SEAN ANDREW MURRAY Gallery

Interview by Hannah Means-Shannon

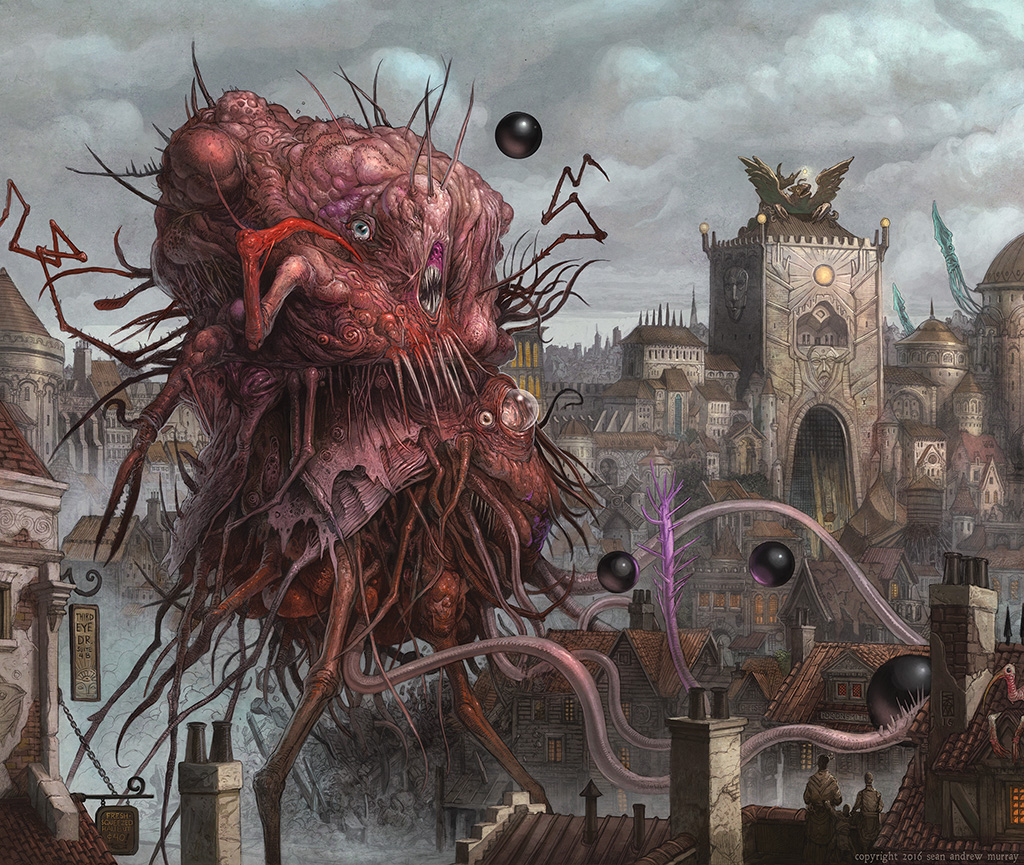

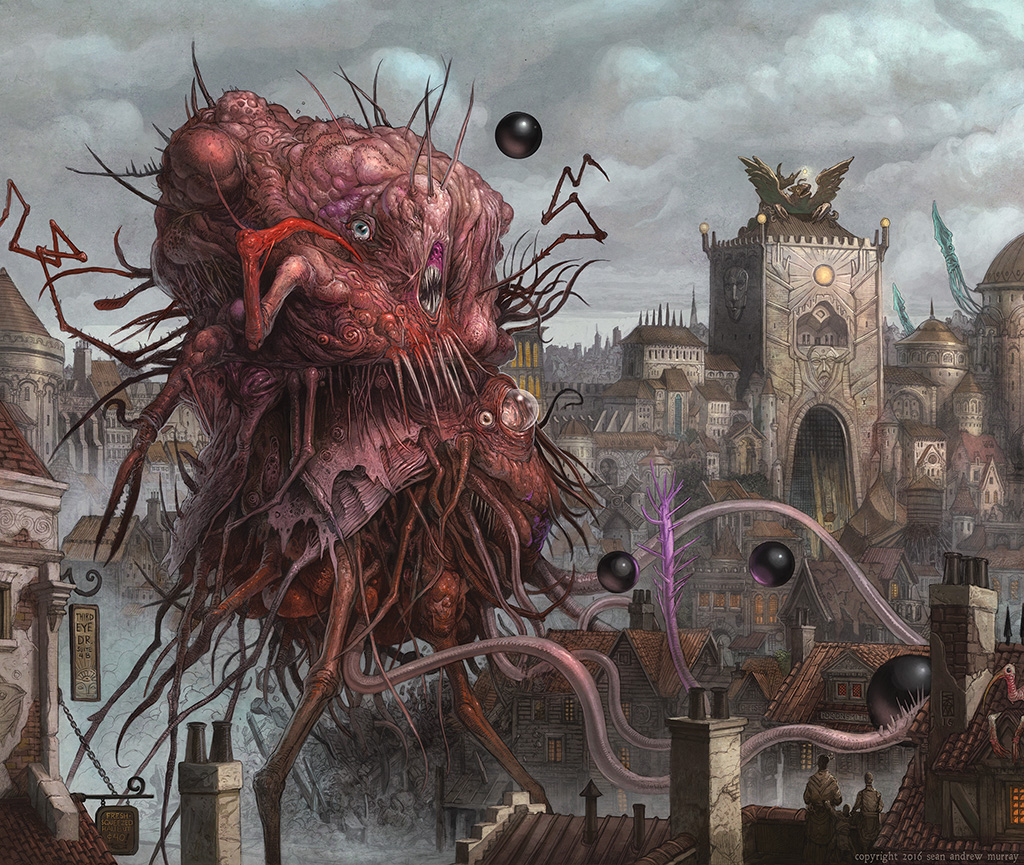

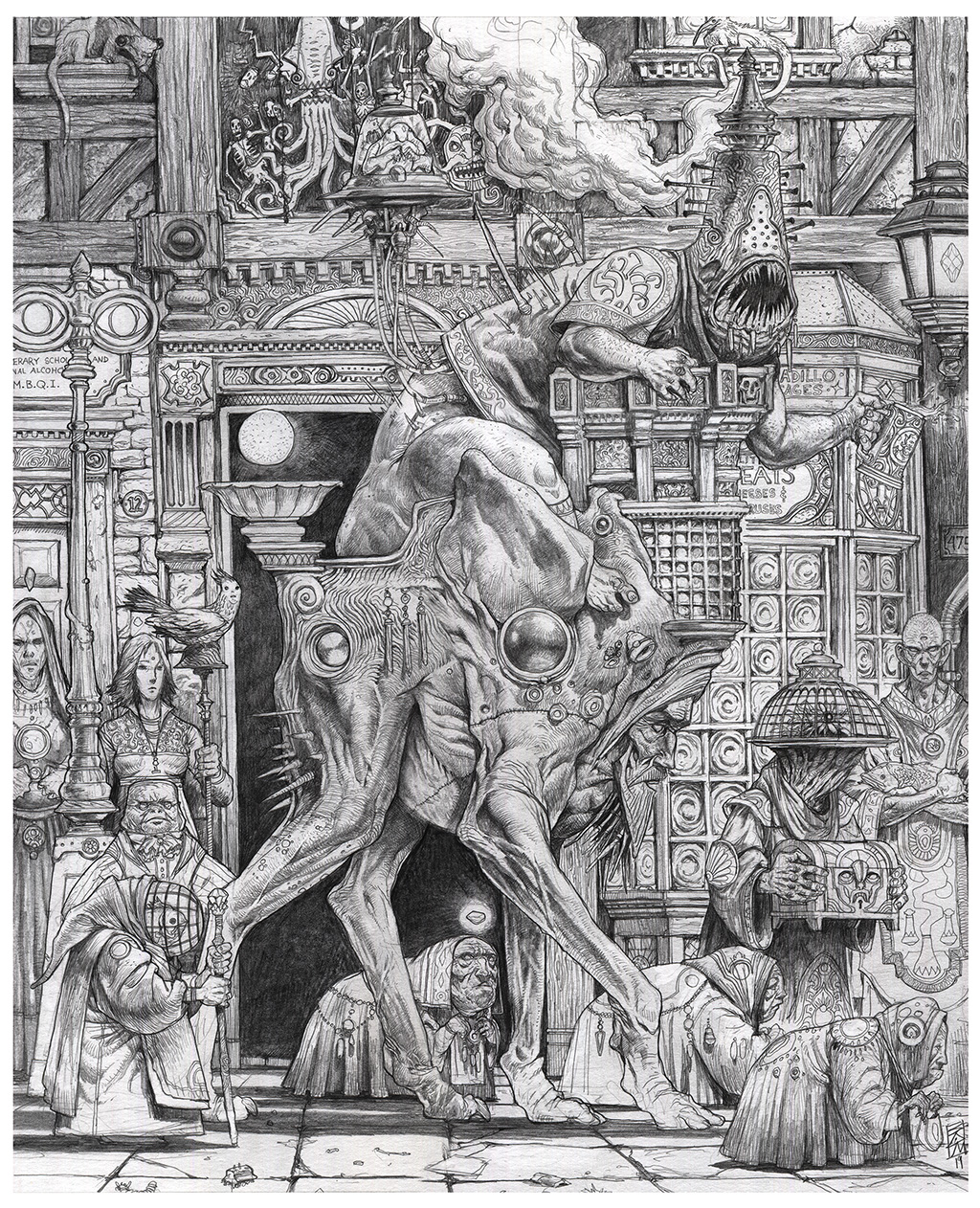

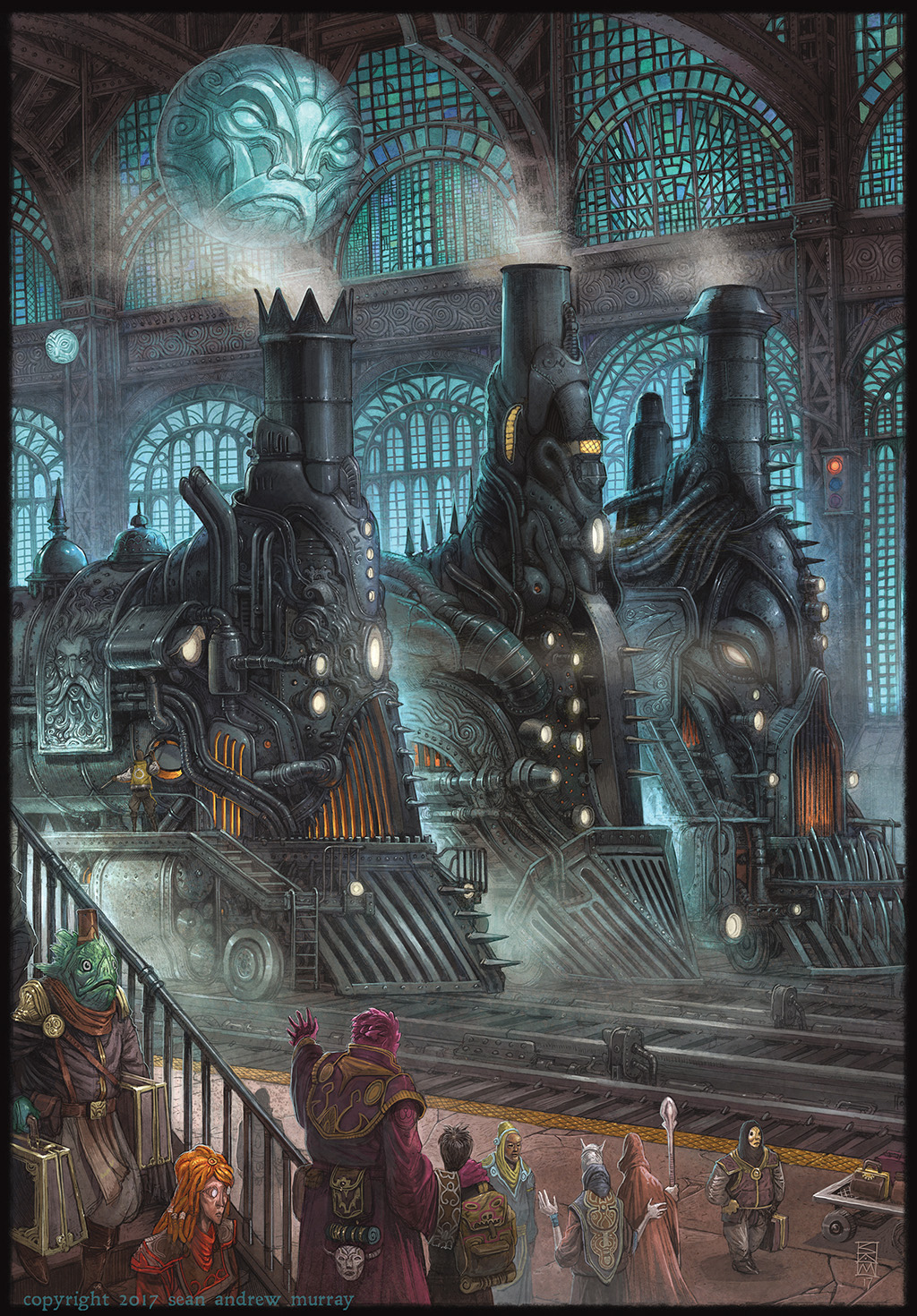

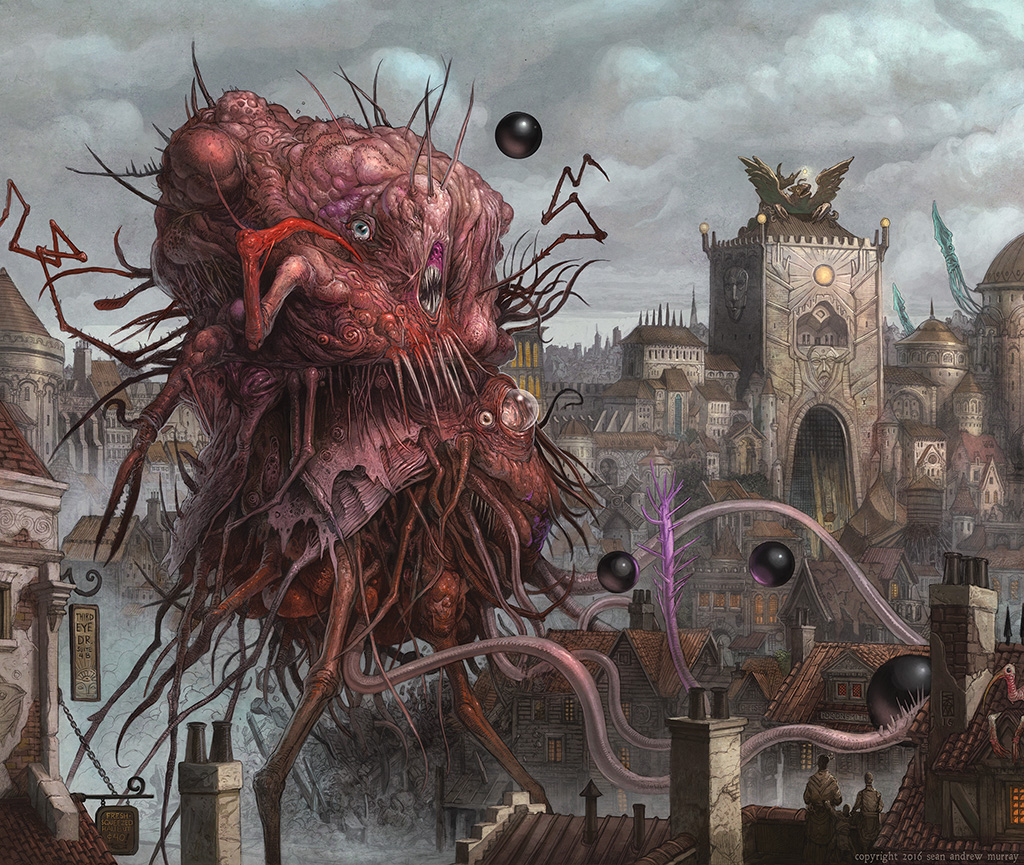

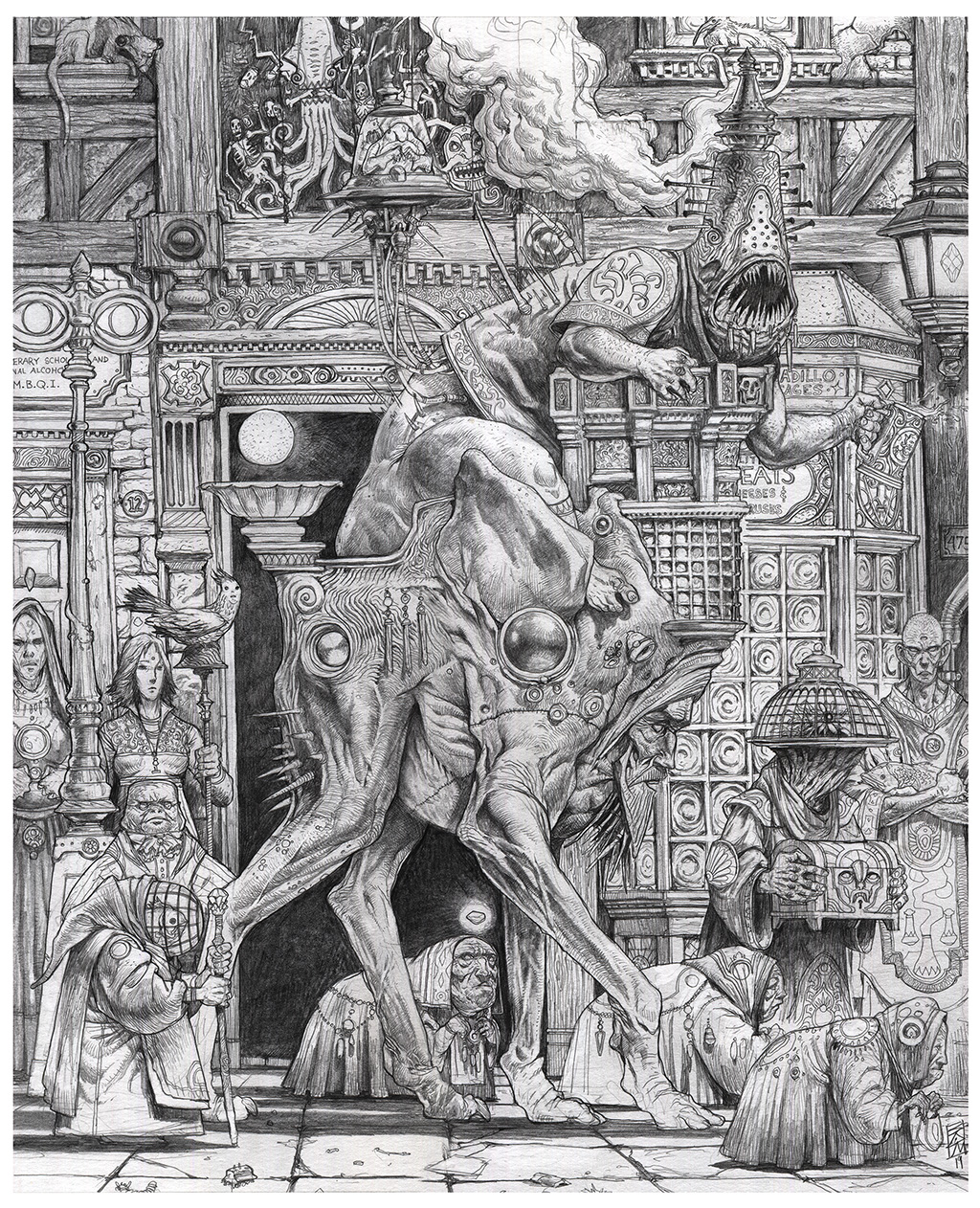

One of this issue #299's cover artists, Sean Andrew Murray, has been quietly building a wealth of detail into a world that has the feeling of a “found” location, a discovery of a reality as nuanced as an ancient European capitol at the end of the middle ages. Wandering down its streets only prompts more questions, and meeting each of its denizens opens up new concepts in the relationship between magic and religious perspectives for these beings. “Gateway” is a place and a phenomenon, continuously evolving for Murray, whose other work includes concept art video games, tabletop gaming, music, film, TV, and teaching the crafts of illustration and world-building.

