Roger Christian: Heavy Metal Alchemist

Few figures have left as deep a mark on science fiction cinema as Roger Christian. The Academy Award–winning set decorator helped forge the “used universe” of Star Wars (1977) and the claustrophobic industrial horror of Alien (1979), turning scrap metal and found objects into spaceships and corridors that felt startlingly real. His work not only revolutionized how audiences saw the future on screen, it also resonated with visual storytellers across media, including comics.

Heavy Metal itself published Alien: The Illustrated Story in 1979, Archie Goodwin and Walt Simonson’s captivating adaptation of the film, translating Christian’s lived-in sets into stark, industrial panels. Christian has cited French comics legend Enki Bilal (whose story, Trapped Woman appeared in Heavy Metal in 1986) as a stylistic influence. With Bilal’s BUG now debuting in English in Heavy Metal’s current run, it feels like the perfect moment to revisit the design philosophy of a man whose worlds continue to shape how we imagine the future. This conversation was a powerful reminder of how the world’s greatest illustrated fantasy magazine, and comic art as a whole, has inspired creators across every medium.

HM: What first inspired you to get into set decoration and film design? Were there specific artists, illustrators, or films that shaped your eye?

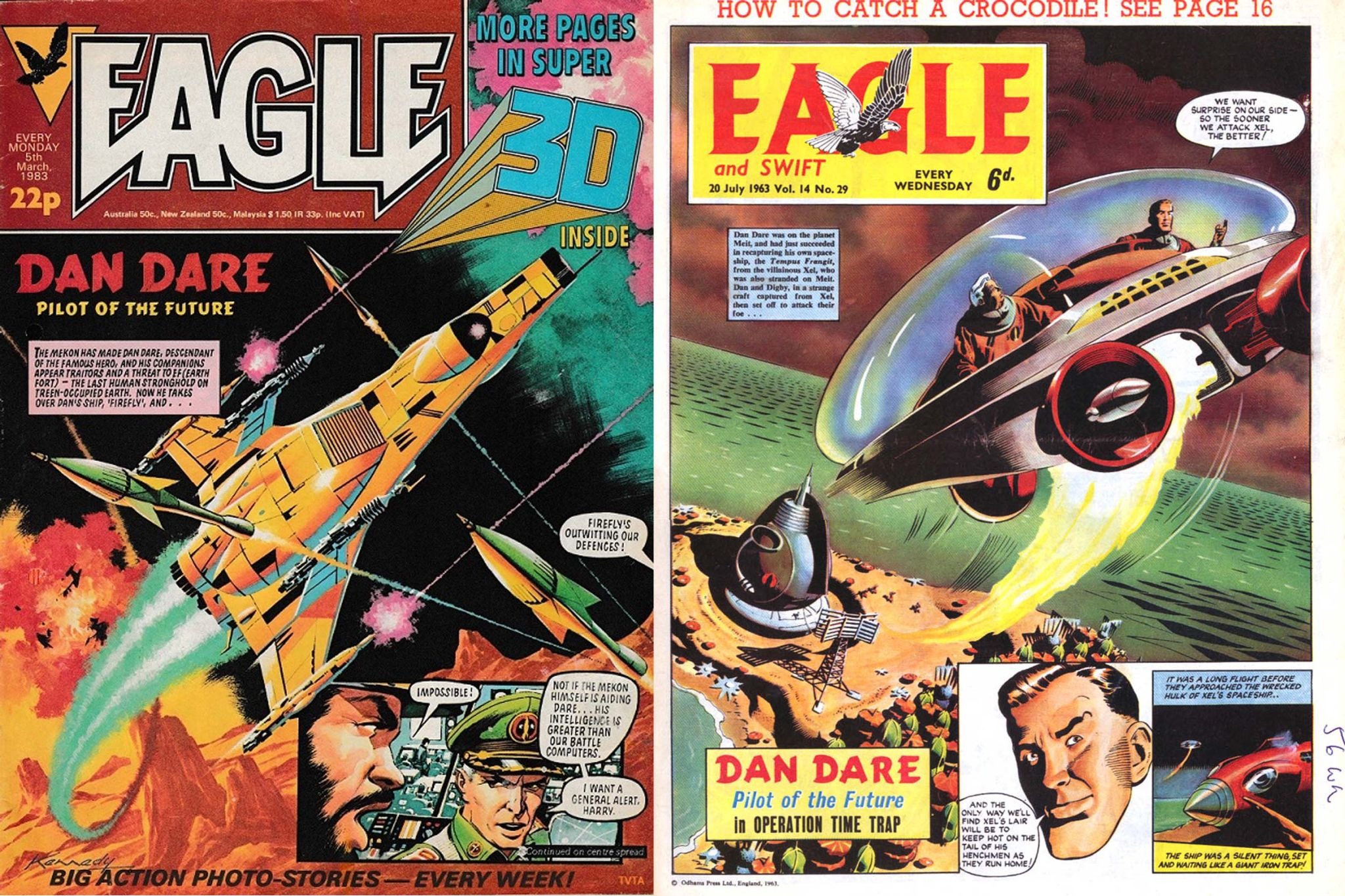

RC: It was a way into an industry I knew nothing about as I’d studied Art, that was suggested as the best way in as I knew nobody. I watched every Kurosawa, Bergman and Tarkofsky movie and with about 10 art theatres in London back then, every European director. I went every week. The original Forbidden Planet store was in Denmark Street back then, and I’d get any interesting graphic novels and comics. This interest came from very young, Dan Dare in the Eagle was my favourite.

HM: Before Star Wars, sci-fi often looked very polished and “shiny.” How did you arrive at the “used universe” aesthetic?

RC: I never connected to any science fiction movies because they looked so artificial, weapons were never realistic, and it seems audiences globally shared my view. I was inspired by the broken spaceship in Solaris and particularly by Alphaville, Jean Luc Godard's science fiction film shot on a Bolex in the streets of Paris. When I was young I used to paint my dinky cars to make them look more real and photograph them in the garden to set up real situations, I guess from there I developed the real, oily and used aesthetic. In my documentary Galaxy Built On Hope, I researched my past as I was born at the end of the war, and London was bombed and wrecked. A flying bomb blew in the windows in our house and I was covered in red, I was 6 months old. They thought I was dead, it was a sacred bottle of ketchup that exploded. My earliest memories would have been of devastated streets and maybe this became a subconscious influence as I connected immediately later to Bilal's graphic novel vision of devastated London in Trapped Woman.

