MICHAEL WHELAN Gallery

Interview by Hannah Means-Shannon

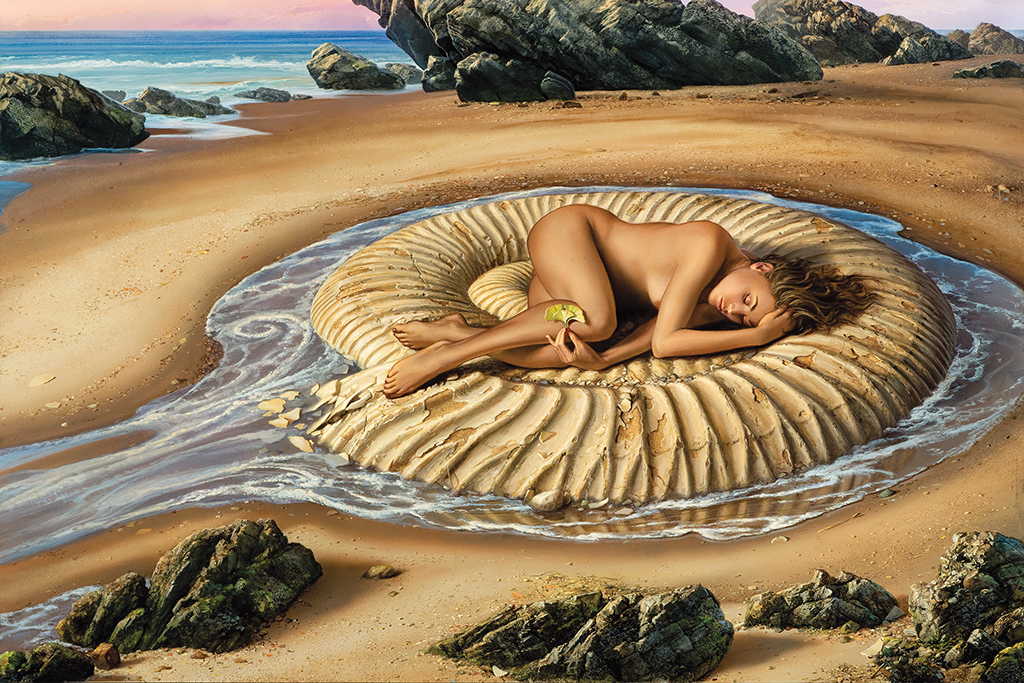

Michael Whelan’s artwork is instantly recognizable, not just for technique or content, but for atmosphere. As a giant in the field of illustration with a staggering slate of awards to his name, Whelan’s own history suggests that there is no one way for life to create an artist, just as there is no one way to illustrate a book cover. All the diverse elements contained in his own life experiences have become grist for the mill in the same way that a complete novel provides a massively varied field of ideas an incidents for illustration. But when you have to choose just one image to represent a created world, in the way that Whelan has to, it becomes a process of selection for reaching the viewer in the most effective way possible. Making those choices and making them stick so astonishingly well is part of Michael Whelan’s personal magic as an artist.

As we discuss below, his goal of lifting viewers out of the routines of daily life through the creation of single images is a constant, daily labor for him, whether on major book projects that could potentially reach millions of readers, or whether in his own personal gallery work that explores universal themes that have enduring impact on Whelan’s own life.

HEAVY METAL: I wanted to start off by asking a very big question. Fans have this idea about your work, and you seem to support that in some of the things that you’ve said about your work: that you are intent on creating a “sense of wonder” in your paintings. How would you define what “wonder” is, and do you think that it comes from different places in the history of art?

Michael Whelan: I’ve never tried to define what “sense of wonder” means. It’s such a ubiquitous term, so wide-ranging, that everyone kind of understands the concept. When you’re talking about art, it could come from amazement that someone could think up something so strange and abnormal in a visionary picture. Or it could come from wonderment at the execution and technique used. I guess through my life there have been images I’ve seen or experiences that I’ve had that cause me to stop in my tracks. And I’ve gotten a sense that I’m in the presence of something special and different… and possibly life-changing. Trying to re-create that is something that I’ve been groping towards with my artwork ever since.

Children experience it all the time. You can just see it on their faces. Because the world is new to them. As we get older and more cynical, we become jaded by ordinary experience. So if you can give someone a new view into a thing they would routinely pass over and not notice, or give them something that they encounter in their ordinary life, but is so removed from their experience of reality that it amazes them, then I think you’ve added something to their lives. And maybe opened up their minds a little bit to the possibilities inherent in our perceived reality.

HM: I remember once hearing a lecture at college about the “sublime” in art, and the main thing I took away from the German Expressionism art they were showing us was that art can be a mental state that an artist is trying to create in the viewer.