You can encounter “Gateway” through Murray’s crowdfunded books, expansion into tabletop gaming, and now, into 3D sculpture via one of his clients, Sideshow Collectibles. Wander into “Gateway” and you may never find your way out, most likely because you simply don’t want to.

Heavy Metal: Do you feel that you have a certain personal aesthetic in your work, or do you find that idea limiting?

Sean Andrew Murray: I acknowledge that my work comes across as having an aesthetic, but I like to think that it isn’t a result of overly-calculated choice-making, but rather is an extension of my identity as an artist. People often like to comment on my social media feeds about what my work reminds them of, and I used to get a little annoyed at these kinds of comments. But then I began embracing them when I realized that it would be silly for me to deny that I am a product of my influences – to claim to be entirely original is disingenuous at best.

The only time having an aesthetic is limiting is when it doesn’t come from an honest place. Sometimes it’s hard to know when your work is honest or not - perhaps it is a constant struggle - but I find that the more you embrace the ideas that may seem a little scary, risky or weird, the more you begin narrow in on that inner voice, however elusive it might be.

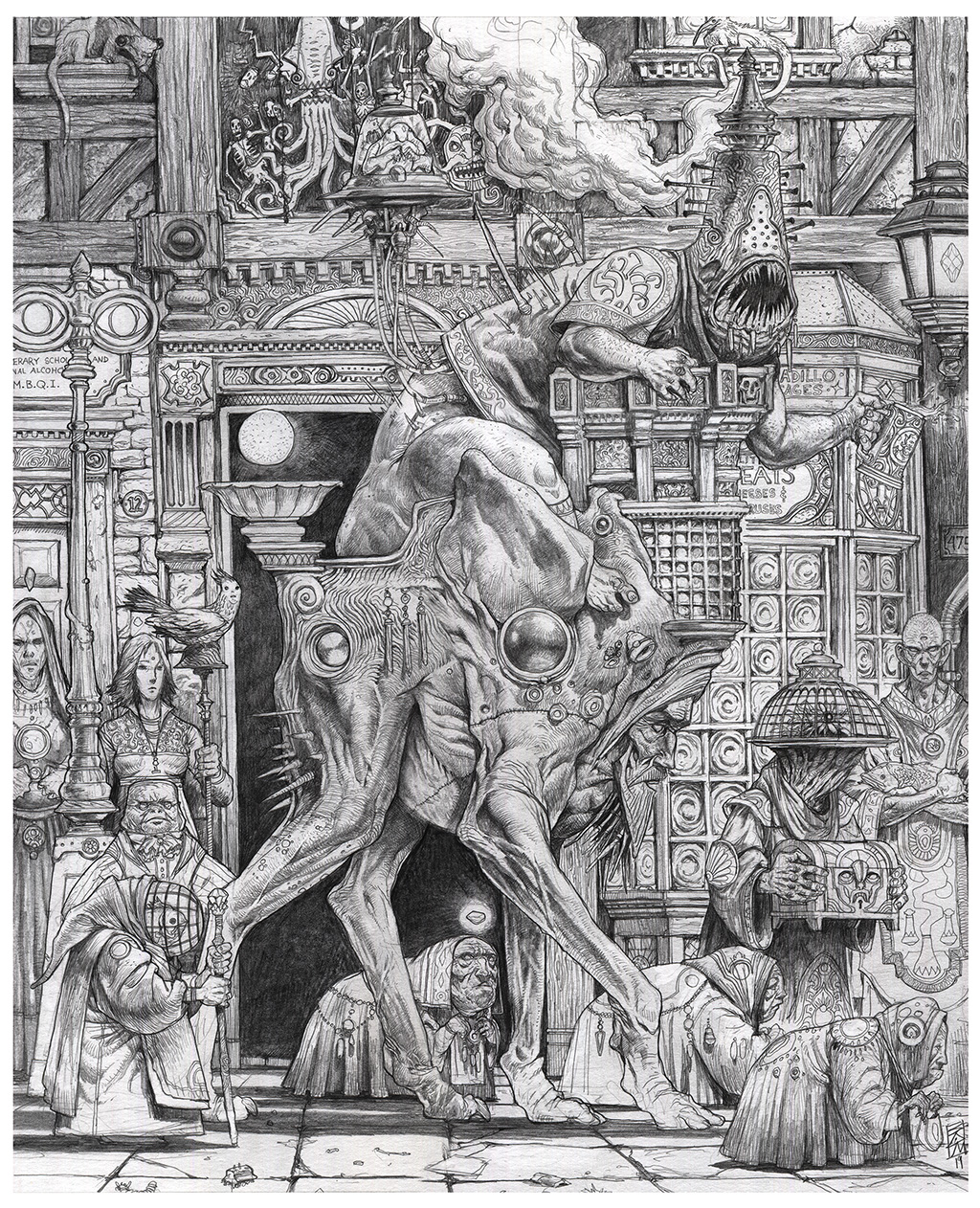

HM: What drives you toward creating texture and softer line-work rather than harder edges?

