MALCOLM McDOWELL Interview

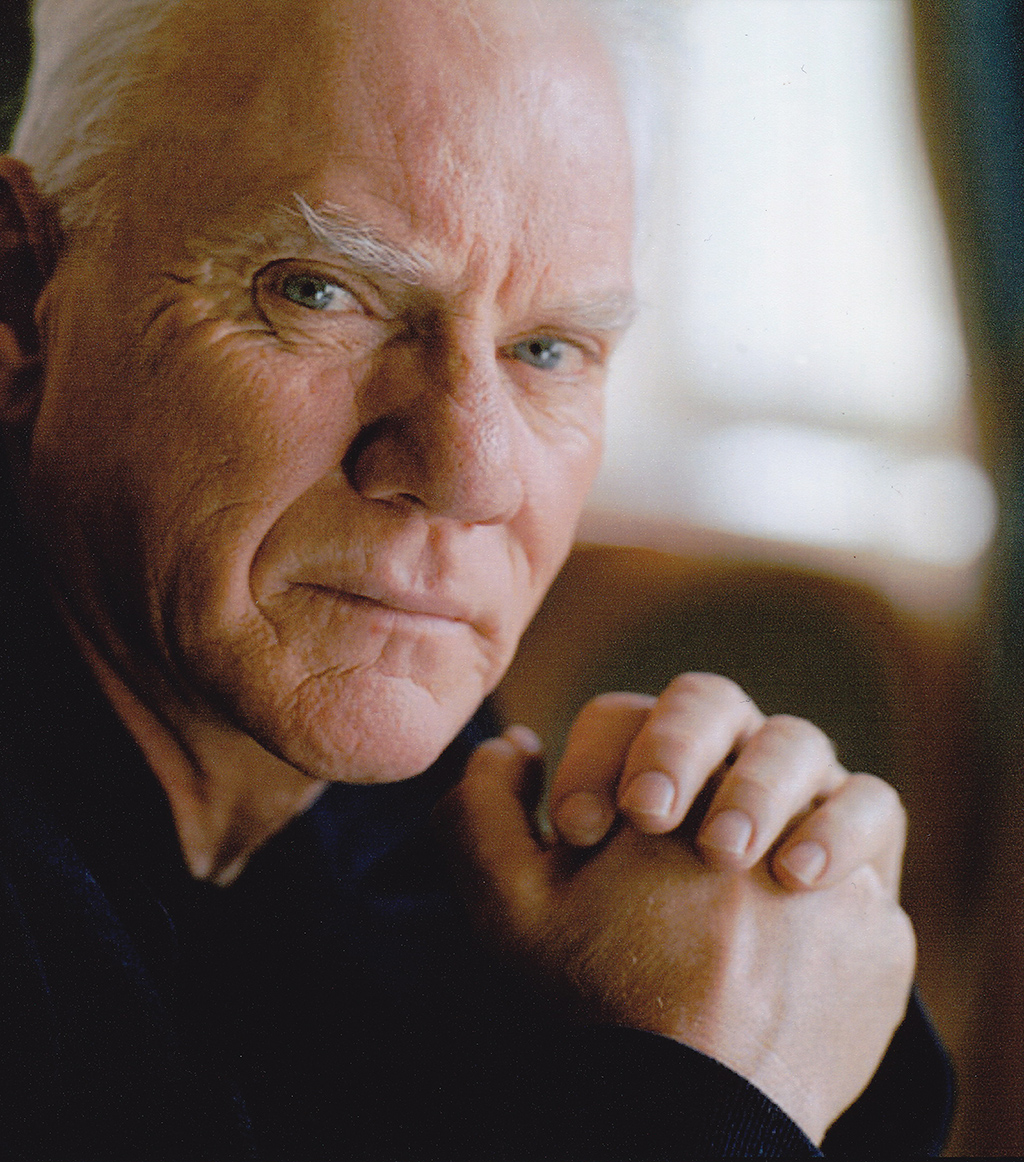

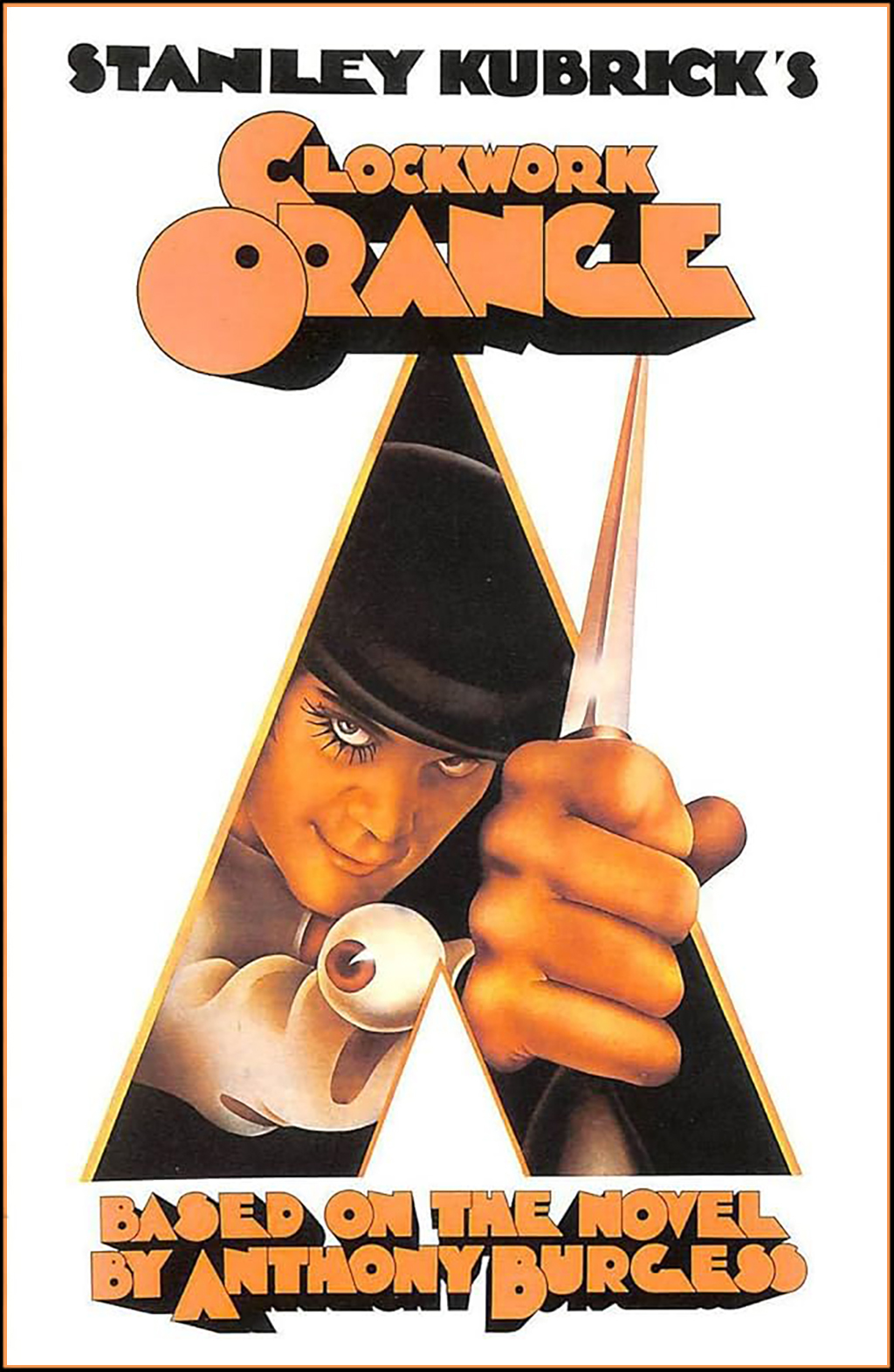

Is Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange the most incendiary science fiction film of the 20th Century, or merely the most infamous? Malcolm McDowell himself isn’t quite sure how to untangle the legacy of the lurid 1971 masterpiece that made him an international star, but he’s astounded by the simple fact that people are still asking him to try.

