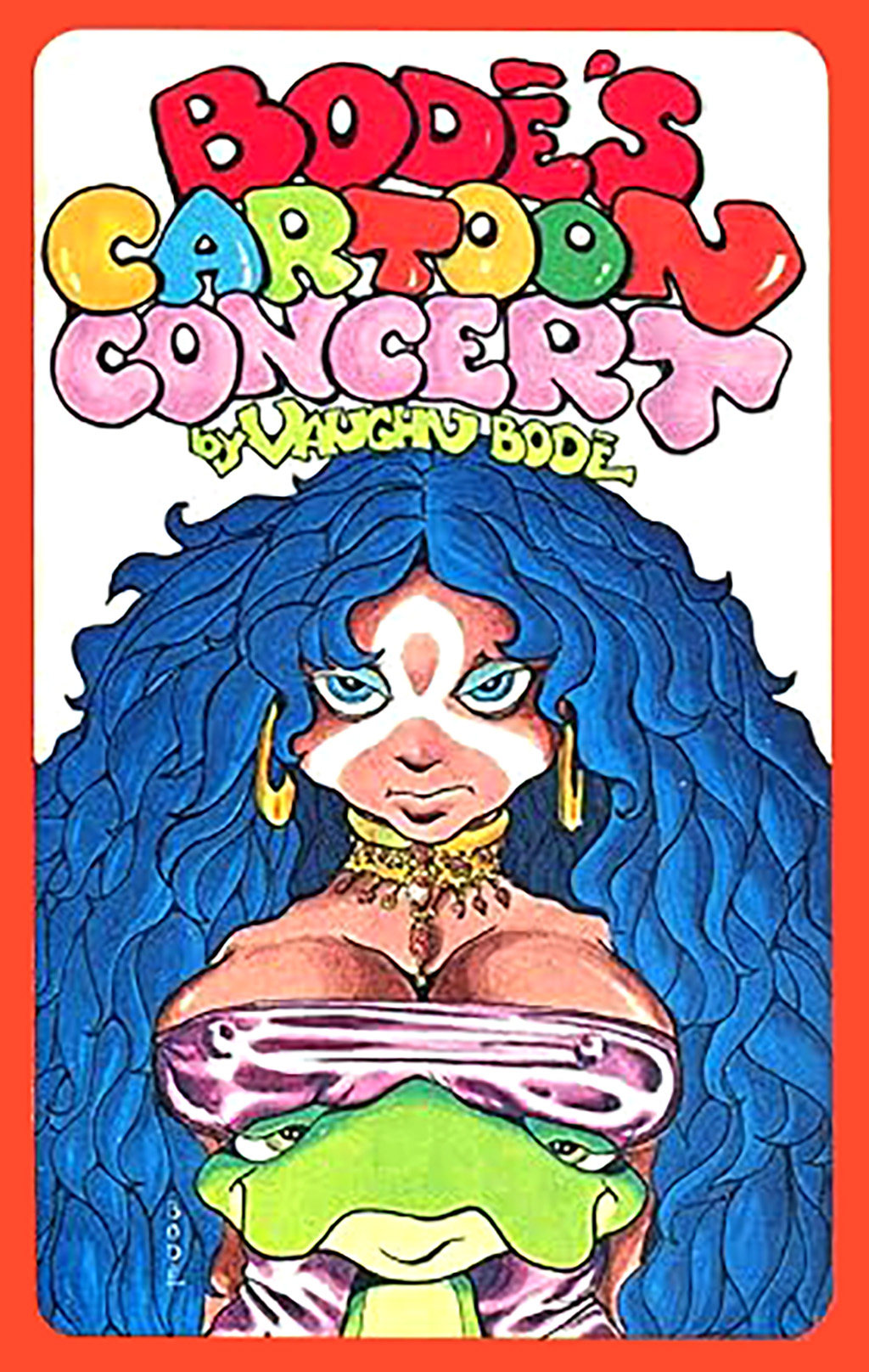

HM: Unfortunately, I wasn’t there for the opening night. I didn’t know the about the show until a few days after it’d opened. But I understand you performed the "Cartoon Concert" that night?

MB: I did my "Cartoon Concert," which was a combo of my father’s version, and my X-rated material, which I read aloud to slides of our works with sound effects and voices. It’s quite funny. It was difficult because it was a small place, but I think there were hundreds of people in there. And they all sat down. Because it was a small place I thought I wouldn’t need a microphone and I’d have this screen setup and the projector and everything... but I was wrong because the place was so packed, that your voice comes out and it drops.

HM: How did your father come up with the idea of performing his cartoons?

MB: My father had this desire to be acknowledged to get immediate response to his work. Most cartoonist, all cartoonist I’d say, don’t get that unless they’re drawing in public, at a convention or something. My father figured a way to perform his comic strips in front of a crowd. So, he came up with the Bodē pictography format, which was the panel separate from the word balloons. And so he photographed the panel with no balloon, and would read the comics (in the voice of a Bodē lizard) ”Ah gee Cheech, do a trick,” and Cheech would say (in the voice of Cheech), “Go jerkoff to the Bible, Fuzzballz.” He’d do all kinds of sound effects and everything – it was a live performance. There was nothing like since, maybe Windsor McCay.

HM: Right, one the first animators.

MB: We go all the way back to Windsor McCay where he stood behind the screen and he would do the voices for Gertie the Dinosaur. And that was the same concept that we did in the '70s with my Dad... it was really, really cool. He did it at colleges all over the United States and then he did it at a ballroom adjacent to the Louvre, in Paris, in ’74. And every cartoonist, everybody who was anybody in the comic book business in Paris, was there! I mean, Moebius was there! It changed his life.

HM: He was an amazing innovator to the medium and incredibly creative in such a short time.

MB: Ten years. He only worked professionally from 1965 to ’75... then he was gone. It’s amazing... like a comet coming in through the atmosphere and leaving just as quick. It’s phenomenal.

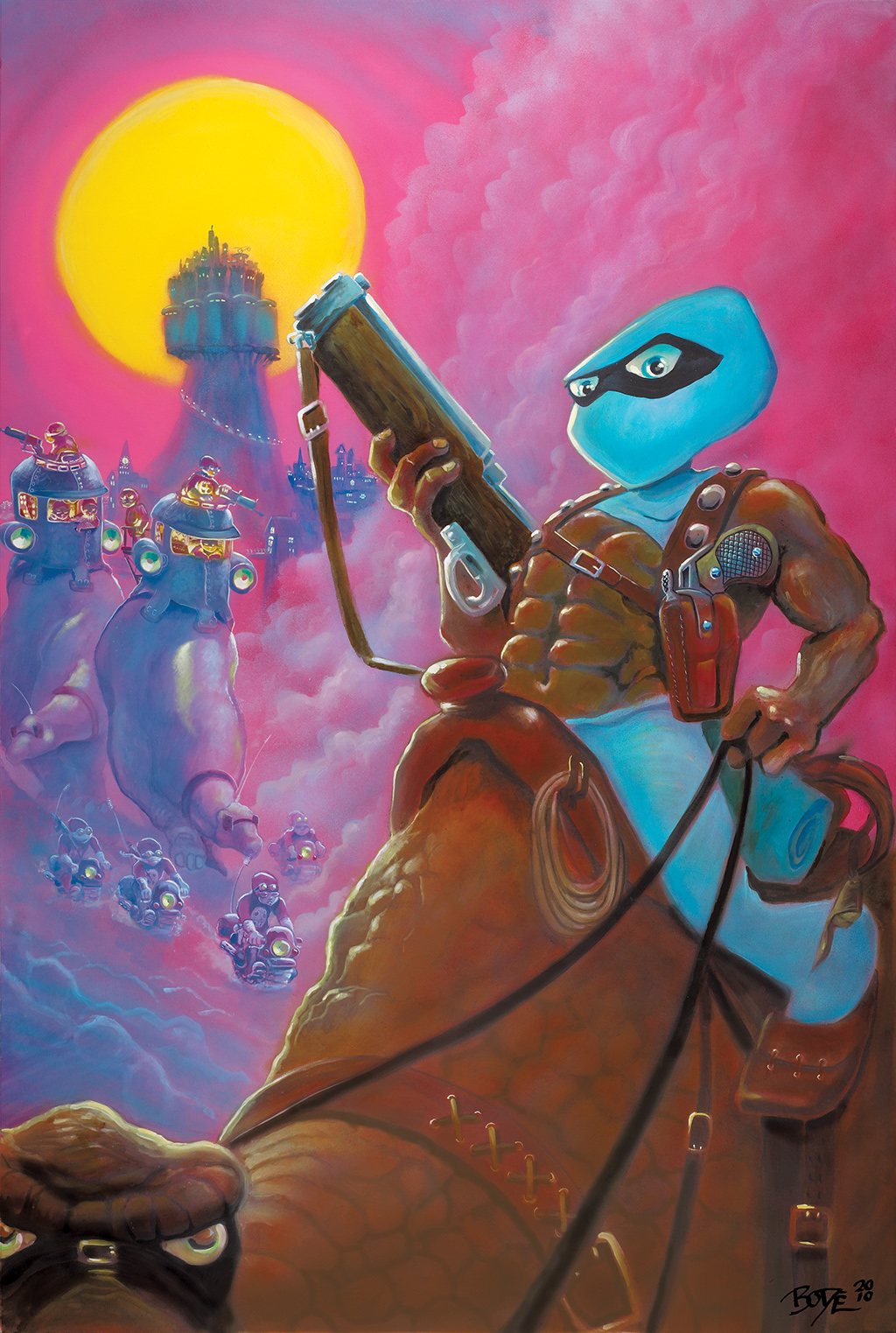

HM: The last time we’d met was in my office at DC Comics where I was the Executive Creative Director. You’d given me an autograph poster of Cobalt 60, which I still have, and you’d told me that it had been optioned by a movie studio, are there any updates to its status?