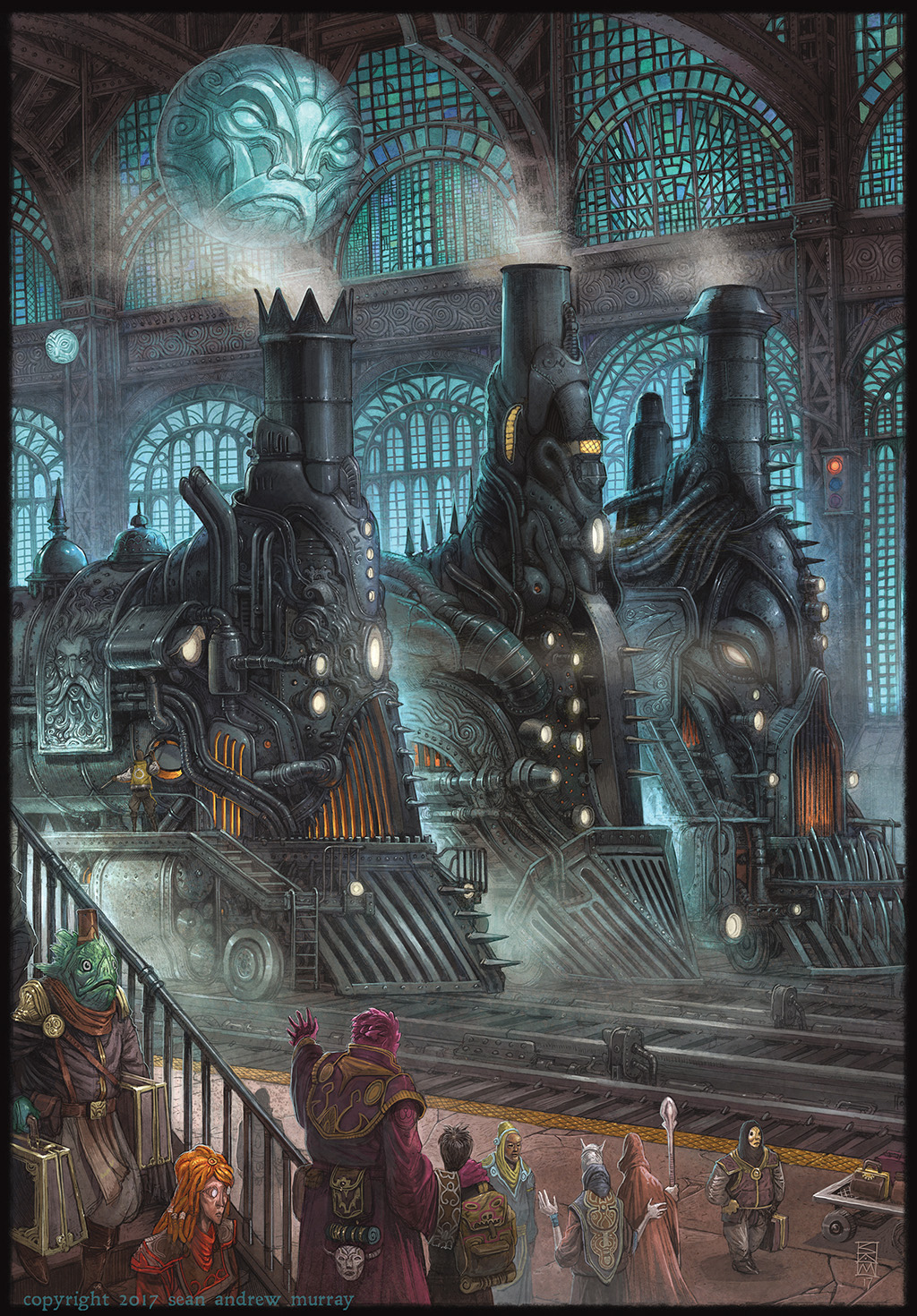

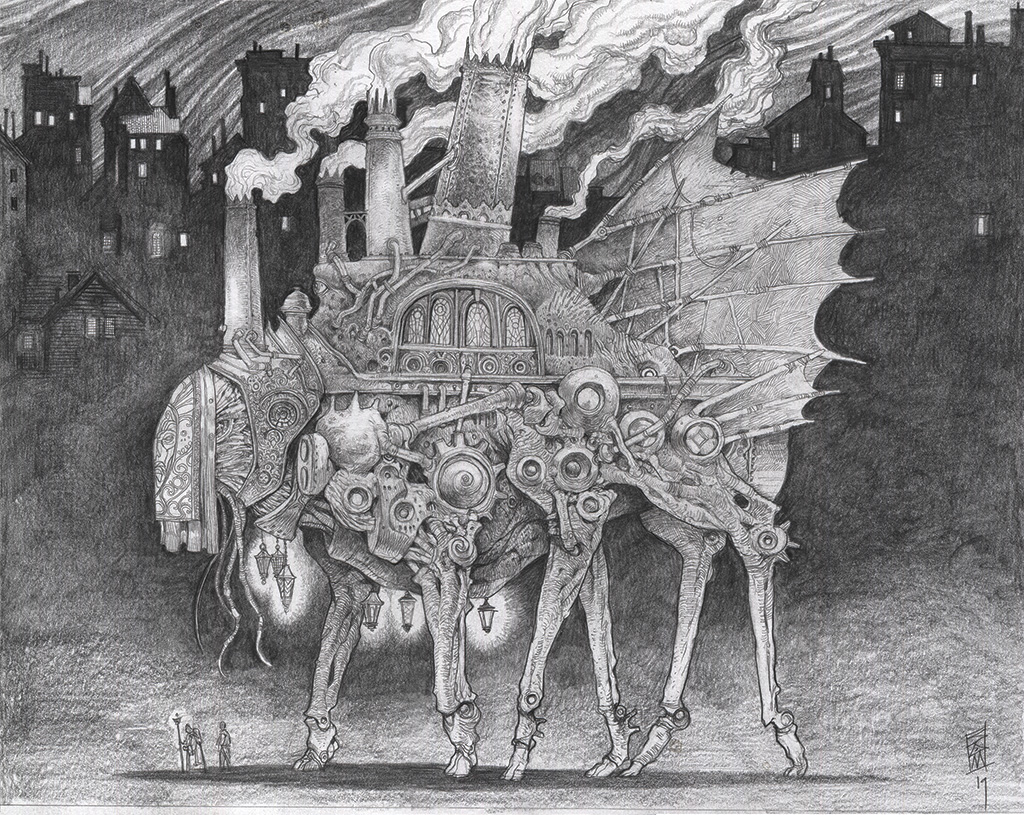

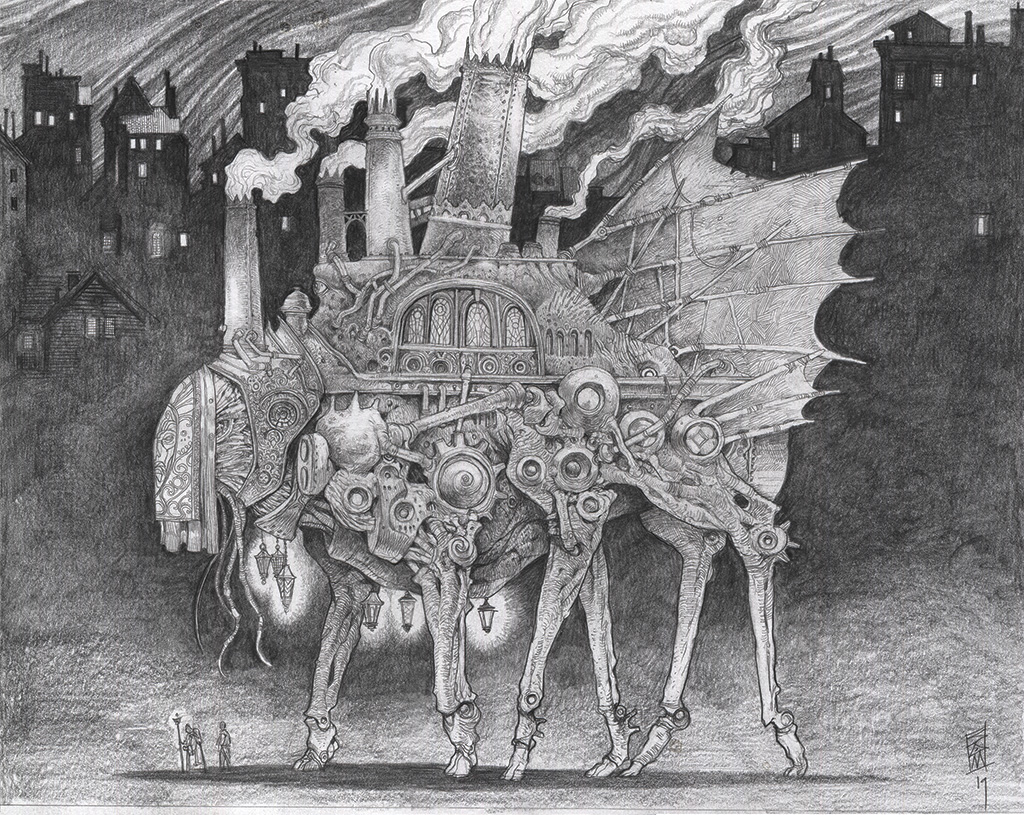

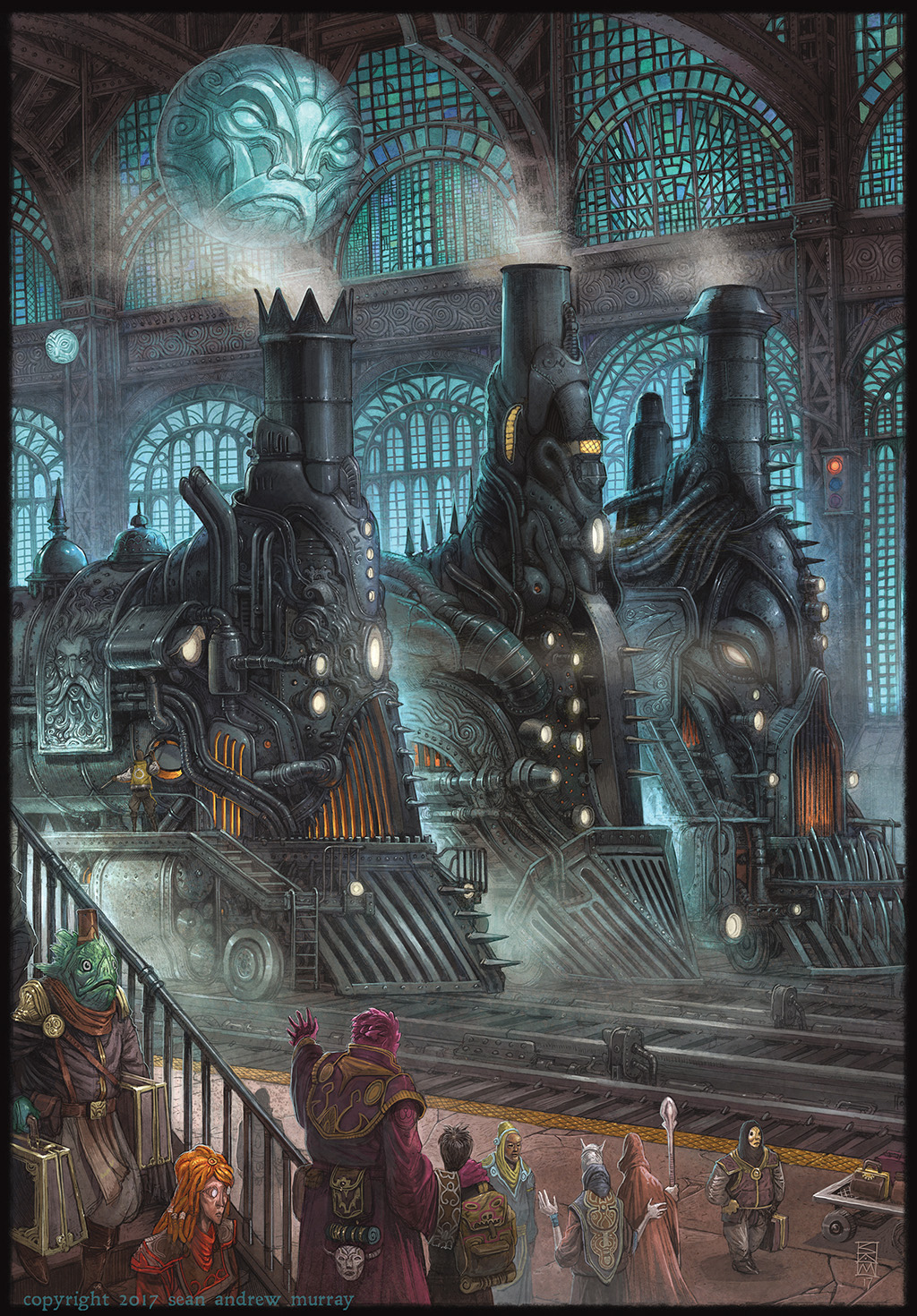

SAM: Organic shapes are just more compelling to me I suppose – even, or perhaps especially, when it comes to architecture and vehicles, etc. That mix of the functional with the organic has always captured my imagination.That’s why I think gravitate to artists like Moebius, Miyazaki, Ian Miller, Arthur Rackham, Bosch, etc. Don’t get me wrong, I love designing spaceships and futuristic vehicles, it’s just that I rarely design them to be symmetrical or hard-surfaced!

I love and admire the work of Ralph MacQuarrie and Syd Mead – their genius brought an unforgettable vision to modern science-fiction and was part of my formative years as a young consumer of popular culture. But their aesthetic and approach to design isn’t something that I feel I can personally achieve in my own work. So, I look for more organic forms.