“It’s an amazing thing to have a movie that’s celebrated fifty years after its premiere,” McDowell says in the recently released inaugural episode of Geoff Boucher’s Mindspace, the podcast from Heavy Metal and DIGA Studios.

In the far-ranging interview, the Yorkshire native touched on other notable roles in an acting career that spans six different decades and includes more than 300 screen credits, among them Time After Time, The Artist, Cat People, and two Halloween films. McDowell, then 77, had shown a flair for the diabolical by memorably portraying scoundrels, crooks, madmen, and tyrants. The list includes Caligula and Rupert Murdoch, as well as Tolian Soran, the 24th Century rogue who offed Starfleet legend James T. Kirk.

There’s no doubt, however, about the signature role of McDowell’s filmography. Kubrick had spotted the actor’s screen debut in Lindsey Anderson’s If... (1968) and thought McDowell would work as the lead role in his next project.

Kubrick had just made film history with the cosmic riddles of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but his planned follow-up was a decidedly different vision of the future. Kubrick’s ninth feature film would be a scabby and subversive tale of juvenile delinquency and fractured lives in a futuristic London. Instead of an interstellar quest for next-level in-sights this Kubrick film would frame humanity as a vicious race to the bottom of our baser instincts.

The central character caught in the societal gears of Clockwork is the callous youngster named Alex DeLong, who was first introduced as a symbol of brutal youth in the pages of Clockwork’s source material: the 1962 name-sake novel written by Anthony Burgess. As Alex, McDowell would portray the bad seed at the rotten center of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

Astonishingly, Alex is supposed to be a mere 15 years old at the start of the film’s story. McDowell (who was 27 when he filmed the movie) shrugs off the disconnect by pointing out the fact that the script was never a document written in stone.

”It’s interesting that Kubrick really wasn’t that concerned with script. He wanted great characters, of course, and a good story. But script? That wasn’t his forte. Even though he takes credit on Clockwork for the script, which is a bit of a joke, I mean, there was nobody else around that did it. He actually cribbed it from the book and then took a lot of input from me... that was a film that was a real collaboration because I came up with chunks of it.”

One of those chunks would become a cornerstone moment in A Clockwork Orange and a screen moment that continues to echo as new generations find the film. The production had ground to a halt during a pivotal scene where Alex and his cohorts invade a home and terrorize the occupants. The problem that vexed Kubrick was how to give the sequence the stylized distance from reality that would keep the moment rooted in the “otherness” of the world presented in the feature.

“And we had nothing. We had nothing. It went back to being a sort of realistic movie: thugs come in, throw bottles through the window, terrorize, beat up the guy and leave. Very traditional. Seen it a million times, seen it on the telly a million times. I think we had just come off shooting the very end of the movie so that we were very high because the end really works. The end is, is I think, fabulous. And it’s hard to get a good ending in a movie. I mean, often you’ll find there are four ends or three ends or two or something, but this was just perfect. And so then when we started shooting the home invasion, as they call it now, it was really hard to find the style in which to do it. That was the problem. Everything else had a style. And we had no style for that.”

It was McDowell who launched into song with “Singin’ in the Rain,” the feel-good classic that was as sunny as the Gene Kelly musical of the same name. It was the key that unlocked the scene.

McDowell set the stage for Boucher, “By the fifth day, I was getting a little bored of this. I was like, ‘Let’s go to work.’ So when he passed me, I was sitting on the steps in the living room that went down to the dining area or something. As he passed me, he just said, ‘Can you dance?’ And I jumped up and said, ‘Can I dance?’ And went straight in and literally ad libbed the whole thing to ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ with the smacks, the kicks and all. Well, I saw him laughing so hard he stuck his handkerchief in his mouth.”

