HM Time Machine: STEPHEN KING Interview from 1980

Interview by BHOB

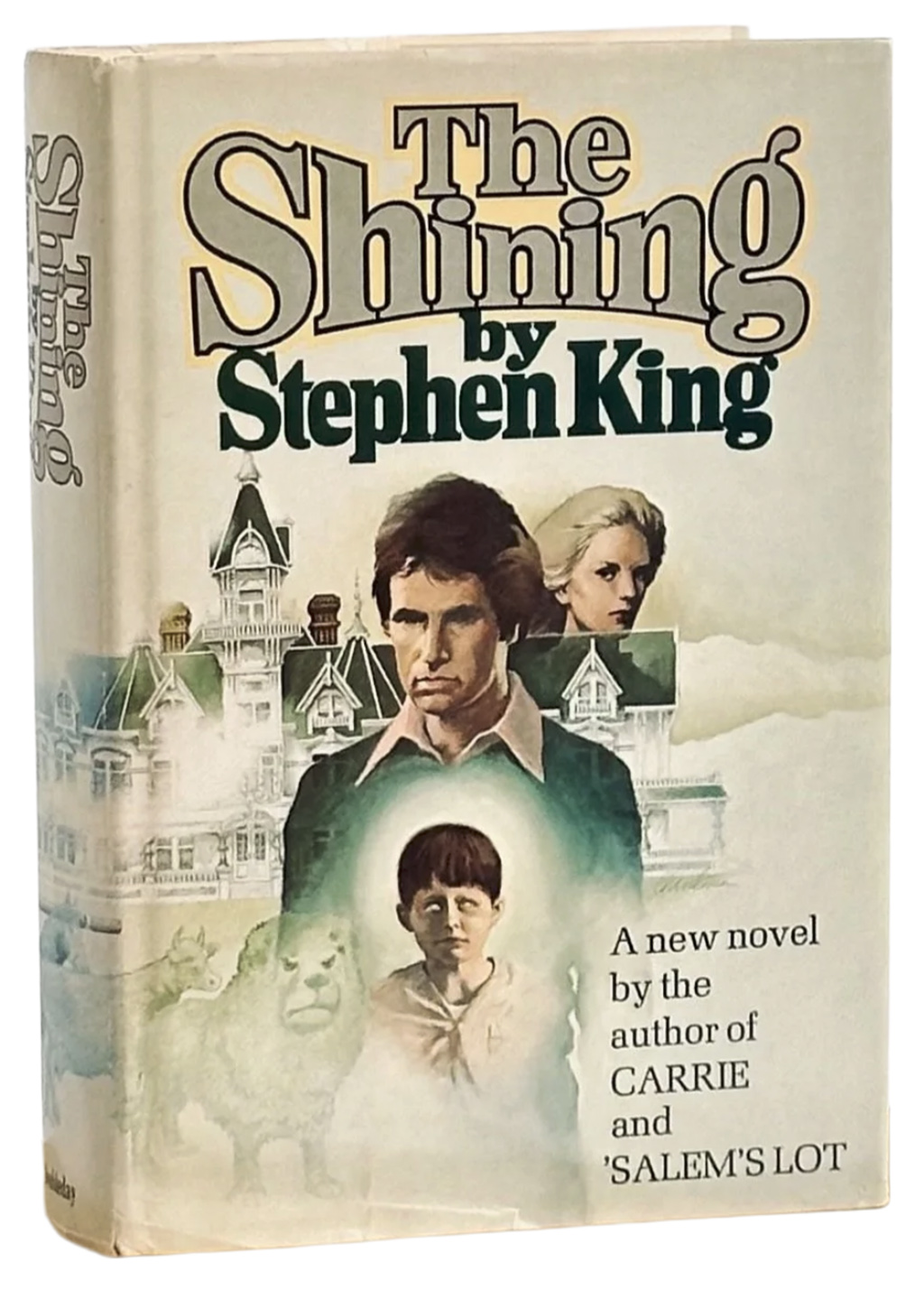

When Stanley Kubrick's film version of The Shining is unveiled a few months from now, it may be hailed as the greatest horror film of the century. It seems that Kubrick, not content with escalating the art of the science fiction film in 2001, long had a secret desire "to make the world's scariest movie." And he knew he had latched onto the right property when he read Stephen King's novel The Shining, about a five year old whose psychic powers trigger supernatural forces at a bizarro Colorado hotel, where he's snowbound with his mother and alcoholic father.

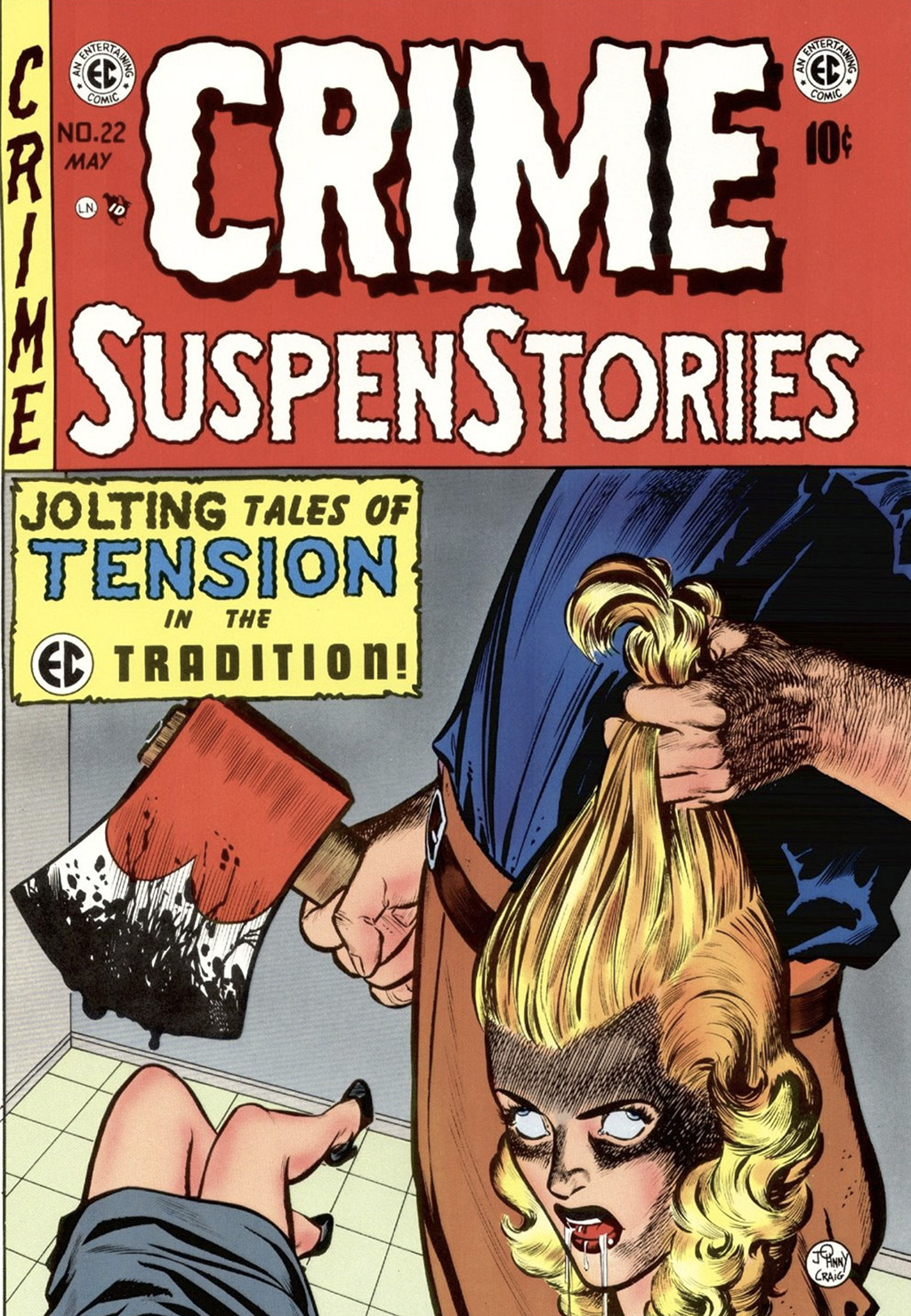

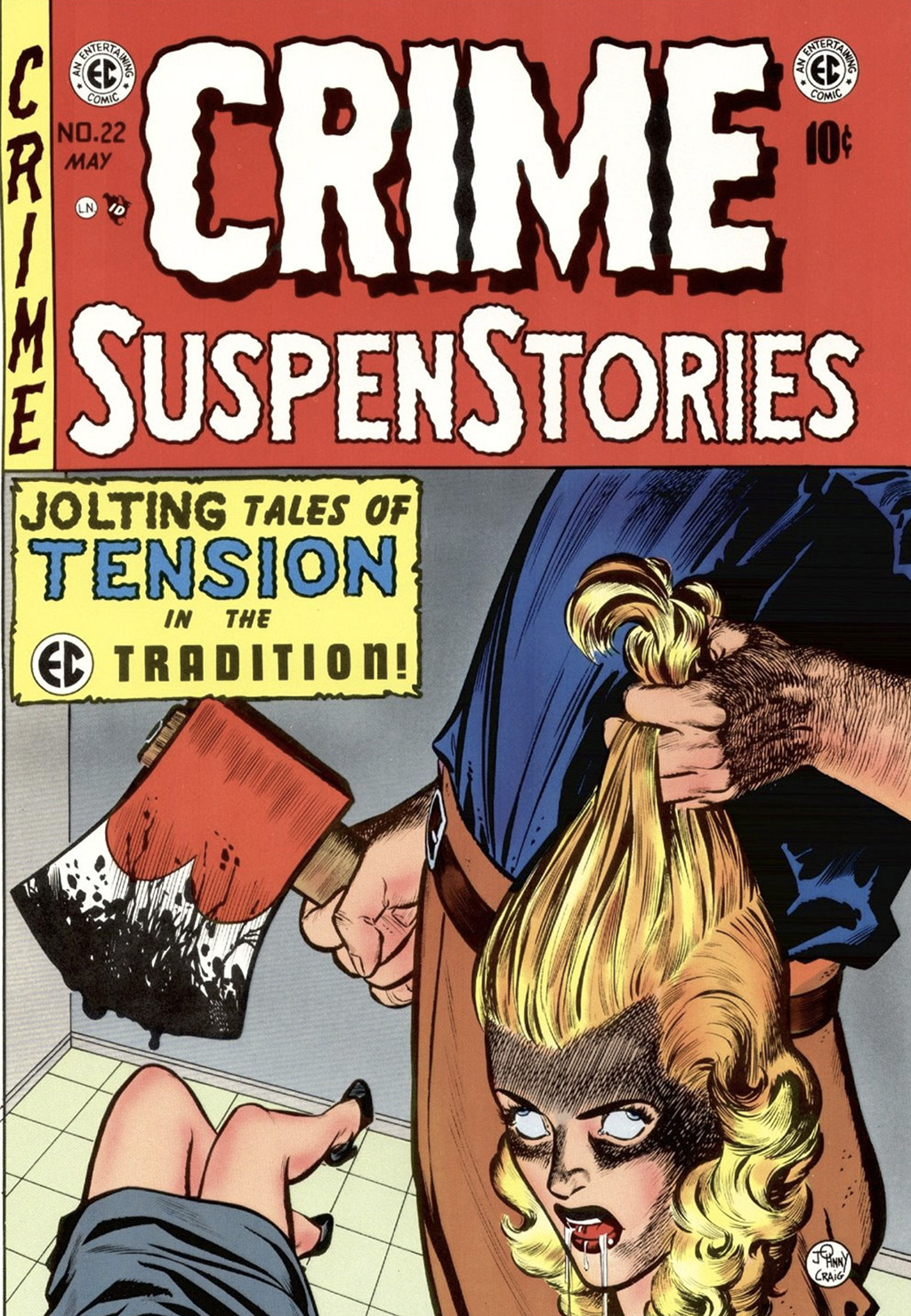

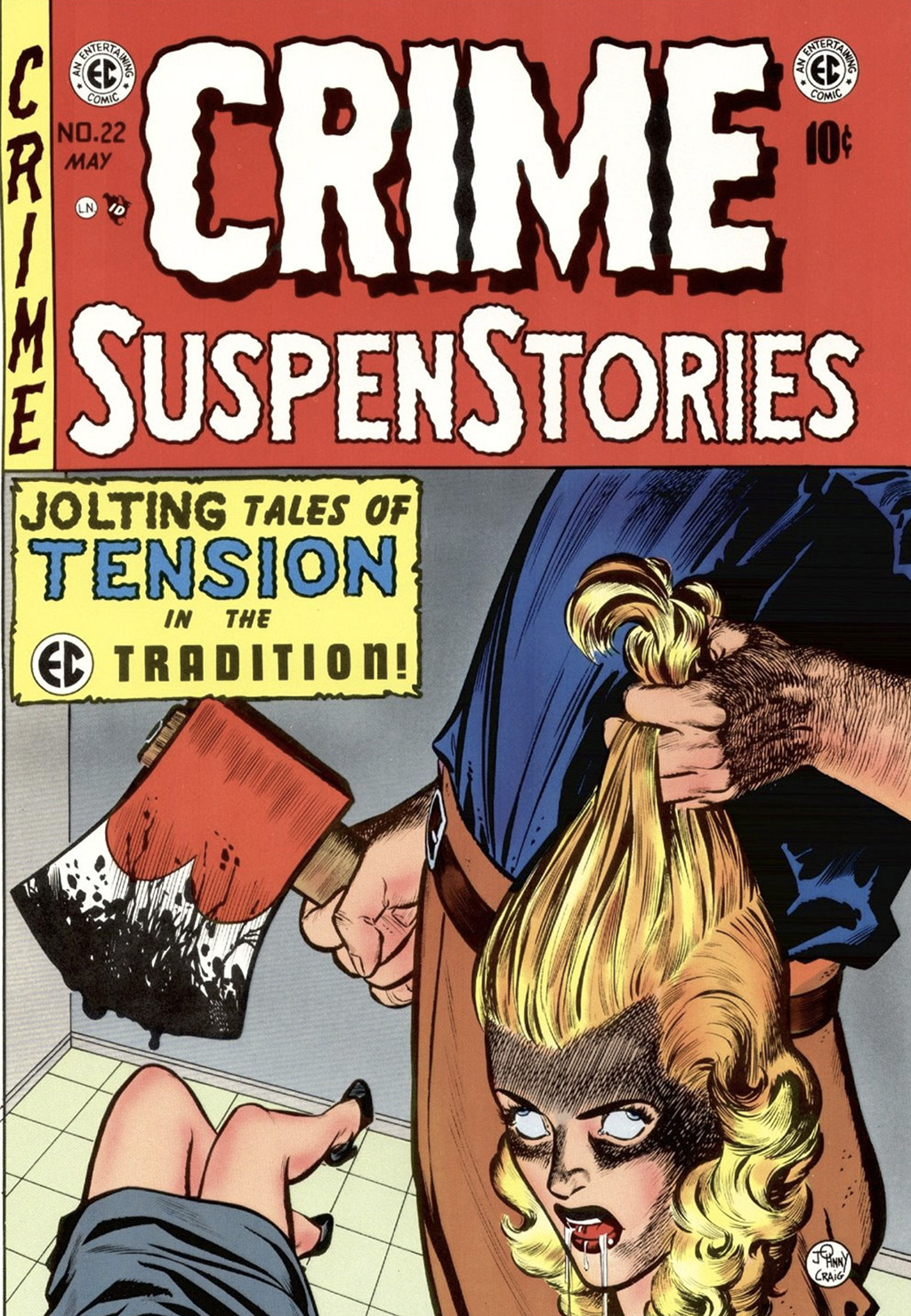

Stephen King grew up in the pale phosphor video-glow of the "Million Dollar Movie's" SF horrors, endlessly repeated. He was nurtured on a diet of the Big Three - Bradbury, Bloch, and Lovecraft, authors of The Guidebook to Anywhat. He devoured Fate magazine and the panels of dark pageantry in EC comics, that eruption of freaks, zombies, ghouls, and crazies whose doom wails shattered the still nights of the complacent fifties. He worked in a knitting mill and a laundromat, went to the University of Maine, and lived in "a crummy trailer" while teaching school. Today he is the world’s best-selling author of horror fiction. The kid who watched the "Million Dollar Movie" now writes million dollar novels: his current contract is $2.5 million for three books.

After carving a batch of EC-influenced short stories out of his typewriter for Cavalier and other publications, he created the telekinetic Carrie, staked out Salem’s Lot with vampires, and then decided to move his fiction out of New England: The Shining came into being when he combined a Colorado vacation with his quest for a fresh story setting. ("Nothing was coming" is the way he put it.) In Colorado it was suggested to King and his wife, Tabitha, that they stay at Estes Park’s famous Stanley Hotel (where Johnny Ringo was supposedly gunned down). They arrived at the end of the tourist season, the day before Halloween, and checked into the totally deserted resort hotel. As the only guests, they ate that evening in the abandoned dining hall, surrounded by chairs upended on tables covered with plastic sheets, while a tuxedo-clad band played a shadow waltz to the empty room. "I stayed at the bar afterward and had a few beers," King told interviewer Mel Allen. "Tabby went upstairs to read. When I went up later, I got lost. It was just a warren of corridors and doorways — with everything shut tight and dark and the wind howling outside. The carpet was ominous with jungly things woven into a black and gold background. There were these old-fashioned fire extinguishers along the walls that were thick and serpentine. I thought. 'There's got to be a story in here somewhere.'"

If you’ve read The Shining and had your mind squeegeed down the maddening halls of the book’s Overlook Hotel, then you already know that King found one helluva story there. That’s his talent: he takes a mundane, commonplace setting, adds familiar, even overworked themes, and introduces characters that outwardly seem just like people you or I might have known — but then comes King’s twisting high dive straight into the souls of these characters, a plunge of such force and intensity that he scrapes the bottom of their psychological depths before finally surfacing with whatever new book. There may be digressions and multilayers of atmospheric detail, but his storytelling is so simple and direct, there’s never a wasted word. It’s terse, thumbscrew tight, and it zips along like the calculated construction of an EC story where each drawing is a progression toward the payoff punch, the shocker in the last panel. He followed The Stand, a huge novel about a “superflu” apocalypse now, with The Dead Zone, a best-seller about a schoolteacher who emerges from a four-year coma and finds he has the ability to see a person's past and future when he touches them.

After publication, come the critics. Like this Christopher Lehmann-Haupt dude at the New York Times; he ends a rave review with this bringdown nonsense: "When I finished The Dead Zone, I found myself replaying the story in my mind the way one does after having seen a particularly compelling movie. That may not say very much for its qualities as literary art. But it's meant to tell you that the book is very strong as entertainment." C'mon, Chris! It says a great deal for literary art, and you know it! After heaping extolments right ("wonderful specificity) and left ("ominous and nerve-wracking unpredictability"). Lehmann-Haupt suddenly seems to remember that, after all, he is writing for the Times; he reverts to type (cold type, at that) and shovels his praise over with the dung of an outdated academic lit-crit argument. Of course King's prose is art! Zappa? Art! Moebius? Art! Graffiti? Art! (One wall of NYC graffiti reads, "Graffiti is an art, and if art is a crime, let God forgive us all.") Anyone raised on EC knows how art and entertainment can be the same.

The fact is that King is simply jotting down the movies he sees in his head. This explains why Lehmann-Haupt experienced afterimages, and it also explains why almost every King novel or short story either has been or will be up there on the shiver screen. This nightmare parade began with Brian De Palma's Carrie (1976), and now Salem's Lot is a 1979-80 CBS-TV mini-series directed by Tobe Hooper (director of the 1974 Texas Chainsaw Massacre). Stirling Silliphant is the executive producer for this four-hour Salem's Lot (to air on two successive nights) shot from a script by Paul Monash, the producer of Carrie and Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five (1972). Location filming took place in southern California last summer with a cast featuring David Soul, Bonnie Bedelia, James Mason, Lance Kerwin, Reggie Nalder, Marie Windsor, and Elisha Cook.

In addition to an original screenplay about a haunted, automated Maine radio station, King also has on hand another script, Children of the Corn, which he adapted from one of his Night Shift short stories: and he is adapting some of his uncollected stories, including "The Crate" for a George Romero film, The Creep Show. Milton Subotsky. the man who filmed EC in Tales from the Crypt (1972) and Vault of Horror (1973), has optioned six stories from Night Shift, enough to make not one, but two anthology movies: The Revolt of the Machines (Trucks," "The Mangler." "The Lawnmower Man") and Night Shift ("The Ledge," "Quitters, Inc.," "Sometimes They Come Back"). And in the fall of 1980, Everest House will publish King's Danse Macabre, an informal, nonfiction glance at the past thirty years of the horror genre in comics, movies, radio, and TV.

So maybe you only read comics and go to the movies, and you sit there sipping your cream-of-nowhere-soup and you ask me, "Okay, look, Bhob, they're gonna make movies and TV shows out of all his stuff anyway - so why should I read all these books? Gosh! They look pretty thick!" and I can say to you only: There is no movie like reading King, which is more like standing in a dream you know is a dream and crying while you watch the ripped-out, razor-slashed pages of your precious EC collection caught by the wind to flutter down the Main Street of Thomton Wilder's Our Town, Grover's Corners, New Hampshire, where these fading fifties fear sketches go skittering down the gutter past a white picket fence, coming to rest against the claws and mud-crusted fur of a thing you knew existed when you were four years old, and even if such an amalgamative Wilder/EC/Lovecraft impossiblility could happen, there is not, and never will be, such a movie, okay? The macabre, King's fiction tells us, lurks in the ordinary, waiting and beckoning. It's there. Even in a blade of grass.