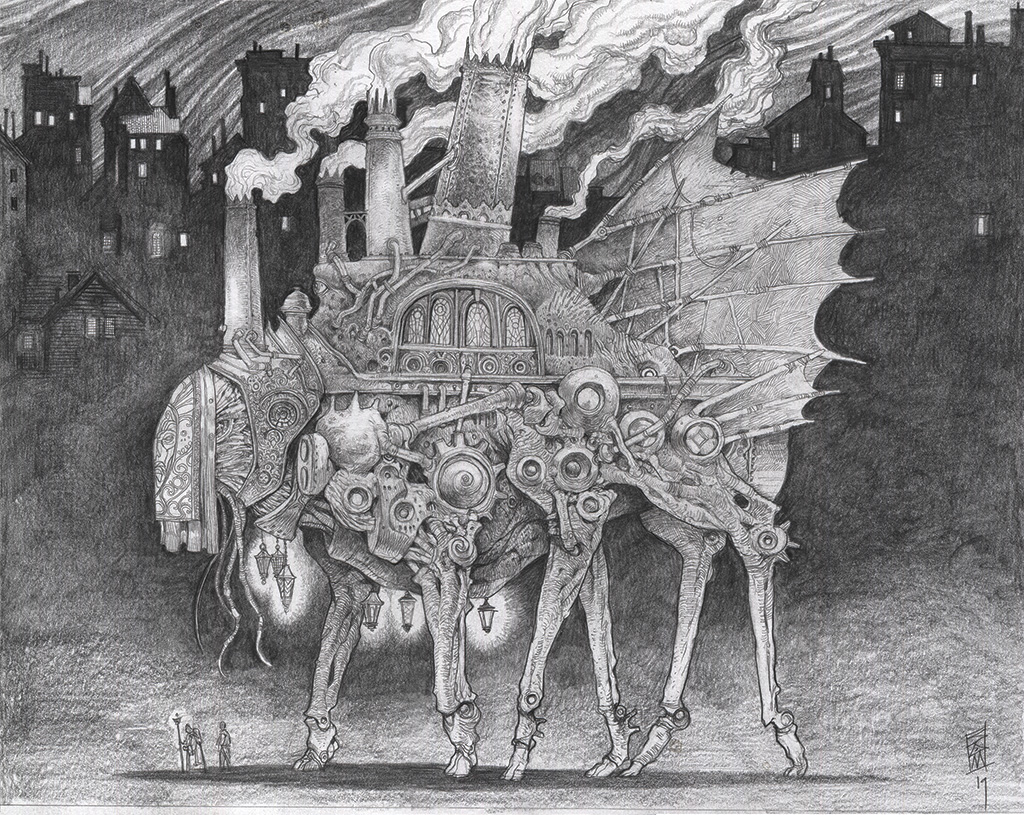

Students who are better at character work than they are at environments often ask me how to design interesting architecture and my response is always the same: approach it the SAME way you design an awesome character. Think about shape, personality, and emotion. I like imagining buildings as living things that could, at any moment, just get up and walk off like a huge elephant or giraffe or float off into the clouds like a jellyfish under the water. I also love the idea of organic or ancient unexplainable forces intermingling with architectural forms to create something that is neither entirely deliberate, nor entirely natural.

HM: How important is it to you for a world in an image to feel “lived in”?

SAM: It is the MOST important thing. “Suspension of disbelief” is all about that feeling of familiarity, which can be applied to any project, no matter how alien the setting. This is a drum I am constantly beating with people who ask me for advice on world-building. How many times have we seen a fantasy piece with a castle that looks like it was built yesterday? It’s not credible! But when you see a castle that looks like it was built over a long period of time by multiple generations of inhabitants, and through periods of war, and plague, and regime change, then that’s when it starts to feel like a real place.

I love the convergence of travel and a passion for local history – when I visit new places, I look for unique stories surrounding that place. For example: San Gimignano in Tuscany, Italy was once known as the “Town of Fine Towers” because at one point its residents were trying to out-do one another with who could build the tallest tower in town. Eventually it got so out of hand that the local magistrates had to pass building codes to put an end to it. All places have stories, and it’s those unique stories that help us believe in the illusion.

HM: When working on a commercial project, how different is that creative mindset for you than when you’re working on something like “Gateway”?

SAM: It depends on the project. These days I have been trying to be a bit pickier about the projects I take on, because sometimes it is not obvious when I take a job whether or not it will be something I can really sink my teeth into. I can sometimes convince myself that I might enjoy it, when there is probably a quieter part of my brain that is saying: “Don’t do it!”. Projects that involve a lot of pre-determined assets are usually not my favorite jobs – I get bogged down by the specifics and the process doesn’t flow as well as when I am working on my own self-driven work.

When creating a personal piece, I usually start with only a vague notion of where I want to go – I like to let the process of drawing itself guide the concept. I am muchmore interested in client work that involves designing new things or when theart direction is more notional rather than direct. One of my favorite clients Ihave worked for in the past is Sideshow Collectibles, especially their “Courtof the Dead” property… that really felt like working on my own stuff.

HM: If you’re creating something for a gaming world, is it concept-art with single image ideas, or is there action involved, like storyboarding?

SAM: Usually the former. I am either not a very good storyboard artist, or it’s just not something I enjoy doing on a regular basis, although I have done it for various game and film projects in the past. I prefer drawing new things and exploring new concepts each time I set pencil to paper. Something about re-drawing the same faces or characters over and over again just puts all these mental roadblocks in front of me, so it becomes more of a chore than a joy. Believe me, I would love to love storyboarding, but I guess it’s just not my thing.

HM: Have you ever created for 3D products like statuary? If so, what kind of thinking goes into making that a reality?

SAM: I have! Recently I partnered with two INCREDIBLE sculptors, Sazen Lee and David Zhou, to produce a series of collectibles based on my personal IP brand: “Gateway”. The concept behind it is that we are creating objects that you might actually find in a wizard’s shop in the city of Gateway, we are calling it the “Gateway: Collector” series. The first one is available right now on Sideshow’s website. It’s called “The Lamp of the GreatFish”, and it’s based off a piece I did several years back of a huge fish headsticking out of the top of a temple, combined with street lamps I designed for Gateway that use severed phosphorescent fish heads floating in a bowl of water to create light. One of the pieces we have created that has yet to be release is based on my concept of “The Elusive Birdfish.” This will have a little crank on it that you turn to make the fins, tail and mouth of the bird-fish move – it’s really neat!

HM: You have some very specific ideas about world-building, I think, drawing from your teaching life. Are there any really big “do’s” and“don’ts”?

SAM: Ha ha, yes, I do have lots of ideas about world-building, but I probably don’t have enough room in this article to express them all! There are, however, a few key “mantras” that I try to stick to. One of the most important ones is that you really have to be passionate about learning more about the world around you before you can create worlds that other people will find interesting. There is so much inspiration in science, nature, archeology, engineering, history, etc. There’s such an endless well of inspiration to draw from that you would be foolish not to take advantage of all those free ideas! Get outside of your bubble and explore the world, experience new things, read books about stuff you know nothing about, watch documentaries or listen to interesting podcasts, etc.

Another important thing to keep in mind is that world-building should be an on going anditerative process that evolves over time and reacts to both your involvement and the involvement of your audience. That’s why I advise people to start small – don’t try to design the entire galactic empire all in one go. Start with a single planet, or better yet, start with a small town on that one planet and spend some time there - explore it, get to know it intimately. The work you do there with be the springboard for the rest of the universe. Share it with your audience earlier than you think! It’s extremely helpful to see how people react and respond to your ideas before setting things in stone, so to speak. The momentum of an excited audience that has been bought in to what you are creating can help guide you towards interesting solutions faster than if you agonize about it without the benefit of knowing if anyone is interested in the first place!

HM: Gateway has been your personal world for a long time. What does it mean to you and what remains to be explored for you, as an artist, and for the fans that you bring with you?

SAM: I think of Gateway as a life-long project at this point. I have been with it, or rather it has been with me, for so long now that I don’t think there is a point at which I will say: “I’m done.” When I am drawing for myself, the images tend mostly towards envisioning new characters and corners of Gateway. I started thinking about it as a response to what I felt was a very conservative genre: fantasy. Although I believe this has changed since those early days, I used to feel as if the fantasy genre, which I love, was mostly populated with Tolkien clones, which didn’t make sense to me because Tolkien already made the best version of Middle Earth, so why try to re-make it?

I didn’t think it was fair that science fiction could have bars full of diverse, bizarre creatures from far-flung places, but inns in fantasy worlds always had the same elves, dwarves, and half-orcs. I wanted to create a setting for stories that was more inspired by the world around us, and more specifically, the cities we live in, which are teeming stories and adventures around every corner. And since, in my opinion, the only thing that defines something as being “fantasy” is the presence of magic, then I realized there was nothing stopping me from imagining just such a place.

Of course, I have lots of projects in the works: new books, games, a graphic novel, etc., but I have to see where the momentum takes me, and right now I am in a place where I am trying to find that clearly laid-out path. In the meantime, I am just going to make a lot more Gateway-focused artwork.

HM: Why are animal and creature-influenced characters and beings compelling to you as an artist? What opportunities does that give you that realism wouldn’t?