McDowell wasn’t sure how his antennae picked up the song’s faint signal in his subconscious. “It was automatic. I didn’t even think of it. It was just, you know, the character was euphoric. That’s the most euphoric song I know. It just came out.”

McDowell, with a wry smile added, “To take something so sweet and innocent and beautiful as ‘Singing in the Rain’ and to use it in such a dastardly way is actually very funny. I am someone with a really warped sense of humor. I admit it. But, Stanley thought so, too. So we both had this sort of black sense of humor and we both thought it was bloody funny, you know?”

That inspired bit of subversion led to an awkward and unexpected encounter between McDowell and Kelly, the Hollywood song and dance legend. Check out the podcast for the surprising reason for Kelly giving McDowell the cold shoulder during that stateside meeting in the 1970s.

“An overlooked aspect of the legacy of A Clockwork Orange is that it’s intended as black comedy, which the perverse musical number should attest to,” McDowell says. Black comedy or not, the film endures with a tenacity that few of its generational screen contemporaries have shown (although 1971 was a robust year for introducing maverick screen characters with traction: Willie Wonka, Dirty Harry Callahan, John Shaft, and Popeye Doyle all arrived on the silver screen that year.)

McDowell and the late Kubrick didn’t part ways well. One sore subject was payment for the narrator work he did in a recording studio setting. McDowell is able to distance himself from the contentiousness of the disagreement to recognize the accomplishment that the unpaid labor yielded.

The dark, dystopian visions of A Clockwork Orange earned it an X-rating in the United States, but those visions also secured four Oscar nominations for the Warner Bros. release, including best picture, best director and best adapted screenplay.

The movie’s legacy was complicated further in 1973 when Kubrick himself withdrew the film’s U.K. distribution, which effectively made it illegal to screen the feature in Britain for more than 25 years. The filmmaker made that choice amid the feverish press coverage of two high-profile violent criminal cases with suspects who purportedly invoked the film’s imagery (in one instance by the way they were dressed, in the other instance by what they sang).

If the anniversary was to take the film to Cannes, McDowell planned tobe there to drink it all in, perhaps with a glass of milk. He had also decided to make a to toast Kubrick who, he said, would have been outraged by the site and all that goes with its aura.

“The joke is the film would never have been entered at the Cannes Film Festival, it would never have won a prize,” McDowell said. “And Kubrick hated the idea of being judged by these sorts of semi-intellectuals, you know. French critics or whatever. He loathed it. So that’s sort of amusing just in itself.”

MALCOLM McDOWELL Interview

Is Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange the most incendiary science fiction film of the 20th Century, or merely the most infamous? Malcolm McDowell himself isn’t quite sure how to untangle the legacy of the lurid 1971 masterpiece that made him an international star, but he’s astounded by the simple fact that people are still asking him to try.

“It’s an amazing thing to have a movie that’s celebrated fifty years after its premiere,” McDowell says in the recently released inaugural episode of Geoff Boucher’s Mindspace, the podcast from Heavy Metal and DIGA Studios.

In the far-ranging interview, the Yorkshire native touched on other notable roles in an acting career that spans six different decades and includes more than 300 screen credits, among them Time After Time, The Artist, Cat People, and two Halloween films. McDowell, then 77, had shown a flair for the diabolical by memorably portraying scoundrels, crooks, madmen, and tyrants. The list includes Caligula and Rupert Murdoch, as well as Tolian Soran, the 24th Century rogue who offed Starfleet legend James T. Kirk.

There’s no doubt, however, about the signature role of McDowell’s filmography. Kubrick had spotted the actor’s screen debut in Lindsey Anderson’s If... (1968) and thought McDowell would work as the lead role in his next project.