HM: Heavy Metal published the 1979 graphic-novel adaptation Alien: The Illustrated Story, scripted by Archie Goodwin and drawn by Walt Simonson, which was the very first comic adaptation from the Alien franchise. How did you feel the comic translation handled the sets and atmosphere you’d helped build on the film? Were there panels or pages that captured something you were proud of, or that surprised you?

RC: They’d carefully soaked up the claustrophobic atmosphere of my interiors and the colour palette of a space truck I’d set out to create with Ridley. On set Ridley used smoke to create a uniform used look that desaturated the colour, especially with the actors faces, that I believe helped the audience accept this as an almost documentary like movie it was so real. I think the coloured faces and backgrounds took away a small amount of that believable world.

HM: When you look back at the interiors of the Millennium Falcon or the Nostromo, are there lessons or ideas from your design approach that you think today’s set designers or illustrators could still learn from?

RC: For sure yes, very important to me was the way we built up the scrap and pipework to have authenticity. You can’t just stick pieces randomly, it has to be done with an aesthetic of what looks real and works mechanically. I had been in a submarine and watched bombers like B 52’s that are layered with detail, and I tried to emulate this. Neither of the interiors were drawn up by the draughtsmen, I relied on my instinct to build layers of aircraft junk, water pipes and cables, and switch panels that the SFX boys built for me and I kept going until it looked right.

HM: You’ve said that Enki Bilal’s work, specifically Trapped Woman (Published in English in Heavy Metal, Fall 1986), was a big stylistic influence for you. Can you say more about what specifically in Bilal’s work left an impression on you?

RC: Trapped Woman had a female heroine and like George Lucas making Princess Leia a feisty princess fight for the rebellion, it was rare back then to have female superheroes if you like to call them that. His muted and layered colour palette showing Destroyed London was atmospheric and had a science fiction view of the future that seemed so real.

HM: Bilal’s series BUG is appearing in the revived Heavy Metal and is being presented in English for the first time in the magazine’s current run. Did you get a chance to see BUG in the current issues?

RC: Awesome, his muted colours and detail are a refreshing reminder of Bilal’s influence in the science fiction world and I’m so happy to see him recognized again in the mainstream graphic novel world. Too few know him when I mention his influence except hard core enthusiast and collectors.