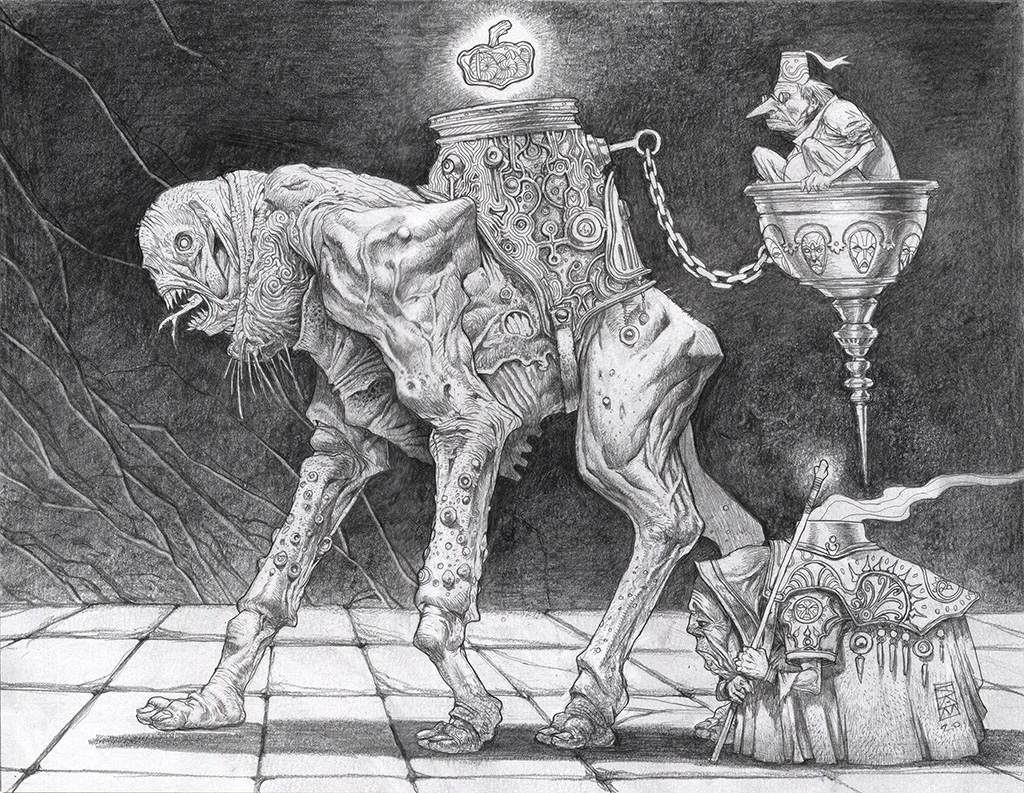

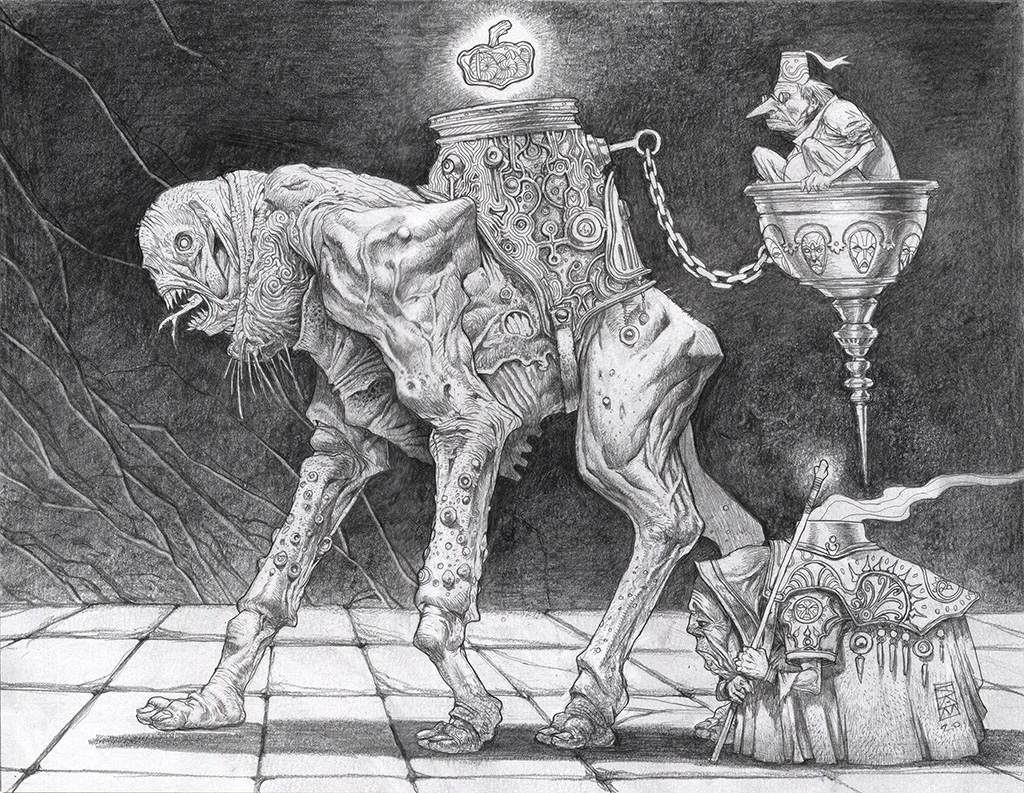

SAM: Using animals as metaphor for characters is an opportunity to strip away any pre-loaded conceptions or biases that an audience may come to the table with. I can explore grandiose notions about my characters that might otherwise push the boundaries of credibility; I can exaggerate with near impunity when it comes to the “big” ideas and have things make sense because of what people know about the animal world.

In Gateway, Fish-folk are more attuned to magic because they come from the sea, a place full of mystery, and therefore the birthplace of magic in the world of Gateway. It’s where I imagine all of the magical ley-line nodes that crisscross the surface of the Known World are located. Whereas Bird-folk are more attuned to the spiritual world, the realm of the gods, who settled in the high peaks of mountains where only birds can reach.

Recently I was watching a documentary about sea-life and it showed this battle between a certain kind of fish in a coral reef and sea-urchins – the urchins seem to just pop up out of nowhere in the fish’s favorite feeding grounds and suck all the nutrients out of the place, so the fish have to try to re-locate them, but the urchins just keep coming back and multiplying faster and faster. This is great story fodder! Imagine one morning you wake up and look out your window only to see an army of silent, giant sea-urchins has invaded your town while you were sleeping and are sucking the life out of all the plants and trees around you!

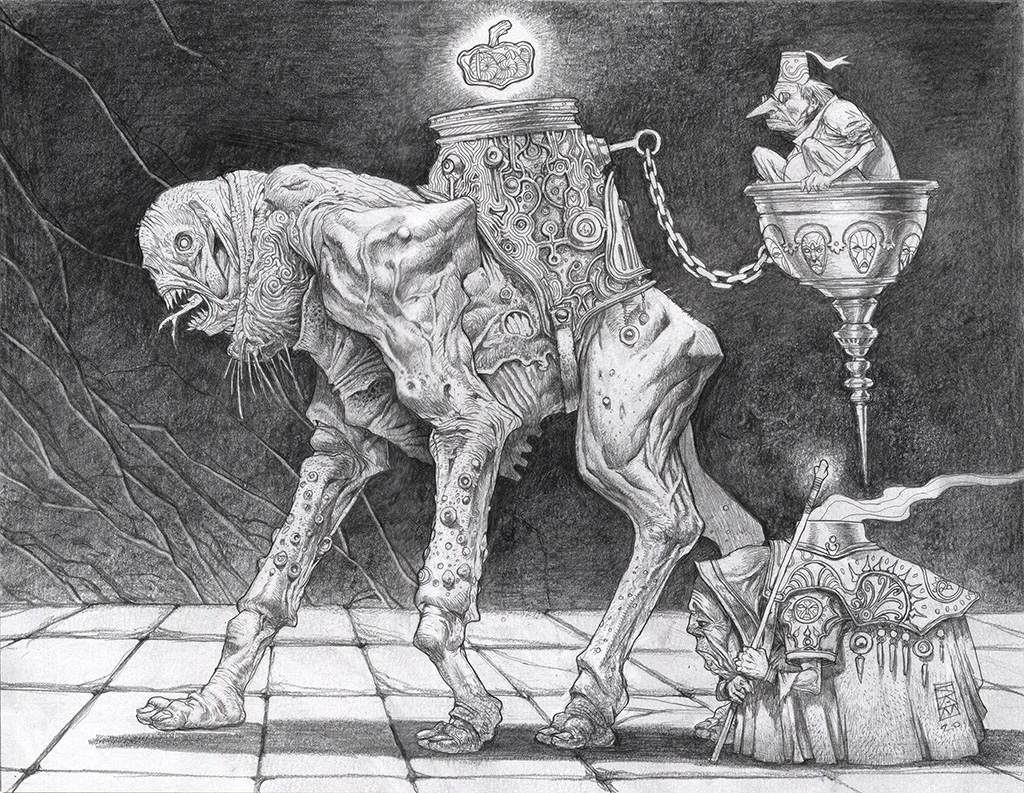

I will say, though, I often like to put human heads onto animalistic bodies to sort of flip the script on the typical approach to anthropomorphism – it’s a fun way to comeup with an unsettling creature design.

HM: What do you think the importance of fantasy storytelling might be right now in comparison to other decades? What keeps you working in this field?

SAM: Well, not to engage in one of those hackneyed “In these difficult times…” kinds of statements, but honestly I think fantasy (or any genre for that matter) as metaphor is one of the most effective ways to communicate ideas to a wider group of people who may otherwise not talk to one another, since open debate and discussion about ideas is increasingly a path fraught with land-mines. Ultimately every form of art making is a way of communicating with other human beings, one that crosses cultural, political, philosophical, and language barriers.

When you learn things like how Dolly Parton’s music is beloved by people of all stripes, in places like Queens, New York, Southern Africa, and aboriginal Australia, all of which are just about as far away from the Smoky Mountains as you can get, then you realize how powerful and deeply felt the ideas one expresses in art can be to so many people. When you find out that fear of angering invisible elves compels the government of Iceland to RE-ROUTE an entire highway to avoid having to move the boulder they live in, that’s when you realize the power of these kinds of concepts. Fantasy, magic, mysticism, mythology are story-telling devices shared by pretty much every culture in every time period around the world, so what could be more relevant and important than that?

Sean's Website

SEAN ANDREW MURRAY Gallery

Interview by Hannah Means-Shannon

One of this issue #299's cover artists, Sean Andrew Murray, has been quietly building a wealth of detail into a world that has the feeling of a “found” location, a discovery of a reality as nuanced as an ancient European capitol at the end of the middle ages. Wandering down its streets only prompts more questions, and meeting each of its denizens opens up new concepts in the relationship between magic and religious perspectives for these beings. “Gateway” is a place and a phenomenon, continuously evolving for Murray, whose other work includes concept art video games, tabletop gaming, music, film, TV, and teaching the crafts of illustration and world-building.

You can encounter “Gateway” through Murray’s crowdfunded books, expansion into tabletop gaming, and now, into 3D sculpture via one of his clients, Sideshow Collectibles. Wander into “Gateway” and you may never find your way out, most likely because you simply don’t want to.

Heavy Metal: Do you feel that you have a certain personal aesthetic in your work, or do you find that idea limiting?

Sean Andrew Murray: I acknowledge that my work comes across as having an aesthetic, but I like to think that it isn’t a result of overly-calculated choice-making, but rather is an extension of my identity as an artist. People often like to comment on my social media feeds about what my work reminds them of, and I used to get a little annoyed at these kinds of comments. But then I began embracing them when I realized that it would be silly for me to deny that I am a product of my influences – to claim to be entirely original is disingenuous at best.

The only time having an aesthetic is limiting is when it doesn’t come from an honest place. Sometimes it’s hard to know when your work is honest or not - perhaps it is a constant struggle - but I find that the more you embrace the ideas that may seem a little scary, risky or weird, the more you begin narrow in on that inner voice, however elusive it might be.

HM: What drives you toward creating texture and softer line-work rather than harder edges?

SAM: Organic shapes are just more compelling to me I suppose – even, or perhaps especially, when it comes to architecture and vehicles, etc. That mix of the functional with the organic has always captured my imagination.That’s why I think gravitate to artists like Moebius, Miyazaki, Ian Miller, Arthur Rackham, Bosch, etc. Don’t get me wrong, I love designing spaceships and futuristic vehicles, it’s just that I rarely design them to be symmetrical or hard-surfaced!