Kubrick had just made film history with the cosmic riddles of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but his planned follow-up was a decidedly different vision of the future. Kubrick’s ninth feature film would be a scabby and subversive tale of juvenile delinquency and fractured lives in a futuristic London. Instead of an interstellar quest for next-level in-sights this Kubrick film would frame humanity as a vicious race to the bottom of our baser instincts.

The central character caught in the societal gears of Clockwork is the callous youngster named Alex DeLong, who was first introduced as a symbol of brutal youth in the pages of Clockwork’s source material: the 1962 name-sake novel written by Anthony Burgess. As Alex, McDowell would portray the bad seed at the rotten center of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

Astonishingly, Alex is supposed to be a mere 15 years old at the start of the film’s story. McDowell (who was 27 when he filmed the movie) shrugs off the disconnect by pointing out the fact that the script was never a document written in stone.

”It’s interesting that Kubrick really wasn’t that concerned with script. He wanted great characters, of course, and a good story. But script? That wasn’t his forte. Even though he takes credit on Clockwork for the script, which is a bit of a joke, I mean, there was nobody else around that did it. He actually cribbed it from the book and then took a lot of input from me... that was a film that was a real collaboration because I came up with chunks of it.”

One of those chunks would become a cornerstone moment in A Clockwork Orange and a screen moment that continues to echo as new generations find the film. The production had ground to a halt during a pivotal scene where Alex and his cohorts invade a home and terrorize the occupants. The problem that vexed Kubrick was how to give the sequence the stylized distance from reality that would keep the moment rooted in the “otherness” of the world presented in the feature.

“And we had nothing. We had nothing. It went back to being a sort of realistic movie: thugs come in, throw bottles through the window, terrorize, beat up the guy and leave. Very traditional. Seen it a million times, seen it on the telly a million times. I think we had just come off shooting the very end of the movie so that we were very high because the end really works. The end is, is I think, fabulous. And it’s hard to get a good ending in a movie. I mean, often you’ll find there are four ends or three ends or two or something, but this was just perfect. And so then when we started shooting the home invasion, as they call it now, it was really hard to find the style in which to do it. That was the problem. Everything else had a style. And we had no style for that.”

It was McDowell who launched into song with “Singin’ in the Rain,” the feel-good classic that was as sunny as the Gene Kelly musical of the same name. It was the key that unlocked the scene.

McDowell set the stage for Boucher, “By the fifth day, I was getting a little bored of this. I was like, ‘Let’s go to work.’ So when he passed me, I was sitting on the steps in the living room that went down to the dining area or something. As he passed me, he just said, ‘Can you dance?’ And I jumped up and said, ‘Can I dance?’ And went straight in and literally ad libbed the whole thing to ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ with the smacks, the kicks and all. Well, I saw him laughing so hard he stuck his handkerchief in his mouth.”

McDowell wasn’t sure how his antennae picked up the song’s faint signal in his subconscious. “It was automatic. I didn’t even think of it. It was just, you know, the character was euphoric. That’s the most euphoric song I know. It just came out.”

McDowell, with a wry smile added, “To take something so sweet and innocent and beautiful as ‘Singing in the Rain’ and to use it in such a dastardly way is actually very funny. I am someone with a really warped sense of humor. I admit it. But, Stanley thought so, too. So we both had this sort of black sense of humor and we both thought it was bloody funny, you know?”

That inspired bit of subversion led to an awkward and unexpected encounter between McDowell and Kelly, the Hollywood song and dance legend. Check out the podcast for the surprising reason for Kelly giving McDowell the cold shoulder during that stateside meeting in the 1970s.

“An overlooked aspect of the legacy of A Clockwork Orange is that it’s intended as black comedy, which the perverse musical number should attest to,” McDowell says. Black comedy or not, the film endures with a tenacity that few of its generational screen contemporaries have shown (although 1971 was a robust year for introducing maverick screen characters with traction: Willie Wonka, Dirty Harry Callahan, John Shaft, and Popeye Doyle all arrived on the silver screen that year.)