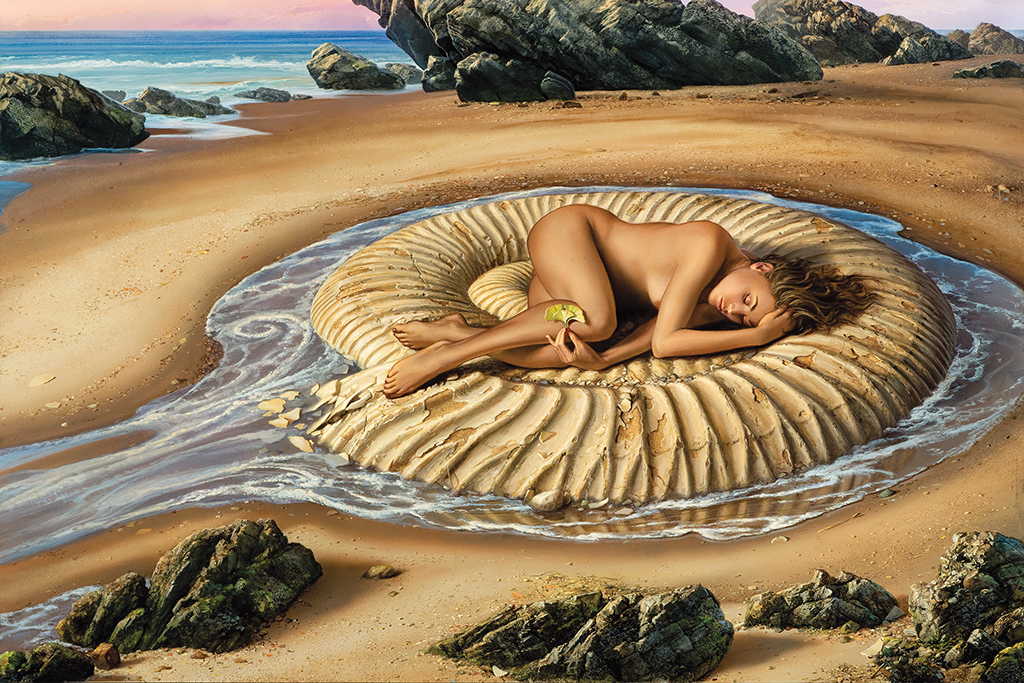

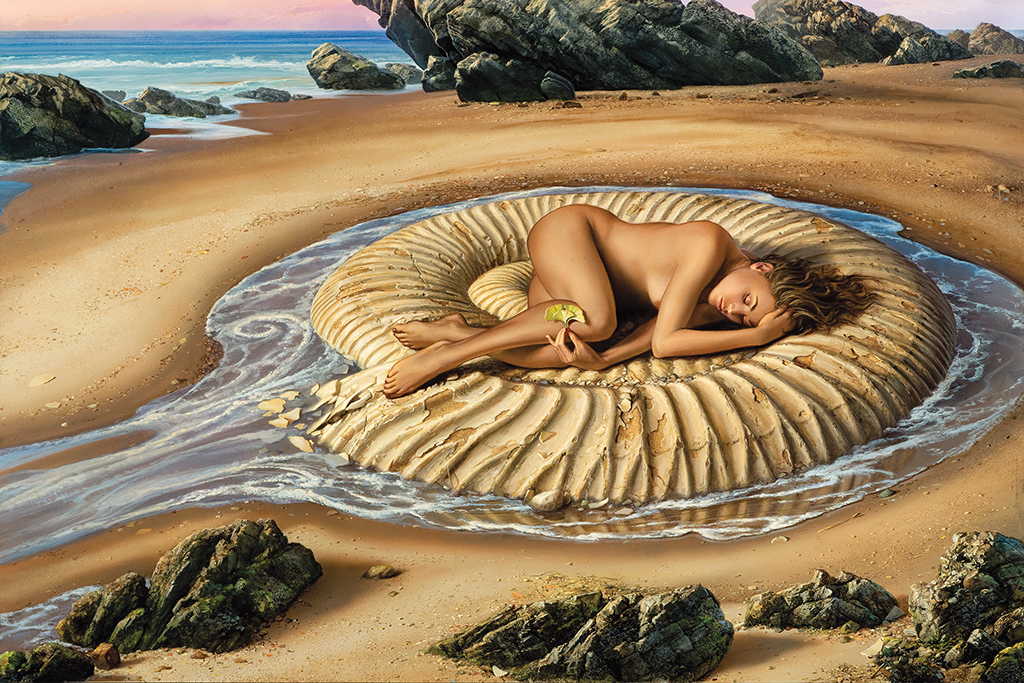

MW: Oh, yes. I’m definitely reaching for that, more in my gallery work than in my illustration. It’s hard to separate the task of illustrating a book from the need to tell a story, or at least suggest that there’s a story involved in your picture. But with my gallery work, it’s not necessarily tied to a written work. I’m free to rely purely on imagery to create an emotion or sensibility. Or to create a set of metaphors that cause the viewer to re-examine the world around them in a different way. I guess the sublime is where you’re transported to when you experience a sense of amazement or wonder. It’s a wonderful feeling and it’s something that, as humans, I think we’ve been seeking since the beginnings of our existence.

It’s one of the duties and part of the calling of being an artist, I think, is to reacquaint people with that experience when they get caught in the humdrum world of everyday experience. It takes an artistic experience sometimes to lift you out of the that and get a new perspective on life.

HM: Is it possible for you, the artist, to have an experience like that when you’re working on something, or is it more that there’s something in your past experience, in your mind, and you’re trying to use that as a point of departure to create for others?

MW: Well, it works both ways. A lot of artists working in our field, or at least some that I’ve talked to, have the same experience as me when working on something: I almost have a sense of disassociation with my hand as if I’m looking over my shoulder, seeing what I’m doing, and thinking, “Where’d that come from?” That’s an amazing and wonderful experience to get a sense that even you, the person creating this thing, don’t know where it’s coming from and why you’re being motivated to create a picture that has certain elements in it that ordinarily you wouldn’t come up with. A lot of it has to do with the phenomenon of pareidolia, like seeing images in clouds. You’re seeing things in the world that others don’t see, and you’re just bringing it into a heightened sense of reality to show it to other people.

Every day when I’m walking around my studio, I see spatters of paint on my pallet, or a shadow falling from an object next to a window, and it looks like something. A lot of times I can’t help but sit down right away and sketch what I just saw or thought I saw. Then, five minutes later I can go look at that shadow, and that suggestion isn’t there anymore. It may suggest something totally different then. But I feel duty bound, when I see it, to record it.

But in a larger sense, just looking at the world, and the changes happening in our culture or environment, can suggest metaphors or images that somehow address what you’re experiencing in a different way. When you have that sensibility, I think it’s important to try to record it, rather than just let it disappear.

HM: That partly explains where some of your ideas come from, since you’re picking up on them just by looking at things…

MW: Oh, yes. I had an experience in my early 30s as if some kind of gate opened up in my head, and I understood that my inspiration needn’t come from what I had been reading in a book or what I’d been seeing in movies, but from the totality of my experience as a human being. From that point on, everything, whether it is a dream, or something I see walking down my driveway and looking at a tree, goes into the well and becomes synthesized and finds expression, one way or another. When that happens, it’s something much more personal than an illustration would be.

But, on the other hand, a lot of my book cover illustrations have a lot to do with things that are going on in my life. I just need to find a point of tangency between the author’s world and my own, and create an image that expresses both at the same time. It’s not easy to do, but when it works, it’s like you’ve found a sweet spot in the illustrator’s call of duty. It allows you to be both expressive of your artistic needs and those of the author and the publisher who wants to get a book sold.

HM: You’re someone who’s known for reading any book you’re going to work on multiple times and really thinking about it, and of course that made a big difference in the development of genre book covers. Is that what you’re doing when you read those books, then, looking for those flashpoints that you can connect to in a work?

MW: Well, I don’t want to burden myself with it the first time that I read a book through. I just want to experience it as a reader and as a fan. Usually, on my first pass through a manuscript, I’ll read it without stopping and forcing myself to take notes. Usually it’s not until my second or third time that I start doubling down and making notes about costuming details, metaphors, or themes that I’m finding which seem important to the author.

At the same time, when you’re putting together the elements for an image, especially one that’s going to be on the cover of a book, you don’t want to give away a spoiler. It’s like a tight-wire act. You’re trying to incorporate as much of that as you can without giving away where the book is going. So when the reader picks up a book, or is reading it, they don’t see the plot twists in the book on the cover. But I do want the reader, when they close the book, to look at the cover, and say, “Oh, yes, that’s what I read. I see why now why this little seal creature is in this mask. It’s because those creatures played an important part in the story.” At the end, when you close the book, I’d like for there to be a little pay off in that respect. I think that makes for a successful and fun book cover.

HM: I can remember doing that a lot as a young person. In that silence right after you finish reading a book, you naturally look at the cover again.

MW: Yes, and so often, we close a book and look at the cover, and say, “What the hell?! Does this have anything to do with what’s in the book?” Which, of course, is why we have that saying, “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” You can’t. They are deliberately misleading. And that can be very annoying. As a reader, and as a fan, I made it my mission in the very beginning of my career, resisting any pressure to do that kind of thing as much as possible.

HM: Well, now that genre book covers are now usually relevant to content, really thanks to you, it seems so bizarre not to have a cover that has something to do with the contents of the book. Why do you think that used to happen so much in publishing previously?