I love and admire the work of Ralph MacQuarrie and Syd Mead – their genius brought an unforgettable vision to modern science-fiction and was part of my formative years as a young consumer of popular culture. But their aesthetic and approach to design isn’t something that I feel I can personally achieve in my own work. So, I look for more organic forms.

Students who are better at character work than they are at environments often ask me how to design interesting architecture and my response is always the same: approach it the SAME way you design an awesome character. Think about shape, personality, and emotion. I like imagining buildings as living things that could, at any moment, just get up and walk off like a huge elephant or giraffe or float off into the clouds like a jellyfish under the water. I also love the idea of organic or ancient unexplainable forces intermingling with architectural forms to create something that is neither entirely deliberate, nor entirely natural.

HM: How important is it to you for a world in an image to feel “lived in”?

SAM: It is the MOST important thing. “Suspension of disbelief” is all about that feeling of familiarity, which can be applied to any project, no matter how alien the setting. This is a drum I am constantly beating with people who ask me for advice on world-building. How many times have we seen a fantasy piece with a castle that looks like it was built yesterday? It’s not credible! But when you see a castle that looks like it was built over a long period of time by multiple generations of inhabitants, and through periods of war, and plague, and regime change, then that’s when it starts to feel like a real place.

I love the convergence of travel and a passion for local history – when I visit new places, I look for unique stories surrounding that place. For example: San Gimignano in Tuscany, Italy was once known as the “Town of Fine Towers” because at one point its residents were trying to out-do one another with who could build the tallest tower in town. Eventually it got so out of hand that the local magistrates had to pass building codes to put an end to it. All places have stories, and it’s those unique stories that help us believe in the illusion.

HM: When working on a commercial project, how different is that creative mindset for you than when you’re working on something like “Gateway”?

SAM: It depends on the project. These days I have been trying to be a bit pickier about the projects I take on, because sometimes it is not obvious when I take a job whether or not it will be something I can really sink my teeth into. I can sometimes convince myself that I might enjoy it, when there is probably a quieter part of my brain that is saying: “Don’t do it!”. Projects that involve a lot of pre-determined assets are usually not my favorite jobs – I get bogged down by the specifics and the process doesn’t flow as well as when I am working on my own self-driven work.

When creating a personal piece, I usually start with only a vague notion of where I want to go – I like to let the process of drawing itself guide the concept. I am muchmore interested in client work that involves designing new things or when theart direction is more notional rather than direct. One of my favorite clients Ihave worked for in the past is Sideshow Collectibles, especially their “Courtof the Dead” property… that really felt like working on my own stuff.

HM: If you’re creating something for a gaming world, is it concept-art with single image ideas, or is there action involved, like storyboarding?

SAM: Usually the former. I am either not a very good storyboard artist, or it’s just not something I enjoy doing on a regular basis, although I have done it for various game and film projects in the past. I prefer drawing new things and exploring new concepts each time I set pencil to paper. Something about re-drawing the same faces or characters over and over again just puts all these mental roadblocks in front of me, so it becomes more of a chore than a joy. Believe me, I would love to love storyboarding, but I guess it’s just not my thing.

HM: Have you ever created for 3D products like statuary? If so, what kind of thinking goes into making that a reality?

SAM: I have! Recently I partnered with two INCREDIBLE sculptors, Sazen Lee and David Zhou, to produce a series of collectibles based on my personal IP brand: “Gateway”. The concept behind it is that we are creating objects that you might actually find in a wizard’s shop in the city of Gateway, we are calling it the “Gateway: Collector” series. The first one is available right now on Sideshow’s website. It’s called “The Lamp of the GreatFish”, and it’s based off a piece I did several years back of a huge fish headsticking out of the top of a temple, combined with street lamps I designed for Gateway that use severed phosphorescent fish heads floating in a bowl of water to create light. One of the pieces we have created that has yet to be release is based on my concept of “The Elusive Birdfish.” This will have a little crank on it that you turn to make the fins, tail and mouth of the bird-fish move – it’s really neat!

HM: You have some very specific ideas about world-building, I think, drawing from your teaching life. Are there any really big “do’s” and“don’ts”?

SAM: Ha ha, yes, I do have lots of ideas about world-building, but I probably don’t have enough room in this article to express them all! There are, however, a few key “mantras” that I try to stick to. One of the most important ones is that you really have to be passionate about learning more about the world around you before you can create worlds that other people will find interesting. There is so much inspiration in science, nature, archeology, engineering, history, etc. There’s such an endless well of inspiration to draw from that you would be foolish not to take advantage of all those free ideas! Get outside of your bubble and explore the world, experience new things, read books about stuff you know nothing about, watch documentaries or listen to interesting podcasts, etc.

Another important thing to keep in mind is that world-building should be an on going anditerative process that evolves over time and reacts to both your involvement and the involvement of your audience. That’s why I advise people to start small – don’t try to design the entire galactic empire all in one go. Start with a single planet, or better yet, start with a small town on that one planet and spend some time there - explore it, get to know it intimately. The work you do there with be the springboard for the rest of the universe. Share it with your audience earlier than you think! It’s extremely helpful to see how people react and respond to your ideas before setting things in stone, so to speak. The momentum of an excited audience that has been bought in to what you are creating can help guide you towards interesting solutions faster than if you agonize about it without the benefit of knowing if anyone is interested in the first place!

HM: Gateway has been your personal world for a long time. What does it mean to you and what remains to be explored for you, as an artist, and for the fans that you bring with you?

SAM: I think of Gateway as a life-long project at this point. I have been with it, or rather it has been with me, for so long now that I don’t think there is a point at which I will say: “I’m done.” When I am drawing for myself, the images tend mostly towards envisioning new characters and corners of Gateway. I started thinking about it as a response to what I felt was a very conservative genre: fantasy. Although I believe this has changed since those early days, I used to feel as if the fantasy genre, which I love, was mostly populated with Tolkien clones, which didn’t make sense to me because Tolkien already made the best version of Middle Earth, so why try to re-make it?

I didn’t think it was fair that science fiction could have bars full of diverse, bizarre creatures from far-flung places, but inns in fantasy worlds always had the same elves, dwarves, and half-orcs. I wanted to create a setting for stories that was more inspired by the world around us, and more specifically, the cities we live in, which are teeming stories and adventures around every corner. And since, in my opinion, the only thing that defines something as being “fantasy” is the presence of magic, then I realized there was nothing stopping me from imagining just such a place.

Of course, I have lots of projects in the works: new books, games, a graphic novel, etc., but I have to see where the momentum takes me, and right now I am in a place where I am trying to find that clearly laid-out path. In the meantime, I am just going to make a lot more Gateway-focused artwork.

HM: Why are animal and creature-influenced characters and beings compelling to you as an artist? What opportunities does that give you that realism wouldn’t?

SAM: Using animals as metaphor for characters is an opportunity to strip away any pre-loaded conceptions or biases that an audience may come to the table with. I can explore grandiose notions about my characters that might otherwise push the boundaries of credibility; I can exaggerate with near impunity when it comes to the “big” ideas and have things make sense because of what people know about the animal world.

In Gateway, Fish-folk are more attuned to magic because they come from the sea, a place full of mystery, and therefore the birthplace of magic in the world of Gateway. It’s where I imagine all of the magical ley-line nodes that crisscross the surface of the Known World are located. Whereas Bird-folk are more attuned to the spiritual world, the realm of the gods, who settled in the high peaks of mountains where only birds can reach.

Recently I was watching a documentary about sea-life and it showed this battle between a certain kind of fish in a coral reef and sea-urchins – the urchins seem to just pop up out of nowhere in the fish’s favorite feeding grounds and suck all the nutrients out of the place, so the fish have to try to re-locate them, but the urchins just keep coming back and multiplying faster and faster. This is great story fodder! Imagine one morning you wake up and look out your window only to see an army of silent, giant sea-urchins has invaded your town while you were sleeping and are sucking the life out of all the plants and trees around you!

I will say, though, I often like to put human heads onto animalistic bodies to sort of flip the script on the typical approach to anthropomorphism – it’s a fun way to comeup with an unsettling creature design.

HM: What do you think the importance of fantasy storytelling might be right now in comparison to other decades? What keeps you working in this field?

SAM: Well, not to engage in one of those hackneyed “In these difficult times…” kinds of statements, but honestly I think fantasy (or any genre for that matter) as metaphor is one of the most effective ways to communicate ideas to a wider group of people who may otherwise not talk to one another, since open debate and discussion about ideas is increasingly a path fraught with land-mines. Ultimately every form of art making is a way of communicating with other human beings, one that crosses cultural, political, philosophical, and language barriers.

When you learn things like how Dolly Parton’s music is beloved by people of all stripes, in places like Queens, New York, Southern Africa, and aboriginal Australia, all of which are just about as far away from the Smoky Mountains as you can get, then you realize how powerful and deeply felt the ideas one expresses in art can be to so many people. When you find out that fear of angering invisible elves compels the government of Iceland to RE-ROUTE an entire highway to avoid having to move the boulder they live in, that’s when you realize the power of these kinds of concepts. Fantasy, magic, mysticism, mythology are story-telling devices shared by pretty much every culture in every time period around the world, so what could be more relevant and important than that?

Sean's Website

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

Interview by Hannah Means-Shannon

One of this issue #299's cover artists, Sean Andrew Murray, has been quietly building a wealth of detail into a world that has the feeling of a “found” location, a discovery of a reality as nuanced as an ancient European capitol at the end of the middle ages. Wandering down its streets only prompts more questions, and meeting each of its denizens opens up new concepts in the relationship between magic and religious perspectives for these beings. “Gateway” is a place and a phenomenon, continuously evolving for Murray, whose other work includes concept art video games, tabletop gaming, music, film, TV, and teaching the crafts of illustration and world-building.

You can encounter “Gateway” through Murray’s crowdfunded books, expansion into tabletop gaming, and now, into 3D sculpture via one of his clients, Sideshow Collectibles. Wander into “Gateway” and you may never find your way out, most likely because you simply don’t want to.

Heavy Metal: Do you feel that you have a certain personal aesthetic in your work, or do you find that idea limiting?