Beckoning.

Ever see a Jacobsen lawnmower? Waiting on a park bench to talk with Stephen King. I stared at one, an armada of vicious whirling blades that could make you into people-sauce if it decided to come at you. I thought I heard the grass scream, realized I was entering the domain of the King, and crossed the street for the following interview.

Bhob: What is the origin of the phrase "the shining" as a description of psychic power?

King: The origin of that was a song by John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band called "Instant Karma." The refrain went "We all shine on." I really liked that, and used it. The name of the book originally was The Shine, and somebody said, "You can't use that because it's a pejorative word for black." Since nobody likes to have a joke played on themselves, I said, "Okay, let's change it. What'll we change it to?" They said, "How about The Shining?" I said. "It sounds kind of awkward." But they said, "It gets the point across, and we won't have to make any major changes in the book." So we did, and it became The Shining instead of The Shine.

Bhob: Who is the writer who worked on The Shining screenplay with Kubrick?

King: Diane Johnson. She did a novel called The Shadow Knows. She's just published another one this year. She's a good writer. She writes reviews for the New York Times Book Review sometimes; she had one not too long ago on a book of letters by or about William Butler Yeats. Quite a smart lady.

Bhob: What is the title of the haunted radio station screenplay?

King: It doesn't have a title. I think the perfect title would be something that had four letters, but I can't think of a good word - like "W-something" - that would be creepy. Jesus, it's a wonderful idea!

Bhob: Oh, you mean a title made out of the call letters of the radio station - like Robert Stone's WUSA?

King: Yeah. Like that! Like that! Only I'd like to be able to do something-

Bhob: Ah, like "WEIR."

King: Yeah. "WEIR." That would be real good. Yeah. It's based on this automated radio station. They go completely automatic. They have these big, long drums of tape that do everything. They punch in the time. They make donuts for the announcer who comes in to give the weather. But mostly, it's just this, "Aren't you glad you tuned in WEIR?... Hi! This is WEIR, you fucking son of a bitch. You're going to die tonight." Irony like that in a syrupy voice.

Bhob: And is someone interested in this right now?

King: I've got to finish it. I'm not trying to do anything with it except finish it. I take it out every once in a while and tinker it up, but I don't really seem to have the kicker yet. There's no real urge to push it through, there's no excitement there just yet. I've got the idea, I just can't seem to hook it up.

Bhob: In Night Shift the EC influence is most apparent, yet you were very young when EC was on the newsstands during the early fifties, right?

King: I used to get some comics. I don't think they were ECs, but I used to buy them with the covers torn off. There was always somebody being chopped up and spitted on barbecue grills or buried alive. My guess is the comics predated 1955. I would have bought them, say, in the period 1958 to 1960. But they might have been sitting in some guy's warehouse.

Bhob: When did you first become conscious of EC?

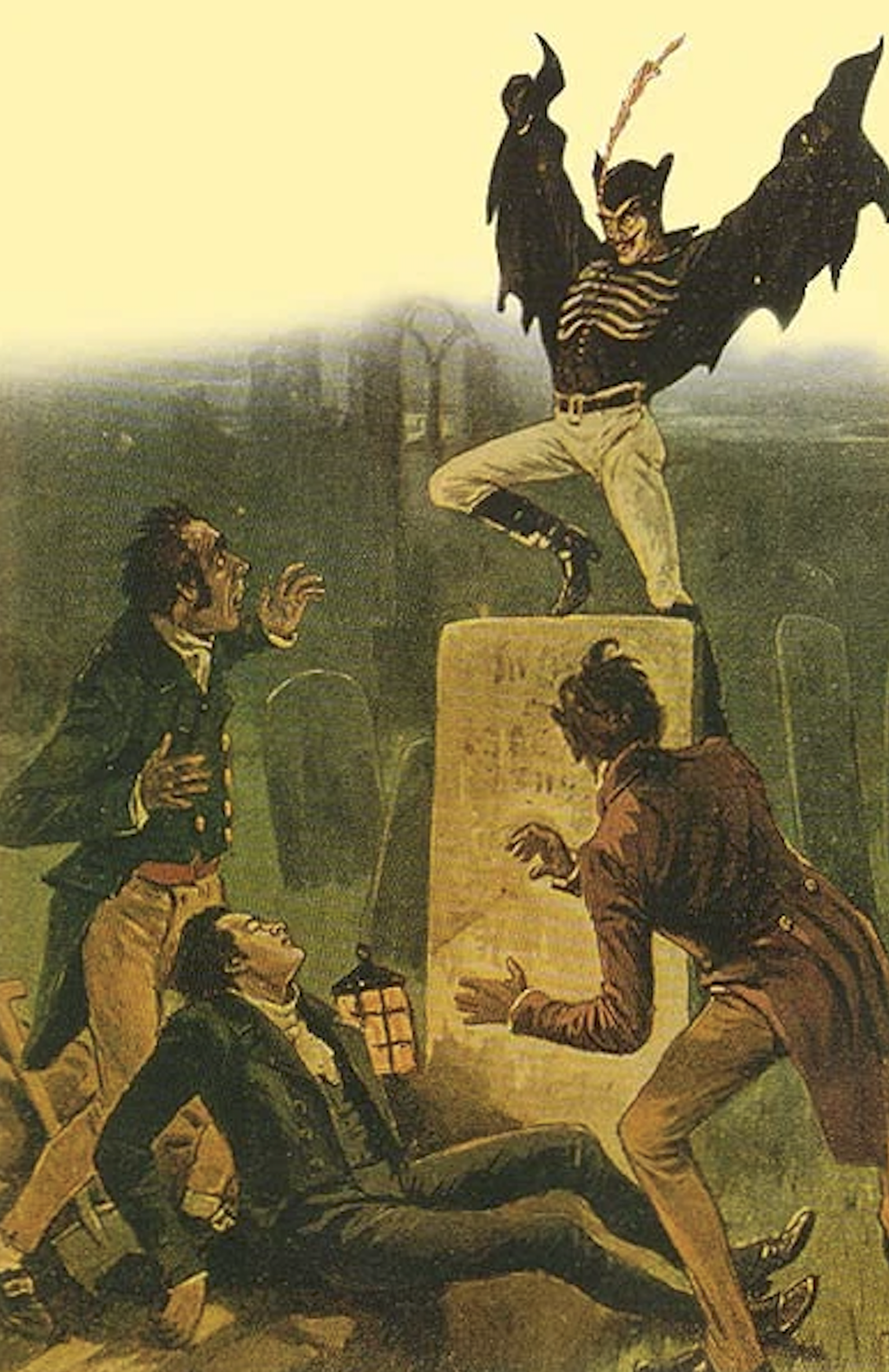

King: I think we must have swapped the magazines around when I was younger. I can't really say when I became conscious of it. People would talk about them, and if you saw some of these things, you'd pick them up - even if it cost a buck. At that time you might have been able to get three for a buck, now they cost a lot more than that. When EC started to produce supernatural tales, they did it after the worst holocaust that people had ever known - World War II and the death of six million Jews and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. All at once, Lovecraft, baroque horrors, and the M.R. James's ghost that you'd hear about secondhand from some guy in his club began to seem a little bit too tame. People began to talk about more physical horrors - the undead, the thing that comes out of the grave. I still remember one of these stories where this guy is killed by his cheating wife and her boyfriend, and he comes out of the grave. He's all rotted, and he's staggering through the street, saying. "I'm coming, Selena, but I have to go slowly because pieces of me keep falling off."

Bhob: What's the idea behind The Creep Show?

King: The Creep Show is supposed to be a comic book motif like those Subotsky films Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror. Neither George Romero nor I felt the Subotsky films worked very well. We'd like to do five or six or seven pieces, short ones, that would just build up to the punch, wham the viewer, and then you'd go on to the next one. Somewhere there would be a body that would come out of the ground and chase people around.

Bhob: When you were a kid, did you read Castle of Frankenstein?

King: Yes, yes. I had about seven or eight issues in sequence, and I don't know what's become of them. For every fan, that's an old sad song, but I had them all. It was, by far, the best of any of the monster magazines. I think, probably like most of us, I came to Famous Monsters of Filmland first. I just sort of discovered that poking off of a drugstore rack one day, and I was a freak for it, every issue. I couldn't wait for it to come out. And then when Castle of Frankenstein came out, I saw an entirely different level to this: really responsible film criticism. The thing that really impressed me about it was how small the print was. You know, they were really cramming: there was a lot of written material in there. The pictures were really secondary.

Bhob: I was the editor.

King: Were you really? No shit? Really? Doubly nice to meet you! Castle of Frankenstein was so thick, so meaty, that you could really read it for a week... you could. I used to read it from cover to cover, and I can't imagine I was alone in that. There was a wonderful book column in it that would talk about Russell Kirk (Old House of Fear, Surly Sullen Bell) and other people, and just go on and on. There was that wonderful project where all the movies were going to be catalogued, all the horror movies of all time.

Bhob: We never got past the letter "R" in that alphabetical listing. You credit films as a source for your writing, but how can this apply to syntax and style? And what's an example of how you might have translated film grammar into fiction?

King: The best example of that was The Shining probably. The framework of The Shining was supposed to be a Shakespearean tragedy. If you look at the book, it has five sections, originally these were labeled Act I, Act II, and on through to Act V, and each act was divided into scenes. The editor came to me when the book was done and said, "This seems a little bit pretentious. Would you consider dividing it into parts and chapters?" I said, "Yeah, if you want me to. I will,” and I did. But it was a useful device to me because it limited scenes. In each case, each chapter, a limited scene in one place - and each scene was in a different place, until near the very end, where it really becomes a movie, and you go outside for the part where Hallorann is coming across the country on his snowmobile. Then you can almost see the camera traveling along beside him. You learn syntax and you learn grammar through your reading, and you don't really study it. It just kind of sets in your mind after a while because you've read enough. Even now, if you gave me a sentence with a subordinate clause, I'm not sure I could diagram it on paper, but I could tell you whether or not it was correct because that's the mindset that I have. But to visualize so strong: as a kid in Connecticut I watched the “Million Dollar Movie" over and over again. You begin to see things as you write-in a frame like a movie screen.

I don't really care what the characters look like - Johnny Smith in The Dead Zone, or Jack Torrance. I didn't think that Jack Nicholson was right for that part, but not for any way that he looks - just because he seemed a little bit old to a degree. Although I can't always see what the characters look like. I always know my right from my left in any scene, and I know how far it is to the door and to the windows and how far apart the windows are and the depth of field. The way that you would see it in a film, in The Blue Dahlia or something like that.

Bhob: If you visualize this with sharp focus and depth of field, then why do you say you don't know what they look like?

King: What they look like isn't terribly important to me. It doesn't have to be John Wayne in True Grit. It doesn't have to be Boris Karloff as Frankenstein's monster. It doesn't matter to me. Some actors are better than others: I thought Lugosi was terrible as Dracula; he was all right until he opened his mouth, and then I just dissolved into gales of laughter.

Bhob: As you write, do you ever slip into the styles of different directors?

King: No, no. Very rarely do I ever think of anything like that. One of the strange things that happened to me was I got beaten in the Sunday New York Times on The Shining. I got a really terrible review of The Shining, accusing me of cribbing from foreign suspense films. I think one of them was Knife in the Water, and one of them was Diabolique.

Bhob: Because of the body in the bathtub?

King: Yes. What was so funny about the criticism was that by God, I live in Maine! The only foreign films we get are like Swedish sex films. I've never seen Diabolique. I've never seen any of those pictures. If I came up with them, it was just that there are so many things you can do in the field. Its movements are as stylized as the movements of a dance. You've got your gothic story somewhere in the gothic castle with a clank of chains in the night. In The Shining, instead of a gothic castle. you have a gothic hotel, and instead of chains rattling in the basement, the elevator goes up and down - which is another kind of rattling chain.

When Sissy Spacek was announced as the lead of Carrie, a lot of people said to me, "Don't you think that's dreadful miscasting?" Because in the book, Carrie is presented as this chunky, solid, beefy girl with a pudding-plain face who is transformed at the prom into being pretty. I didn't give a shit what she looked like as long as she could look sort of ugly before and then look nice at the prom. She could have had brown hair or red hair or anything, and it didn't really matter who - because I didn't have a very clear picture. But I had a clear picture of her heart. I think. And that's important to me. I want to know what my characters feel and what makes them move.