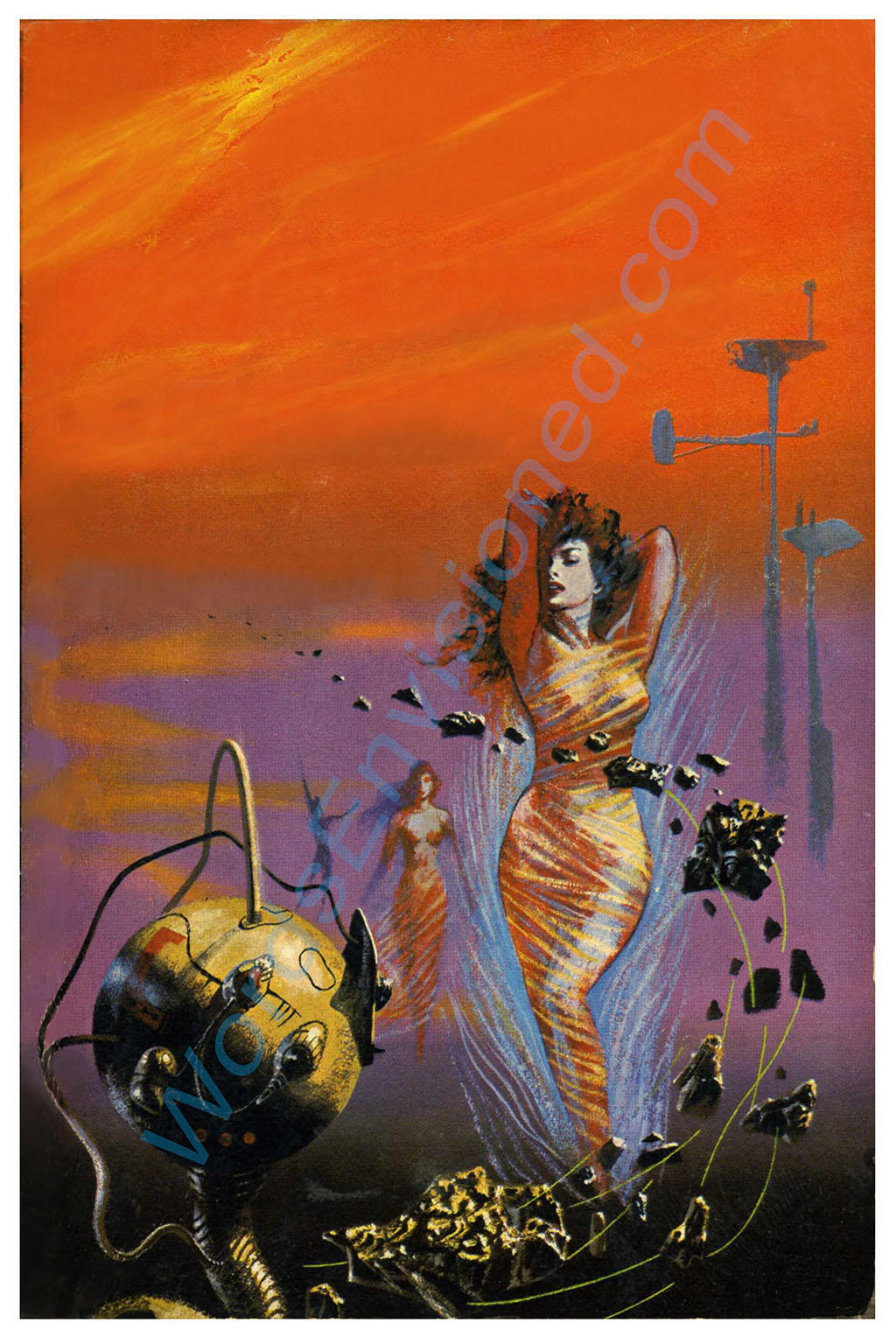

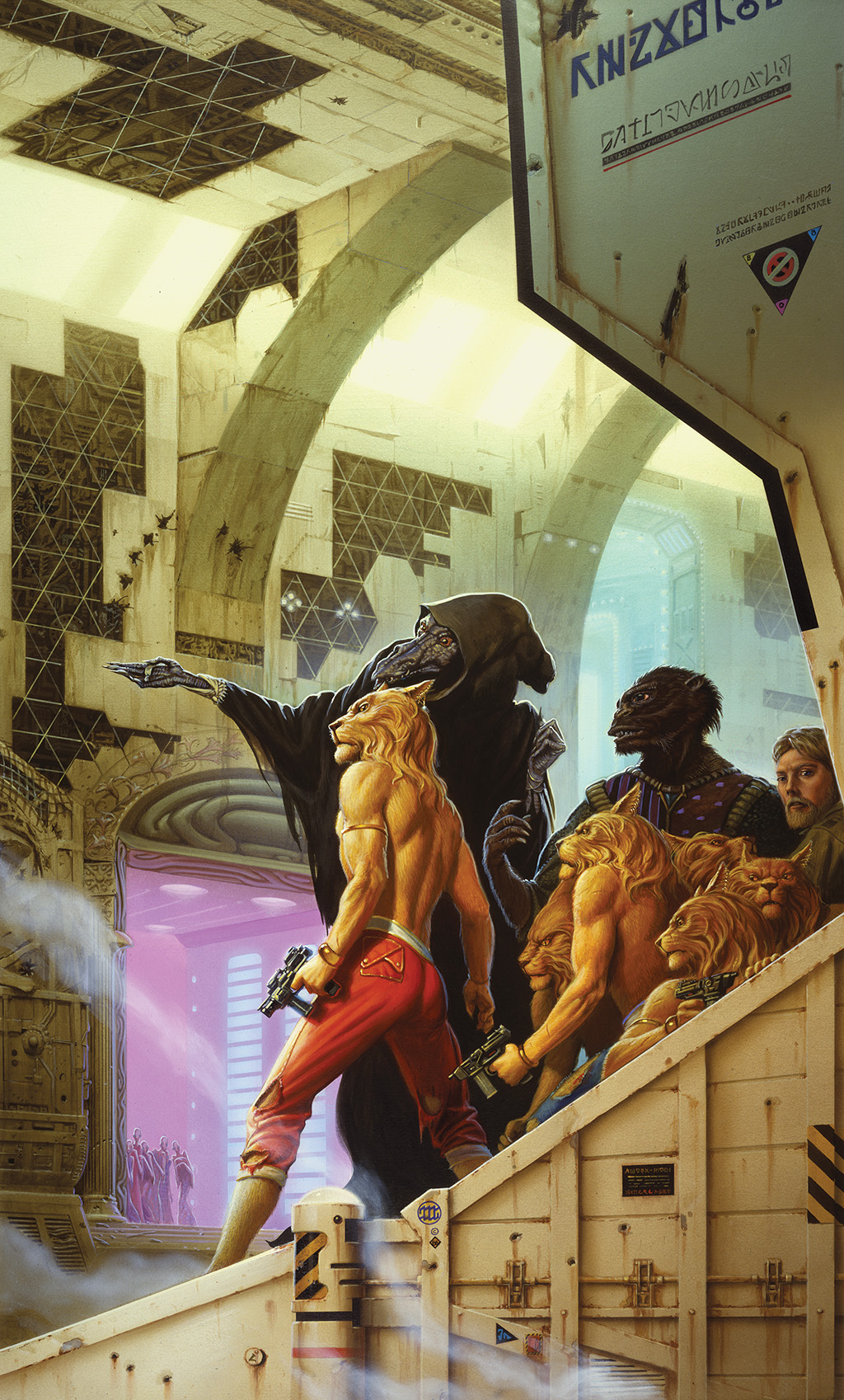

MW: Well, I’ll tell you why. In the early days of science fiction and fantasy paperback publishing, and it’s still true today to a certain extent, they wanted symbols on there which would convey instantly to a reader walking by a stand that this was a science fiction book. To the marketing people, that meant a spaceship, something with fins on it, someone wearing a space suit, aliens, or a galaxy. There was a set of symbols. If it was an adventure story, it had to be a picture of a guy saving a girl from a bug-eyed monster.

Then later, as we got further into the '60s, the genre grew up a little. We got people in publishing who were more sensitive to what science fiction writers were trying to say. They opened up a little bit. They stopped looking down on their audience. They realized that people who were familiar with Isaac Asimov’s books knew what he was about. That they didn’t have to have a typical mediocre cover on a book, but it could be a little more daring.