MB: Well, this has been going on for decades. It’s a dance, because all of the people like the talent scouts, animators, everyone gloms onto it, everyone is excited all the way up the pole. Then it gets to the money guy, “It’s just some obscure cartoonist from the '70s. Who wants to see that?!” (Laughter) And that’s what happens to it over and over again. It’s very frustrating. I feel it’s only a matter of time before it happens.

Zack Snyder, a big fan of Cobalt 60, and vowed in film school in New York that if he ever became a big director he would do Cobalt 60 as a movie. And he told me this himself, and even got the option with Universal. Later he got onto Watchmen and I got a tour of the Watchmen set and Zack actually said, “Get the chairs for Mark and Molly please.” And all these guys are like, “Huh?” (Laughter) "Who’s this guy?" I’m like, "I got my own director chair!" And a view right behind Zack. It was amazing and I thought, "This is it. Right after Watchmen, he’s gonna jump on Cobalt," but it kept getting bigger and bigger for him. I think Sucker Punch should have been Cobalt. Then he did Man of Steel, I mean, how do you compete against that? You know it, you’re from DC.

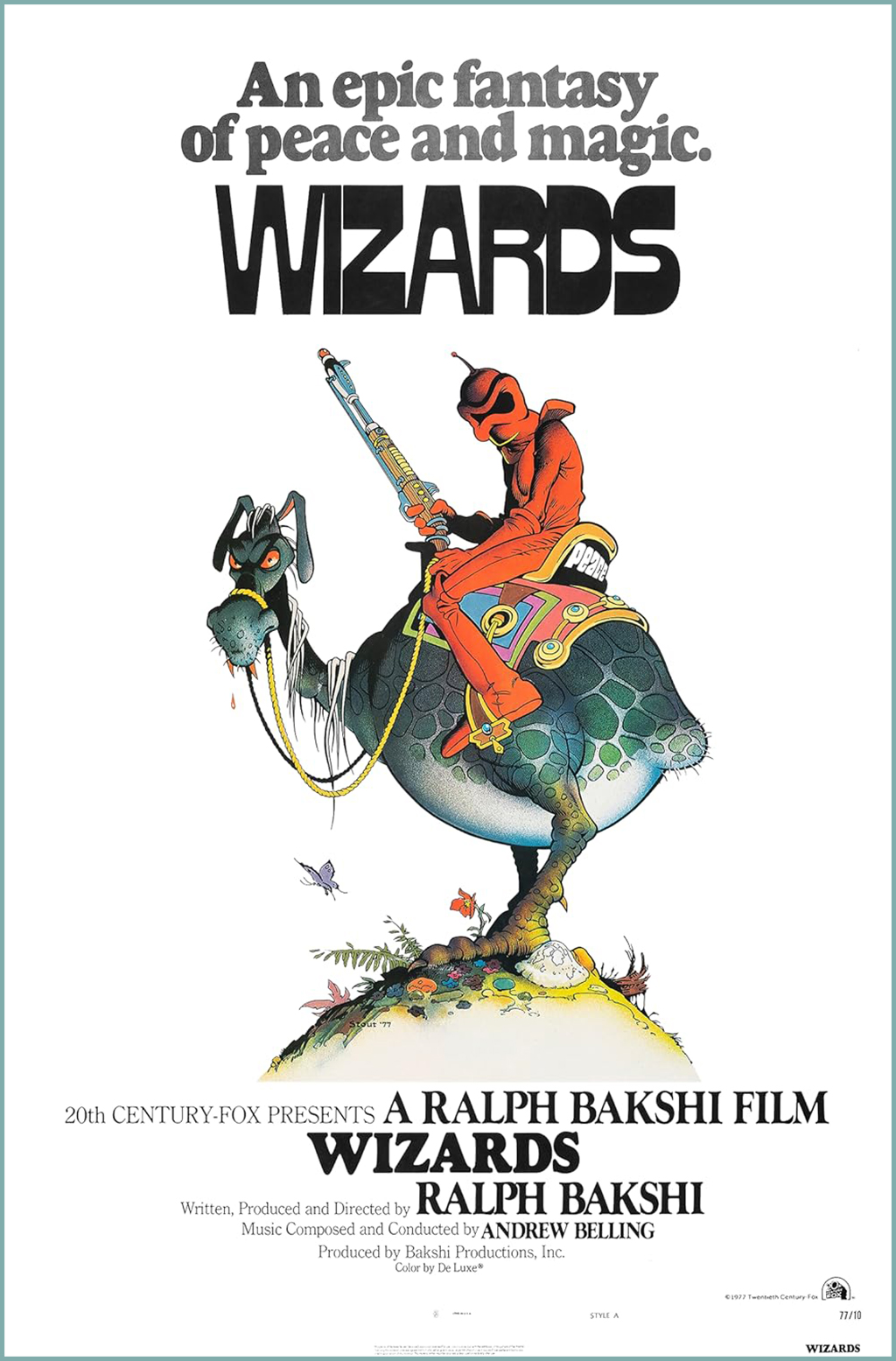

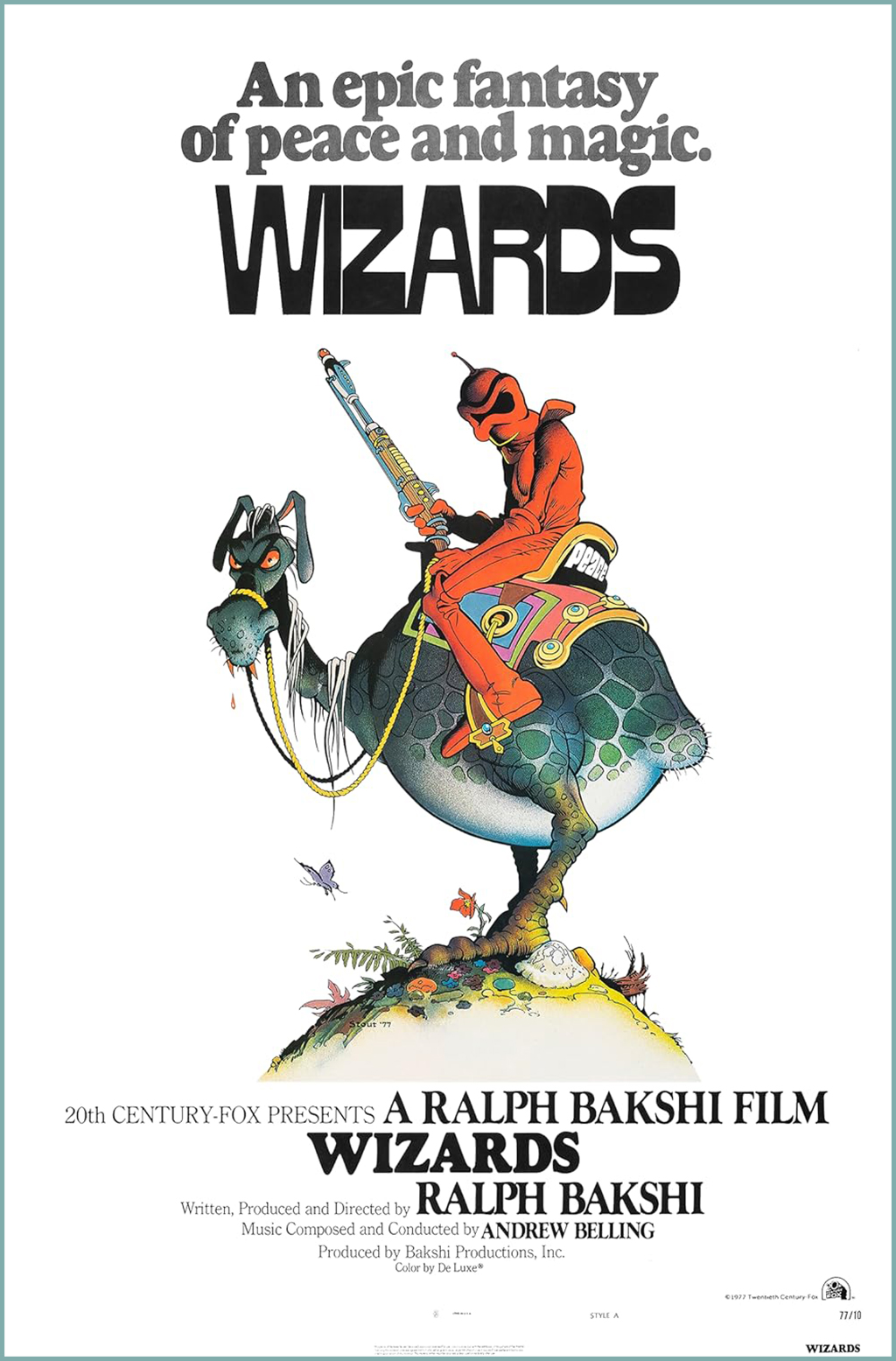

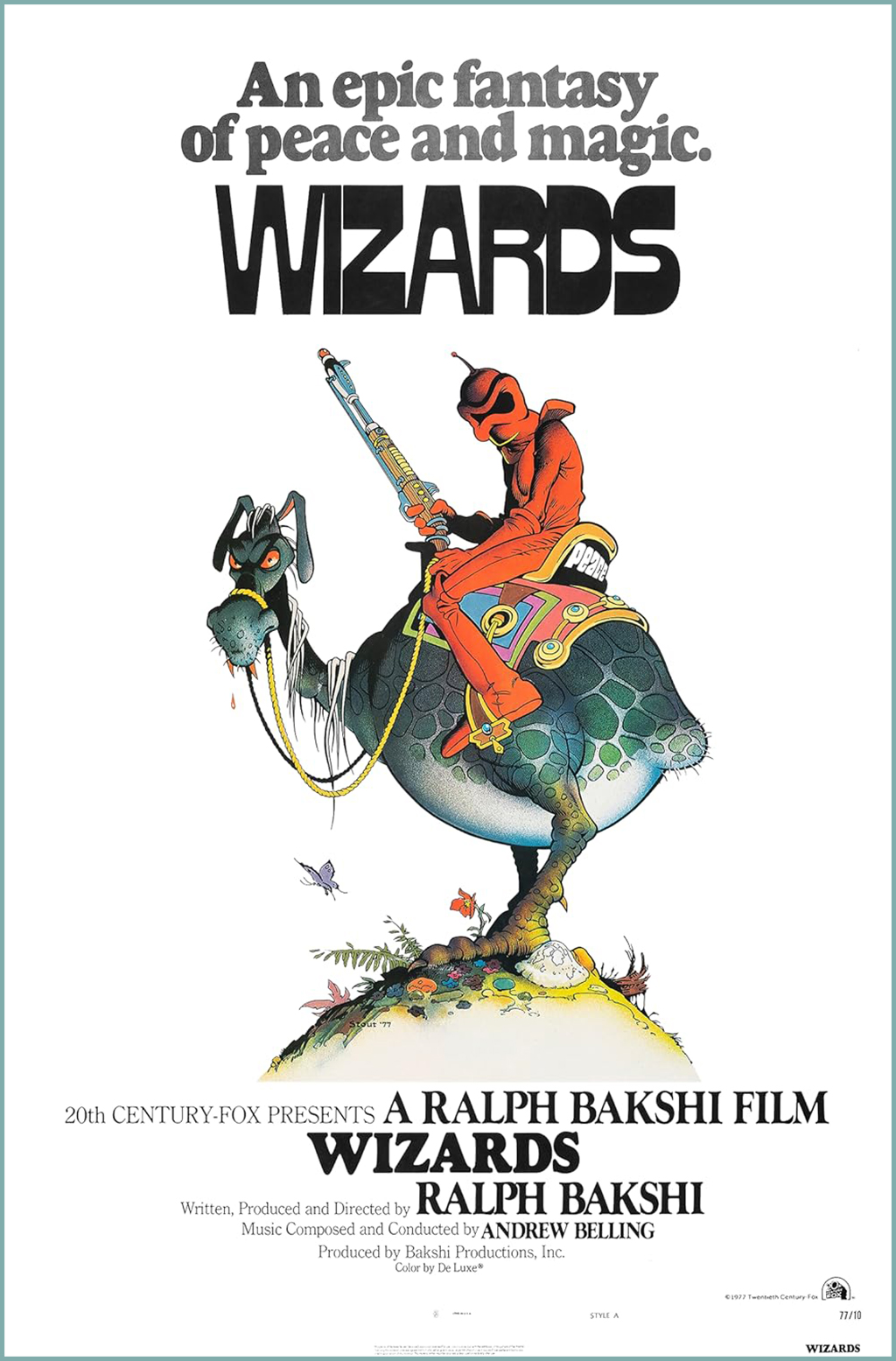

HM: We can’t talk about Cobalt 60 without talking about Wizards, the Ralph Bakshi animated feature film. The movie poster is a Cobalt 60 clone.

MB: It is. It’s been... yeah... let me take you back to my father’s relationship with Ralph. In 1968, Bakshi hadn’t quite had his first break yet, he wasn’t doing movies yet. He felt he wanted to be an agent to get all of these talented underground artists into animation movies. So, my father gave him stacks of work, including Cobalt 60. Bakshi would take them to animation studios and would get rejected, and this went on for a few years. Then things didn’t become so good.

Crumb, to this day, wants nothing to do with animation. Nothing! Ptui! And Ralph wanted to do nothing more than Fritz the Cat. He thought that was the golden goose that could change everything and make adult animation big. But Crumb wanted nothing to do with it and wouldn’t let him. So, the story goes that Crumb was over in Europe somewhere, and his wife and newly born child were here in San Francisco. Bakshi went to their house and laid a hundred-thousand dollar check on the table and said, sign here and this check is yours – and she’d never seen money like that in her life. They were selling Zap comics out of a stroller down in the Haight Street in San Francisco. And she signed it, she had the power of attorney, she didn’t read or change the contract. And it said in there that the property of Fritz the Cat is the property of Ralph Bakshi. So, when Crumb came back, he took him to court and lost.