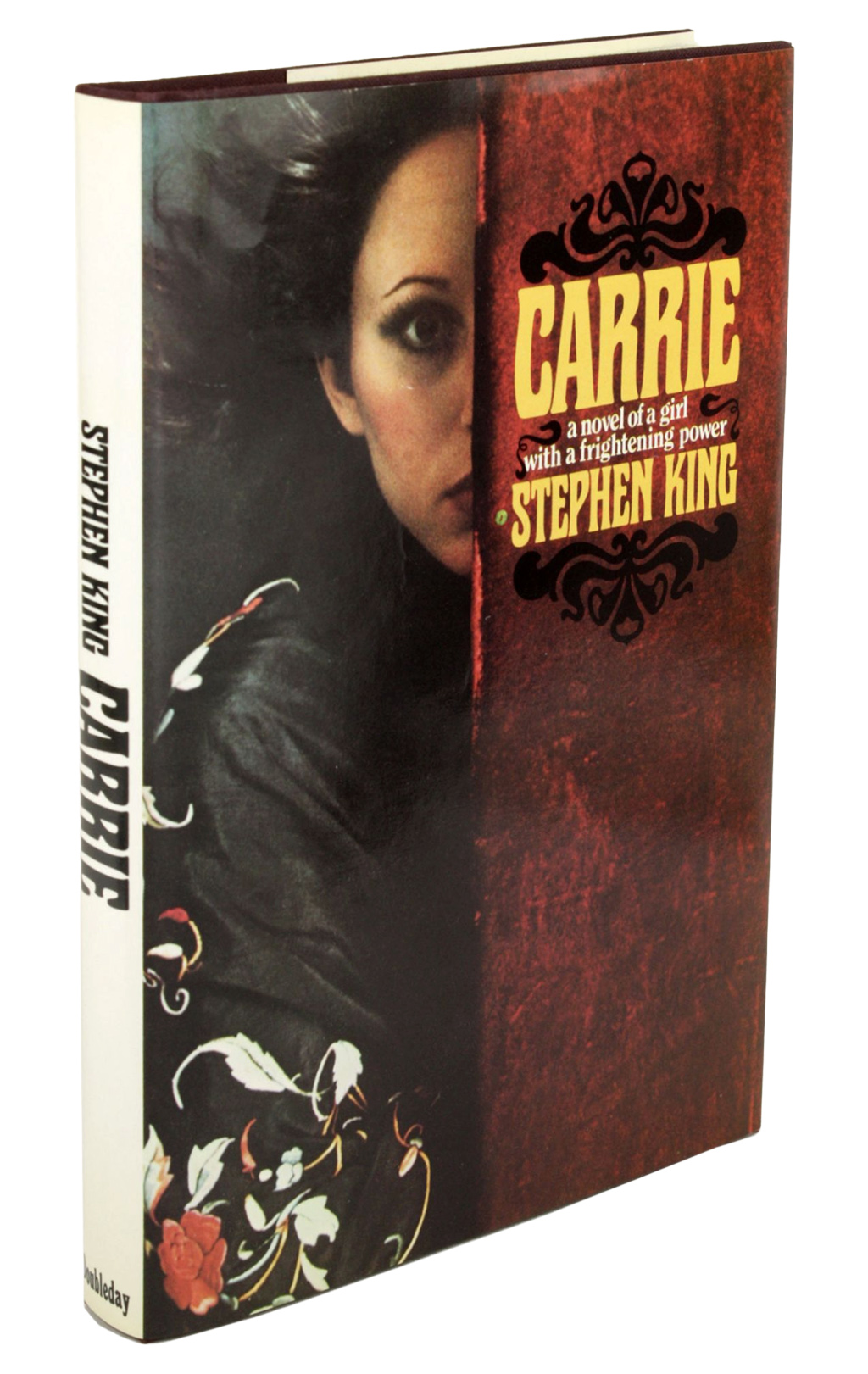

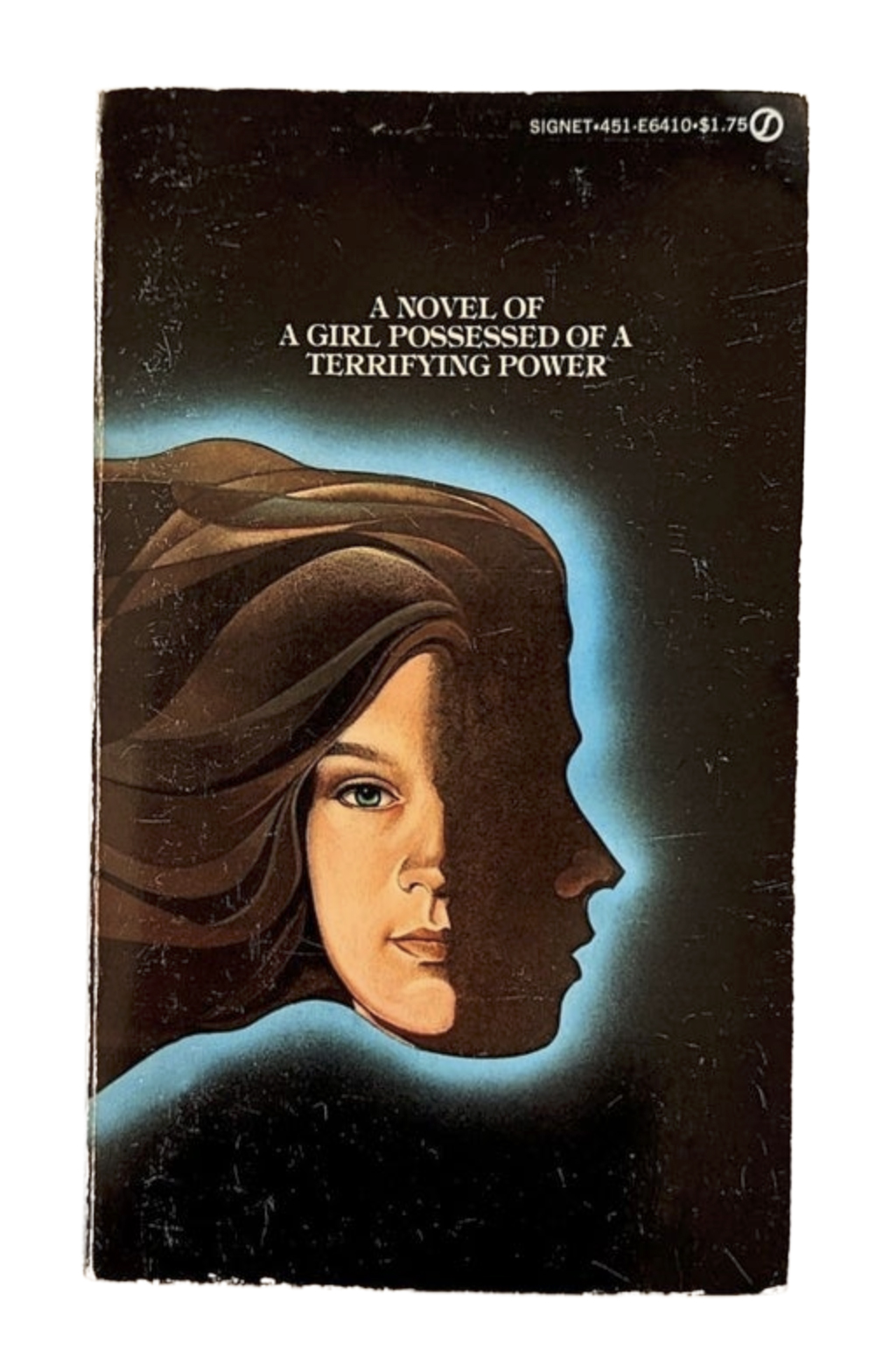

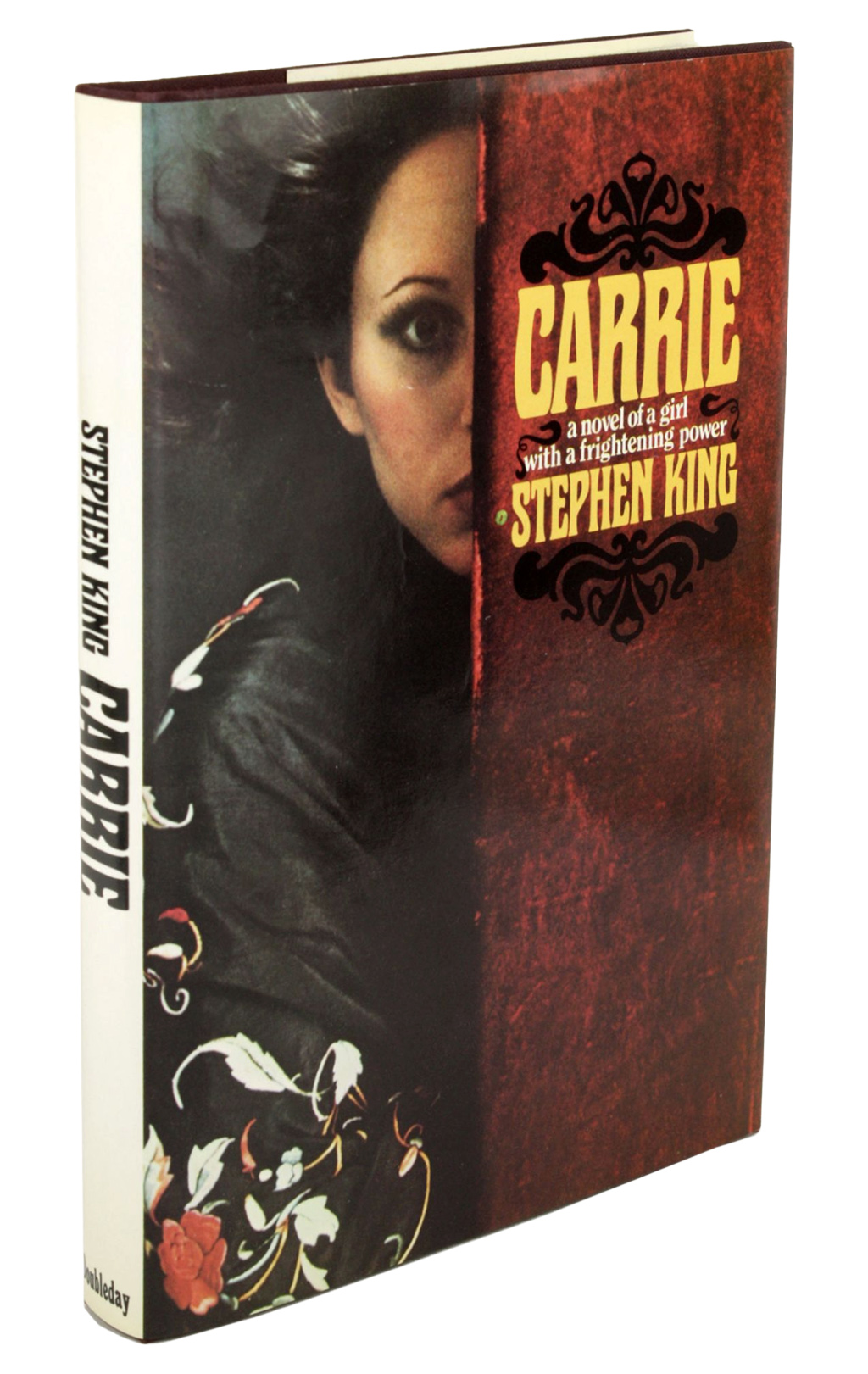

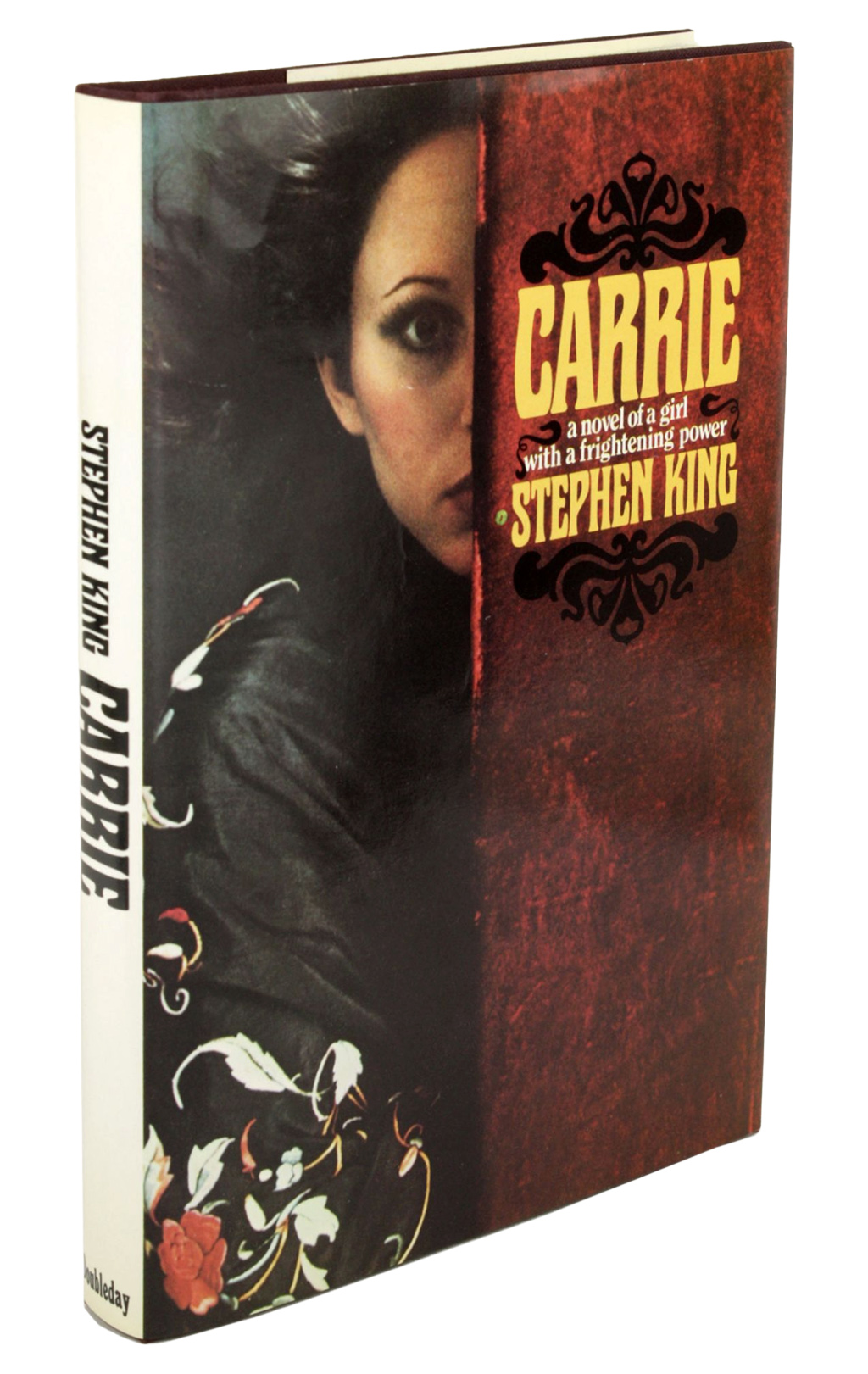

Bhob: The jacket on the hardback Carrie has nothing to do with the book.

King: Yes. Well, it doesn't. My editor and I had a concept on that, but of course, one of the things about Bill Thompson, my editor, was that he was a man with relatively little power at Doubleday, and it kept showing up in funny little ways. When I left Doubleday, they canned him. It was kind of like a tantrum: "We'll kill the messenger that brought the bad news."

Our concept of the jacket would have been a Grandma Moses-type primitive painting of a New England village that would have gone around in a wrap to the back. But the jacket was done by Alex Gotfryd, who does have a lot of power at Doubleday. What he gave us was a photograph of a New York model who looks like a New York model. She doesn't even look like a teenager.

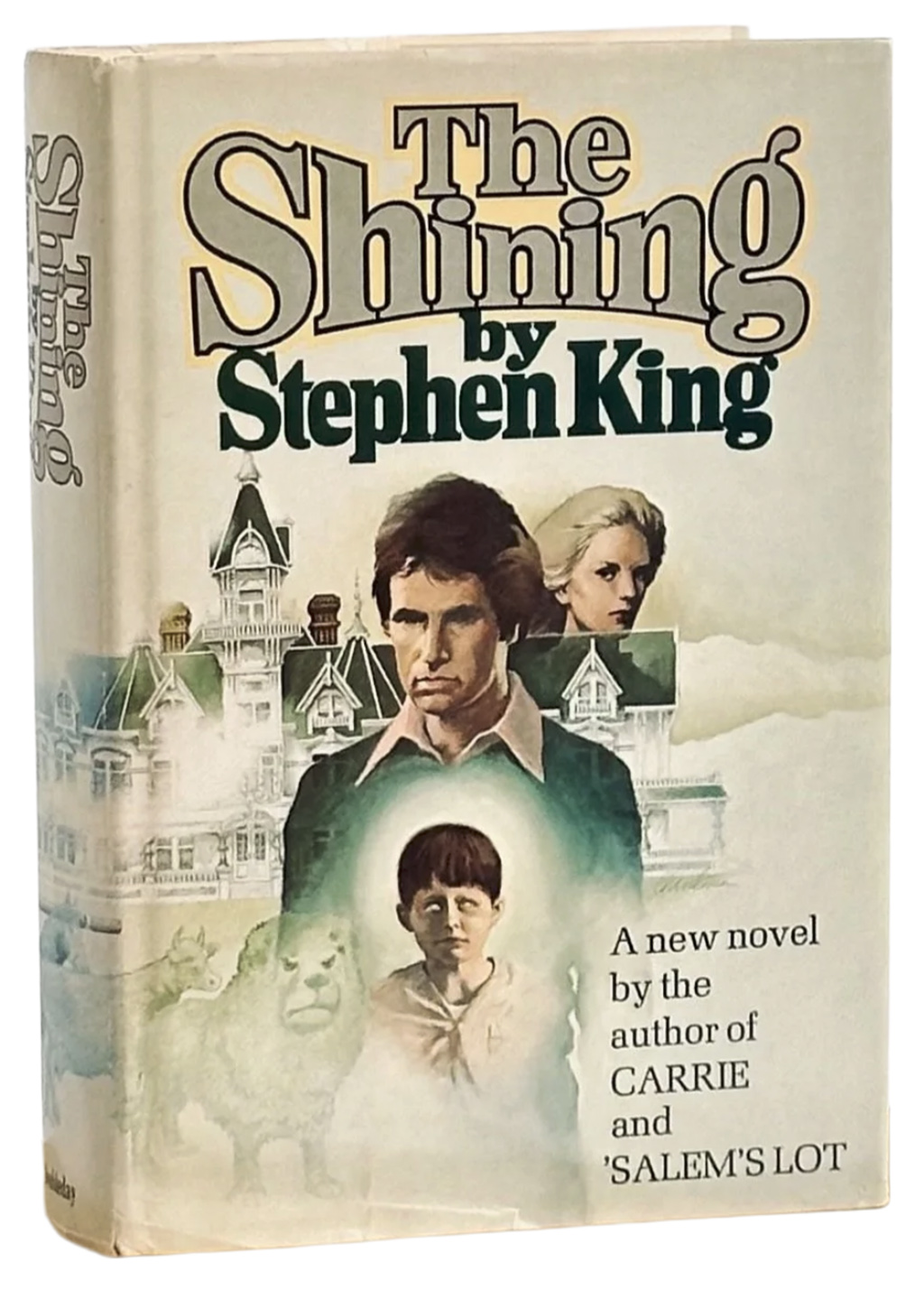

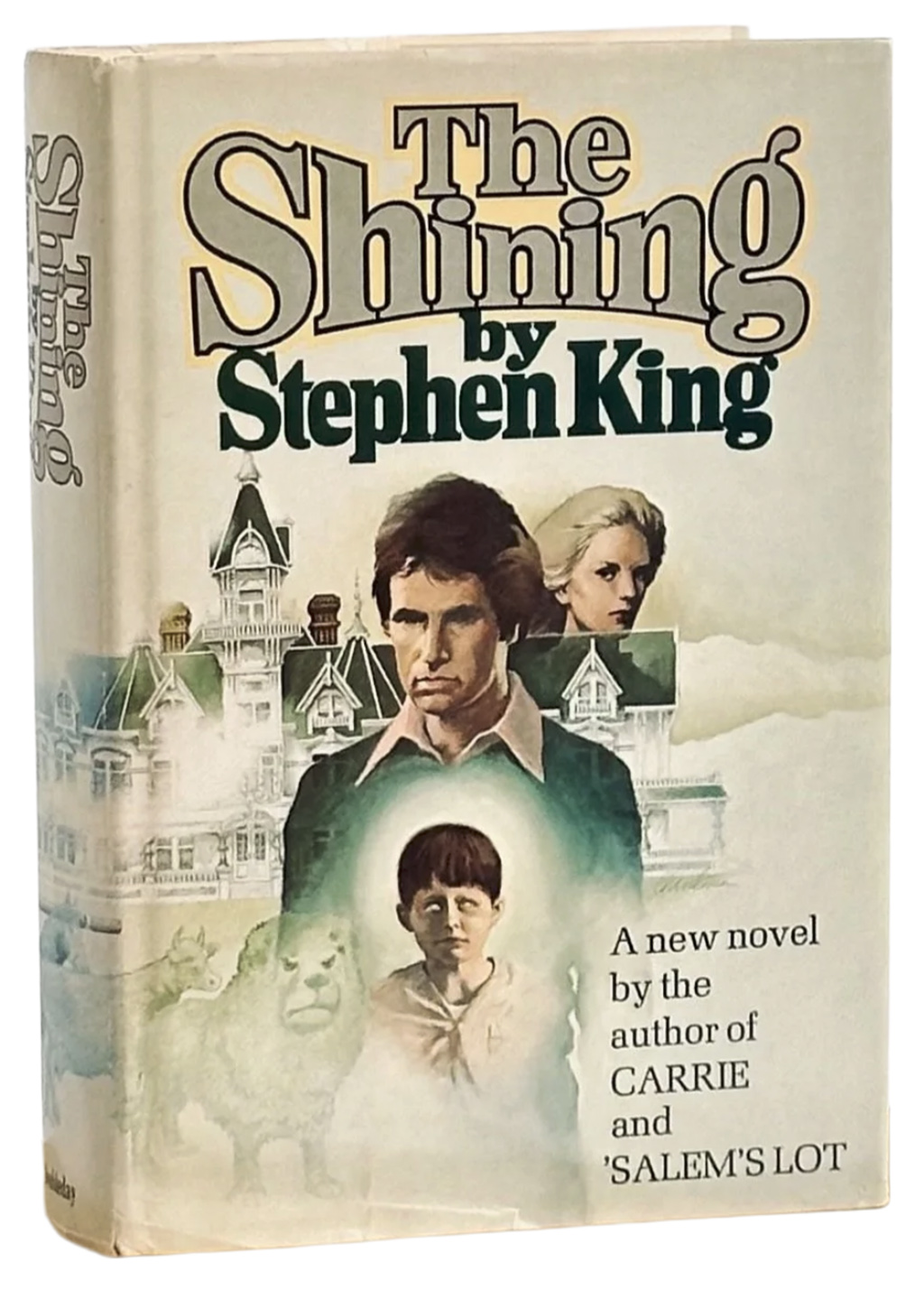

Bhob: How do you feel about the montage on The Shining hardback?