HM: What message do you have for other creators, whether they’re filmmakers, comic artists, or narrative worldbuilders?

RC: Find your story. That's what matters. Blade Runner aesthetic comes from Ridley Scott growing up in Newcastle, an industrial hub in the UK. Smoke stack towers with flames and smoke rising into the atmosphere, and rain, inspired the look of Blade Runner, and the muted colour palette of Alien. Mine came from growing up in war damaged London streets and my love of Arthurian legends which inspired the look of my first film as a director, Black Angel. Then applied to my favourite Feature film I directed, Nostradamus. Filming in war damaged Romania right after the revolution gave credence and authenticity to the look of the movie. Nostradamus was recognized in Spain and France at the time as the most authentic portrayal of Medieval times in cinema.

For those who want to journey further into the void, Roger Christian’s autobiography Cinema Alchemist is the star map. From forging the first lightsaber to charting the shadowed corridors of the Nostromo in Alien and the haunting realm of Black Angel, Christian unveils the secrets of a world-builder who reshaped science fiction. With forewords by George Lucas, David West Reynolds, and J.W. Rinzler, it reads like a record of an era of discovery that we’re unlikely to experience again, where scrap became starships.

Roger Christian: Heavy Metal Alchemist

Few figures have left as deep a mark on science fiction cinema as Roger Christian. The Academy Award–winning set decorator helped forge the “used universe” of Star Wars (1977) and the claustrophobic industrial horror of Alien (1979), turning scrap metal and found objects into spaceships and corridors that felt startlingly real. His work not only revolutionized how audiences saw the future on screen, it also resonated with visual storytellers across media, including comics.

Heavy Metal itself published Alien: The Illustrated Story in 1979, Archie Goodwin and Walt Simonson’s captivating adaptation of the film, translating Christian’s lived-in sets into stark, industrial panels. Christian has cited French comics legend Enki Bilal (whose story, Trapped Woman appeared in Heavy Metal in 1986) as a stylistic influence. With Bilal’s BUG now debuting in English in Heavy Metal’s current run, it feels like the perfect moment to revisit the design philosophy of a man whose worlds continue to shape how we imagine the future. This conversation was a powerful reminder of how the world’s greatest illustrated fantasy magazine, and comic art as a whole, has inspired creators across every medium.

HM: What first inspired you to get into set decoration and film design? Were there specific artists, illustrators, or films that shaped your eye?

RC: It was a way into an industry I knew nothing about as I’d studied Art, that was suggested as the best way in as I knew nobody. I watched every Kurosawa, Bergman and Tarkofsky movie and with about 10 art theatres in London back then, every European director. I went every week. The original Forbidden Planet store was in Denmark Street back then, and I’d get any interesting graphic novels and comics. This interest came from very young, Dan Dare in the Eagle was my favourite.

HM: Before Star Wars, sci-fi often looked very polished and “shiny.” How did you arrive at the “used universe” aesthetic?

RC: I never connected to any science fiction movies because they looked so artificial, weapons were never realistic, and it seems audiences globally shared my view. I was inspired by the broken spaceship in Solaris and particularly by Alphaville, Jean Luc Godard's science fiction film shot on a Bolex in the streets of Paris. When I was young I used to paint my dinky cars to make them look more real and photograph them in the garden to set up real situations, I guess from there I developed the real, oily and used aesthetic. In my documentary Galaxy Built On Hope, I researched my past as I was born at the end of the war, and London was bombed and wrecked. A flying bomb blew in the windows in our house and I was covered in red, I was 6 months old. They thought I was dead, it was a sacred bottle of ketchup that exploded. My earliest memories would have been of devastated streets and maybe this became a subconscious influence as I connected immediately later to Bilal's graphic novel vision of devastated London in Trapped Woman.

HM: Heavy Metal published the 1979 graphic-novel adaptation Alien: The Illustrated Story, scripted by Archie Goodwin and drawn by Walt Simonson, which was the very first comic adaptation from the Alien franchise. How did you feel the comic translation handled the sets and atmosphere you’d helped build on the film? Were there panels or pages that captured something you were proud of, or that surprised you?

RC: They’d carefully soaked up the claustrophobic atmosphere of my interiors and the colour palette of a space truck I’d set out to create with Ridley. On set Ridley used smoke to create a uniform used look that desaturated the colour, especially with the actors faces, that I believe helped the audience accept this as an almost documentary like movie it was so real. I think the coloured faces and backgrounds took away a small amount of that believable world.