My father said to Bakshi, “After what you did to Bob, we will work together over my dead body.” Bakshi kept calling to offer my Dad more and more money to do a Dead Bone movie or a Cheech Wizard movie, or whatever - he wanted to do a movie with Vaughn next. My father kept refusing. On the day Dad died, I answered the phone and it was Bakski, “Hi, is Vaughn there?” I answered, “No, he died today.” And he goes, “Oh... my condolences to the family,” and that was it, “click!”. And then he went to production on Wizards.

You know, my Mom and I were so broke at the time I think... sorry to spend so much time on such a horrible tale, but this is the truth of what happens in Hollywood.

My Mom and I were so broke, he could have thrown five-thousand, or ten-thousand dollars and my Mom would’ve signed... that’s how easy it could have been for him. I might not have owned Cobalt 60, which in the long run I’m glad she didn’t take an offer. It could have been easy for him, but he chose to keep Vaughn’s credit off and he never knew that Vaughn’s son would come along and revive Cobalt 60.

He must get it to this day, “Oh, you got a lot shit from Vaughn Bodē didn’t ya!” I’m sure he gets it all the time, because he called me to apologize eight years ago. There was a new Blu-Ray version of Wizards coming out at the time, “Mark, this is Ralph Bakshi (imitating him),” and I’m, “Okay, yeah? And?” “Well, your dad and I loved each other, and we need to move forward on the Wizards thing. I was very influenced and I just want to apologize for the influence there, 'cause we’re not going to live forever you know, and I wanna tell ya and I wanna come straight, and...” I think he was looking for me to give him my blessing, but I didn’t. I didn’t want to be that guy, and I couldn’t.

I think he had a lot of guilt.

There’s a new version of Wizards coming out on Blu-Ray... and I get this every time I go to a convention, “So, you did Wizards, huh?” or “You get all your stuff from Wizards or Bakshi, huh?” We get it all the time, it’s a curse. That’s why I have no qualms bullshittin’ about it.

HM: Well, enough about him, let’s get back to you. Can you tell us what are your future plans? Do you have any plans for any art shows or mural commissions?

MB: Ah gosh, I had all these plans. Every year around November, I make my plans for the next year. And this year just went to complete utter shit (laughter). I just couldn’t get anything done. But yeah, as far as murals go... it was pretty much art shows. What I do is, I’ll do an art show and then I’ll do a mural to promote the art show, get on the internet and get everyone excited, or do an event after the opening where everyone can paint homages to Vaughn Bodē. There’s no other artist that gets so many homages, all of these tributes all over the world. I get to see for my father, like a dead man able to see the future, I can see it for him and be moved by it. There have been hundreds - perhaps thousands, if you consider efforts from individual artists. He’s the only one where everyone gets together and says, “Let’s get together to do a Bodē event” and everybody paints their version of their favorite characters, there’s nobody like it, there’s nobody that shakes a stick at that.