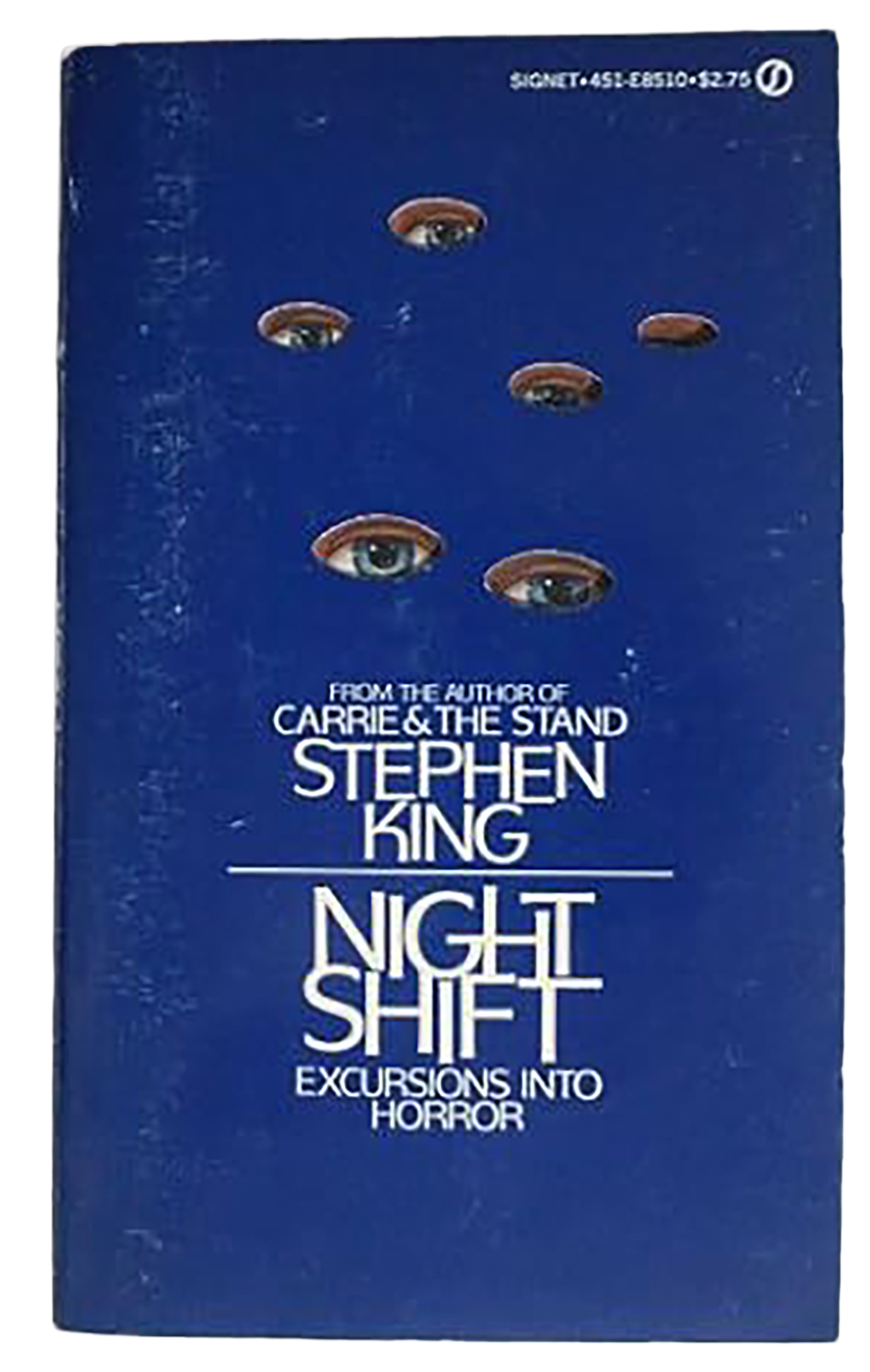

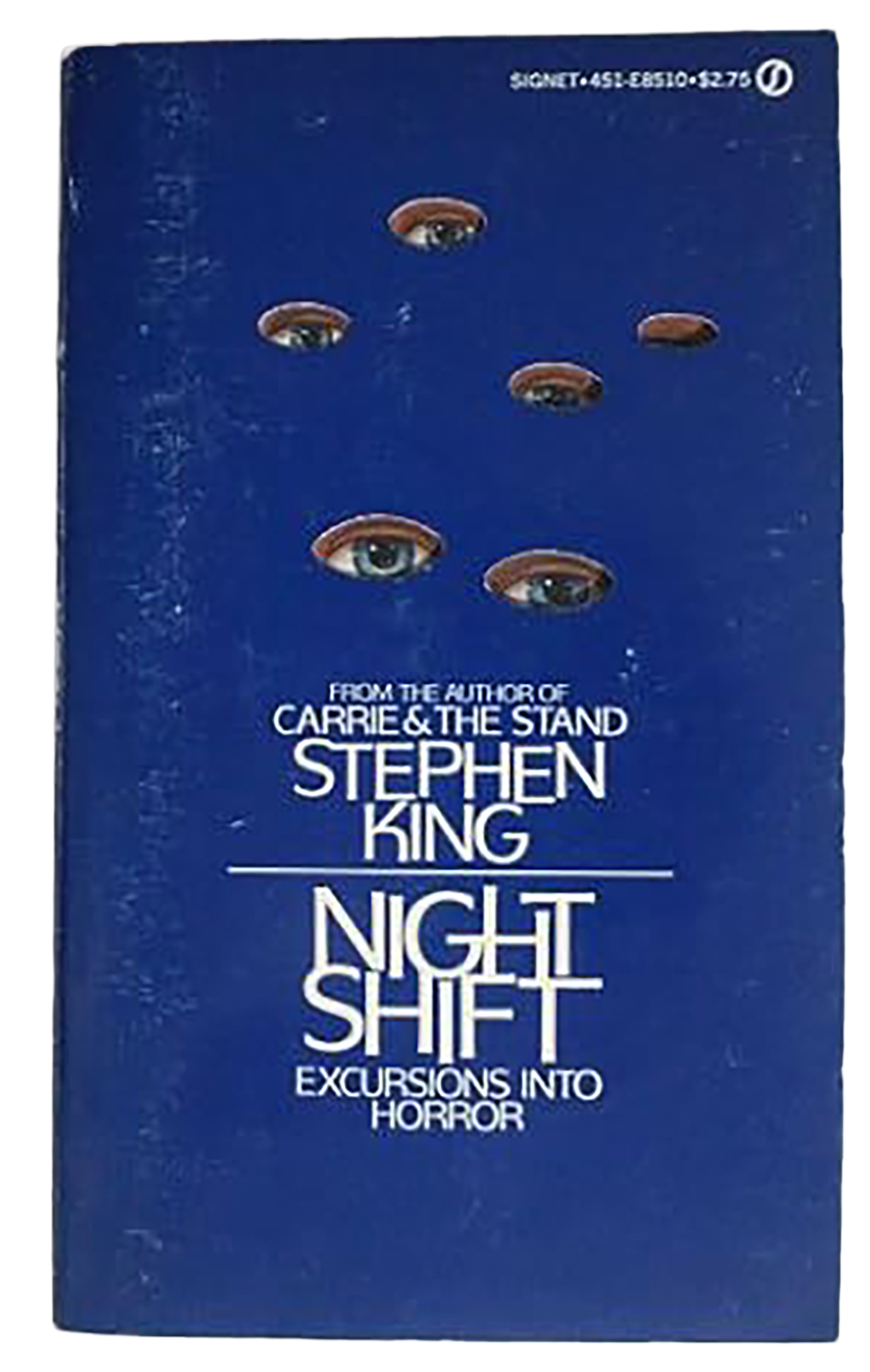

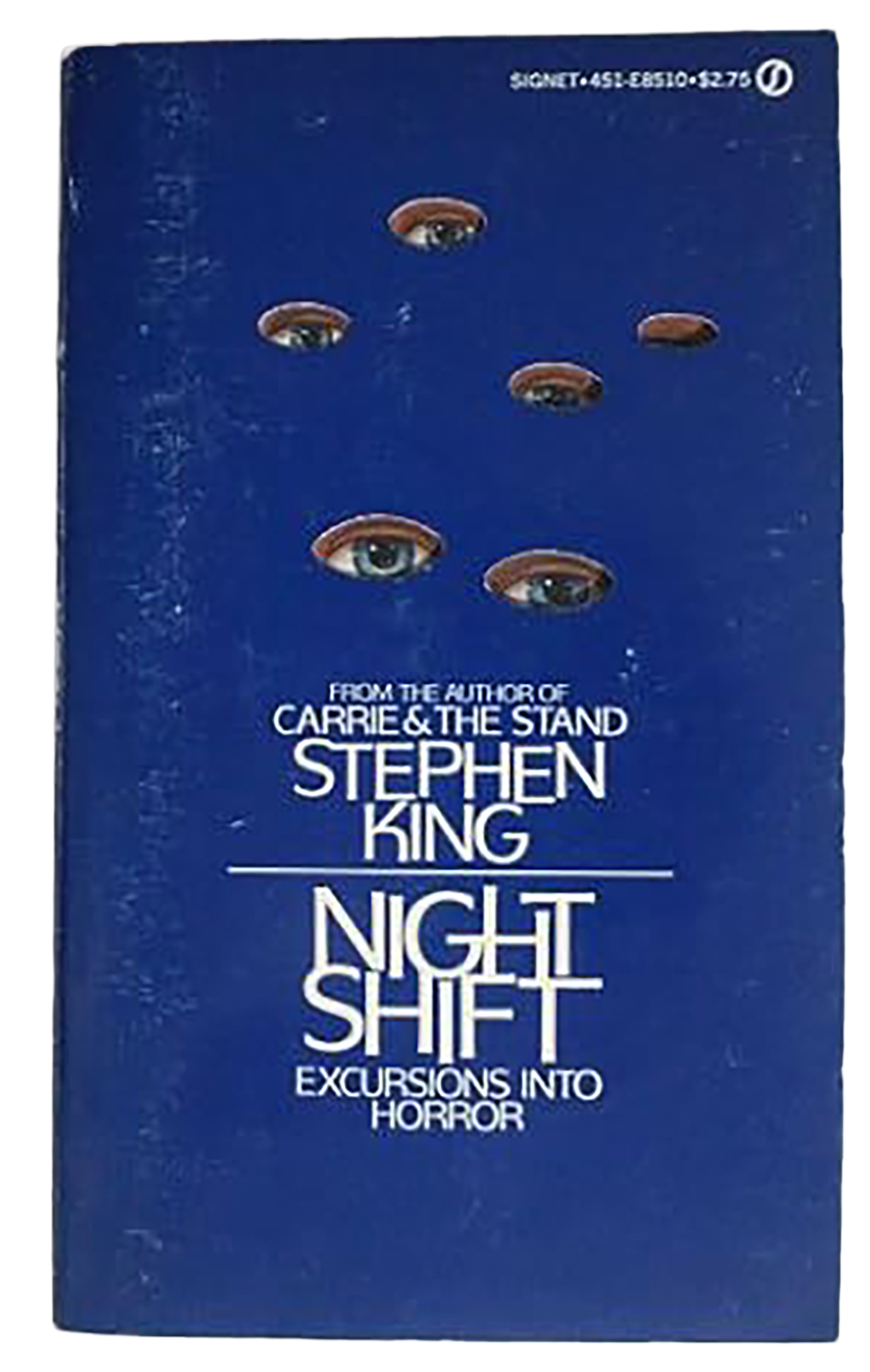

King: Don't care for that either. It makes the people look too specific. It's almost a gothic romance jacket. There are some nice things about that jacket: I object to the faces of Jack, Wendy, and the little boy, but I like the concept of having the hedge animals. The hardback Night Shift has a classy jacket of just words, but it looks like a Doubleday-type jacket for a book they didn't expect to sell. There's nothing really exciting about that graphic.

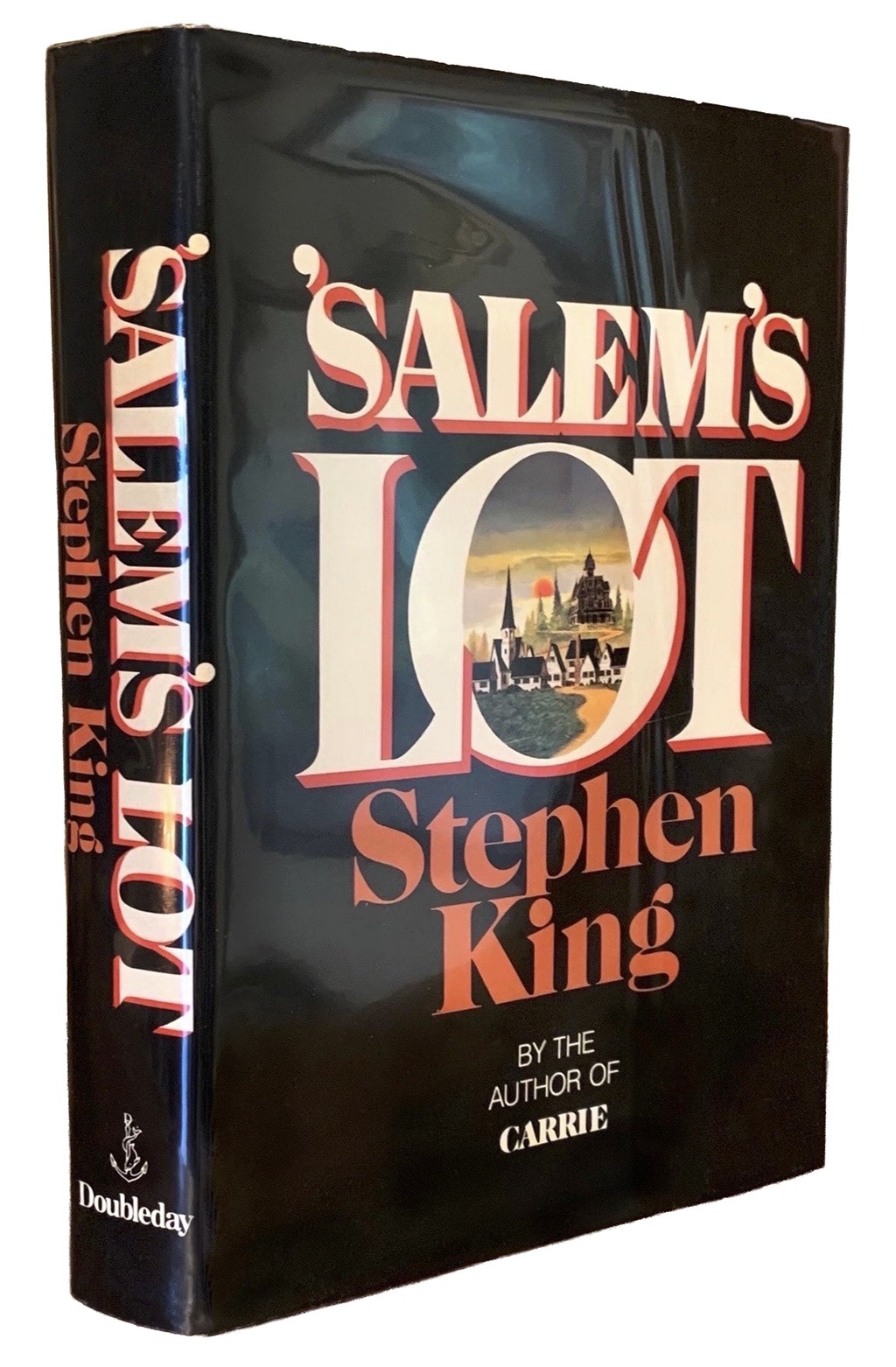

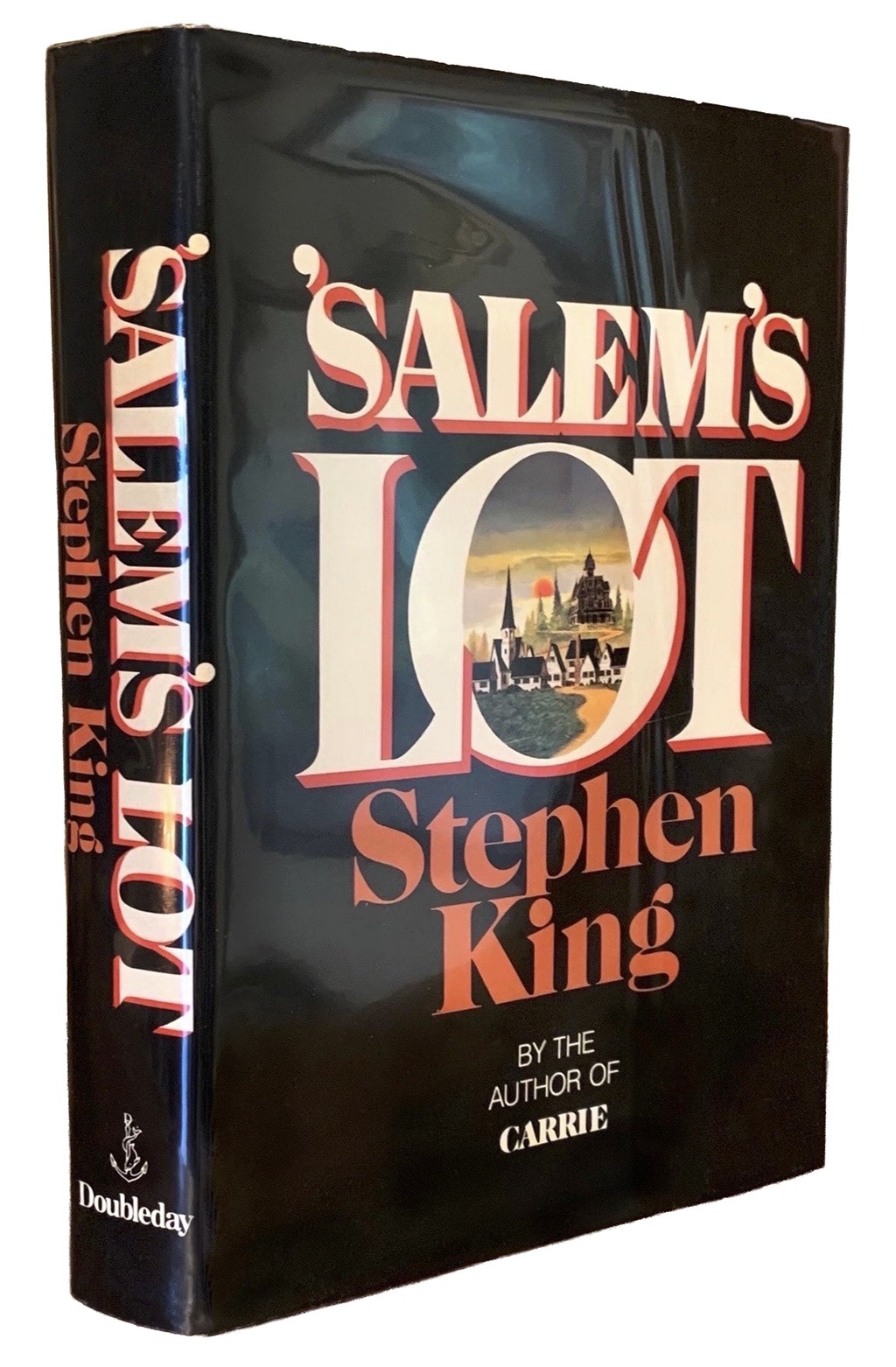

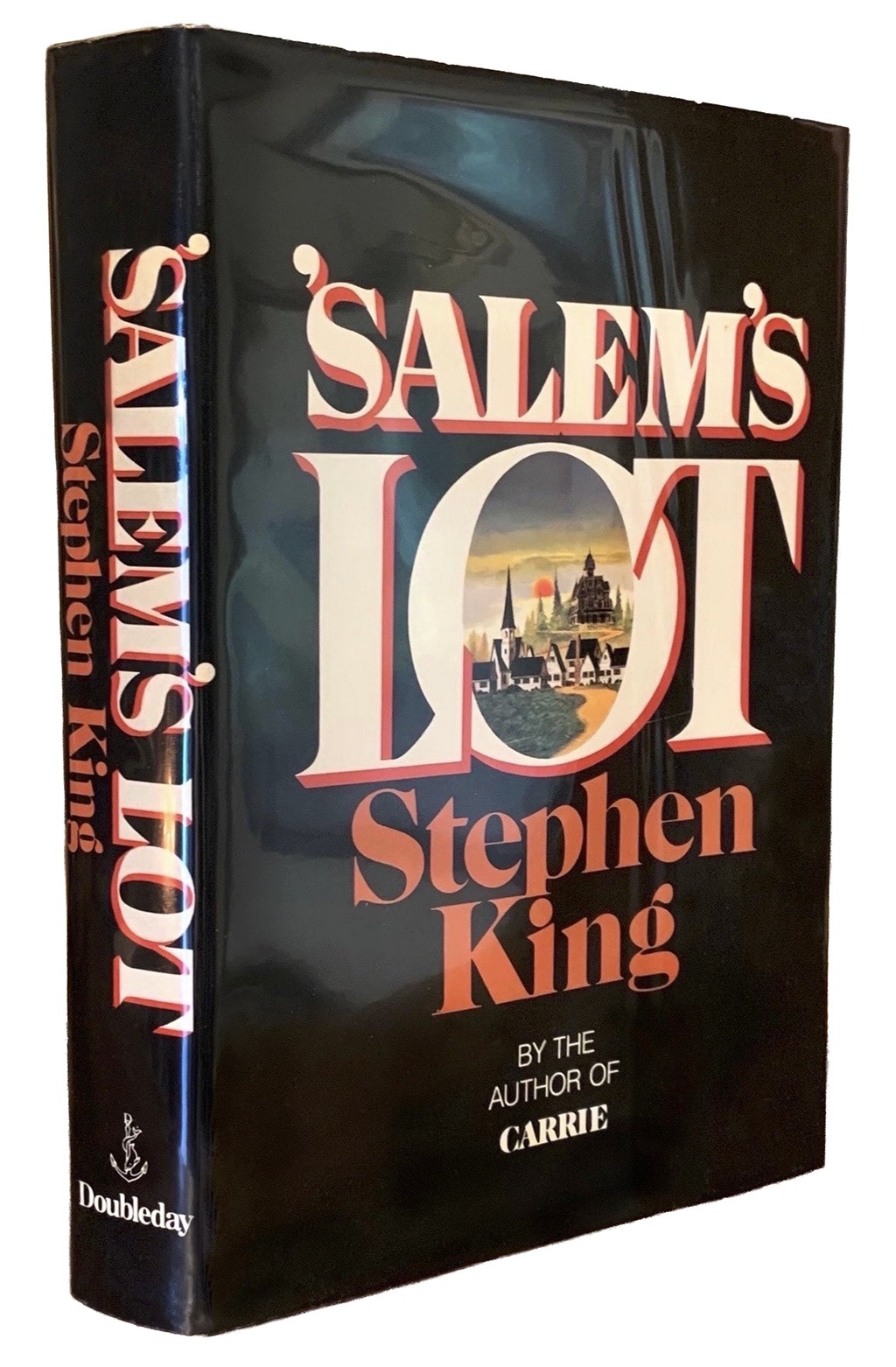

Bhob: The long-distance view of the town on the Salem's Lot hardback doesn't indicate the book's true nature.

King: I think that was intentional. The flap copy on Salem's Lot is a real collaboration: my editor wrote part of it, his secretary wrote part of it, I wrote part of it, and my wife wrote part of it. It was just an effort to say something without saying anything. Of all the Doubleday jackets, I think that I like The Stand the best, but Salem's Lot runs a close second. I like the idea of the black background with the town inset in the "O" of Lot. You can look into the town, and you see the Marsten house.

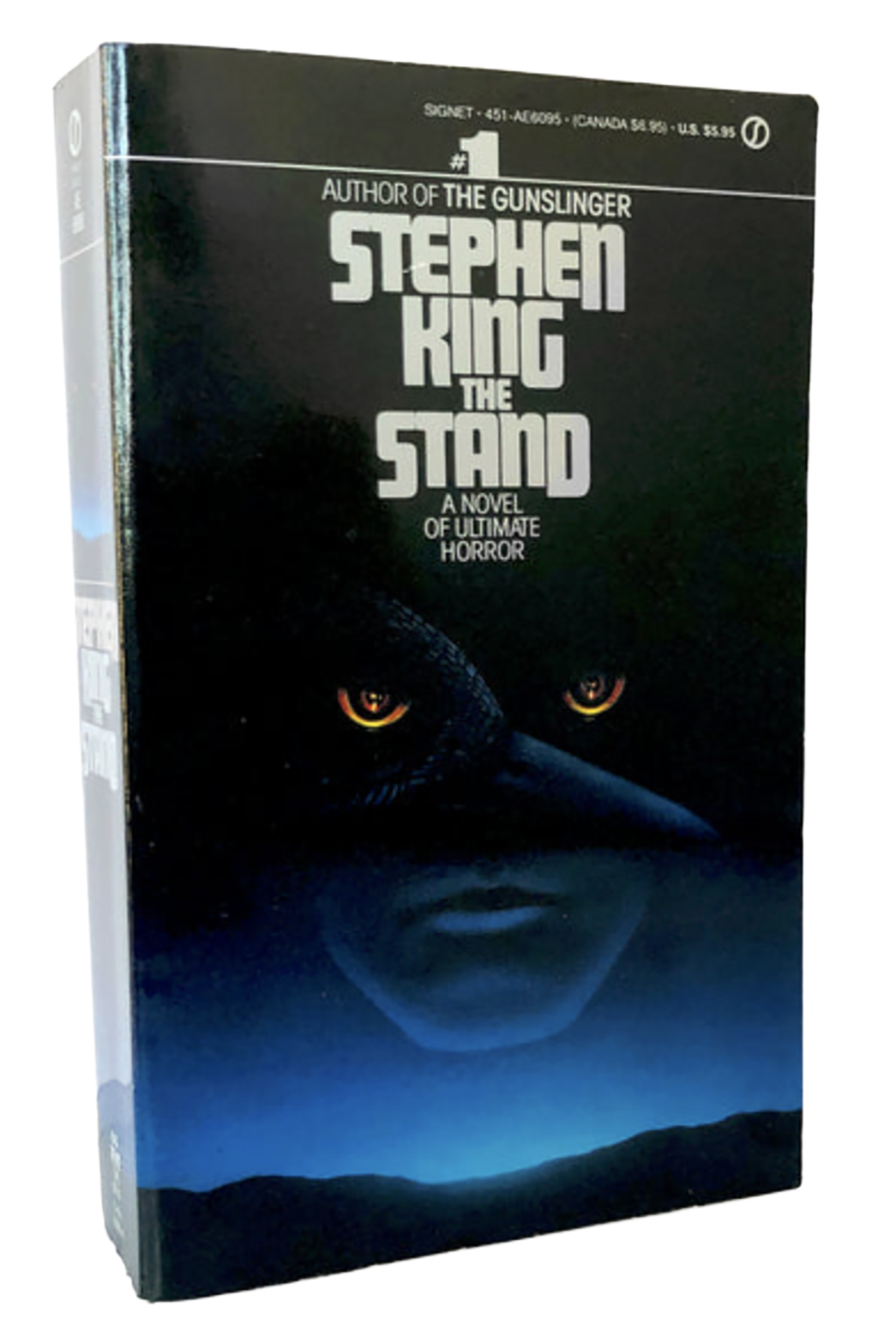

That's a pretty decent jacket. That was the best produced book by Doubleday all the way around. That was a good piece of work. The illustration for the hardback of The Stand was taken from a Goya painting, "The Battle of Good and Evil," it was repainted. I was mad that they didn't give poor old Goya a credit. There are a lot of people who are rather literal-minded, kind of nerdy about book jackets, who don't like it because they say that it doesn't look like what the book is about, it looks like what the spirit of the book is about.