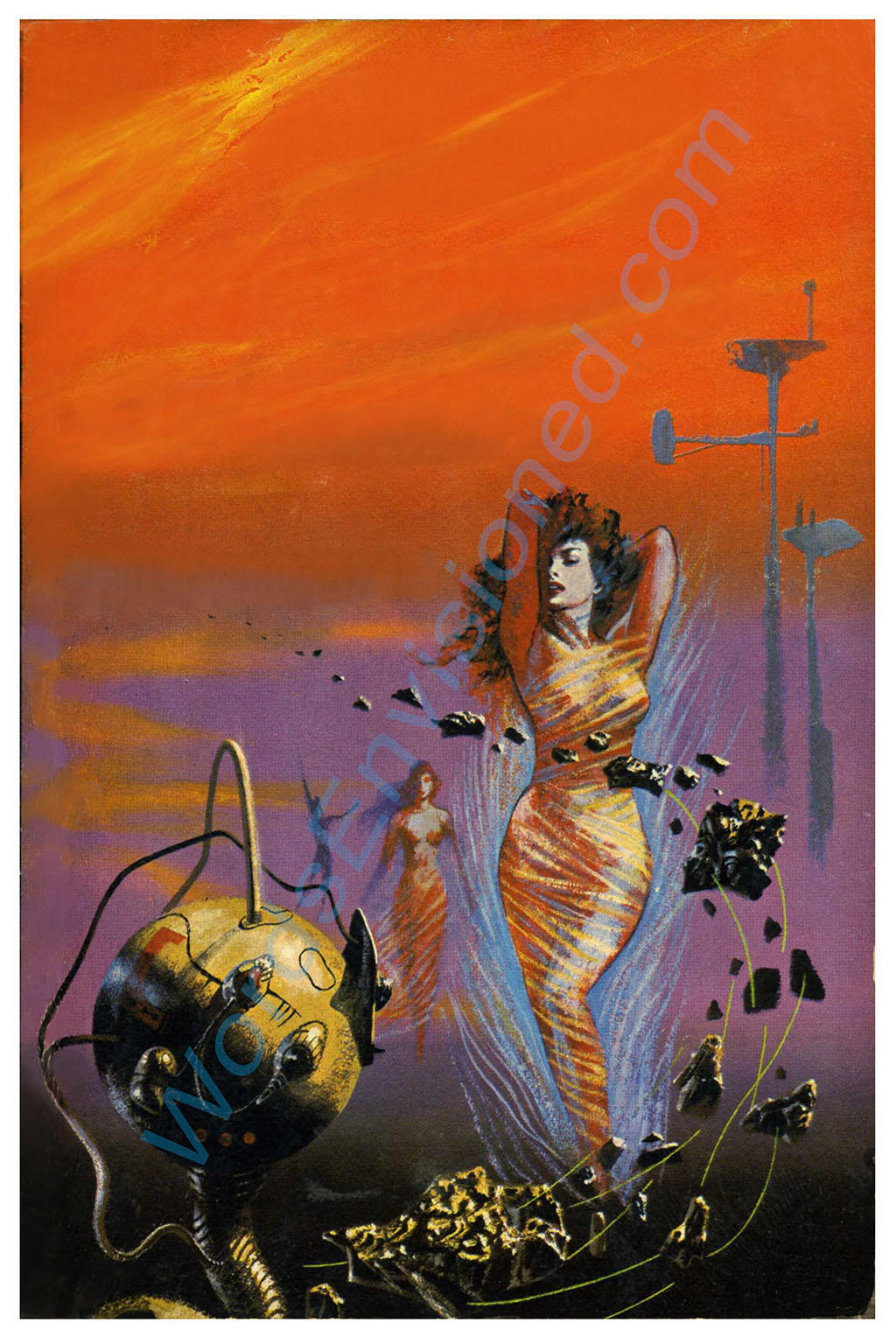

There was a movement in the '60s to get away with that entirely, and just have a smooshy, blobby cover with abstract shapes on it. Maybe there’s be a spaceshippy-type of thing in the background, but it was very surreal. And that conveyed the idea that the book was not based in reality. That was often all that was needed to help the book find its audience. And some of the things that were done back then, by Richard Powers and others, were really cool paintings.

But as a reader myself, I wanted something more closely tied to what I was reading in the book, so my work tended to be more narrative and less symbolic. I’d really like to own a Richard Powers painting even though they weren’t strictly termed illustrations, and didn’t illustrate a theme from the book. They conveyed the feeling of what was in the book, and sometimes that’s enough.

When I’ve created covers for anthologies of horror stories, for examples, I’ve often been given free reign. I didn’t have to do an illustration based on one of the stories of the book, but I could do something that just conveyed the feeling of horror or spookiness for the cover. Both approaches are valid depending on what kind of audience you’re trying to reach.

HM: That must be particularly challenging when it comes to anthologies. I hadn’t even thought about the difficulty there.

MW: Yes, it’s a lot of fun though. The problem is that covers for anthologies don’t pay as well as covers for novels. They always have a lower budget, so I tend to go for other assignments. If I had only one month in a six month period to do a book cover, and there was an anthology and three novels to choose from, I usually choose the novel.

Not always, though. The horror story anthology covers I did on assignment were always my favorite back when I did those. I think I did 10 of them, back in the '70s and '80s. But they stopped publishing those, unfortunately.

HM: So, when you are working on a cover, do you start with several alternatives in your own mind that you then narrow down?