McDowell and the late Kubrick didn’t part ways well. One sore subject was payment for the narrator work he did in a recording studio setting. McDowell is able to distance himself from the contentiousness of the disagreement to recognize the accomplishment that the unpaid labor yielded.

The dark, dystopian visions of A Clockwork Orange earned it an X-rating in the United States, but those visions also secured four Oscar nominations for the Warner Bros. release, including best picture, best director and best adapted screenplay.

The movie’s legacy was complicated further in 1973 when Kubrick himself withdrew the film’s U.K. distribution, which effectively made it illegal to screen the feature in Britain for more than 25 years. The filmmaker made that choice amid the feverish press coverage of two high-profile violent criminal cases with suspects who purportedly invoked the film’s imagery (in one instance by the way they were dressed, in the other instance by what they sang).

If the anniversary was to take the film to Cannes, McDowell planned tobe there to drink it all in, perhaps with a glass of milk. He had also decided to make a to toast Kubrick who, he said, would have been outraged by the site and all that goes with its aura.

“The joke is the film would never have been entered at the Cannes Film Festival, it would never have won a prize,” McDowell said. “And Kubrick hated the idea of being judged by these sorts of semi-intellectuals, you know. French critics or whatever. He loathed it. So that’s sort of amusing just in itself.”

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

Is Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange the most incendiary science fiction film of the 20th Century, or merely the most infamous? Malcolm McDowell himself isn’t quite sure how to untangle the legacy of the lurid 1971 masterpiece that made him an international star, but he’s astounded by the simple fact that people are still asking him to try.

“It’s an amazing thing to have a movie that’s celebrated fifty years after its premiere,” McDowell says in the recently released inaugural episode of Geoff Boucher’s Mindspace, the podcast from Heavy Metal and DIGA Studios.

In the far-ranging interview, the Yorkshire native touched on other notable roles in an acting career that spans six different decades and includes more than 300 screen credits, among them Time After Time, The Artist, Cat People, and two Halloween films. McDowell, then 77, had shown a flair for the diabolical by memorably portraying scoundrels, crooks, madmen, and tyrants. The list includes Caligula and Rupert Murdoch, as well as Tolian Soran, the 24th Century rogue who offed Starfleet legend James T. Kirk.

There’s no doubt, however, about the signature role of McDowell’s filmography. Kubrick had spotted the actor’s screen debut in Lindsey Anderson’s If... (1968) and thought McDowell would work as the lead role in his next project.

Kubrick had just made film history with the cosmic riddles of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but his planned follow-up was a decidedly different vision of the future. Kubrick’s ninth feature film would be a scabby and subversive tale of juvenile delinquency and fractured lives in a futuristic London. Instead of an interstellar quest for next-level in-sights this Kubrick film would frame humanity as a vicious race to the bottom of our baser instincts.

The central character caught in the societal gears of Clockwork is the callous youngster named Alex DeLong, who was first introduced as a symbol of brutal youth in the pages of Clockwork’s source material: the 1962 name-sake novel written by Anthony Burgess. As Alex, McDowell would portray the bad seed at the rotten center of Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange.

Astonishingly, Alex is supposed to be a mere 15 years old at the start of the film’s story. McDowell (who was 27 when he filmed the movie) shrugs off the disconnect by pointing out the fact that the script was never a document written in stone.

”It’s interesting that Kubrick really wasn’t that concerned with script. He wanted great characters, of course, and a good story. But script? That wasn’t his forte. Even though he takes credit on Clockwork for the script, which is a bit of a joke, I mean, there was nobody else around that did it. He actually cribbed it from the book and then took a lot of input from me... that was a film that was a real collaboration because I came up with chunks of it.”

One of those chunks would become a cornerstone moment in A Clockwork Orange and a screen moment that continues to echo as new generations find the film. The production had ground to a halt during a pivotal scene where Alex and his cohorts invade a home and terrorize the occupants. The problem that vexed Kubrick was how to give the sequence the stylized distance from reality that would keep the moment rooted in the “otherness” of the world presented in the feature.