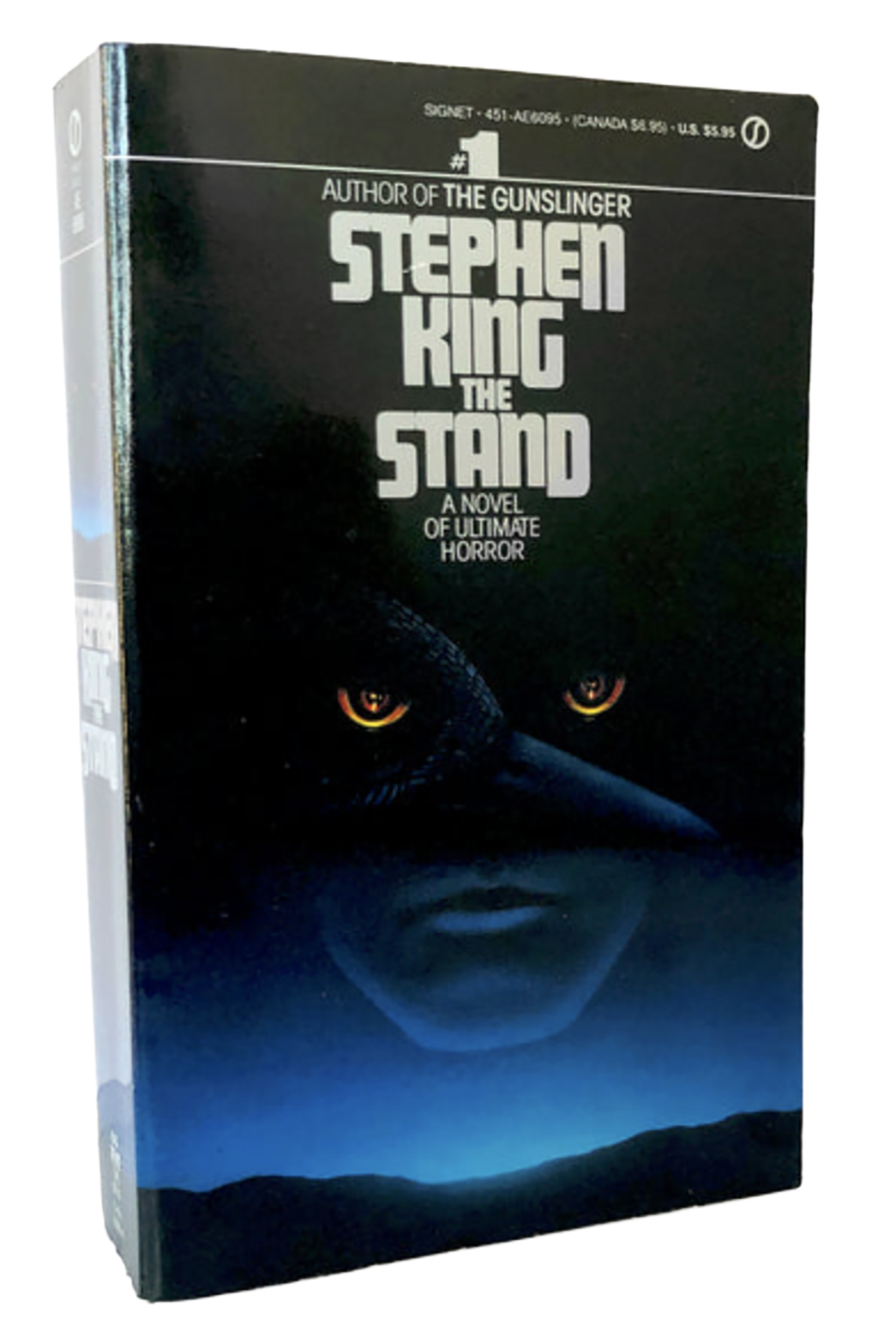

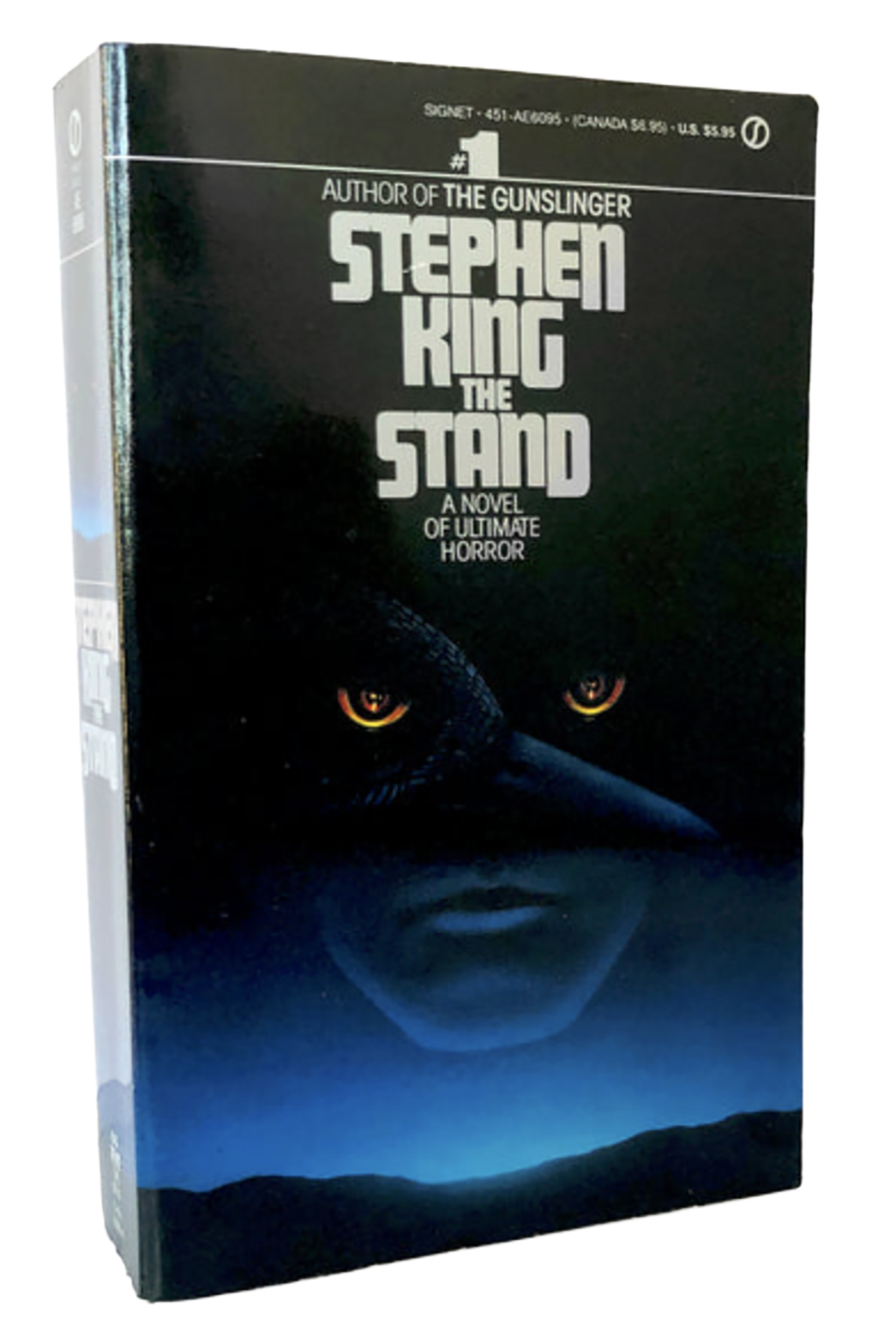

NAL's The Stand cover is super. I think that it's a good one. I like the dark blues and turquoises in it. The paperback covers have always been better because paperback people seem to understand how to market books, how to go about that. Illustrators and designers don't get credit on paperback jackets the way they do on hardcovers.

Bhob: Then there's The Shining in mylar...

King: Except that it was discontinued, as was the dead black cover on Salem's Lot. Both of those were expensive covers. The Salem's Lot cover cost seven cents right off the top of a book for $1.95. The mylar was nine cents, and in addition, the mylar cover buffs. It doesn't peel, but the lettering and picture gradually buff off the book. Now they just have a plain paper cover with the same picture; it's not as eye-catching, but it lasts longer.

Bhob: Did it occur to you that the wearing away of fragments of The Shining's cover produces strange, corrosive effect that some readers might consider an additional horrific bonus?

King: I hadn't thought of it that way — maybe it is. There are people who treasure those copies: someday maybe those will be worth some money, especially the ones that are in good condition, because on the ones that have been read, the cover wears off very quickly. The mylar was really discontinued not just because it buffed in people's hands, but because it buffed in the boxes when they were shipped. I also like the paperback Night Shift cover: it's a deep, dark, rich blue. Some of the editions are perfect, and on some, the holes are not over the eyes. Again, that was a difficult one to do, there is such a thing as being too clever by half.

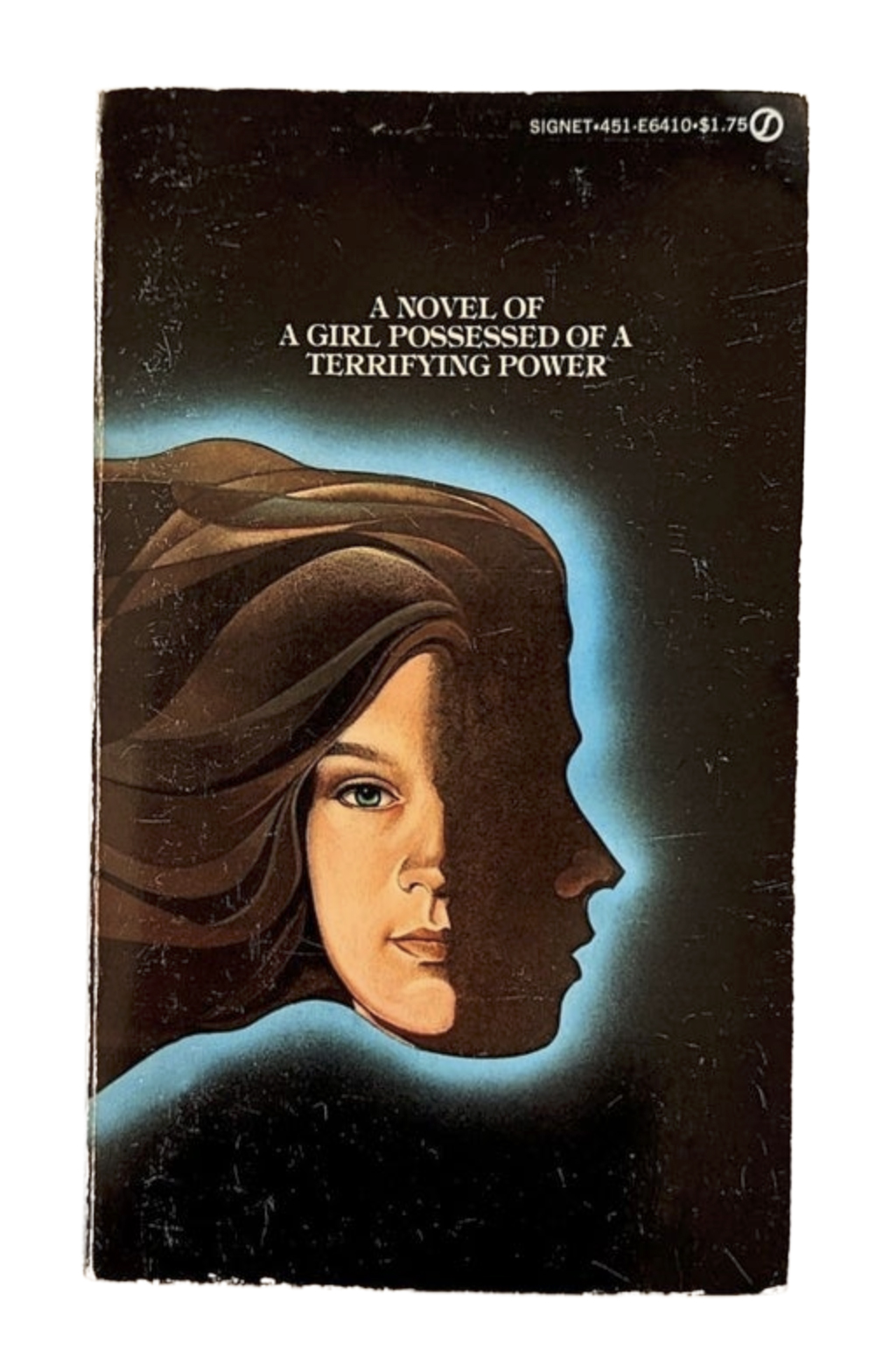

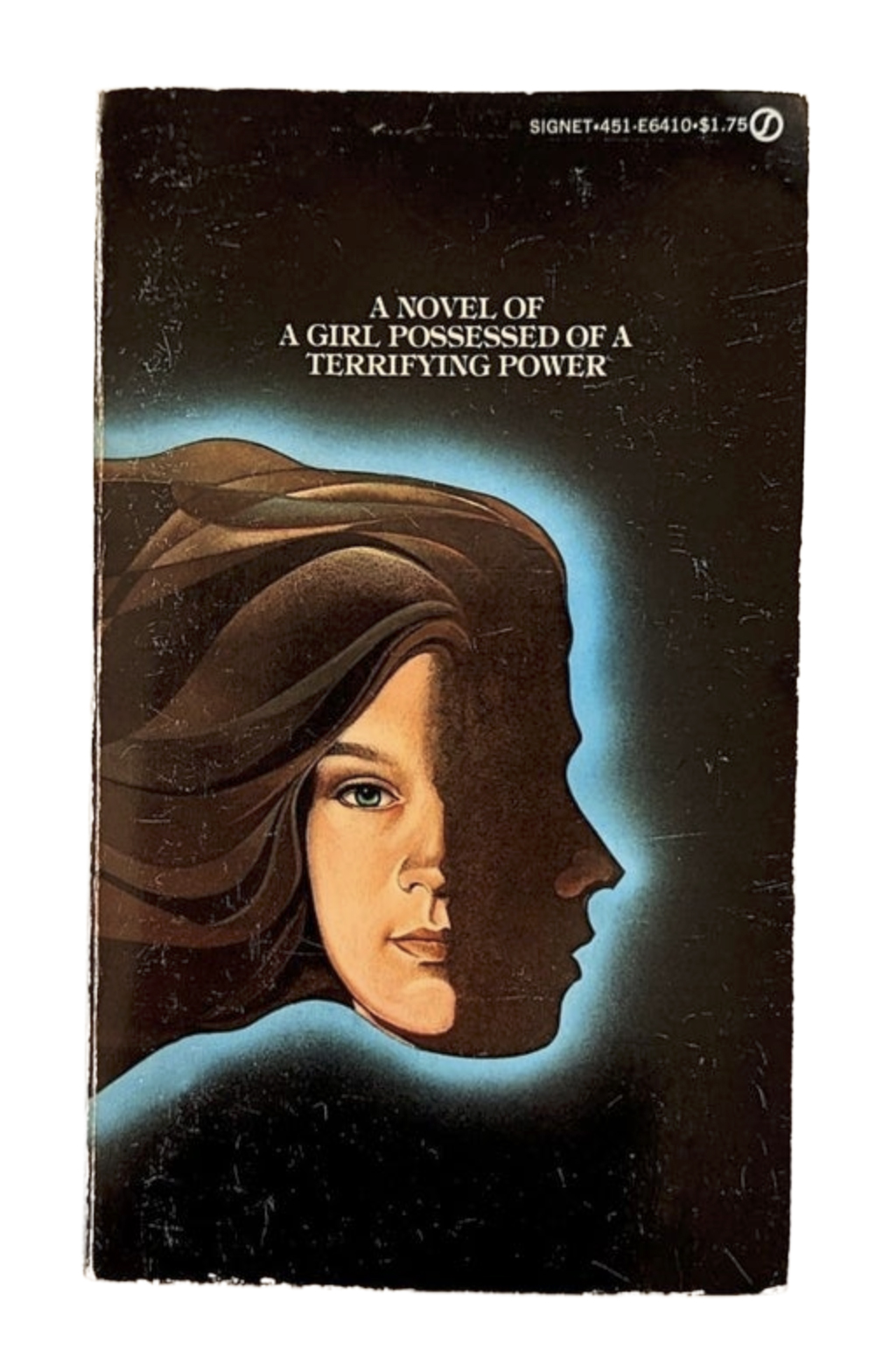

Bhob: What was on the Carrie paperback before the movie tie in?

King: That cover has gone totally out of print. The original paperback had no title, no author, no printed material of any kind on the front cover. It simply showed a girl's head floating against this blue backdrop — a pretty girl with very dark hair swept back. It was a painting, a rather nice one by James Barkley. Inside, there was a second jacket. Originally, it was to have been die-cut down the side in a two-step effect: the title, "Carrie," reading vertically down the right-hand margin, was supposed to show, and at the last minute, their printer told them that he couldn't do it. Inside there's this town going up in flames, and that is an interesting effect. You reach the end of the book, and there's a photograph on what they call the third cover of the same town crumpled up into nothing but ash. I don't know if that's ever been done before: having another picture inside the back jacket. These were photographs by Allen Vogel of flames and a model town that looks as though it was one of these origami things created out of cardboard.