HM: Yes, your dad has left an indelible gift to the world and continues to do so with your help. Can you share with us a memory of you and him?

MB: Being with him was a constant adventure. For instance, we were out in the woods by the house that Jeffery (Jones) and my dad were sharing together, and it was winter time, we come across a little bridge and a frozen creek. There was a frog frozen in the ice. And my father says, “Look, look Mark! It’s a frog and he’s just sleeping. He’s going to wake up in the spring, and he’s going to be a happy frog again!” And Jeff was like, “No, Vaughn. He’s dead! He needs to bury himself in mud to survive. His little body is crisp! It’s like an ice-cube.” And my dad’s like, “Don’t listen to your uncle Jeff, Mark. He’s coming back to be a happy little frog again.“

HM: Lastly, what’s in the horizon for Mark Bode?

MB: I have an 80-page Cobalt 60 story, ”The Death of Cobalt 60.” I have finished writing and penciling it. I am looking to finish it but I don’t have a publisher slated as of yet. Also, at the moment I have several fine art canvas prints in production from some of the work I did in issue 300 of HM by CYMK Gallery in Chicago.

Also, I see my father as a Tolkien or a Baum-type creator. Neither of those authors got to see their works on the big screen. I am hoping to beat the odds and see Dad's creations reach their full potential someday soon. A documentary on my father is being produced called THE BOOK OF VAUGHN by director Nick Francis. It’s been in the works for three years now. Nick has interviewed many artists and friends of Vaughn’s.

Mark's Web Site

MARK BODĒ Interview

An Interview with Mark Bodē by David Erwin

As a young boy, Mark grew up surrounded by a world of imaginary characters and places created and told to him by his father, Vaughn Bodē. As the son of a legendary artist whose influence has touched everything from cartoons to graffiti, Mark shares his memories in finding is own path, while carrying the responsibility of his father’s creations and art over the decades after his untimely death.

HEAVY METAL: You’ve been drawing since you were 3-years-old and published in Heavy Metal by the time you reached 15. Recently, you returned to Heavy Metal with new works. How do you feel about your return in Heavy Metal’s milestone issue #300?

MARK BODĒ: Dave, it’s an honor, it really is. So much has gone on and I’ve gone all over the world with our characters, comic cons, and art shows, mural events, movie premieres and during it all Heavy Metal was there and it’s amazing to be back in the saddle spinning some new stories for new followers in issue 300. It is the greatest American Science Fiction Fantasy Magazine of all time and I’m damn proud to be in it once again.

HM: Your first project for Heavy Metal was coloring your father, Vaughn’s, unfinished work "Zooks, the First Lizard in Orbit" – you were 15 years old at the time. How did this come about?

MB: Well, in 1978 I was attending The Art School in Oakland California. I was in 10th grade and wasn’t the best student to my teachers. I grew up around the best illustrators and painters in comics and pop culture. I must admit, I knew it and acted pretty cocky, as teens tend to do. People like Jeffery Catherine Jones, Bernie Wrightson, and Larry Todd - to name a few - were my uncles. There seemed nothing these art teachers could teach me that I did not know already. When at the time, Editor-in-Chief of Heavy Metal, Matty Simmons, asked if we had more Vaughn Bodē art for the magazine. My mother, Barbara, answered, "Yes, we have some black-and-white strips." Matty wanted colored art. It was then that Larry Todd, who had taken over mentoring my apprenticeship in art, suggested, "You color it, Mark." I was sure the project would get turned down if we pitched the idea. Vaughn’s 15-year-old son was to finish his father's work? So, it was decided I would ghost the project with Larry teaching me some tricks as I go. It worked and was printed a few months later. When I look now on those pages, they hold up very well. I can say, "Good job, kiddo" to my much younger self. That job and getting paid for it really gave me the confidence to follow in my fathers’ footsteps and to go pro and not look back. I must be still the youngest to work for HM. If there is another let me know.

HM: For #300 you’ve completed and added additional pages to his unfinished "SUNPOT, Dr. Electric Meets Da’ Repro Man" story. How did you come to choose Sunpot over other properties?

MB: Well, now that it's hundreds of issues later and I'm in my 50s, I can still find excitement to work and spin some new stories. When I was a teen, there were three properties that Larry Todd said I should expand on. The first being Cobalt 60. Larry suggested this first because Science Fiction is the wave of the future and Vaughn did not expand enough on that world, which is our radioactive future on Earth. Vaughn only did 20 pages of story and art for this property and suggested a cast of unused characters for a longer story that never panned out, 'til Larry and I turned it into a 500+ page epic. Second was Sunpot. Sunpot was an erotic sarcastic take on life in a chaotic and insane organic spaceship. Vaughn did a 30-page story broken up into chapters that ran in the pulp Sci Fi magazine Galaxy in the early '70s. My father wanted a better page rate from the editors and was turned down, even after the strip had increased the magazine's print run. So, Vaughn turned in his final installment, "SUNPOT is DEAD," where the entire crew hits a toxic gas cloud and dies. The magazine editors were speechless and the magazine tanked a few issues after Vaughn terminated working for them. The third property is Cheech Wizard, but I agreed with Larry that Cheech was too personal to Vaughn. I mean, Vaughn is Cheech Wizard, he is who is under the hat. So we should not continue that property... at least not for now.

HM: What was that like for you to revisit your father's characters after all these years?

MB: So, for 40 years I have been secretly yearning to expand on Sunpot. It has always been on a backburner wanting to come forth. When you and the staff approached me about some unpublished Vaughn work that could grace issue 300, I had a hard time finding stuff that was finished because Vaughn was always about getting in print. I was pawing through old college material of my Dad’s that was cool, but didn’t have the HM edge. I had a eureka moment, like Dad tapped me on the shoulder and whispered, "SUNPOT!!!" So, I dove into drawing up a short story and doing some pencils and here we are! Like old friends come back from the dead to get into trouble again. These characters are under my skin and all I gotta do is give them energy and they kind of start talking and threading their own stories. It has been pure joy and a way to spread the world of Bodē to a new group of readers.

HM: Your father left behind a huge universe of characters and worlds, just how big is that universe?

MB: Oh, unbelievably deep. I keep trying to organize it, I keep trying to delve into it every decade or so. A lot of it were drawn on whatever was around the house, garbage bags, laundry bags. Whatever he had, he would draw on. I would say thousands and thousands of characters are sitting there and could be added to or updated. His most prolific time, I would say was between 1958 and 1962, where he created thousands of worlds and characters, almost on a daily basis. He wouldn’t just doodle some character, he would create moons and planets and name them all. Then go into the planet and populate it with cities, towns, rivers, streams and name them. Then populate them with characters and let their stories unfold from there.

I don’t know how he did it. I know he ate a lot of Hostess Snowballs and Twinkies and coffee... a lot of coffee. And zoom around all our heads as if we were sitting still back in the caveman days. I mean, he was zooming and stay up for two days at a time just on the junk food and coffee.

HM: Did your father tell you stories with his characters?

MB: My childhood was filled with stories. I know at times Dad was testing new ideas on me at bedtime. The bear went over the mountain not to see what he could see, but to visit his pal Cheech. I looked forward to those stories. They had a basic structure that always went off in a bizarre and fantastical way by the time, "Good night, Mark" and the kiss on the head came. Every night my head was full.

HM: On the subject of revisiting your father’s characters, you’ve also written and illustrated a new short story based on Cobolt-60 that will be featured in Heavy Metal #302. What inspiration for this?

MB: Well, that was a bit of a departure from Cobalt’s normal world. As I was taught, "Don’t draw what you have to draw, always draw what you want to draw." I stared at the empty page and wanted to draw a zero-gravity sex scene with a Barbarella flair. "How’s that work?" I thought, "Hmmm, maybe I should get out some of my fears of this Covid anxiety my wife and family are experiencing." A dark, Covid-19-inspired short story unfolded. It’s a bit of a bummer, but hey, I had fun drawing it. Mission accomplished! (laughs)

HM: The first time I’d met you, I was a student at New York’s School of Visual Arts. You were signing your original comic book Miami Mice at a small, eclectic, hole-in-the-wall shop in Soho. Obviously, it’s a take on the television show Miami Vice, but can you tell us what compelled you to enter into the Indy comic book market?