Sean Andrew Murray: I acknowledge that my work comes across as having an aesthetic, but I like to think that it isn’t a result of overly-calculated choice-making, but rather is an extension of my identity as an artist. People often like to comment on my social media feeds about what my work reminds them of, and I used to get a little annoyed at these kinds of comments. But then I began embracing them when I realized that it would be silly for me to deny that I am a product of my influences – to claim to be entirely original is disingenuous at best.

The only time having an aesthetic is limiting is when it doesn’t come from an honest place. Sometimes it’s hard to know when your work is honest or not - perhaps it is a constant struggle - but I find that the more you embrace the ideas that may seem a little scary, risky or weird, the more you begin narrow in on that inner voice, however elusive it might be.

HM: What drives you toward creating texture and softer line-work rather than harder edges?

SAM: Organic shapes are just more compelling to me I suppose – even, or perhaps especially, when it comes to architecture and vehicles, etc. That mix of the functional with the organic has always captured my imagination.That’s why I think gravitate to artists like Moebius, Miyazaki, Ian Miller, Arthur Rackham, Bosch, etc. Don’t get me wrong, I love designing spaceships and futuristic vehicles, it’s just that I rarely design them to be symmetrical or hard-surfaced!

I love and admire the work of Ralph MacQuarrie and Syd Mead – their genius brought an unforgettable vision to modern science-fiction and was part of my formative years as a young consumer of popular culture. But their aesthetic and approach to design isn’t something that I feel I can personally achieve in my own work. So, I look for more organic forms.

Students who are better at character work than they are at environments often ask me how to design interesting architecture and my response is always the same: approach it the SAME way you design an awesome character. Think about shape, personality, and emotion. I like imagining buildings as living things that could, at any moment, just get up and walk off like a huge elephant or giraffe or float off into the clouds like a jellyfish under the water. I also love the idea of organic or ancient unexplainable forces intermingling with architectural forms to create something that is neither entirely deliberate, nor entirely natural.

HM: How important is it to you for a world in an image to feel “lived in”?

SAM: It is the MOST important thing. “Suspension of disbelief” is all about that feeling of familiarity, which can be applied to any project, no matter how alien the setting. This is a drum I am constantly beating with people who ask me for advice on world-building. How many times have we seen a fantasy piece with a castle that looks like it was built yesterday? It’s not credible! But when you see a castle that looks like it was built over a long period of time by multiple generations of inhabitants, and through periods of war, and plague, and regime change, then that’s when it starts to feel like a real place.

I love the convergence of travel and a passion for local history – when I visit new places, I look for unique stories surrounding that place. For example: San Gimignano in Tuscany, Italy was once known as the “Town of Fine Towers” because at one point its residents were trying to out-do one another with who could build the tallest tower in town. Eventually it got so out of hand that the local magistrates had to pass building codes to put an end to it. All places have stories, and it’s those unique stories that help us believe in the illusion.

HM: When working on a commercial project, how different is that creative mindset for you than when you’re working on something like “Gateway”?

SAM: It depends on the project. These days I have been trying to be a bit pickier about the projects I take on, because sometimes it is not obvious when I take a job whether or not it will be something I can really sink my teeth into. I can sometimes convince myself that I might enjoy it, when there is probably a quieter part of my brain that is saying: “Don’t do it!”. Projects that involve a lot of pre-determined assets are usually not my favorite jobs – I get bogged down by the specifics and the process doesn’t flow as well as when I am working on my own self-driven work.

When creating a personal piece, I usually start with only a vague notion of where I want to go – I like to let the process of drawing itself guide the concept. I am muchmore interested in client work that involves designing new things or when theart direction is more notional rather than direct. One of my favorite clients Ihave worked for in the past is Sideshow Collectibles, especially their “Courtof the Dead” property… that really felt like working on my own stuff.

HM: If you’re creating something for a gaming world, is it concept-art with single image ideas, or is there action involved, like storyboarding?

SAM: Usually the former. I am either not a very good storyboard artist, or it’s just not something I enjoy doing on a regular basis, although I have done it for various game and film projects in the past. I prefer drawing new things and exploring new concepts each time I set pencil to paper. Something about re-drawing the same faces or characters over and over again just puts all these mental roadblocks in front of me, so it becomes more of a chore than a joy. Believe me, I would love to love storyboarding, but I guess it’s just not my thing.

HM: Have you ever created for 3D products like statuary? If so, what kind of thinking goes into making that a reality?

SAM: I have! Recently I partnered with two INCREDIBLE sculptors, Sazen Lee and David Zhou, to produce a series of collectibles based on my personal IP brand: “Gateway”. The concept behind it is that we are creating objects that you might actually find in a wizard’s shop in the city of Gateway, we are calling it the “Gateway: Collector” series. The first one is available right now on Sideshow’s website. It’s called “The Lamp of the GreatFish”, and it’s based off a piece I did several years back of a huge fish headsticking out of the top of a temple, combined with street lamps I designed for Gateway that use severed phosphorescent fish heads floating in a bowl of water to create light. One of the pieces we have created that has yet to be release is based on my concept of “The Elusive Birdfish.” This will have a little crank on it that you turn to make the fins, tail and mouth of the bird-fish move – it’s really neat!

HM: You have some very specific ideas about world-building, I think, drawing from your teaching life. Are there any really big “do’s” and“don’ts”?

SAM: Ha ha, yes, I do have lots of ideas about world-building, but I probably don’t have enough room in this article to express them all! There are, however, a few key “mantras” that I try to stick to. One of the most important ones is that you really have to be passionate about learning more about the world around you before you can create worlds that other people will find interesting. There is so much inspiration in science, nature, archeology, engineering, history, etc. There’s such an endless well of inspiration to draw from that you would be foolish not to take advantage of all those free ideas! Get outside of your bubble and explore the world, experience new things, read books about stuff you know nothing about, watch documentaries or listen to interesting podcasts, etc.

Another important thing to keep in mind is that world-building should be an on going anditerative process that evolves over time and reacts to both your involvement and the involvement of your audience. That’s why I advise people to start small – don’t try to design the entire galactic empire all in one go. Start with a single planet, or better yet, start with a small town on that one planet and spend some time there - explore it, get to know it intimately. The work you do there with be the springboard for the rest of the universe. Share it with your audience earlier than you think! It’s extremely helpful to see how people react and respond to your ideas before setting things in stone, so to speak. The momentum of an excited audience that has been bought in to what you are creating can help guide you towards interesting solutions faster than if you agonize about it without the benefit of knowing if anyone is interested in the first place!

HM: Gateway has been your personal world for a long time. What does it mean to you and what remains to be explored for you, as an artist, and for the fans that you bring with you?

SAM: I think of Gateway as a life-long project at this point. I have been with it, or rather it has been with me, for so long now that I don’t think there is a point at which I will say: “I’m done.” When I am drawing for myself, the images tend mostly towards envisioning new characters and corners of Gateway. I started thinking about it as a response to what I felt was a very conservative genre: fantasy. Although I believe this has changed since those early days, I used to feel as if the fantasy genre, which I love, was mostly populated with Tolkien clones, which didn’t make sense to me because Tolkien already made the best version of Middle Earth, so why try to re-make it?

I didn’t think it was fair that science fiction could have bars full of diverse, bizarre creatures from far-flung places, but inns in fantasy worlds always had the same elves, dwarves, and half-orcs. I wanted to create a setting for stories that was more inspired by the world around us, and more specifically, the cities we live in, which are teeming stories and adventures around every corner. And since, in my opinion, the only thing that defines something as being “fantasy” is the presence of magic, then I realized there was nothing stopping me from imagining just such a place.

Of course, I have lots of projects in the works: new books, games, a graphic novel, etc., but I have to see where the momentum takes me, and right now I am in a place where I am trying to find that clearly laid-out path. In the meantime, I am just going to make a lot more Gateway-focused artwork.

HM: Why are animal and creature-influenced characters and beings compelling to you as an artist? What opportunities does that give you that realism wouldn’t?

SAM: Using animals as metaphor for characters is an opportunity to strip away any pre-loaded conceptions or biases that an audience may come to the table with. I can explore grandiose notions about my characters that might otherwise push the boundaries of credibility; I can exaggerate with near impunity when it comes to the “big” ideas and have things make sense because of what people know about the animal world.

In Gateway, Fish-folk are more attuned to magic because they come from the sea, a place full of mystery, and therefore the birthplace of magic in the world of Gateway. It’s where I imagine all of the magical ley-line nodes that crisscross the surface of the Known World are located. Whereas Bird-folk are more attuned to the spiritual world, the realm of the gods, who settled in the high peaks of mountains where only birds can reach.

Recently I was watching a documentary about sea-life and it showed this battle between a certain kind of fish in a coral reef and sea-urchins – the urchins seem to just pop up out of nowhere in the fish’s favorite feeding grounds and suck all the nutrients out of the place, so the fish have to try to re-locate them, but the urchins just keep coming back and multiplying faster and faster. This is great story fodder! Imagine one morning you wake up and look out your window only to see an army of silent, giant sea-urchins has invaded your town while you were sleeping and are sucking the life out of all the plants and trees around you!

I will say, though, I often like to put human heads onto animalistic bodies to sort of flip the script on the typical approach to anthropomorphism – it’s a fun way to comeup with an unsettling creature design.

HM: What do you think the importance of fantasy storytelling might be right now in comparison to other decades? What keeps you working in this field?

SAM: Well, not to engage in one of those hackneyed “In these difficult times…” kinds of statements, but honestly I think fantasy (or any genre for that matter) as metaphor is one of the most effective ways to communicate ideas to a wider group of people who may otherwise not talk to one another, since open debate and discussion about ideas is increasingly a path fraught with land-mines. Ultimately every form of art making is a way of communicating with other human beings, one that crosses cultural, political, philosophical, and language barriers.

When you learn things like how Dolly Parton’s music is beloved by people of all stripes, in places like Queens, New York, Southern Africa, and aboriginal Australia, all of which are just about as far away from the Smoky Mountains as you can get, then you realize how powerful and deeply felt the ideas one expresses in art can be to so many people. When you find out that fear of angering invisible elves compels the government of Iceland to RE-ROUTE an entire highway to avoid having to move the boulder they live in, that’s when you realize the power of these kinds of concepts. Fantasy, magic, mysticism, mythology are story-telling devices shared by pretty much every culture in every time period around the world, so what could be more relevant and important than that?

Sean's Website