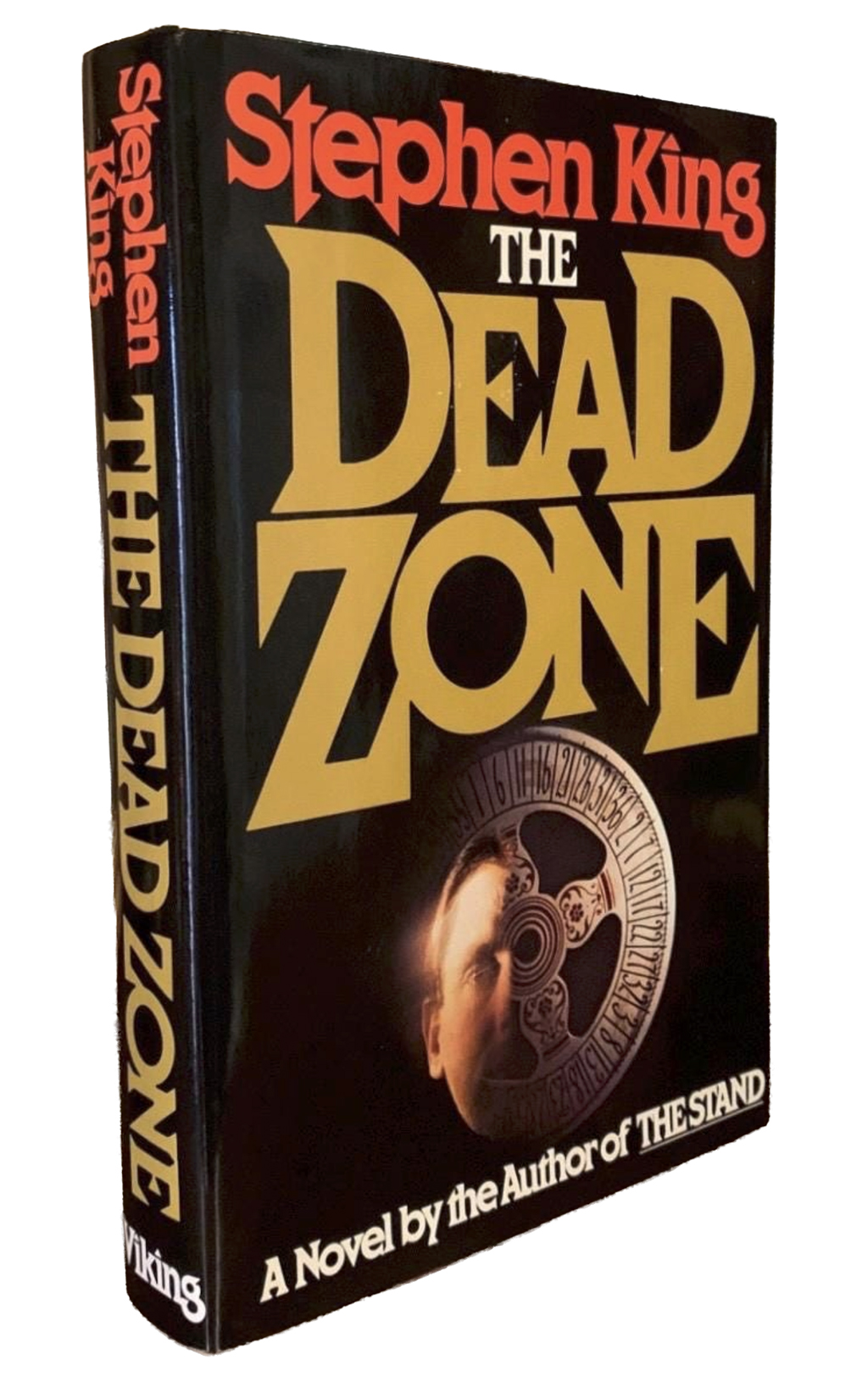

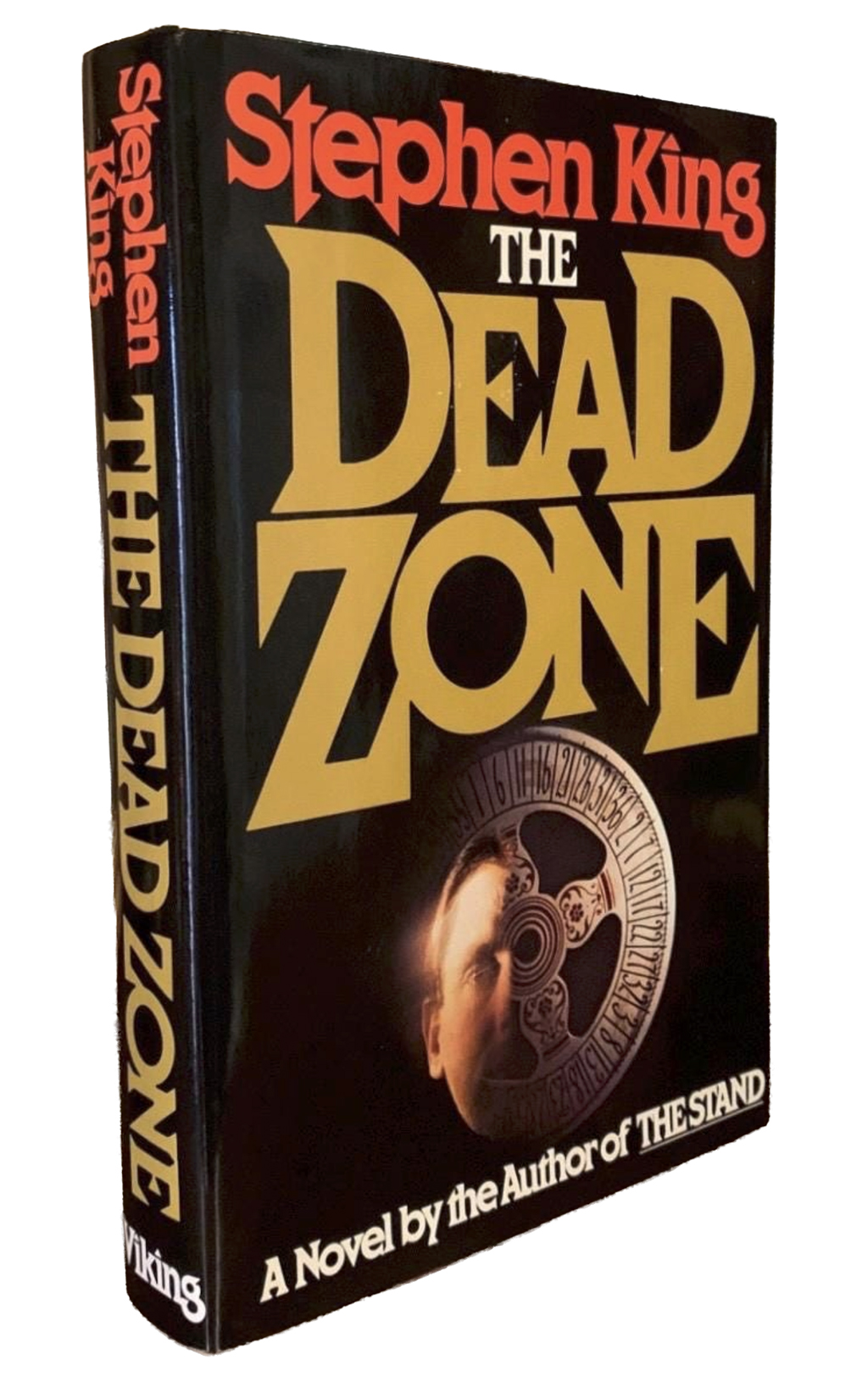

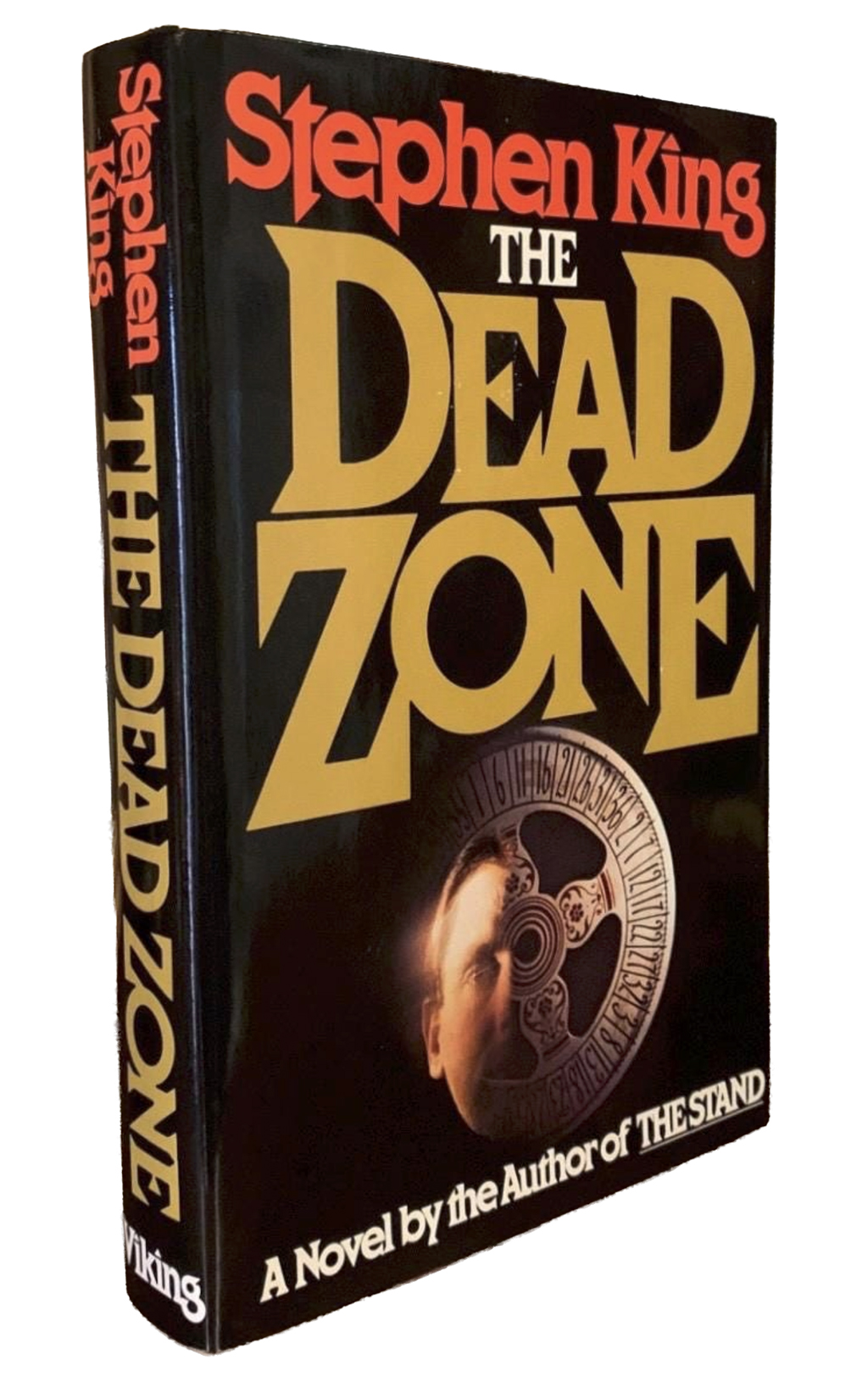

Bhob: The One + One Studio's design for The Dead Zone (Viking) illustrates the repetitive wheel-of-fortune device used throughout the novel.

King: I like that jacket pretty well. I think that, in a large measure, it's been responsible for some of the book's success because it's a very high-contrast type. Something I think Viking might have lifted from the paperback houses. It comes out at the reader because there's so much black. The thing I don't like is the photographic effect. I've never cared for photographed jackets. I can't really even say why, but they seem too realistic to me. I would have liked that jacket better if it had been that same cover design-only painted.

By the time you get up to six books, you have mixed feelings. Salem's Lot was the best-produced of the Doubleday books. Night Shift would be second, and probably The Shining, third. The Dead Zone is the best produced of all the works. But it's more than just cover. The cover is something that you hope entices readers who don't know your work to take a look. But it probably doesn't mean that much to people who have read you before. If they really turn on to what you're doing, they look for the name, and they'll buy the book on the basis of that. Like this new Led Zeppelin album packaged in brown paper with "Led Zeppelin" stamped on the front — you buy the name. I like books that are nicely made, and with the exception of Salem's Lot and Night Shift, none of the Doubleday books were especially well made. They have a ragged, machine-produced look to them, as though they were built to fall apart. The Stand is worse that way; it looks like a brick. It's this little, tiny, squatty thing that looks much bigger than it is. The Dead Zone is really nicely put together. It's got a nice cloth binding, and it's just a nice product.

Bhob: With The Dead Zone having climbed so high on the best-seller list...

King: Wonderful. I love it.

Bhob: Have there been any film offers?

King: Lorimar bought it for Sydney Pollack to direct, and it would be produced by Paul Monash, who produced the film of Carrie, and also written by Monash. And if for some reason Monash's screenplay was unacceptable, or Monash had to leave the picture, I'd get second shot. Or at least we're trying to work that detail out. That's not in the deal that we okayed, but we're going to try to get that. They bought it for well in excess of a quarter of a million dollars. They paid good money for it, so I'm hoping to see a front line theatrical film out of it - depending on how fast they move.

And that's the deal.

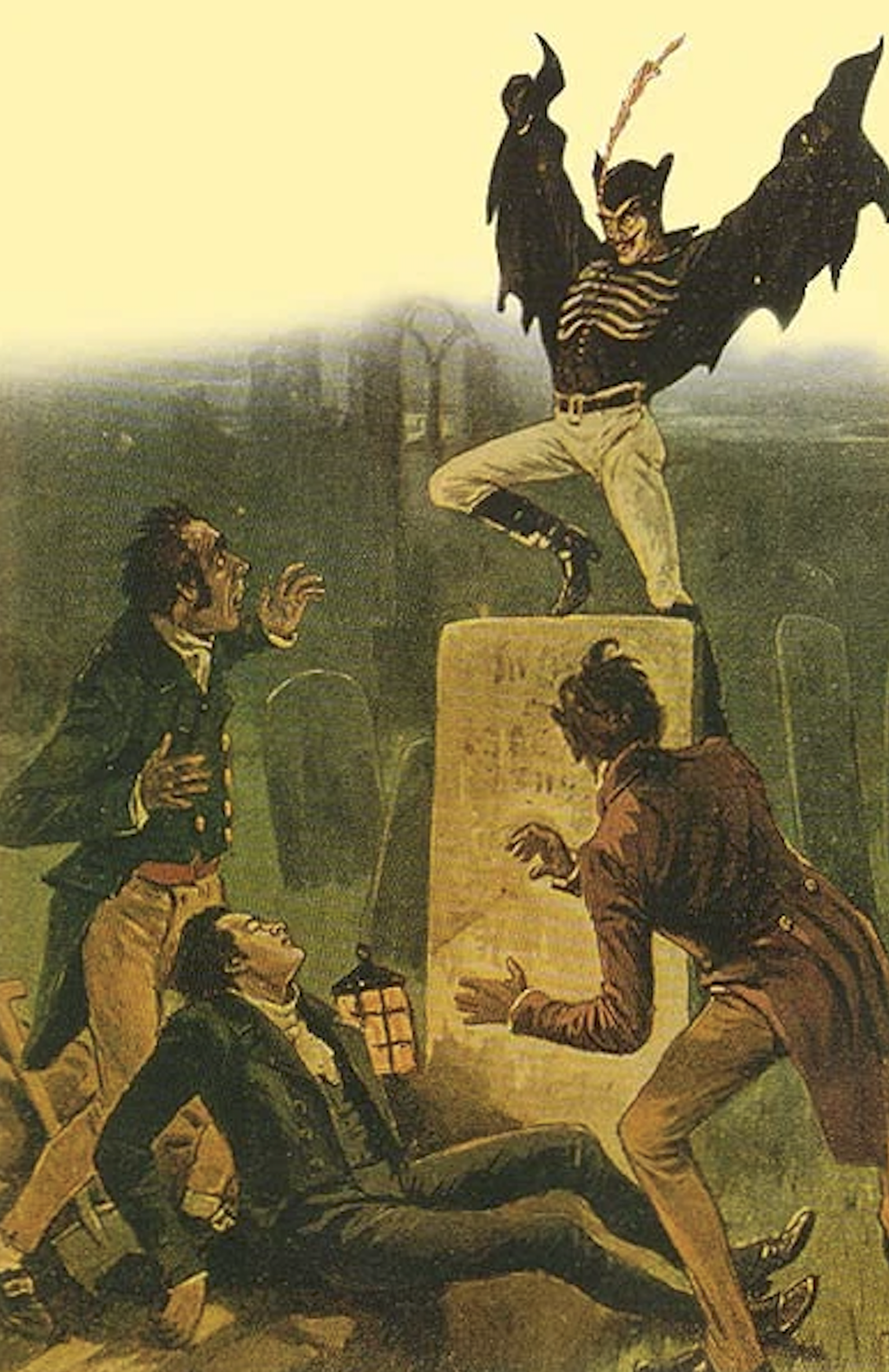

Bhob: In "'Strawberry Spring" you wrote about Springheel Jack. The few mentions of Springheel Jack that I've run across seem to indicate that he was a mythical British character who was luminous and was witnessed leaping twenty-five or thirty feet.

King: Yeah. That's him! That's him! My Springheel Jack is a cross between Jack the Ripper and a mythical strangler - like Burke and Hare or somebody like that.

Bhob: But you embellished that history?

King: Yeah, right. I did. Robert Bloch has also done some of this embellishing, and he mentions Springheel Jack in a third context. He's like Plastic Man or Superman — a weird folk hero.

Bhob: I think it was a nonfiction UFO book where I first encountered a description of him suggesting -

King: A creature from outer space. [See Jacques Bergier's Extraterrestrial Visitations from Prehistoric Times to the Present, New American Library].

Bhob: What happened to the Night Shift TV anthology pilot planned trilogy of Strawberry "I Know What You Need" and "Battle -

King: It's not going to be done for TV because NBC nixed it... too gruesome, too violent, too intense. It's the atmosphere of TV today; five years ago it would have been done, but the standards and practices people just said, "No." What's going on now is that the production company people have gone to Martin Poll in New York, and he would like to produce it. So we'll see what happens. I don't think anybody's falling over themselves to do it right now.

Bhob: But "Battleground" seems more like a story that would work in a Milton Subotsky film rather than being grouped with the stories set in -

King: The way this works out is that... I can see a lot of possibilities that just can't be realized because people take these options in a harum-scarum way, and then they're cut out. We discussed this with the trilogy for NBC. There's a rooming house in the town, and the hit man from "Battleground"' lives in this rooming house. The premise is that reality is thinner in this town, and things are weird in this one particular place. There are forces which focus on this town and cause things to happen. On the other hand. there's another college story, set on a mythical campus, Horlicks University, called "The Crate." It was published in Gallery [July, 1979) - and that's the third college story. So you have "Strawberry Spring," "The Crate," and "I Know What You Need," which are all really set on the same campus. They are called by different names because I invented Horlicks later. They'd make a beautiful trilogy together, but there's no way that we can do that because George Romero owns "The Crate" and these other people own the other two.

Bhob: Kubrick's film of The Shining reportedly replaces your topiary animals with a hedge maze, an idea you had originally considered. On page 203 of the book, there's a mention of hedge billboards in Vermont. Do these exist and is this what inspired your topiary?

King: They're really there. The idea for the hedge maze is really Kubrick's and not mine. I had considered it, but then I realized it had been done in the movie The Maze [1953] with Richard Carlson, and I rejected the maze idea for that reason. I have no knowledge as to whether or not Kubrick has ever seen that movie or if he'd even considered that or if it just happens to be coincidence.

The billboards advertise some kind of ice cream, they're on Route 2 in Vermont. As you come across this open space where there are no trees, you can look across this rolling meadow to the land which I assume that the ice cream factory owns. The words of the ad have been clipped out of hedges. To heighten the contrast, these hedges have been surrounded with white crushed stone so that the letters just leap right out at you. You know the first time you see them that there's something very peculiar about them, and then you realize, as you get closer, that it may be one of the world's few living signs - because they're hedges. But I got the idea for the topiary from Camden, Maine - where Peyton Place [1957] was filmed. You come down Route I, you go through Camden, and there are several houses there that have clipped shrubs.

They're not clipped into the shapes of animals, but they're clipped into very definite geometric shapes.

There's a hedge that's clipped to look like a diamond. That was my first real experience with the topiary. There is a topiary at Disney World where the hedges are clipped to look like animals, but I saw that long after the book was published. In some ways, I like Kubrick's idea to use a maze. Because it's been pointed out to me — and I think there's some truth to this - that the hedge animals in my novel are the only outward empiric supernatural event that goes on in the book. Everything else can be taken as the hotel actually working on people's minds. That is to say, nothing is going on outwardly. It's all going on inwardly, and it's spreading from Danny to Jack and, finally, to Wendy, who is the least imaginative of the three. But the hedge animals are real, apparently, because they cut open Danny's leg at one point in the book. Later on, when Halloran comes up the mountain, they attack him. They are really, really there. Kubrick told me, and he's told other people as well, that his only basis for taking the hedge animals out was because they would be difficult to do with the special effects — to make it look real.

My thinking is that maybe the maze is better because maybe the maze can be used in that same kind of interior way. A person could get into a maze and just be unable to get out and gradually get the idea that the maze was deliberately keeping him in, that it was changing its passages - like the mirror maze in Something Wicked This Way Comes.

Bhob: When did Kubrick acquire The Shining, and why did he pick it?

King: It was bought long before publication, it was after Barry Lyndon was out. I know that Kubrick came on the scene, it seems to me, in the late summer of 1975, so it's been in process with him for about four years now. I know that he was interested in making a real horror picture. This was a stated ambition of his as long ago as 1956. I heard a story from a Warner Brothers flack that's kind of amusing. He said that the secretary in Kubrick's office got used to this steady "THUMP! THUMP! THUMP!" from the inner office - which was Kubrick picking up books, reading about forty pages, and then throwing them against the wall. He was really looking for a property. One day, along about ten o'clock, the thumps stopped coming, and she buzzed him. He didn't answer the buzz; she got really worried, thinking he'd had a heart attack or something. She went in, and he was reading The Shining. He was about halfway through it. He looked up and said, "This is the book." Shortly after that, Warners in California wanted to know if the book had been bought, and if so, who owned it and if a purchase deal could be worked out - which it could, since Warners itself owned the book. I do think that if he wanted to make an all-out horror picture, he picked a perfectly good book to do it with, it's a scary book.

I've had some people say to me, "I wonder what it would be like if he'd done Salem's Lot," but I can't see Kubrick doing that because it's too much of a conventional horror story. Somebody in Film Comment described Salem's Lot as a "reactionary" horror story. They imputed a lot of things about what the book was saying, as being a subconscious putdown of gays and any kind of deviant life style — which is nothing but pure bullshit. The article is mainly about Larry Cohen, who did It's Alive [1974). At one point it looked like Cohen was going to write, direct, and produce Salem's Lot. The writer felt it would be funny to see such a sensibility as Cohen's - who is antiestablishment in that in It's Alive and It Lives Again [1978) he looks at this family unit that's breaking down; it's being eaten up by what you'd think of as the safest member of the family group, the baby. The babies turn out to be these flesh-eating, vampire-type creatures. The writer said it would be interesting to see what would happen when Cohen tried to adapt my material, which was "reactionary." (laughs)

Bhob: In The Shining, I noticed a curious bit of synchronicity. Danny's experience in Room 217 takes place on page 217.

King: It's been pointed out to me before.

Bhob: It's very strange.

King: (Laughs) Is that in the paperback?

Bhob: Yes.

King: I don't know if that happens in the hardcover or not. Just a minute. I never thought of that. [He turns to page 217 of the hardcover edition.] It's Room 217, and it's on page 217. It is. It's peculiar. This Judith Wax book, Starting in the Middle, this is really creepy. She was one of the people killed on that DC-10 that crashed in Chicago.

Bhob: She did the annual Playboy feature, "That Was the Year That Was."

King: She worked for Playboy, and she also wrote humorous books — a little bit more literate than, say, Erma Bombeck's books. She talks in that book about her fear of flying and how she's convinced that she's going to die on a plane - which she did. The passage where she discusses that is on page 191 of the book, and the flight number of the plane that crashed was 191.

Bhob: Did she write that as a humor piece?

King: She approached it humorously, but, at the same time, people who have read the book say you can see that she really hated to fly.

Bhob: In the film, Room 217 has reportedly been changed to Room 237 for legal reasons. What legal reasons?

King: I don't know what the story is on that. I've also heard that, but I don't understand why. I popped the numbers right out of the air. It was just a number to give the room, but there was no significance to those numbers.

Bhob: Did Kubrick shoot test footage to see what the topiary animals would look like in stop-motion animation?

King: Yes. That's right. He did. He had somebody do that - somebody in Europe. I think that no matter how well it was done, it would be difficult to believe. It's not difficult to believe somehow in your head when you're reading the book, but I think that a movie is a different proposition. So I'm not really put out that he's not using the hedge animals. I know people that are really disappointed, but they're the sort of people that rarely read a book before going to see a movie. And when they do, by God, it had better conform to what they read, or they're going to be really upset.

Bhob: It seems to me that you often take the most preposterous situation you can dream up, and then you set out to convince the reader it's plausible.