MB: Sohozat! What a great store that was in the village I believe? I remember meeting you there for sure, I was glad somebody showed up! Thanks, Dave! (laughter)

Well, I also meet Henry Chalfant for the first time there, too, and Mare139... him and his brother, Kel, did massive top to bottom cars with Bodē characters in the early '80s into the '90s. Miami Mice was my first full-on comic book, outside of my father's worlds. It was a design I saw on carnival prizes and t-shirts. The Ninja Turtles had just begun selling out comics and hadn’t made it on TV yet. A black-and-white funny animal boom seemed to be taking hold of the comics scene. My wife, Molly, suggested that it would make a great comic book. I did some sketches of what I’d do with the parody and pitched the idea to Fred Todd of Rip Off Press, they did the Freak Brothers underground comic with Gilbert Shelton. They printed it on a whim and in one year’s time we sold 150,000 comics. Here it was my very first solo venture, I thought I had the golden touch. I ended the Mice in issue #4 with a TMNT and Cerebus crossover and went to another more interesting project... that did under a 2000 print run. Live and learn.

I ended up joining Kevin Eastman’s team of artists and we went onto have the time of our lives being on that wave. Yes, comics were very, very, good to me. The Internet changed all that, but damn... it was a hell of a ride!

HM: Would you go back to Miami Mice?

MB: (Laughter) It was bad! I was, "This is so not me." The over-the-top violence, the guns, and then in my studio, I had a mouse problem and mice were running over my feet while drawing it. I started taking my BB-gun and hiding under my drawing table waiting from them to come out of the walls... (laughter) I was, "It’s time to stop, Mark!"

HM: This is a side note, I recall when you were signing, your beautiful wife accompanied you or maybe she was still your girlfriend at the time, looking very much like a Bodē Broad. Has that ever crossed you mind? Tell me a little about Molly.

MB: Yes absolutely. When we met, she was a professional belly dancer. When I saw her dance at the Haight Street Fair in the late '70s, I said, "I must make her mine!" Love, infatuation, lust, the whole deal. I studied Arabic and Moroccan music to accompany her performances for many, many years, mostly on the west coast. She is my muse, my own personal Bodē Broad and I do not need to use models when I draw women... her looks, her hips, her prowess, is engrained into my DNA forever!

Molly also joined the Mirage Studios/Ninja Turtles team as an art-licensing assistant. She has been a huge help when anyone wants to license my images.

HM: I’d recently learned that you were also a student at SVA a few years before me, studying Fine Arts, also the same as me. What was your experience like attending there?

MB: I loved it. I was so honored to be accepted in there. I didn’t... I don’t think I got any scholarship or anything, but I was so excited. And I couldn’t believe Molly, my girlfriend at the time (who is now my wife), she lived in Brooklyn and we lived in San Francisco where we met. And she, out of love, moved back to Brooklyn even though she didn’t want to.

HM: I’m surprised you majored in Fine Arts when SVA has one of the best comic book departments.

MB: Well, I didn’t have a choice being a freshman. You had to take all the basics. And, I really wanted to be in Art Spiegelman’s class. There were certain people I was really looking forward to the next year. But we ended up moving back to San Francisco after two semesters, so I was just there for my basics. And I had Jack Potter. Does that ring a bell?

HM: No, I don’t know him.

MB: Well, he was a Yul-Brynner-type looking guy, and acted more arrogant than Yul Brynner. He would teach life drawing, “Five-minute pose, five-minute pose...” and you’re trying to keep up with his assignments. He’s like, “Change the pose, change the pose!” Then he’d walk around to see what everybody was doing... and he’d stop behind me, and a feeling of doom would happen – it wasn’t a good stop. I’d drawn a Bodē Broad of the woman sitting in the middle of the room. He was, “WHAT IS THAT?! Bubbly, cloudy drawing!” And I’m like, “It’s a Bodē Broad.” He ripped my drawing off the drawing board and tore it up! “DRAW AGAIN! USE YOUR EYES!” and I was, "Oh my God, I’m not going to survive this."

Another time, I was thinking about dropping my name just so I’d do better in the class. But at one point, he said, “One thing I despise are SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF ARTISTS! They’ve got this FIXATED WAY OF DRAWING AND THINKING! I’M GOING TO BREAK THEM DOWN!” Aaaah! I was so traumatized I didn’t say a damn thing after that. But he changed the way I think. He said, “Half of you will go onto BORING CAREERS! Look at me!” And then right outside there was a thunderstorm, “BA-LOOSH!” with lightning, and then he goes, “SEE!” (laughter)

But Spiegelman... I was actually working on "Yellow Hat." I was working for Archie Goodwin, and all my all my classmates were jealous because I was working for a major magazine, which wasn’t surprising because of who my Dad was... I didn’t give myself credit. I showed "Yellow Hat" to Spiegelman because I wanted to take his class and thought he would be like, “Yeah! Following your father, cool, go Mark,” but he didn’t say that, he said, “You got your father down, move on to your own stuff.” Huh? "How many have this circumstance?" That’s what I was thinking, "I have a legacy, my father died early, I need to continue this. This is important stuff." But he was totally the opposite. Obviously I’m not listening to him... I mean, he meant well. I might have gone a different course if I’d taken his class, because he wouldn’t have let me to fall into my comfortable space.

HM: At that time, in the early '80s New York City, graffiti was everywhere. Your father’s art and lettering style was embraced and appropriated by many of the early graffiti artists. Do you recall the first time you saw his art tagged on a train or building?

MB: Right. Well, it was after a day at Jack Potter’s class and probably being traumatized. I was schlepping my half-ass boring drawings (laughter) to the subway and going back to Brooklyn. I’m waiting at the West 23rd street station, went down there, I remember it like it was yesterday, and sittin’ there minding my own business and then a non-stop N train comes by me... and I saw a whole car of Dead Bone Mountain. It had Punkerpans, it had Cheech Wizard, it had Lizards, it had Bodē Broads, all on the train and the person’s name. It went by me and it was a eureka moment. But I didn’t... I thought it was one insane person, "It’s gotta be that some crazy person is out there in the yards spray painting my father’s stuff for no apparent reason." I think I mentioned it to my wife and then I put it behind me because I just figured it was a fluke and I’d never see it again. And I didn’t see it again, until I moved back to San Francisco a year later.

I noticed that above The Stud, which was a famous gay bar in San Francisco, was a PW-17 from "Zooks," which just a few years earlier I was coloring for Heavy Metal. And it was never in color before, right? So, you know it was from Heavy Metal. Then I thought, "Well then, it’s more than one person then. And after that I started, little by little, meeting new graffiti people in the Bay area. And they said, “Oh yeah, your Dad’s huge. Check this out, check that out.” And people down on the train tracks in Berkeley were doing an "Erotic” page or a panel. The woman in a meditative pose with her head exploding, that was huge, like ten-feet, fifteen-feet tall on the tracks. So, I started hanging out with various graffiti artists in the Bay area.

Then I met Dondi when I was visiting in Brooklyn. Dondi knew that my mother in-law had a bodega. She was the only woman at the time that was running her own bodega. And she’d hire goons to watch over the store, so she didn’t have to deal with getting mugged and stuff. She’d give them free beer and they would hangout and watch over Elsa. Dondi knew this, so he would frequent the bodega and say, “When’s Mark coming? When’s Mark coming again?” “Oh, he’s coming soon,” and then one day I show up and he was there. He showed me his books but he didn't tell me about spray painting or going to the yards, he never talked about any of it. He wanted to know, “What was Vaughn like? What did he eat? How did he work?” He was a mega fan, and he was drawing these graffiti pieces that were beyond me. I was strictly a comic artist at that point.

HM: When did you pick up your first can of spray paint?

MB: It never crossed my mind when I was at School of Visual Arts. I just wasn’t thinking about it, I was just so wrapped up in trying to continue my father’s work. So, when I went back and I started hanging out with these graffiti artists that were doing my father’s characters, I realized this is what’s up. And so they gave me cans - but I sucked! It was like working with a club. It’s like, “Here’s a pencil... now here’s a club, try to draw with that.” And so I would try to do what they were doing, but I just swept it under the rug as a failure on my part. But the annoyance of people getting so good at it kept me trying. (laughter) "You’re so good at drawing Cheech Wizard, I gotta be able to do that!" How did they control that?

It was because Krylon and Rust-Oleum was all you had back then, it was scraps, you know? And the pressure of the cans was just immense. I didn’t know any tricks, and my friends... I don’t think those people were helping me, they didn’t want me to be too good (chuckle), “Let him struggle.” So, the can control was just out of my hands, I just couldn’t... until this one day, I actually tried to do it in public.

And that was done in Oakland, at the Piano Warehouse, 8th and Pine. My friend, Steve Heck, who was one of the original guys from the “Burning Man” days when it first started, he used to build bars out of grand pianos out in the desert and torch it. He said, “Hey, you know these graffiti guys, huh? Invite them over to paint, they can paint inside of the warehouse.” So I did and I was super green, but I had some good teachers there that kinda helped me – I couldn’t even sign my name right. I didn’t have the chops, but that first piece that I did ended up in Spraycan Art and Jim Prigoff suggested that I take a picture in front of it. I didn’t realize the importance of it, I just thought it was this guy who wanted something for his portfolio.