HM: When you look back at the interiors of the Millennium Falcon or the Nostromo, are there lessons or ideas from your design approach that you think today’s set designers or illustrators could still learn from?

RC: For sure yes, very important to me was the way we built up the scrap and pipework to have authenticity. You can’t just stick pieces randomly, it has to be done with an aesthetic of what looks real and works mechanically. I had been in a submarine and watched bombers like B 52’s that are layered with detail, and I tried to emulate this. Neither of the interiors were drawn up by the draughtsmen, I relied on my instinct to build layers of aircraft junk, water pipes and cables, and switch panels that the SFX boys built for me and I kept going until it looked right.

HM: You’ve said that Enki Bilal’s work, specifically Trapped Woman (Published in English in Heavy Metal, Fall 1986), was a big stylistic influence for you. Can you say more about what specifically in Bilal’s work left an impression on you?

RC: Trapped Woman had a female heroine and like George Lucas making Princess Leia a feisty princess fight for the rebellion, it was rare back then to have female superheroes if you like to call them that. His muted and layered colour palette showing Destroyed London was atmospheric and had a science fiction view of the future that seemed so real.

HM: Bilal’s series BUG is appearing in the revived Heavy Metal and is being presented in English for the first time in the magazine’s current run. Did you get a chance to see BUG in the current issues?

RC: Awesome, his muted colours and detail are a refreshing reminder of Bilal’s influence in the science fiction world and I’m so happy to see him recognized again in the mainstream graphic novel world. Too few know him when I mention his influence except hard core enthusiast and collectors.

HM: What message do you have for other creators, whether they’re filmmakers, comic artists, or narrative worldbuilders?

RC: Find your story. That's what matters. Blade Runner aesthetic comes from Ridley Scott growing up in Newcastle, an industrial hub in the UK. Smoke stack towers with flames and smoke rising into the atmosphere, and rain, inspired the look of Blade Runner, and the muted colour palette of Alien. Mine came from growing up in war damaged London streets and my love of Arthurian legends which inspired the look of my first film as a director, Black Angel. Then applied to my favourite Feature film I directed, Nostradamus. Filming in war damaged Romania right after the revolution gave credence and authenticity to the look of the movie. Nostradamus was recognized in Spain and France at the time as the most authentic portrayal of Medieval times in cinema.

For those who want to journey further into the void, Roger Christian’s autobiography Cinema Alchemist is the star map. From forging the first lightsaber to charting the shadowed corridors of the Nostromo in Alien and the haunting realm of Black Angel, Christian unveils the secrets of a world-builder who reshaped science fiction. With forewords by George Lucas, David West Reynolds, and J.W. Rinzler, it reads like a record of an era of discovery that we’re unlikely to experience again, where scrap became starships.

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

Few figures have left as deep a mark on science fiction cinema as Roger Christian. The Academy Award–winning set decorator helped forge the “used universe” of Star Wars (1977) and the claustrophobic industrial horror of Alien (1979), turning scrap metal and found objects into spaceships and corridors that felt startlingly real. His work not only revolutionized how audiences saw the future on screen, it also resonated with visual storytellers across media, including comics.

Heavy Metal itself published Alien: The Illustrated Story in 1979, Archie Goodwin and Walt Simonson’s captivating adaptation of the film, translating Christian’s lived-in sets into stark, industrial panels. Christian has cited French comics legend Enki Bilal (whose story, Trapped Woman appeared in Heavy Metal in 1986) as a stylistic influence. With Bilal’s BUG now debuting in English in Heavy Metal’s current run, it feels like the perfect moment to revisit the design philosophy of a man whose worlds continue to shape how we imagine the future. This conversation was a powerful reminder of how the world’s greatest illustrated fantasy magazine, and comic art as a whole, has inspired creators across every medium.

HM: What first inspired you to get into set decoration and film design? Were there specific artists, illustrators, or films that shaped your eye?

RC: It was a way into an industry I knew nothing about as I’d studied Art, that was suggested as the best way in as I knew nobody. I watched every Kurosawa, Bergman and Tarkofsky movie and with about 10 art theatres in London back then, every European director. I went every week. The original Forbidden Planet store was in Denmark Street back then, and I’d get any interesting graphic novels and comics. This interest came from very young, Dan Dare in the Eagle was my favourite.