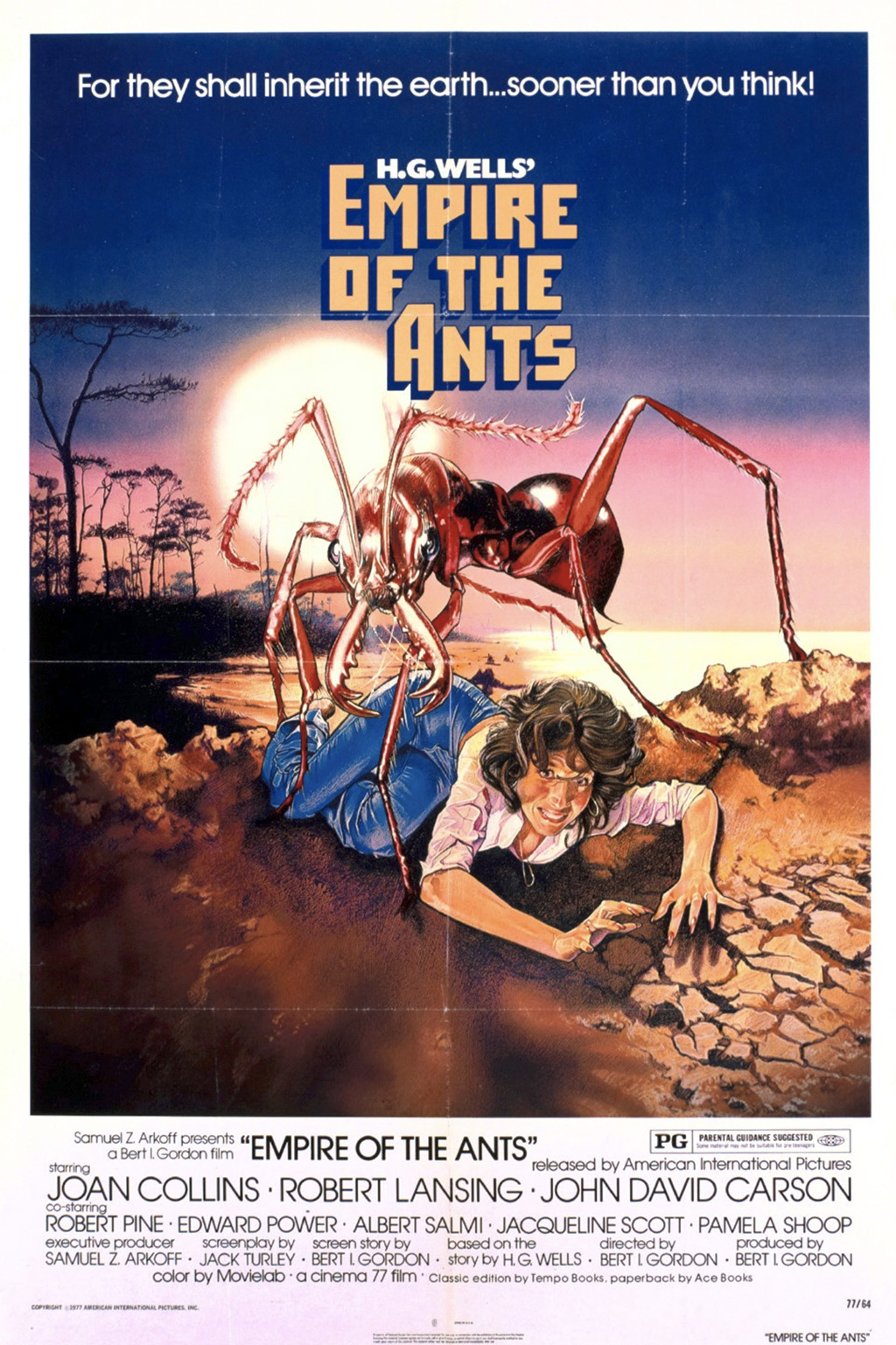

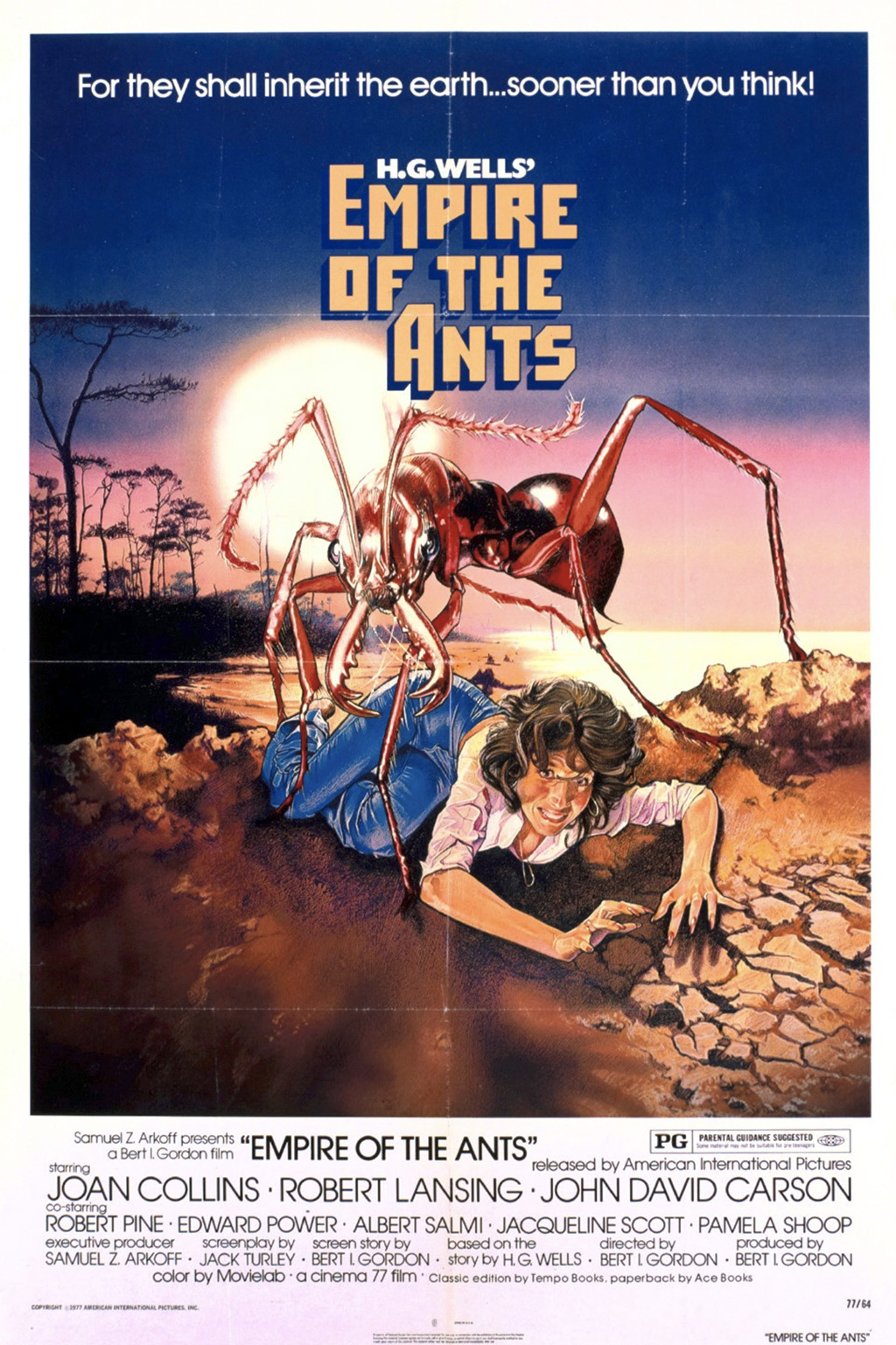

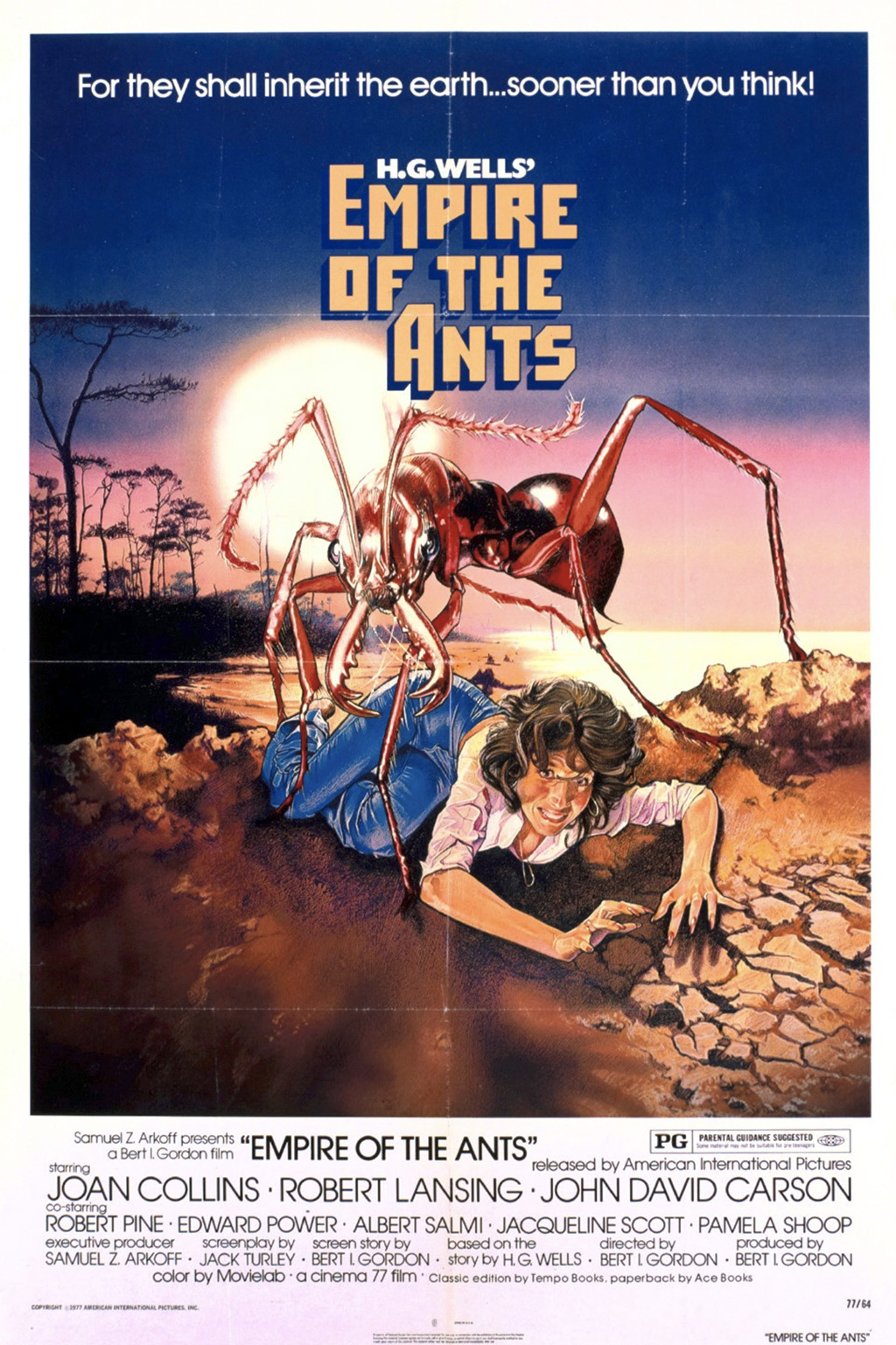

King: Yes, I do. I've got a story coming out in an anthology edited by Kirby McCauley, it's really a short novel called "The Mist." I said to myself, "You know all these grade-B movies, these drive-in pictures. I want to do something like that." The real proponent of what I was trying to get at in this story was a guy named Bert I. Gordon. He does big bugs and things like this — or he did. They're always sort of funny; there's nothing really terrifying about even the best of them. They're just sort of fun when they're good. The one I like the best, Empire of the Ants (1977), is just fun; this is about people inspecting an island where there are going to be condominiums, and the ants are out of control. I said to myself, "Let's take all those B movie conventions. Let's take the giant bugs and everything, and let's take the most mundane setting I can think of." Which, in this case, was a supermarket. And I said, "I want to set these things loose outside and see if I can do it and really scare people... see if I can make that work." And, by God, I think I did. You can judge for yourself. Kirby's book, Night Forces, will be out next year. The story is about forty-thousand words long and I think it's really good. There are about eighteen or twenty original stories of the supernatural in the book and he did a whale of a job. He got Joyce Carol Oates and Isaac Bashevis Singer.

Bhob: Sort of like a Dangerous Visions of horror?

King: That's what he had in mind, yeah.

Bhob: What's this about worms crawling out of Jack Nicholson's head in The Shining?

King: Yeah. A larger-than-life replica of Nicholson's head was constructed. I think that Dick Smith worked on the make-up along with a lot of other people, and that it cost a lot of money. There have been rumors that the head splits open and worms crawl out of it.

John Williams is going to do the music for The Shining. Kubrick has been known for his big, expensive movies that tend to be more arty than commercial, particularly Barry Lyndon, and he's indicated in what direction he's going by having some very obscure music. And he's used a lot of classical stuff. But Williams is a very commercial music maker for the movies, so I think that points at the fact that Kubrick really is trying to make a blockbuster. People are starting to call it a blockbuster already, and nobody's even seen a frame of the footage — so he's got good word-of-mouth going. A cameraman on The Shining, who also worked on Salem's Lot, said that he had never seen anything like it. He thinks it's going to be a dynamite, fantastic picture.

Bhob: Did your New York Times Book Review piece on David Madden prompt any increase of interest in his novel Bijou?

King: I don't know if it has or not. Madden has just published a sequel to it called Pleasure Dome and I knew that he was working on that. He and I correspond back and forth at irregular intervals, and I mean really irregular because he's not a very good correspondent and neither am I. He's interested in a lot of the same things I am: the hard-boiled writers of the thirties, the sort of writers who produced film noir in the forties - Cain and Dashiell Hammett and people like that. He's got a critical magazine called Tough Guys for which he writes these critical, very literary pieces, and he asked me if I would contribute a piece on Cain. I told him, yeah, I would, but I never have. Mostly because that literary, sort of stuffy style kind of bums me out.

Bhob: What was the name of the NBC radio program on which your mother played the organ?

King: Ah, God! It was a church show. It was on at ten o'clock, NBC, on Sunday mornings and it was something like "The Church Today" or something. I guess it really was a radio broadcast from church where they had the remote.

Bhob: Has anyone acquired your Children of the Corn screenplay?

King: Yes, it's been optioned now by a Maine group; they hope to go into production with it in Iowa next summer. They have a very tight budget. I did the screenplay for any mythical profits that might show up, possibly a pittance. I think I got five hundred dollars or something for it. They've done a lot of TV. They've done one feature film. It was a flop; it ran for a week in New York and then closed. They've done a lot of TV commercials. The guy who will be directing hasn't made a feature film in eight years.

They've got a wonderful production group. The name of the production company is Varied Directions and they run out of Rockport, Maine. The budget is eight hundred thousand dollars. We'll see if they can get it off the ground.

Bhob: But as "the best-selling author in the world in 1980," why are you dealing with a small, local outfit?

King: Because they're willing to make the film for cheap money, and I think that one of the attitudes in Hollywood is: "We don't want to look at anything that isn't going to cost us three million dollars." They have this tremendous urge to roll the dice for a lot of money: "Let's go twelve million dollars. Let's go sixteen million dollars." I shopped it around - Dan Curtis and some other people... and I'm the type of guy where, if a lot of people tell me something I've done isn't so good, after a while I'll begin to nod my head and say, "Well, maybe you're right. It isn't so good." But this is good. Scary. Locations in the Midwest, two major characters, very small budget. A lot of people were not interested in that, but these people were. I thought to myself, "Well, let's see what we can do. We'll do a little homegrown, a little grassroots, and we'll see if we can make this thing fly." Call it a hobby if you want.

Bhob: Has Steven Spielberg ever expressed any interest in your work?

King: No.

Bhob: Because both of you take an average man, and put him in an unusual situation in a commonplace setting, and then begin to intensify that.

King: He's good at that. He's real good at that. And it's interesting. I've got a story in Night Shift called "Trucks," which is similar to a story that Richard Matheson did in Playboy called "Duel." Both deal with trucks as monsters, but the similarity becomes a little strained after that basic premise - which is not so unusual if you've ever been caught between two of them on the turnpike. Spielberg did the TV-movie of Duel [1971], which I think is maybe the finest movie-for-television that's ever been made.

I've got one of those video cassette recorders, and I tell my wife the only reason I got that was so I could record Duel and the original Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Bhob: Since you did not want to host the proposed Night Shift TV show, and since you also turned down a directing offer from Milton Subotsky, one might assume that you have a desire to avoid the celebrity game.

King: I don't want to be a celebrity, but the telephone rang.. he was interested in an anthology program. He dangled this particular carrot in front of me, "Wouldn't you like to be Rod Serling or Alfred Hitchcock and introduce the programs?" I said, "Not for six weeks." He was kind of quiet, and he said, "What do you mean?" I said, "Do you remember the old 'Thriller' show?" He said he did, and I said, "They did an adaptation of the old Robert Howard story, 'Pigeons from Hell,' and there's one scene where a guy staggers down the stairs with a hatchet in his head. If you can give me an assurance that I can run a program with the equivalent of a hatchet in the head, we got a deal." There was this long pause, and he said, "Well, we could show him with the hatchet in his chest." And I said, "I just don't believe it!" That's where the negotiations on that stand.

As far as the movie goes, I thought Milton Subotsky was a very nice man. In fact, I call him the Hubert Humphrey of horror pictures. He's a constant Pollyanna, and he wants all his pictures to have an upbeat, moralistic theme. Okay - that's something different. I've been on tour because it's good for the book to do it, I don't really mind it, but if the situation were different, and I could do it another way, I'd sit home.

Bhob: Would such activities be damaging to your output?

King: No, I think it would just be a question of rearranging the priorities a little bit. There are people who write novels and still manage to do other things. I don't think it's ever easy. Richard Matheson goes on writing books even though he does screen-plays... and William Goldman. It could be arranged.

Bhob: Did you ever see those two TV shows Ray Bradbury hosted last year?

King: One of the Missing (on PBS)... I have that on tape. I think that was wonderful. What was the other one?

Bhob: He did an excellent job co-scripting and delivering his own copy on an ABC News Special about future space technology - so good, in fact, that I wondered why the networks haven't used him more often in this capacity. But it seems Bradbury's output as a writer dropped off when he got involved in all these deals and scripts that never took off.

King: I think you've got it exactly backward. I think Bradbury is involved with the deals and the other stuff because his output as a writer dropped off. He's not doing much fiction anymore. He's writing a little poetry, but, really, I think that we've seen all the major Bradbury books we're going to see. I think they're all out.

If PBS came to me and said, "We're going to do a ten-week series of famous horror stories. Would you introduce them?" I would do it, because the Nielsen ratings don't affect that sort of thing. If they were very, very good, they might repeat it with a second series, but if they only got two percent of the viewing audience, they wouldn't cancel the series - because they're used to that. I just don't want to go on network TV and front my face and my name in front of a bunch of junk. And I'm not going to do it.

HM Time Machine: STEPHEN KING Interview from 1980

Interview by BHOB

When Stanley Kubrick's film version of The Shining is unveiled a few months from now, it may be hailed as the greatest horror film of the century. It seems that Kubrick, not content with escalating the art of the science fiction film in 2001, long had a secret desire "to make the world's scariest movie." And he knew he had latched onto the right property when he read Stephen King's novel The Shining, about a five year old whose psychic powers trigger supernatural forces at a bizarro Colorado hotel, where he's snowbound with his mother and alcoholic father.

Stephen King grew up in the pale phosphor video-glow of the "Million Dollar Movie's" SF horrors, endlessly repeated. He was nurtured on a diet of the Big Three - Bradbury, Bloch, and Lovecraft, authors of The Guidebook to Anywhat. He devoured Fate magazine and the panels of dark pageantry in EC comics, that eruption of freaks, zombies, ghouls, and crazies whose doom wails shattered the still nights of the complacent fifties. He worked in a knitting mill and a laundromat, went to the University of Maine, and lived in "a crummy trailer" while teaching school. Today he is the world’s best-selling author of horror fiction. The kid who watched the "Million Dollar Movie" now writes million dollar novels: his current contract is $2.5 million for three books.

After carving a batch of EC-influenced short stories out of his typewriter for Cavalier and other publications, he created the telekinetic Carrie, staked out Salem’s Lot with vampires, and then decided to move his fiction out of New England: The Shining came into being when he combined a Colorado vacation with his quest for a fresh story setting. ("Nothing was coming" is the way he put it.) In Colorado it was suggested to King and his wife, Tabitha, that they stay at Estes Park’s famous Stanley Hotel (where Johnny Ringo was supposedly gunned down). They arrived at the end of the tourist season, the day before Halloween, and checked into the totally deserted resort hotel. As the only guests, they ate that evening in the abandoned dining hall, surrounded by chairs upended on tables covered with plastic sheets, while a tuxedo-clad band played a shadow waltz to the empty room. "I stayed at the bar afterward and had a few beers," King told interviewer Mel Allen. "Tabby went upstairs to read. When I went up later, I got lost. It was just a warren of corridors and doorways — with everything shut tight and dark and the wind howling outside. The carpet was ominous with jungly things woven into a black and gold background. There were these old-fashioned fire extinguishers along the walls that were thick and serpentine. I thought. 'There's got to be a story in here somewhere.'"

If you’ve read The Shining and had your mind squeegeed down the maddening halls of the book’s Overlook Hotel, then you already know that King found one helluva story there. That’s his talent: he takes a mundane, commonplace setting, adds familiar, even overworked themes, and introduces characters that outwardly seem just like people you or I might have known — but then comes King’s twisting high dive straight into the souls of these characters, a plunge of such force and intensity that he scrapes the bottom of their psychological depths before finally surfacing with whatever new book. There may be digressions and multilayers of atmospheric detail, but his storytelling is so simple and direct, there’s never a wasted word. It’s terse, thumbscrew tight, and it zips along like the calculated construction of an EC story where each drawing is a progression toward the payoff punch, the shocker in the last panel. He followed The Stand, a huge novel about a “superflu” apocalypse now, with The Dead Zone, a best-seller about a schoolteacher who emerges from a four-year coma and finds he has the ability to see a person's past and future when he touches them.

After publication, come the critics. Like this Christopher Lehmann-Haupt dude at the New York Times; he ends a rave review with this bringdown nonsense: "When I finished The Dead Zone, I found myself replaying the story in my mind the way one does after having seen a particularly compelling movie. That may not say very much for its qualities as literary art. But it's meant to tell you that the book is very strong as entertainment." C'mon, Chris! It says a great deal for literary art, and you know it! After heaping extolments right ("wonderful specificity) and left ("ominous and nerve-wracking unpredictability"). Lehmann-Haupt suddenly seems to remember that, after all, he is writing for the Times; he reverts to type (cold type, at that) and shovels his praise over with the dung of an outdated academic lit-crit argument. Of course King's prose is art! Zappa? Art! Moebius? Art! Graffiti? Art! (One wall of NYC graffiti reads, "Graffiti is an art, and if art is a crime, let God forgive us all.") Anyone raised on EC knows how art and entertainment can be the same.