HM: That must have launched a whole new career for you?

MB: It did. I still sucked for a long time. But I got good at it. Especially once low-pressure cans came in along with multiple caps. Then I picked it up again and it was like painting with an airbrush. I was so happy, and I started excelling in it fairly quickly.

HM: I remember walking on 8th street in the Greenwich Village and seeing your name in a gallery space along with your dad’s. It was The Psychedelic Solution Gallery, which was focused primarily on psychedelic art and 1960s concert posters. How did that come about?

MB: Jacaebor Kastor was the first gallery owner to do comic book show of the art in NYC. No one was doing what he was in the 80s and 90s. He did the first Zap Show featuring Crumb, Spain, Griffin, Shelton, Williams and S Clay Wilson. He also did HR Geiger’s first show in NYC in that little gallery. People would line up around the block to get a peak of what was going down there. As they did for our show in 1993, I think every graff head and underground comic person in the know was there that night. So, cool you were there too, Dave!

HM: Unfortunately, I wasn’t there for the opening night. I didn’t know the about the show until a few days after it’d opened. But I understand you performed the "Cartoon Concert" that night?

MB: I did my "Cartoon Concert," which was a combo of my father’s version, and my X-rated material, which I read aloud to slides of our works with sound effects and voices. It’s quite funny. It was difficult because it was a small place, but I think there were hundreds of people in there. And they all sat down. Because it was a small place I thought I wouldn’t need a microphone and I’d have this screen setup and the projector and everything... but I was wrong because the place was so packed, that your voice comes out and it drops.

HM: How did your father come up with the idea of performing his cartoons?

MB: My father had this desire to be acknowledged to get immediate response to his work. Most cartoonist, all cartoonist I’d say, don’t get that unless they’re drawing in public, at a convention or something. My father figured a way to perform his comic strips in front of a crowd. So, he came up with the Bodē pictography format, which was the panel separate from the word balloons. And so he photographed the panel with no balloon, and would read the comics (in the voice of a Bodē lizard) ”Ah gee Cheech, do a trick,” and Cheech would say (in the voice of Cheech), “Go jerkoff to the Bible, Fuzzballz.” He’d do all kinds of sound effects and everything – it was a live performance. There was nothing like since, maybe Windsor McCay.

HM: Right, one the first animators.

MB: We go all the way back to Windsor McCay where he stood behind the screen and he would do the voices for Gertie the Dinosaur. And that was the same concept that we did in the '70s with my Dad... it was really, really cool. He did it at colleges all over the United States and then he did it at a ballroom adjacent to the Louvre, in Paris, in ’74. And every cartoonist, everybody who was anybody in the comic book business in Paris, was there! I mean, Moebius was there! It changed his life.

HM: He was an amazing innovator to the medium and incredibly creative in such a short time.

MB: Ten years. He only worked professionally from 1965 to ’75... then he was gone. It’s amazing... like a comet coming in through the atmosphere and leaving just as quick. It’s phenomenal.

HM: The last time we’d met was in my office at DC Comics where I was the Executive Creative Director. You’d given me an autograph poster of Cobalt 60, which I still have, and you’d told me that it had been optioned by a movie studio, are there any updates to its status?

MB: Well, this has been going on for decades. It’s a dance, because all of the people like the talent scouts, animators, everyone gloms onto it, everyone is excited all the way up the pole. Then it gets to the money guy, “It’s just some obscure cartoonist from the '70s. Who wants to see that?!” (Laughter) And that’s what happens to it over and over again. It’s very frustrating. I feel it’s only a matter of time before it happens.

Zack Snyder, a big fan of Cobalt 60, and vowed in film school in New York that if he ever became a big director he would do Cobalt 60 as a movie. And he told me this himself, and even got the option with Universal. Later he got onto Watchmen and I got a tour of the Watchmen set and Zack actually said, “Get the chairs for Mark and Molly please.” And all these guys are like, “Huh?” (Laughter) "Who’s this guy?" I’m like, "I got my own director chair!" And a view right behind Zack. It was amazing and I thought, "This is it. Right after Watchmen, he’s gonna jump on Cobalt," but it kept getting bigger and bigger for him. I think Sucker Punch should have been Cobalt. Then he did Man of Steel, I mean, how do you compete against that? You know it, you’re from DC.

HM: We can’t talk about Cobalt 60 without talking about Wizards, the Ralph Bakshi animated feature film. The movie poster is a Cobalt 60 clone.

MB: It is. It’s been... yeah... let me take you back to my father’s relationship with Ralph. In 1968, Bakshi hadn’t quite had his first break yet, he wasn’t doing movies yet. He felt he wanted to be an agent to get all of these talented underground artists into animation movies. So, my father gave him stacks of work, including Cobalt 60. Bakshi would take them to animation studios and would get rejected, and this went on for a few years. Then things didn’t become so good.

Crumb, to this day, wants nothing to do with animation. Nothing! Ptui! And Ralph wanted to do nothing more than Fritz the Cat. He thought that was the golden goose that could change everything and make adult animation big. But Crumb wanted nothing to do with it and wouldn’t let him. So, the story goes that Crumb was over in Europe somewhere, and his wife and newly born child were here in San Francisco. Bakshi went to their house and laid a hundred-thousand dollar check on the table and said, sign here and this check is yours – and she’d never seen money like that in her life. They were selling Zap comics out of a stroller down in the Haight Street in San Francisco. And she signed it, she had the power of attorney, she didn’t read or change the contract. And it said in there that the property of Fritz the Cat is the property of Ralph Bakshi. So, when Crumb came back, he took him to court and lost.

My father said to Bakshi, “After what you did to Bob, we will work together over my dead body.” Bakshi kept calling to offer my Dad more and more money to do a Dead Bone movie or a Cheech Wizard movie, or whatever - he wanted to do a movie with Vaughn next. My father kept refusing. On the day Dad died, I answered the phone and it was Bakski, “Hi, is Vaughn there?” I answered, “No, he died today.” And he goes, “Oh... my condolences to the family,” and that was it, “click!”. And then he went to production on Wizards.

You know, my Mom and I were so broke at the time I think... sorry to spend so much time on such a horrible tale, but this is the truth of what happens in Hollywood.

My Mom and I were so broke, he could have thrown five-thousand, or ten-thousand dollars and my Mom would’ve signed... that’s how easy it could have been for him. I might not have owned Cobalt 60, which in the long run I’m glad she didn’t take an offer. It could have been easy for him, but he chose to keep Vaughn’s credit off and he never knew that Vaughn’s son would come along and revive Cobalt 60.

He must get it to this day, “Oh, you got a lot shit from Vaughn Bodē didn’t ya!” I’m sure he gets it all the time, because he called me to apologize eight years ago. There was a new Blu-Ray version of Wizards coming out at the time, “Mark, this is Ralph Bakshi (imitating him),” and I’m, “Okay, yeah? And?” “Well, your dad and I loved each other, and we need to move forward on the Wizards thing. I was very influenced and I just want to apologize for the influence there, 'cause we’re not going to live forever you know, and I wanna tell ya and I wanna come straight, and...” I think he was looking for me to give him my blessing, but I didn’t. I didn’t want to be that guy, and I couldn’t.

I think he had a lot of guilt.

There’s a new version of Wizards coming out on Blu-Ray... and I get this every time I go to a convention, “So, you did Wizards, huh?” or “You get all your stuff from Wizards or Bakshi, huh?” We get it all the time, it’s a curse. That’s why I have no qualms bullshittin’ about it.

HM: Well, enough about him, let’s get back to you. Can you tell us what are your future plans? Do you have any plans for any art shows or mural commissions?

MB: Ah gosh, I had all these plans. Every year around November, I make my plans for the next year. And this year just went to complete utter shit (laughter). I just couldn’t get anything done. But yeah, as far as murals go... it was pretty much art shows. What I do is, I’ll do an art show and then I’ll do a mural to promote the art show, get on the internet and get everyone excited, or do an event after the opening where everyone can paint homages to Vaughn Bodē. There’s no other artist that gets so many homages, all of these tributes all over the world. I get to see for my father, like a dead man able to see the future, I can see it for him and be moved by it. There have been hundreds - perhaps thousands, if you consider efforts from individual artists. He’s the only one where everyone gets together and says, “Let’s get together to do a Bodē event” and everybody paints their version of their favorite characters, there’s nobody like it, there’s nobody that shakes a stick at that.

HM: Yes, your dad has left an indelible gift to the world and continues to do so with your help. Can you share with us a memory of you and him?