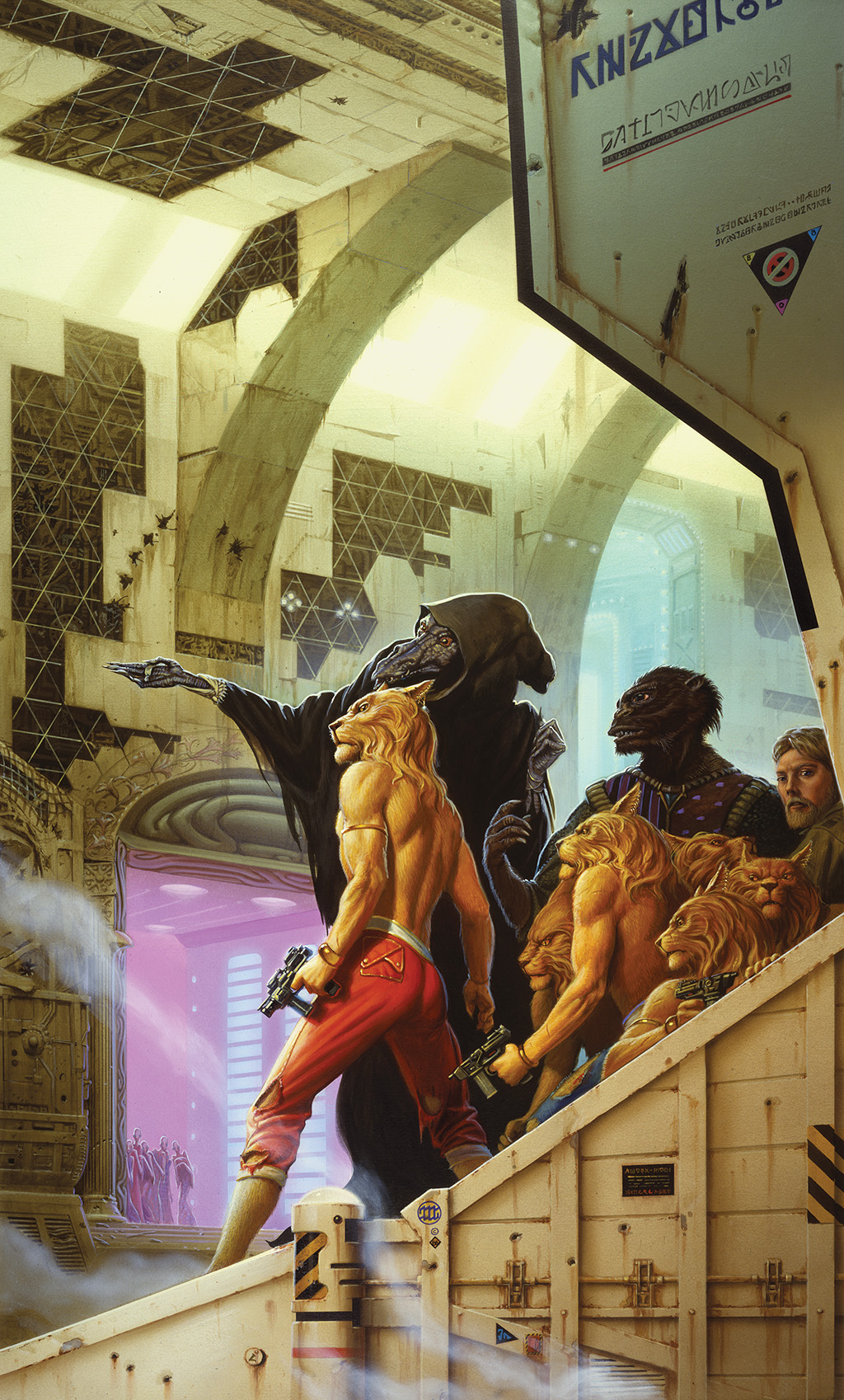

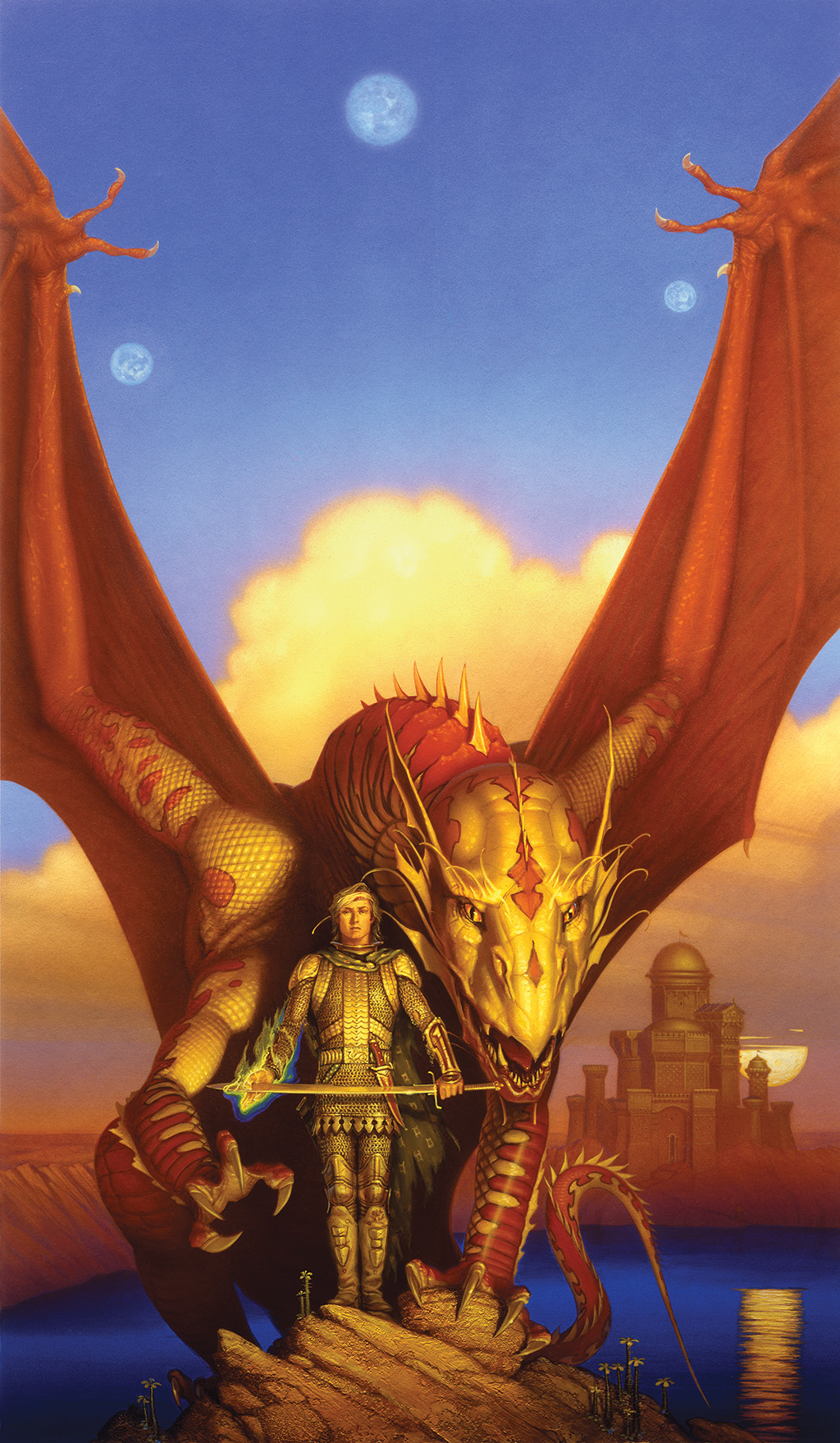

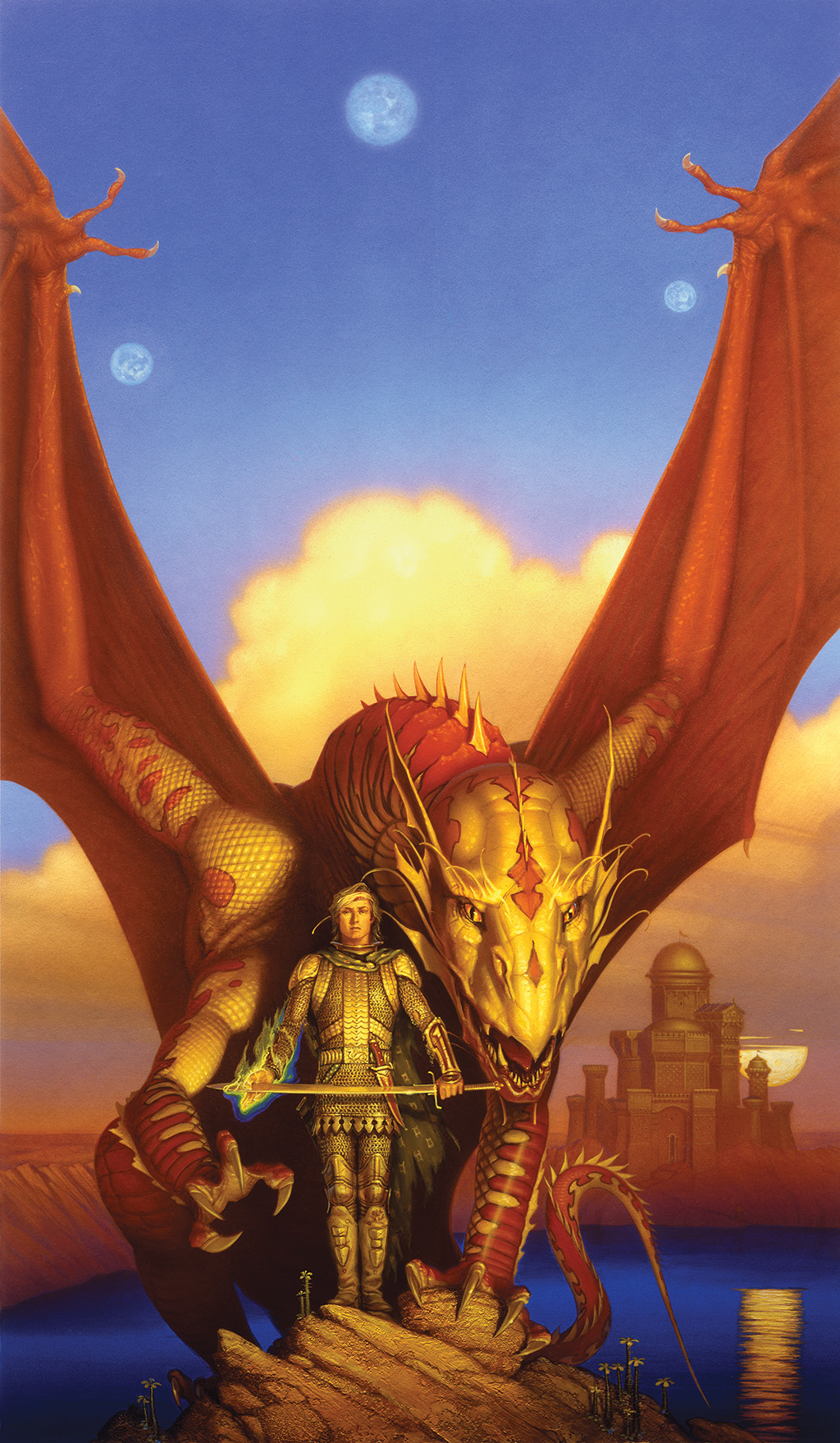

MW: Oh, yes. It depends on the book, of course. Some are more cerebral than others. Fantasy books which are “just” telling an exciting story about heroes and villains, unless there is some kind of metaphorical content in the narrative, it doesn’t really call for a highly symbolic, deep cover approach. My tendency, when I’m reading a book like that, is to see it like a movie in my head. Certain themes will jump out to me as being more fun to do than others. I’ll make note of those on the back of the manuscript pages or whatever. Then I’ll go back to them and decide what are the best representations of what’s in the book.