The fact is that King is simply jotting down the movies he sees in his head. This explains why Lehmann-Haupt experienced afterimages, and it also explains why almost every King novel or short story either has been or will be up there on the shiver screen. This nightmare parade began with Brian De Palma's Carrie (1976), and now Salem's Lot is a 1979-80 CBS-TV mini-series directed by Tobe Hooper (director of the 1974 Texas Chainsaw Massacre). Stirling Silliphant is the executive producer for this four-hour Salem's Lot (to air on two successive nights) shot from a script by Paul Monash, the producer of Carrie and Kurt Vonnegut's Slaughterhouse Five (1972). Location filming took place in southern California last summer with a cast featuring David Soul, Bonnie Bedelia, James Mason, Lance Kerwin, Reggie Nalder, Marie Windsor, and Elisha Cook.

In addition to an original screenplay about a haunted, automated Maine radio station, King also has on hand another script, Children of the Corn, which he adapted from one of his Night Shift short stories: and he is adapting some of his uncollected stories, including "The Crate" for a George Romero film, The Creep Show. Milton Subotsky. the man who filmed EC in Tales from the Crypt (1972) and Vault of Horror (1973), has optioned six stories from Night Shift, enough to make not one, but two anthology movies: The Revolt of the Machines (Trucks," "The Mangler." "The Lawnmower Man") and Night Shift ("The Ledge," "Quitters, Inc.," "Sometimes They Come Back"). And in the fall of 1980, Everest House will publish King's Danse Macabre, an informal, nonfiction glance at the past thirty years of the horror genre in comics, movies, radio, and TV.

So maybe you only read comics and go to the movies, and you sit there sipping your cream-of-nowhere-soup and you ask me, "Okay, look, Bhob, they're gonna make movies and TV shows out of all his stuff anyway - so why should I read all these books? Gosh! They look pretty thick!" and I can say to you only: There is no movie like reading King, which is more like standing in a dream you know is a dream and crying while you watch the ripped-out, razor-slashed pages of your precious EC collection caught by the wind to flutter down the Main Street of Thomton Wilder's Our Town, Grover's Corners, New Hampshire, where these fading fifties fear sketches go skittering down the gutter past a white picket fence, coming to rest against the claws and mud-crusted fur of a thing you knew existed when you were four years old, and even if such an amalgamative Wilder/EC/Lovecraft impossiblility could happen, there is not, and never will be, such a movie, okay? The macabre, King's fiction tells us, lurks in the ordinary, waiting and beckoning. It's there. Even in a blade of grass.

Beckoning.

Ever see a Jacobsen lawnmower? Waiting on a park bench to talk with Stephen King. I stared at one, an armada of vicious whirling blades that could make you into people-sauce if it decided to come at you. I thought I heard the grass scream, realized I was entering the domain of the King, and crossed the street for the following interview.

Bhob: What is the origin of the phrase "the shining" as a description of psychic power?

King: The origin of that was a song by John Lennon and the Plastic Ono Band called "Instant Karma." The refrain went "We all shine on." I really liked that, and used it. The name of the book originally was The Shine, and somebody said, "You can't use that because it's a pejorative word for black." Since nobody likes to have a joke played on themselves, I said, "Okay, let's change it. What'll we change it to?" They said, "How about The Shining?" I said. "It sounds kind of awkward." But they said, "It gets the point across, and we won't have to make any major changes in the book." So we did, and it became The Shining instead of The Shine.

Bhob: Who is the writer who worked on The Shining screenplay with Kubrick?

King: Diane Johnson. She did a novel called The Shadow Knows. She's just published another one this year. She's a good writer. She writes reviews for the New York Times Book Review sometimes; she had one not too long ago on a book of letters by or about William Butler Yeats. Quite a smart lady.

Bhob: What is the title of the haunted radio station screenplay?

King: It doesn't have a title. I think the perfect title would be something that had four letters, but I can't think of a good word - like "W-something" - that would be creepy. Jesus, it's a wonderful idea!

Bhob: Oh, you mean a title made out of the call letters of the radio station - like Robert Stone's WUSA?

King: Yeah. Like that! Like that! Only I'd like to be able to do something-

Bhob: Ah, like "WEIR."

King: Yeah. "WEIR." That would be real good. Yeah. It's based on this automated radio station. They go completely automatic. They have these big, long drums of tape that do everything. They punch in the time. They make donuts for the announcer who comes in to give the weather. But mostly, it's just this, "Aren't you glad you tuned in WEIR?... Hi! This is WEIR, you fucking son of a bitch. You're going to die tonight." Irony like that in a syrupy voice.

Bhob: And is someone interested in this right now?

King: I've got to finish it. I'm not trying to do anything with it except finish it. I take it out every once in a while and tinker it up, but I don't really seem to have the kicker yet. There's no real urge to push it through, there's no excitement there just yet. I've got the idea, I just can't seem to hook it up.

Bhob: In Night Shift the EC influence is most apparent, yet you were very young when EC was on the newsstands during the early fifties, right?

King: I used to get some comics. I don't think they were ECs, but I used to buy them with the covers torn off. There was always somebody being chopped up and spitted on barbecue grills or buried alive. My guess is the comics predated 1955. I would have bought them, say, in the period 1958 to 1960. But they might have been sitting in some guy's warehouse.

Bhob: When did you first become conscious of EC?

King: I think we must have swapped the magazines around when I was younger. I can't really say when I became conscious of it. People would talk about them, and if you saw some of these things, you'd pick them up - even if it cost a buck. At that time you might have been able to get three for a buck, now they cost a lot more than that. When EC started to produce supernatural tales, they did it after the worst holocaust that people had ever known - World War II and the death of six million Jews and the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. All at once, Lovecraft, baroque horrors, and the M.R. James's ghost that you'd hear about secondhand from some guy in his club began to seem a little bit too tame. People began to talk about more physical horrors - the undead, the thing that comes out of the grave. I still remember one of these stories where this guy is killed by his cheating wife and her boyfriend, and he comes out of the grave. He's all rotted, and he's staggering through the street, saying. "I'm coming, Selena, but I have to go slowly because pieces of me keep falling off."

Bhob: What's the idea behind The Creep Show?

King: The Creep Show is supposed to be a comic book motif like those Subotsky films Tales from the Crypt and Vault of Horror. Neither George Romero nor I felt the Subotsky films worked very well. We'd like to do five or six or seven pieces, short ones, that would just build up to the punch, wham the viewer, and then you'd go on to the next one. Somewhere there would be a body that would come out of the ground and chase people around.

Bhob: When you were a kid, did you read Castle of Frankenstein?

King: Yes, yes. I had about seven or eight issues in sequence, and I don't know what's become of them. For every fan, that's an old sad song, but I had them all. It was, by far, the best of any of the monster magazines. I think, probably like most of us, I came to Famous Monsters of Filmland first. I just sort of discovered that poking off of a drugstore rack one day, and I was a freak for it, every issue. I couldn't wait for it to come out. And then when Castle of Frankenstein came out, I saw an entirely different level to this: really responsible film criticism. The thing that really impressed me about it was how small the print was. You know, they were really cramming: there was a lot of written material in there. The pictures were really secondary.

Bhob: I was the editor.

King: Were you really? No shit? Really? Doubly nice to meet you! Castle of Frankenstein was so thick, so meaty, that you could really read it for a week... you could. I used to read it from cover to cover, and I can't imagine I was alone in that. There was a wonderful book column in it that would talk about Russell Kirk (Old House of Fear, Surly Sullen Bell) and other people, and just go on and on. There was that wonderful project where all the movies were going to be catalogued, all the horror movies of all time.

Bhob: We never got past the letter "R" in that alphabetical listing. You credit films as a source for your writing, but how can this apply to syntax and style? And what's an example of how you might have translated film grammar into fiction?

King: The best example of that was The Shining probably. The framework of The Shining was supposed to be a Shakespearean tragedy. If you look at the book, it has five sections, originally these were labeled Act I, Act II, and on through to Act V, and each act was divided into scenes. The editor came to me when the book was done and said, "This seems a little bit pretentious. Would you consider dividing it into parts and chapters?" I said, "Yeah, if you want me to. I will,” and I did. But it was a useful device to me because it limited scenes. In each case, each chapter, a limited scene in one place - and each scene was in a different place, until near the very end, where it really becomes a movie, and you go outside for the part where Hallorann is coming across the country on his snowmobile. Then you can almost see the camera traveling along beside him. You learn syntax and you learn grammar through your reading, and you don't really study it. It just kind of sets in your mind after a while because you've read enough. Even now, if you gave me a sentence with a subordinate clause, I'm not sure I could diagram it on paper, but I could tell you whether or not it was correct because that's the mindset that I have. But to visualize so strong: as a kid in Connecticut I watched the “Million Dollar Movie" over and over again. You begin to see things as you write-in a frame like a movie screen.

I don't really care what the characters look like - Johnny Smith in The Dead Zone, or Jack Torrance. I didn't think that Jack Nicholson was right for that part, but not for any way that he looks - just because he seemed a little bit old to a degree. Although I can't always see what the characters look like. I always know my right from my left in any scene, and I know how far it is to the door and to the windows and how far apart the windows are and the depth of field. The way that you would see it in a film, in The Blue Dahlia or something like that.

Bhob: If you visualize this with sharp focus and depth of field, then why do you say you don't know what they look like?

King: What they look like isn't terribly important to me. It doesn't have to be John Wayne in True Grit. It doesn't have to be Boris Karloff as Frankenstein's monster. It doesn't matter to me. Some actors are better than others: I thought Lugosi was terrible as Dracula; he was all right until he opened his mouth, and then I just dissolved into gales of laughter.

Bhob: As you write, do you ever slip into the styles of different directors?

King: No, no. Very rarely do I ever think of anything like that. One of the strange things that happened to me was I got beaten in the Sunday New York Times on The Shining. I got a really terrible review of The Shining, accusing me of cribbing from foreign suspense films. I think one of them was Knife in the Water, and one of them was Diabolique.

Bhob: Because of the body in the bathtub?

King: Yes. What was so funny about the criticism was that by God, I live in Maine! The only foreign films we get are like Swedish sex films. I've never seen Diabolique. I've never seen any of those pictures. If I came up with them, it was just that there are so many things you can do in the field. Its movements are as stylized as the movements of a dance. You've got your gothic story somewhere in the gothic castle with a clank of chains in the night. In The Shining, instead of a gothic castle. you have a gothic hotel, and instead of chains rattling in the basement, the elevator goes up and down - which is another kind of rattling chain.

When Sissy Spacek was announced as the lead of Carrie, a lot of people said to me, "Don't you think that's dreadful miscasting?" Because in the book, Carrie is presented as this chunky, solid, beefy girl with a pudding-plain face who is transformed at the prom into being pretty. I didn't give a shit what she looked like as long as she could look sort of ugly before and then look nice at the prom. She could have had brown hair or red hair or anything, and it didn't really matter who - because I didn't have a very clear picture. But I had a clear picture of her heart. I think. And that's important to me. I want to know what my characters feel and what makes them move.

Bhob: The jacket on the hardback Carrie has nothing to do with the book.

King: Yes. Well, it doesn't. My editor and I had a concept on that, but of course, one of the things about Bill Thompson, my editor, was that he was a man with relatively little power at Doubleday, and it kept showing up in funny little ways. When I left Doubleday, they canned him. It was kind of like a tantrum: "We'll kill the messenger that brought the bad news."

Our concept of the jacket would have been a Grandma Moses-type primitive painting of a New England village that would have gone around in a wrap to the back. But the jacket was done by Alex Gotfryd, who does have a lot of power at Doubleday. What he gave us was a photograph of a New York model who looks like a New York model. She doesn't even look like a teenager.

Bhob: How do you feel about the montage on The Shining hardback?

King: Don't care for that either. It makes the people look too specific. It's almost a gothic romance jacket. There are some nice things about that jacket: I object to the faces of Jack, Wendy, and the little boy, but I like the concept of having the hedge animals. The hardback Night Shift has a classy jacket of just words, but it looks like a Doubleday-type jacket for a book they didn't expect to sell. There's nothing really exciting about that graphic.

Bhob: The long-distance view of the town on the Salem's Lot hardback doesn't indicate the book's true nature.

King: I think that was intentional. The flap copy on Salem's Lot is a real collaboration: my editor wrote part of it, his secretary wrote part of it, I wrote part of it, and my wife wrote part of it. It was just an effort to say something without saying anything. Of all the Doubleday jackets, I think that I like The Stand the best, but Salem's Lot runs a close second. I like the idea of the black background with the town inset in the "O" of Lot. You can look into the town, and you see the Marsten house.

That's a pretty decent jacket. That was the best produced book by Doubleday all the way around. That was a good piece of work. The illustration for the hardback of The Stand was taken from a Goya painting, "The Battle of Good and Evil," it was repainted. I was mad that they didn't give poor old Goya a credit. There are a lot of people who are rather literal-minded, kind of nerdy about book jackets, who don't like it because they say that it doesn't look like what the book is about, it looks like what the spirit of the book is about.

NAL's The Stand cover is super. I think that it's a good one. I like the dark blues and turquoises in it. The paperback covers have always been better because paperback people seem to understand how to market books, how to go about that. Illustrators and designers don't get credit on paperback jackets the way they do on hardcovers.

Bhob: Then there's The Shining in mylar...

King: Except that it was discontinued, as was the dead black cover on Salem's Lot. Both of those were expensive covers. The Salem's Lot cover cost seven cents right off the top of a book for $1.95. The mylar was nine cents, and in addition, the mylar cover buffs. It doesn't peel, but the lettering and picture gradually buff off the book. Now they just have a plain paper cover with the same picture; it's not as eye-catching, but it lasts longer.

Bhob: Did it occur to you that the wearing away of fragments of The Shining's cover produces strange, corrosive effect that some readers might consider an additional horrific bonus?

King: I hadn't thought of it that way — maybe it is. There are people who treasure those copies: someday maybe those will be worth some money, especially the ones that are in good condition, because on the ones that have been read, the cover wears off very quickly. The mylar was really discontinued not just because it buffed in people's hands, but because it buffed in the boxes when they were shipped. I also like the paperback Night Shift cover: it's a deep, dark, rich blue. Some of the editions are perfect, and on some, the holes are not over the eyes. Again, that was a difficult one to do, there is such a thing as being too clever by half.

Bhob: What was on the Carrie paperback before the movie tie in?

King: That cover has gone totally out of print. The original paperback had no title, no author, no printed material of any kind on the front cover. It simply showed a girl's head floating against this blue backdrop — a pretty girl with very dark hair swept back. It was a painting, a rather nice one by James Barkley. Inside, there was a second jacket. Originally, it was to have been die-cut down the side in a two-step effect: the title, "Carrie," reading vertically down the right-hand margin, was supposed to show, and at the last minute, their printer told them that he couldn't do it. Inside there's this town going up in flames, and that is an interesting effect. You reach the end of the book, and there's a photograph on what they call the third cover of the same town crumpled up into nothing but ash. I don't know if that's ever been done before: having another picture inside the back jacket. These were photographs by Allen Vogel of flames and a model town that looks as though it was one of these origami things created out of cardboard.

Bhob: The One + One Studio's design for The Dead Zone (Viking) illustrates the repetitive wheel-of-fortune device used throughout the novel.

King: I like that jacket pretty well. I think that, in a large measure, it's been responsible for some of the book's success because it's a very high-contrast type. Something I think Viking might have lifted from the paperback houses. It comes out at the reader because there's so much black. The thing I don't like is the photographic effect. I've never cared for photographed jackets. I can't really even say why, but they seem too realistic to me. I would have liked that jacket better if it had been that same cover design-only painted.

By the time you get up to six books, you have mixed feelings. Salem's Lot was the best-produced of the Doubleday books. Night Shift would be second, and probably The Shining, third. The Dead Zone is the best produced of all the works. But it's more than just cover. The cover is something that you hope entices readers who don't know your work to take a look. But it probably doesn't mean that much to people who have read you before. If they really turn on to what you're doing, they look for the name, and they'll buy the book on the basis of that. Like this new Led Zeppelin album packaged in brown paper with "Led Zeppelin" stamped on the front — you buy the name. I like books that are nicely made, and with the exception of Salem's Lot and Night Shift, none of the Doubleday books were especially well made. They have a ragged, machine-produced look to them, as though they were built to fall apart. The Stand is worse that way; it looks like a brick. It's this little, tiny, squatty thing that looks much bigger than it is. The Dead Zone is really nicely put together. It's got a nice cloth binding, and it's just a nice product.

Bhob: With The Dead Zone having climbed so high on the best-seller list...

King: Wonderful. I love it.

Bhob: Have there been any film offers?

King: Lorimar bought it for Sydney Pollack to direct, and it would be produced by Paul Monash, who produced the film of Carrie, and also written by Monash. And if for some reason Monash's screenplay was unacceptable, or Monash had to leave the picture, I'd get second shot. Or at least we're trying to work that detail out. That's not in the deal that we okayed, but we're going to try to get that. They bought it for well in excess of a quarter of a million dollars. They paid good money for it, so I'm hoping to see a front line theatrical film out of it - depending on how fast they move.

And that's the deal.

Bhob: In "'Strawberry Spring" you wrote about Springheel Jack. The few mentions of Springheel Jack that I've run across seem to indicate that he was a mythical British character who was luminous and was witnessed leaping twenty-five or thirty feet.

King: Yeah. That's him! That's him! My Springheel Jack is a cross between Jack the Ripper and a mythical strangler - like Burke and Hare or somebody like that.

Bhob: But you embellished that history?

King: Yeah, right. I did. Robert Bloch has also done some of this embellishing, and he mentions Springheel Jack in a third context. He's like Plastic Man or Superman — a weird folk hero.

Bhob: I think it was a nonfiction UFO book where I first encountered a description of him suggesting -

King: A creature from outer space. [See Jacques Bergier's Extraterrestrial Visitations from Prehistoric Times to the Present, New American Library].

Bhob: What happened to the Night Shift TV anthology pilot planned trilogy of Strawberry "I Know What You Need" and "Battle -

King: It's not going to be done for TV because NBC nixed it... too gruesome, too violent, too intense. It's the atmosphere of TV today; five years ago it would have been done, but the standards and practices people just said, "No." What's going on now is that the production company people have gone to Martin Poll in New York, and he would like to produce it. So we'll see what happens. I don't think anybody's falling over themselves to do it right now.

Bhob: But "Battleground" seems more like a story that would work in a Milton Subotsky film rather than being grouped with the stories set in -

King: The way this works out is that... I can see a lot of possibilities that just can't be realized because people take these options in a harum-scarum way, and then they're cut out. We discussed this with the trilogy for NBC. There's a rooming house in the town, and the hit man from "Battleground"' lives in this rooming house. The premise is that reality is thinner in this town, and things are weird in this one particular place. There are forces which focus on this town and cause things to happen. On the other hand. there's another college story, set on a mythical campus, Horlicks University, called "The Crate." It was published in Gallery [July, 1979) - and that's the third college story. So you have "Strawberry Spring," "The Crate," and "I Know What You Need," which are all really set on the same campus. They are called by different names because I invented Horlicks later. They'd make a beautiful trilogy together, but there's no way that we can do that because George Romero owns "The Crate" and these other people own the other two.

Bhob: Kubrick's film of The Shining reportedly replaces your topiary animals with a hedge maze, an idea you had originally considered. On page 203 of the book, there's a mention of hedge billboards in Vermont. Do these exist and is this what inspired your topiary?

King: They're really there. The idea for the hedge maze is really Kubrick's and not mine. I had considered it, but then I realized it had been done in the movie The Maze [1953] with Richard Carlson, and I rejected the maze idea for that reason. I have no knowledge as to whether or not Kubrick has ever seen that movie or if he'd even considered that or if it just happens to be coincidence.

The billboards advertise some kind of ice cream, they're on Route 2 in Vermont. As you come across this open space where there are no trees, you can look across this rolling meadow to the land which I assume that the ice cream factory owns. The words of the ad have been clipped out of hedges. To heighten the contrast, these hedges have been surrounded with white crushed stone so that the letters just leap right out at you. You know the first time you see them that there's something very peculiar about them, and then you realize, as you get closer, that it may be one of the world's few living signs - because they're hedges. But I got the idea for the topiary from Camden, Maine - where Peyton Place [1957] was filmed. You come down Route I, you go through Camden, and there are several houses there that have clipped shrubs.

They're not clipped into the shapes of animals, but they're clipped into very definite geometric shapes.

There's a hedge that's clipped to look like a diamond. That was my first real experience with the topiary. There is a topiary at Disney World where the hedges are clipped to look like animals, but I saw that long after the book was published. In some ways, I like Kubrick's idea to use a maze. Because it's been pointed out to me — and I think there's some truth to this - that the hedge animals in my novel are the only outward empiric supernatural event that goes on in the book. Everything else can be taken as the hotel actually working on people's minds. That is to say, nothing is going on outwardly. It's all going on inwardly, and it's spreading from Danny to Jack and, finally, to Wendy, who is the least imaginative of the three. But the hedge animals are real, apparently, because they cut open Danny's leg at one point in the book. Later on, when Halloran comes up the mountain, they attack him. They are really, really there. Kubrick told me, and he's told other people as well, that his only basis for taking the hedge animals out was because they would be difficult to do with the special effects — to make it look real.