“And we had nothing. We had nothing. It went back to being a sort of realistic movie: thugs come in, throw bottles through the window, terrorize, beat up the guy and leave. Very traditional. Seen it a million times, seen it on the telly a million times. I think we had just come off shooting the very end of the movie so that we were very high because the end really works. The end is, is I think, fabulous. And it’s hard to get a good ending in a movie. I mean, often you’ll find there are four ends or three ends or two or something, but this was just perfect. And so then when we started shooting the home invasion, as they call it now, it was really hard to find the style in which to do it. That was the problem. Everything else had a style. And we had no style for that.”

It was McDowell who launched into song with “Singin’ in the Rain,” the feel-good classic that was as sunny as the Gene Kelly musical of the same name. It was the key that unlocked the scene.

McDowell set the stage for Boucher, “By the fifth day, I was getting a little bored of this. I was like, ‘Let’s go to work.’ So when he passed me, I was sitting on the steps in the living room that went down to the dining area or something. As he passed me, he just said, ‘Can you dance?’ And I jumped up and said, ‘Can I dance?’ And went straight in and literally ad libbed the whole thing to ‘Singin’ in the Rain’ with the smacks, the kicks and all. Well, I saw him laughing so hard he stuck his handkerchief in his mouth.”

McDowell wasn’t sure how his antennae picked up the song’s faint signal in his subconscious. “It was automatic. I didn’t even think of it. It was just, you know, the character was euphoric. That’s the most euphoric song I know. It just came out.”

McDowell, with a wry smile added, “To take something so sweet and innocent and beautiful as ‘Singing in the Rain’ and to use it in such a dastardly way is actually very funny. I am someone with a really warped sense of humor. I admit it. But, Stanley thought so, too. So we both had this sort of black sense of humor and we both thought it was bloody funny, you know?”

That inspired bit of subversion led to an awkward and unexpected encounter between McDowell and Kelly, the Hollywood song and dance legend. Check out the podcast for the surprising reason for Kelly giving McDowell the cold shoulder during that stateside meeting in the 1970s.

“An overlooked aspect of the legacy of A Clockwork Orange is that it’s intended as black comedy, which the perverse musical number should attest to,” McDowell says. Black comedy or not, the film endures with a tenacity that few of its generational screen contemporaries have shown (although 1971 was a robust year for introducing maverick screen characters with traction: Willie Wonka, Dirty Harry Callahan, John Shaft, and Popeye Doyle all arrived on the silver screen that year.)

McDowell and the late Kubrick didn’t part ways well. One sore subject was payment for the narrator work he did in a recording studio setting. McDowell is able to distance himself from the contentiousness of the disagreement to recognize the accomplishment that the unpaid labor yielded.

The dark, dystopian visions of A Clockwork Orange earned it an X-rating in the United States, but those visions also secured four Oscar nominations for the Warner Bros. release, including best picture, best director and best adapted screenplay.

The movie’s legacy was complicated further in 1973 when Kubrick himself withdrew the film’s U.K. distribution, which effectively made it illegal to screen the feature in Britain for more than 25 years. The filmmaker made that choice amid the feverish press coverage of two high-profile violent criminal cases with suspects who purportedly invoked the film’s imagery (in one instance by the way they were dressed, in the other instance by what they sang).

If the anniversary was to take the film to Cannes, McDowell planned tobe there to drink it all in, perhaps with a glass of milk. He had also decided to make a to toast Kubrick who, he said, would have been outraged by the site and all that goes with its aura.

“The joke is the film would never have been entered at the Cannes Film Festival, it would never have won a prize,” McDowell said. “And Kubrick hated the idea of being judged by these sorts of semi-intellectuals, you know. French critics or whatever. He loathed it. So that’s sort of amusing just in itself.”