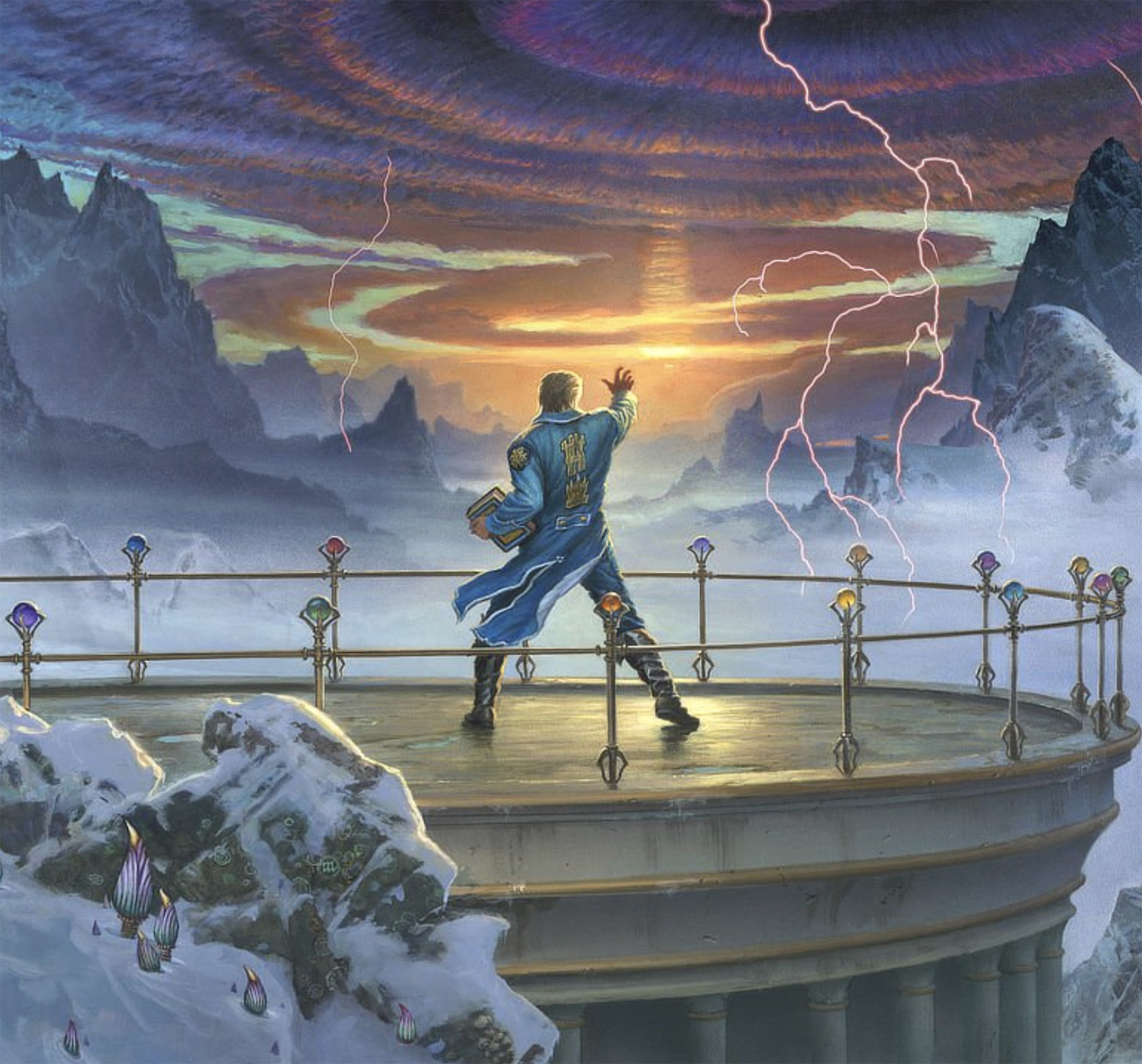

It’s hard when you have an author like Brandon Sanderson, who writes a book that’s 1400 pages long. How do you sum up a sprawling, huge narrative, with scores of characters, into one image? It’s really tough. It takes a lot of thought. Sometimes you can’t take a “one frame from the movie” type of approach to the cover, since you need to find something that sums up the feeling of the book.

Science-fiction books, like books by people like William Gibson, have pretty deep content that address a lot of important issues and reflect on things in our society. There’s a lot of room for metaphorical interpretation of themes along those lines.

I regret that at various points in my career I’ve become type-cast as a certain type of illustrator. If I did a cover for a successful sword and sorcery book, all my job assignments for the next two years would be for that kind of book. That happened several years ago after doing some fantasy covers. So instead of getting offers for science-fiction or horror books, all I got were fantasy commissions. I had to pull away from my career for a while just to press the restart button and come back into it doing a more varied range of work.

I enjoy doing science fiction work because it has probably a greater challenge for the artist because it contains themes that are not easily put into pictures. Unless you’re talking about Ray Bradbury who has deep emotional context, also.

HM: Now, in your own gallery work or other projects you might pursue, do you feel you have total freedom? Or do you feel there are expectations from your gallery fans and following?

MW: Yes. Well, it is a problem. I have so many ideas and when I have been doing a lot of commissioned work and when I find myself with a month open to do a painting just for myself, I have to really wrack my brain to decide what to do. Because there are so many things that I have been wanting to do or want to do that it’s really hard to pick an option and a direction.

It’s not because I have gallery owners say, “We want this kind of painting.”, or “We want that kind of painting”, but I’m well aware of which kind of painting sold the fastest. If a gallery owner says, “If you had done nine more just like this one, I could have sold them all the first day”, it’s hard to remove that from my brain when deciding what to do next. I manage to do it, but it’s not easy. I try to leave a lot of it up to how I’m feeling at that moment, and go with what my gut is telling me at that time.

HM: When you know you’re going to do a show, do you work towards that at all?

MW: Yes, I do. I’ve got to. Because I just can’t keep enough inventory to fill up a show, to put it in a marketing way. I have paintings that I hold onto because my wife won’t let me sell. Either they have my kids as models in them, or they are just favorite paintings of hers, so that limits what I can offer.

I never put illustrations up for sale in a gallery setting. Since I’m fortunate enough that I don’t have to do that. But when I have a gallery show coming up, I have to set aside enough work time to warrant putting on a show. Since usually I only have a few pieces around at any particular kind.

HM: Have you held shows yet where past work has been borrowed from current owners in order to get a clear retrospective of your work over time?

MW: It’s happened a few times, yes. Just because I think there should be at least twelve paintings to show to make it worthwhile for guests to come to a show. I’ve had a gallery that’s representing me in New York for years, but I’m never at a point where I have twelve paintings together that I can show to a potential gallery owner. Until I have an inventory that I can offer as a show, I keep putting it off. People make offers on paintings that I have just finished, and they go. Especially if the buyers are outside of the area, in Hawaii or San Francisco or something, it gets really expensive to ship paintings to shows for a short time.

HM: It’s an interesting problem to have that wouldn’t have occurred to me! In your personal work, you do have cycles of paintings that go together with a little bit of a thematic element. Are there symbols or ideas that you think continue to evolve over time in your personal work?

MW: Yes. Well, they evolve because I’m a person and I’m evolving. My opinions about some things change, though, and then there are things that I have selected to use as symbols in my paintings, and maybe I’ve done five paintings with that symbol, and then I find out another artist somewhere is using a similar symbol. So, I’m forced to put it aside and not use it again, since I don’t want anyone to think that I’m ripping someone else off. That’s happened a few times with me.

But there are a lot of things I want to say, so I just find different symbols. Like I said, I’ve got file drawers full of subjects and scenes. Each one has a different symbol set and different set of ideas, so if I feel road blocked in one thing, I’ll pick something else up that feels right at the time.