HM: Before Star Wars, sci-fi often looked very polished and “shiny.” How did you arrive at the “used universe” aesthetic?

RC: I never connected to any science fiction movies because they looked so artificial, weapons were never realistic, and it seems audiences globally shared my view. I was inspired by the broken spaceship in Solaris and particularly by Alphaville, Jean Luc Godard's science fiction film shot on a Bolex in the streets of Paris. When I was young I used to paint my dinky cars to make them look more real and photograph them in the garden to set up real situations, I guess from there I developed the real, oily and used aesthetic. In my documentary Galaxy Built On Hope, I researched my past as I was born at the end of the war, and London was bombed and wrecked. A flying bomb blew in the windows in our house and I was covered in red, I was 6 months old. They thought I was dead, it was a sacred bottle of ketchup that exploded. My earliest memories would have been of devastated streets and maybe this became a subconscious influence as I connected immediately later to Bilal's graphic novel vision of devastated London in Trapped Woman.

HM: Heavy Metal published the 1979 graphic-novel adaptation Alien: The Illustrated Story, scripted by Archie Goodwin and drawn by Walt Simonson, which was the very first comic adaptation from the Alien franchise. How did you feel the comic translation handled the sets and atmosphere you’d helped build on the film? Were there panels or pages that captured something you were proud of, or that surprised you?

RC: They’d carefully soaked up the claustrophobic atmosphere of my interiors and the colour palette of a space truck I’d set out to create with Ridley. On set Ridley used smoke to create a uniform used look that desaturated the colour, especially with the actors faces, that I believe helped the audience accept this as an almost documentary like movie it was so real. I think the coloured faces and backgrounds took away a small amount of that believable world.

HM: When you look back at the interiors of the Millennium Falcon or the Nostromo, are there lessons or ideas from your design approach that you think today’s set designers or illustrators could still learn from?

RC: For sure yes, very important to me was the way we built up the scrap and pipework to have authenticity. You can’t just stick pieces randomly, it has to be done with an aesthetic of what looks real and works mechanically. I had been in a submarine and watched bombers like B 52’s that are layered with detail, and I tried to emulate this. Neither of the interiors were drawn up by the draughtsmen, I relied on my instinct to build layers of aircraft junk, water pipes and cables, and switch panels that the SFX boys built for me and I kept going until it looked right.

HM: You’ve said that Enki Bilal’s work, specifically Trapped Woman (Published in English in Heavy Metal, Fall 1986), was a big stylistic influence for you. Can you say more about what specifically in Bilal’s work left an impression on you?

RC: Trapped Woman had a female heroine and like George Lucas making Princess Leia a feisty princess fight for the rebellion, it was rare back then to have female superheroes if you like to call them that. His muted and layered colour palette showing Destroyed London was atmospheric and had a science fiction view of the future that seemed so real.

HM: Bilal’s series BUG is appearing in the revived Heavy Metal and is being presented in English for the first time in the magazine’s current run. Did you get a chance to see BUG in the current issues?

RC: Awesome, his muted colours and detail are a refreshing reminder of Bilal’s influence in the science fiction world and I’m so happy to see him recognized again in the mainstream graphic novel world. Too few know him when I mention his influence except hard core enthusiast and collectors.

HM: What message do you have for other creators, whether they’re filmmakers, comic artists, or narrative worldbuilders?

RC: Find your story. That's what matters. Blade Runner aesthetic comes from Ridley Scott growing up in Newcastle, an industrial hub in the UK. Smoke stack towers with flames and smoke rising into the atmosphere, and rain, inspired the look of Blade Runner, and the muted colour palette of Alien. Mine came from growing up in war damaged London streets and my love of Arthurian legends which inspired the look of my first film as a director, Black Angel. Then applied to my favourite Feature film I directed, Nostradamus. Filming in war damaged Romania right after the revolution gave credence and authenticity to the look of the movie. Nostradamus was recognized in Spain and France at the time as the most authentic portrayal of Medieval times in cinema.

For those who want to journey further into the void, Roger Christian’s autobiography Cinema Alchemist is the star map. From forging the first lightsaber to charting the shadowed corridors of the Nostromo in Alien and the haunting realm of Black Angel, Christian unveils the secrets of a world-builder who reshaped science fiction. With forewords by George Lucas, David West Reynolds, and J.W. Rinzler, it reads like a record of an era of discovery that we’re unlikely to experience again, where scrap became starships.