MB: Being with him was a constant adventure. For instance, we were out in the woods by the house that Jeffery (Jones) and my dad were sharing together, and it was winter time, we come across a little bridge and a frozen creek. There was a frog frozen in the ice. And my father says, “Look, look Mark! It’s a frog and he’s just sleeping. He’s going to wake up in the spring, and he’s going to be a happy frog again!” And Jeff was like, “No, Vaughn. He’s dead! He needs to bury himself in mud to survive. His little body is crisp! It’s like an ice-cube.” And my dad’s like, “Don’t listen to your uncle Jeff, Mark. He’s coming back to be a happy little frog again.“

HM: Lastly, what’s in the horizon for Mark Bode?

MB: I have an 80-page Cobalt 60 story, ”The Death of Cobalt 60.” I have finished writing and penciling it. I am looking to finish it but I don’t have a publisher slated as of yet. Also, at the moment I have several fine art canvas prints in production from some of the work I did in issue 300 of HM by CYMK Gallery in Chicago.

Also, I see my father as a Tolkien or a Baum-type creator. Neither of those authors got to see their works on the big screen. I am hoping to beat the odds and see Dad's creations reach their full potential someday soon. A documentary on my father is being produced called THE BOOK OF VAUGHN by director Nick Francis. It’s been in the works for three years now. Nick has interviewed many artists and friends of Vaughn’s.

Mark's Web Site

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

An Interview with Mark Bodē by David Erwin

As a young boy, Mark grew up surrounded by a world of imaginary characters and places created and told to him by his father, Vaughn Bodē. As the son of a legendary artist whose influence has touched everything from cartoons to graffiti, Mark shares his memories in finding is own path, while carrying the responsibility of his father’s creations and art over the decades after his untimely death.

HEAVY METAL: You’ve been drawing since you were 3-years-old and published in Heavy Metal by the time you reached 15. Recently, you returned to Heavy Metal with new works. How do you feel about your return in Heavy Metal’s milestone issue #300?

MARK BODĒ: Dave, it’s an honor, it really is. So much has gone on and I’ve gone all over the world with our characters, comic cons, and art shows, mural events, movie premieres and during it all Heavy Metal was there and it’s amazing to be back in the saddle spinning some new stories for new followers in issue 300. It is the greatest American Science Fiction Fantasy Magazine of all time and I’m damn proud to be in it once again.

HM: Your first project for Heavy Metal was coloring your father, Vaughn’s, unfinished work "Zooks, the First Lizard in Orbit" – you were 15 years old at the time. How did this come about?

MB: Well, in 1978 I was attending The Art School in Oakland California. I was in 10th grade and wasn’t the best student to my teachers. I grew up around the best illustrators and painters in comics and pop culture. I must admit, I knew it and acted pretty cocky, as teens tend to do. People like Jeffery Catherine Jones, Bernie Wrightson, and Larry Todd - to name a few - were my uncles. There seemed nothing these art teachers could teach me that I did not know already. When at the time, Editor-in-Chief of Heavy Metal, Matty Simmons, asked if we had more Vaughn Bodē art for the magazine. My mother, Barbara, answered, "Yes, we have some black-and-white strips." Matty wanted colored art. It was then that Larry Todd, who had taken over mentoring my apprenticeship in art, suggested, "You color it, Mark." I was sure the project would get turned down if we pitched the idea. Vaughn’s 15-year-old son was to finish his father's work? So, it was decided I would ghost the project with Larry teaching me some tricks as I go. It worked and was printed a few months later. When I look now on those pages, they hold up very well. I can say, "Good job, kiddo" to my much younger self. That job and getting paid for it really gave me the confidence to follow in my fathers’ footsteps and to go pro and not look back. I must be still the youngest to work for HM. If there is another let me know.

HM: For #300 you’ve completed and added additional pages to his unfinished "SUNPOT, Dr. Electric Meets Da’ Repro Man" story. How did you come to choose Sunpot over other properties?

MB: Well, now that it's hundreds of issues later and I'm in my 50s, I can still find excitement to work and spin some new stories. When I was a teen, there were three properties that Larry Todd said I should expand on. The first being Cobalt 60. Larry suggested this first because Science Fiction is the wave of the future and Vaughn did not expand enough on that world, which is our radioactive future on Earth. Vaughn only did 20 pages of story and art for this property and suggested a cast of unused characters for a longer story that never panned out, 'til Larry and I turned it into a 500+ page epic. Second was Sunpot. Sunpot was an erotic sarcastic take on life in a chaotic and insane organic spaceship. Vaughn did a 30-page story broken up into chapters that ran in the pulp Sci Fi magazine Galaxy in the early '70s. My father wanted a better page rate from the editors and was turned down, even after the strip had increased the magazine's print run. So, Vaughn turned in his final installment, "SUNPOT is DEAD," where the entire crew hits a toxic gas cloud and dies. The magazine editors were speechless and the magazine tanked a few issues after Vaughn terminated working for them. The third property is Cheech Wizard, but I agreed with Larry that Cheech was too personal to Vaughn. I mean, Vaughn is Cheech Wizard, he is who is under the hat. So we should not continue that property... at least not for now.

HM: What was that like for you to revisit your father's characters after all these years?

MB: So, for 40 years I have been secretly yearning to expand on Sunpot. It has always been on a backburner wanting to come forth. When you and the staff approached me about some unpublished Vaughn work that could grace issue 300, I had a hard time finding stuff that was finished because Vaughn was always about getting in print. I was pawing through old college material of my Dad’s that was cool, but didn’t have the HM edge. I had a eureka moment, like Dad tapped me on the shoulder and whispered, "SUNPOT!!!" So, I dove into drawing up a short story and doing some pencils and here we are! Like old friends come back from the dead to get into trouble again. These characters are under my skin and all I gotta do is give them energy and they kind of start talking and threading their own stories. It has been pure joy and a way to spread the world of Bodē to a new group of readers.

HM: Your father left behind a huge universe of characters and worlds, just how big is that universe?

MB: Oh, unbelievably deep. I keep trying to organize it, I keep trying to delve into it every decade or so. A lot of it were drawn on whatever was around the house, garbage bags, laundry bags. Whatever he had, he would draw on. I would say thousands and thousands of characters are sitting there and could be added to or updated. His most prolific time, I would say was between 1958 and 1962, where he created thousands of worlds and characters, almost on a daily basis. He wouldn’t just doodle some character, he would create moons and planets and name them all. Then go into the planet and populate it with cities, towns, rivers, streams and name them. Then populate them with characters and let their stories unfold from there.

I don’t know how he did it. I know he ate a lot of Hostess Snowballs and Twinkies and coffee... a lot of coffee. And zoom around all our heads as if we were sitting still back in the caveman days. I mean, he was zooming and stay up for two days at a time just on the junk food and coffee.

HM: Did your father tell you stories with his characters?

MB: My childhood was filled with stories. I know at times Dad was testing new ideas on me at bedtime. The bear went over the mountain not to see what he could see, but to visit his pal Cheech. I looked forward to those stories. They had a basic structure that always went off in a bizarre and fantastical way by the time, "Good night, Mark" and the kiss on the head came. Every night my head was full.

HM: On the subject of revisiting your father’s characters, you’ve also written and illustrated a new short story based on Cobolt-60 that will be featured in Heavy Metal #302. What inspiration for this?

MB: Well, that was a bit of a departure from Cobalt’s normal world. As I was taught, "Don’t draw what you have to draw, always draw what you want to draw." I stared at the empty page and wanted to draw a zero-gravity sex scene with a Barbarella flair. "How’s that work?" I thought, "Hmmm, maybe I should get out some of my fears of this Covid anxiety my wife and family are experiencing." A dark, Covid-19-inspired short story unfolded. It’s a bit of a bummer, but hey, I had fun drawing it. Mission accomplished! (laughs)

HM: The first time I’d met you, I was a student at New York’s School of Visual Arts. You were signing your original comic book Miami Mice at a small, eclectic, hole-in-the-wall shop in Soho. Obviously, it’s a take on the television show Miami Vice, but can you tell us what compelled you to enter into the Indy comic book market?

MB: Sohozat! What a great store that was in the village I believe? I remember meeting you there for sure, I was glad somebody showed up! Thanks, Dave! (laughter)

Well, I also meet Henry Chalfant for the first time there, too, and Mare139... him and his brother, Kel, did massive top to bottom cars with Bodē characters in the early '80s into the '90s. Miami Mice was my first full-on comic book, outside of my father's worlds. It was a design I saw on carnival prizes and t-shirts. The Ninja Turtles had just begun selling out comics and hadn’t made it on TV yet. A black-and-white funny animal boom seemed to be taking hold of the comics scene. My wife, Molly, suggested that it would make a great comic book. I did some sketches of what I’d do with the parody and pitched the idea to Fred Todd of Rip Off Press, they did the Freak Brothers underground comic with Gilbert Shelton. They printed it on a whim and in one year’s time we sold 150,000 comics. Here it was my very first solo venture, I thought I had the golden touch. I ended the Mice in issue #4 with a TMNT and Cerebus crossover and went to another more interesting project... that did under a 2000 print run. Live and learn.