I’ve only had one artistic block in my life, and that was in 1988. It led to me doing my first real gallery painting, so it was a good thing that it happened. I kind of smile to myself when people talk about being blocked, since I wish I had a little more of that to give me more free space in my mind to think about other things. But new ideas come to me all the time, and I’m very fortunate in that regard. Unfortunately, I’m a very slow worker, though. Oh well.

HM: It kind of explains why people had studios in the Renaissance and got others to help them get stuff done! Are there symbols you feel you aren’t done with yet, that you’re still fascinated by? Can you share any of those with us?

MW: Oh, sure. Well, there’s a lot of concrete in my paintings because when I was growing up and lived in L.A., I used to play in the Los Angeles River basin. It’s a concrete channel that runs through the city, as you see in the chase scene in Terminator 2. Where I lived, the channels opened out and were at forty-five degree angles from the river bed in certain places. I used to play in those and when I was growing up we also use to have these “duck and cover” drills where all the sirens in the city would go off. We had to duck under our desks in school and cover our faces in the event of an atomic bomb attack! [Laughs] As if that would help.

It’s hilarious to think about in retrospect, but it scared the daylight out of me. It made me and my friends think that the Russians could attack at any time. That they could bomb us today or tomorrow. When I was in the L.A. River basin, and going in some of the tunnels under the streets, I felt safe. I felt loved. I remember being under my desk during one of my classes, and thinking - and I’m in putting this in adult terms, which I wouldn’t have used when I was six years old - “Well, to hell with this! I’m going to run to the river and go in one of the tunnels. I’ll hide there. I’ll be safe from the atomic bombs there, not under a desk!”