I ended up joining Kevin Eastman’s team of artists and we went onto have the time of our lives being on that wave. Yes, comics were very, very, good to me. The Internet changed all that, but damn... it was a hell of a ride!

HM: Would you go back to Miami Mice?

MB: (Laughter) It was bad! I was, "This is so not me." The over-the-top violence, the guns, and then in my studio, I had a mouse problem and mice were running over my feet while drawing it. I started taking my BB-gun and hiding under my drawing table waiting from them to come out of the walls... (laughter) I was, "It’s time to stop, Mark!"

HM: This is a side note, I recall when you were signing, your beautiful wife accompanied you or maybe she was still your girlfriend at the time, looking very much like a Bodē Broad. Has that ever crossed you mind? Tell me a little about Molly.

MB: Yes absolutely. When we met, she was a professional belly dancer. When I saw her dance at the Haight Street Fair in the late '70s, I said, "I must make her mine!" Love, infatuation, lust, the whole deal. I studied Arabic and Moroccan music to accompany her performances for many, many years, mostly on the west coast. She is my muse, my own personal Bodē Broad and I do not need to use models when I draw women... her looks, her hips, her prowess, is engrained into my DNA forever!

Molly also joined the Mirage Studios/Ninja Turtles team as an art-licensing assistant. She has been a huge help when anyone wants to license my images.

HM: I’d recently learned that you were also a student at SVA a few years before me, studying Fine Arts, also the same as me. What was your experience like attending there?

MB: I loved it. I was so honored to be accepted in there. I didn’t... I don’t think I got any scholarship or anything, but I was so excited. And I couldn’t believe Molly, my girlfriend at the time (who is now my wife), she lived in Brooklyn and we lived in San Francisco where we met. And she, out of love, moved back to Brooklyn even though she didn’t want to.

HM: I’m surprised you majored in Fine Arts when SVA has one of the best comic book departments.

MB: Well, I didn’t have a choice being a freshman. You had to take all the basics. And, I really wanted to be in Art Spiegelman’s class. There were certain people I was really looking forward to the next year. But we ended up moving back to San Francisco after two semesters, so I was just there for my basics. And I had Jack Potter. Does that ring a bell?

HM: No, I don’t know him.

MB: Well, he was a Yul-Brynner-type looking guy, and acted more arrogant than Yul Brynner. He would teach life drawing, “Five-minute pose, five-minute pose...” and you’re trying to keep up with his assignments. He’s like, “Change the pose, change the pose!” Then he’d walk around to see what everybody was doing... and he’d stop behind me, and a feeling of doom would happen – it wasn’t a good stop. I’d drawn a Bodē Broad of the woman sitting in the middle of the room. He was, “WHAT IS THAT?! Bubbly, cloudy drawing!” And I’m like, “It’s a Bodē Broad.” He ripped my drawing off the drawing board and tore it up! “DRAW AGAIN! USE YOUR EYES!” and I was, "Oh my God, I’m not going to survive this."

Another time, I was thinking about dropping my name just so I’d do better in the class. But at one point, he said, “One thing I despise are SONS AND DAUGHTERS OF ARTISTS! They’ve got this FIXATED WAY OF DRAWING AND THINKING! I’M GOING TO BREAK THEM DOWN!” Aaaah! I was so traumatized I didn’t say a damn thing after that. But he changed the way I think. He said, “Half of you will go onto BORING CAREERS! Look at me!” And then right outside there was a thunderstorm, “BA-LOOSH!” with lightning, and then he goes, “SEE!” (laughter)

But Spiegelman... I was actually working on "Yellow Hat." I was working for Archie Goodwin, and all my all my classmates were jealous because I was working for a major magazine, which wasn’t surprising because of who my Dad was... I didn’t give myself credit. I showed "Yellow Hat" to Spiegelman because I wanted to take his class and thought he would be like, “Yeah! Following your father, cool, go Mark,” but he didn’t say that, he said, “You got your father down, move on to your own stuff.” Huh? "How many have this circumstance?" That’s what I was thinking, "I have a legacy, my father died early, I need to continue this. This is important stuff." But he was totally the opposite. Obviously I’m not listening to him... I mean, he meant well. I might have gone a different course if I’d taken his class, because he wouldn’t have let me to fall into my comfortable space.

HM: At that time, in the early '80s New York City, graffiti was everywhere. Your father’s art and lettering style was embraced and appropriated by many of the early graffiti artists. Do you recall the first time you saw his art tagged on a train or building?

MB: Right. Well, it was after a day at Jack Potter’s class and probably being traumatized. I was schlepping my half-ass boring drawings (laughter) to the subway and going back to Brooklyn. I’m waiting at the West 23rd street station, went down there, I remember it like it was yesterday, and sittin’ there minding my own business and then a non-stop N train comes by me... and I saw a whole car of Dead Bone Mountain. It had Punkerpans, it had Cheech Wizard, it had Lizards, it had Bodē Broads, all on the train and the person’s name. It went by me and it was a eureka moment. But I didn’t... I thought it was one insane person, "It’s gotta be that some crazy person is out there in the yards spray painting my father’s stuff for no apparent reason." I think I mentioned it to my wife and then I put it behind me because I just figured it was a fluke and I’d never see it again. And I didn’t see it again, until I moved back to San Francisco a year later.

I noticed that above The Stud, which was a famous gay bar in San Francisco, was a PW-17 from "Zooks," which just a few years earlier I was coloring for Heavy Metal. And it was never in color before, right? So, you know it was from Heavy Metal. Then I thought, "Well then, it’s more than one person then. And after that I started, little by little, meeting new graffiti people in the Bay area. And they said, “Oh yeah, your Dad’s huge. Check this out, check that out.” And people down on the train tracks in Berkeley were doing an "Erotic” page or a panel. The woman in a meditative pose with her head exploding, that was huge, like ten-feet, fifteen-feet tall on the tracks. So, I started hanging out with various graffiti artists in the Bay area.

Then I met Dondi when I was visiting in Brooklyn. Dondi knew that my mother in-law had a bodega. She was the only woman at the time that was running her own bodega. And she’d hire goons to watch over the store, so she didn’t have to deal with getting mugged and stuff. She’d give them free beer and they would hangout and watch over Elsa. Dondi knew this, so he would frequent the bodega and say, “When’s Mark coming? When’s Mark coming again?” “Oh, he’s coming soon,” and then one day I show up and he was there. He showed me his books but he didn't tell me about spray painting or going to the yards, he never talked about any of it. He wanted to know, “What was Vaughn like? What did he eat? How did he work?” He was a mega fan, and he was drawing these graffiti pieces that were beyond me. I was strictly a comic artist at that point.

HM: When did you pick up your first can of spray paint?

MB: It never crossed my mind when I was at School of Visual Arts. I just wasn’t thinking about it, I was just so wrapped up in trying to continue my father’s work. So, when I went back and I started hanging out with these graffiti artists that were doing my father’s characters, I realized this is what’s up. And so they gave me cans - but I sucked! It was like working with a club. It’s like, “Here’s a pencil... now here’s a club, try to draw with that.” And so I would try to do what they were doing, but I just swept it under the rug as a failure on my part. But the annoyance of people getting so good at it kept me trying. (laughter) "You’re so good at drawing Cheech Wizard, I gotta be able to do that!" How did they control that?

It was because Krylon and Rust-Oleum was all you had back then, it was scraps, you know? And the pressure of the cans was just immense. I didn’t know any tricks, and my friends... I don’t think those people were helping me, they didn’t want me to be too good (chuckle), “Let him struggle.” So, the can control was just out of my hands, I just couldn’t... until this one day, I actually tried to do it in public.

And that was done in Oakland, at the Piano Warehouse, 8th and Pine. My friend, Steve Heck, who was one of the original guys from the “Burning Man” days when it first started, he used to build bars out of grand pianos out in the desert and torch it. He said, “Hey, you know these graffiti guys, huh? Invite them over to paint, they can paint inside of the warehouse.” So I did and I was super green, but I had some good teachers there that kinda helped me – I couldn’t even sign my name right. I didn’t have the chops, but that first piece that I did ended up in Spraycan Art and Jim Prigoff suggested that I take a picture in front of it. I didn’t realize the importance of it, I just thought it was this guy who wanted something for his portfolio.

HM: That must have launched a whole new career for you?

MB: It did. I still sucked for a long time. But I got good at it. Especially once low-pressure cans came in along with multiple caps. Then I picked it up again and it was like painting with an airbrush. I was so happy, and I started excelling in it fairly quickly.

HM: I remember walking on 8th street in the Greenwich Village and seeing your name in a gallery space along with your dad’s. It was The Psychedelic Solution Gallery, which was focused primarily on psychedelic art and 1960s concert posters. How did that come about?