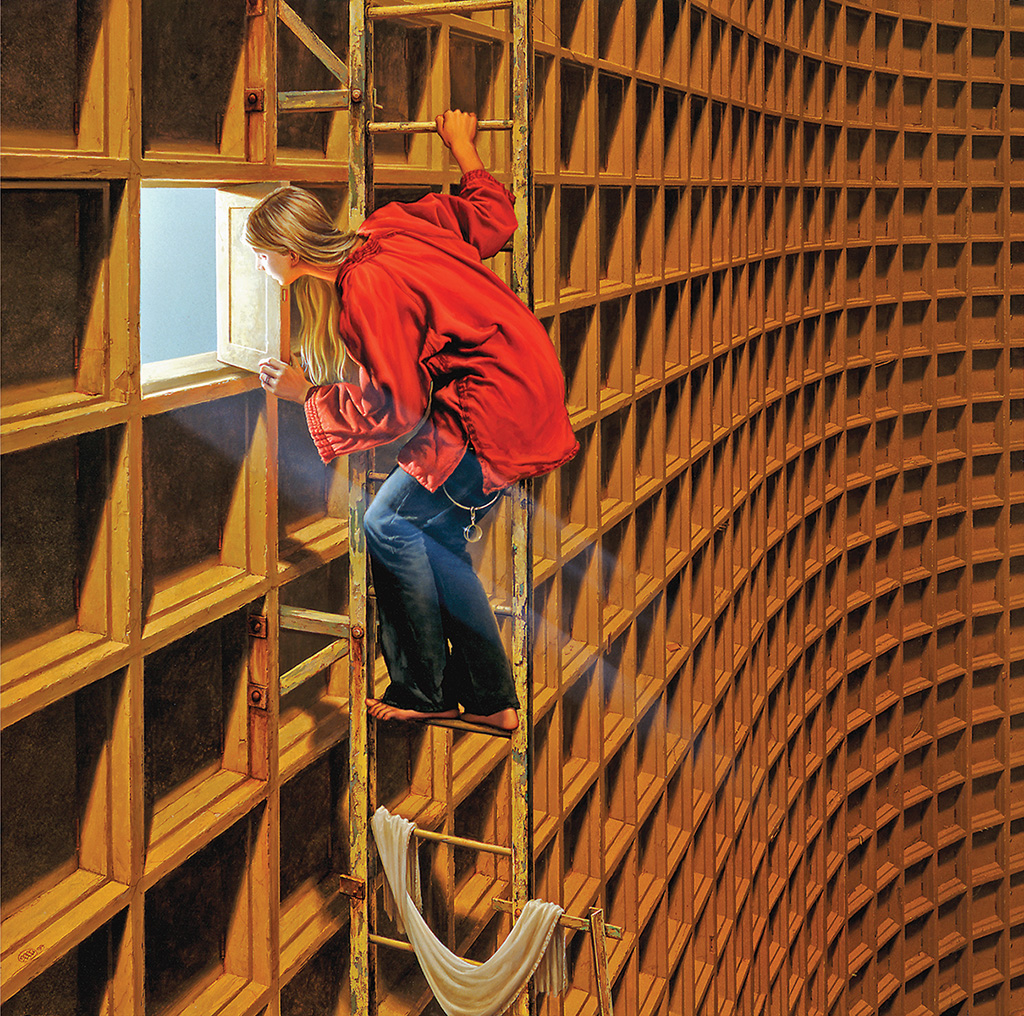

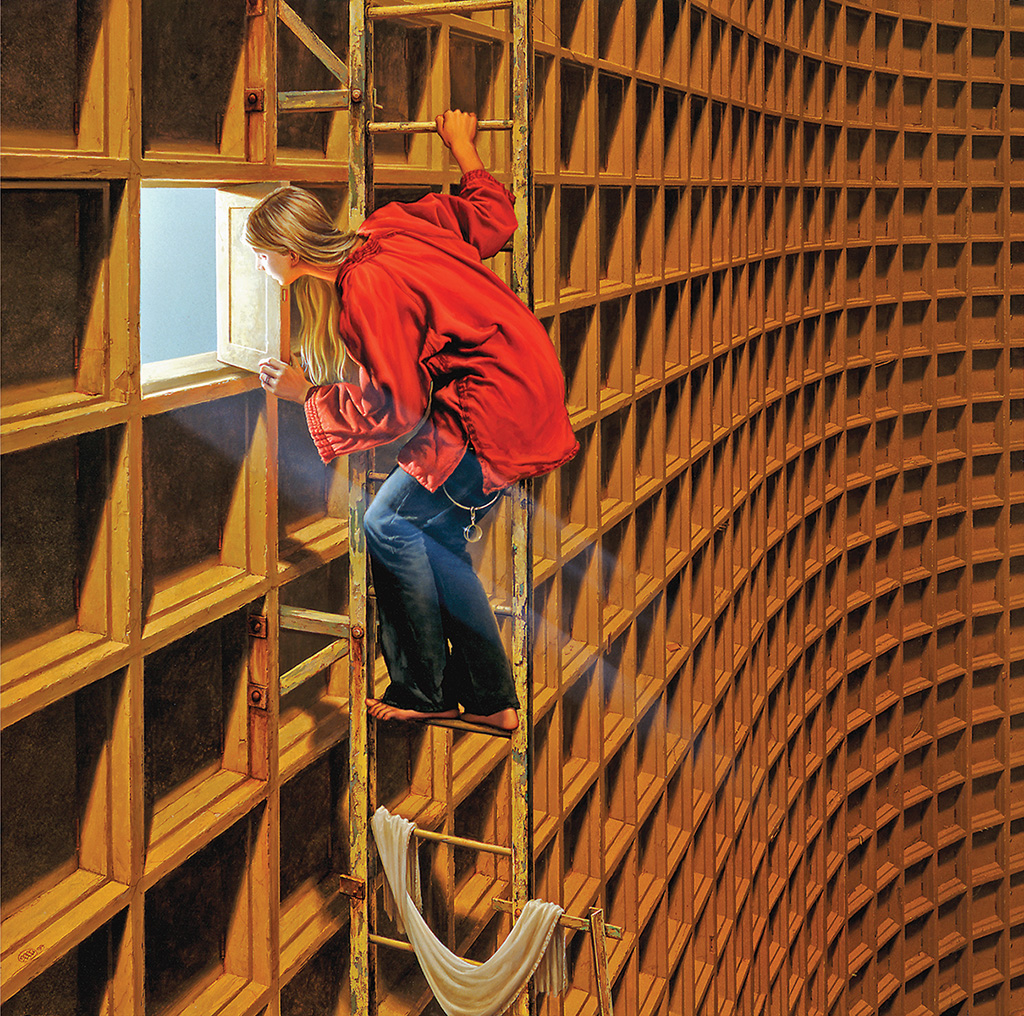

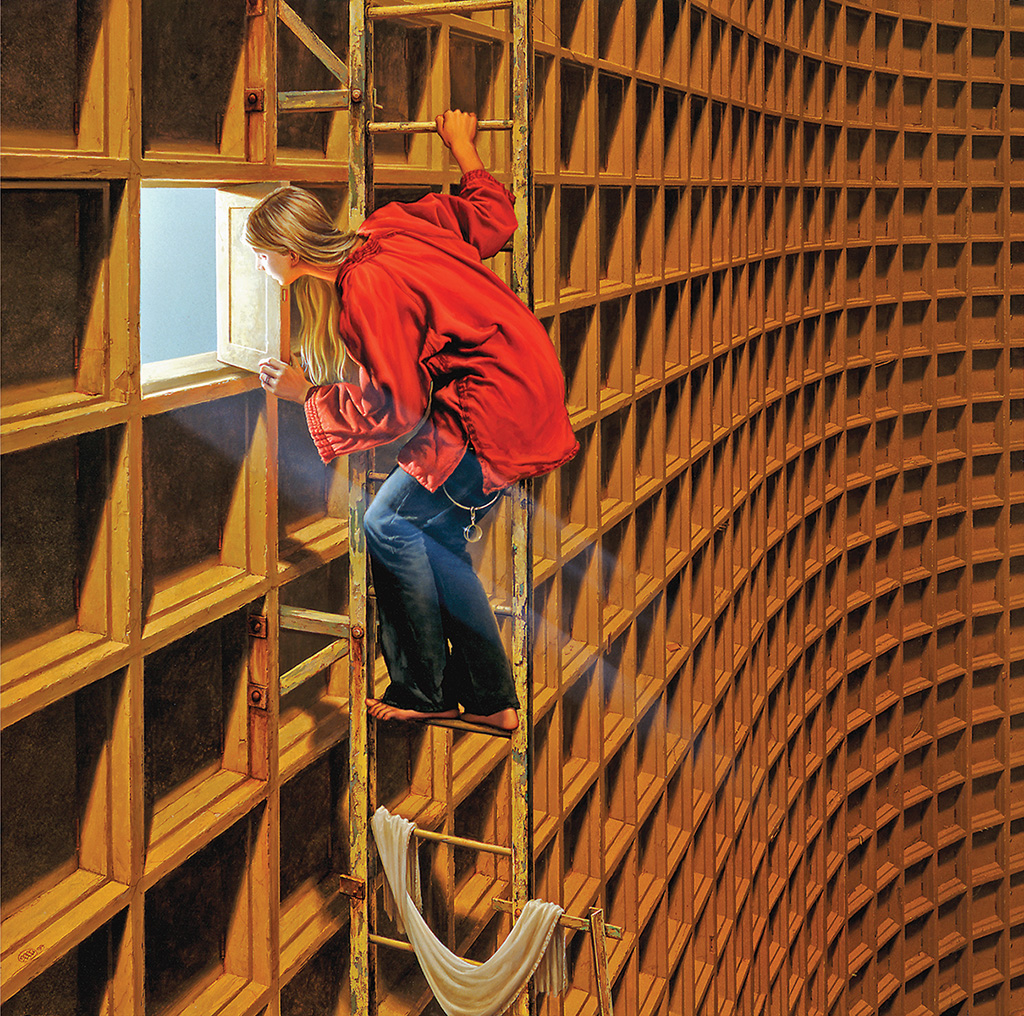

It always represented for me a place of refuge, and a place of fun. Since we always used to ride skateboards and play handball off the sides of the basin. So, concrete for me has a dual meaning when it appears in my paintings. It’s usually connected with having a sense of refuge and safety, like building a wall around yourself, but it’s also the confinement of being in a wall. I think of cities and people being trapped in buildings, working their lives away. Working nine to five jobs. So, it has a dual symbolic meaning for me depending on the context. I’ve done paintings where people are in concrete structures, protected by them, and I’ve done others where they are rising above them and climbing out and away from them, to be free of them.

There’s a symbol that I started using when I was just getting started doing paintings for myself, and that’s a bubble with a little candle flame in the center of it. That’s a symbol of consciousness without body, or of soul, if you want to put it in those terms. It’s the question of whether consciousness can exist without a body, whether anything remains after we die. I’m an agnostic myself, but I find it fascinating, and it’s an idea I ponder regularly.

I’ve done about twelve different paintings employing that as a symbol in different contexts, but usually in situations where there’s lots of breathing room and lots of space. The first time I saw that as an image in my head, I was in an isolation tank during a ninety minute float session. I was there, out in a blue void, and I just saw my consciousness as this fragile bubble with a light in the middle of it. So, it’s been a symbol that I’ve fallen back on multiple times during periods of passage in my life where I felt the need to express that as a metaphor.

HM: That’s awesome. Thank you so much for telling us about that. Have you ever created paintings that provoked controversy?

MW: I have never produced paintings that you could describe as overtly political, that I’ve shown anyway. I have created a painting of Trump, back before the election, in 2016. But it was a joke, and I sent it to Stephen King, and told him that he could throw it in his fireplace if he wanted to, to get a feeling of catharsis. Since he was as upset about where the election was going as I was. So I did that as a Christmas gift for him. But aside from that, I like to focus on more universal things. Things that are cross-cultural. If you read Joseph Campbell, and other works that deal with universal symbolic imagery, there seems to be things common to the human animal all over the world, like there are certain elements that we see in dreams. Giant portals, windows, doors, passages. I try to focus on those as universal symbols. The inspiration for the use of that symbol may be something I’ve read in the paper that morning, but I’ll express it in terms that I feel don’t need to be modified by having a written explanation next to them. I want someone in Thailand or Spain will get as much out of a painting as someone in America or the U.K.

HM: There’s an argument to be made that something is much more powerful when it doesn’t have to use words because, as you say, it can cut across cultures, age groups, vocabulary levels, everything.

MW: The best example of that is music. That’s true of many of the arts, and one of the things that draws me to them.

HM: I agree. I wanted to ask you what you think the continuing value is of fantasy and science fiction in art and in literature. But it sounds like what you’re already hitting on here is that you think we have a psychological need for it.

MW: Yes. I think there’s a certain segment of the population that’s always interested. That wants to see another world. It doesn’t mean you want to escape to it, but sometimes if you step into that world, then look back at the one you’re in, it can inform your perception and allow you to alter your thinking about what you see around you. And then make it a better place. It’s fun, but it could also be seen as somewhat utilitarian in one aspect, in terms of filling a need that’s in a lot of us to experience something beyond what we normally experience in day to day living. And you don’t have to get on a jet or spaceship to go there. You can ride the spaceship of an artist’s imagination to get to this other world and do it from the comfort of your reading room. That sounds like the best of both possible worlds to me.

HM: Well, that’s certainly an argument for the mass market distribution of fiction and art, so that it can get into anyone’s home. It’s so mobile. But also, of course, with the rise of digital, things are even easier. Has the rise of digital affected you at all?

MW: Well, it’s blown my mind! I was one of the judges for the first Spectrum awards, and I was on the advisory board for the first ten years, then I was a judge again. The difference between the first show and the tenth in terms of going digital was phenomenal. By the twentieth show, a huge proportion was digital. And another change from year to year has been how the quality has just been kicked up, and kicked up, and kicked up from one year to the next. I’m floored by the quality and the beauty of a lot of the work that’s being done now.

If I was ten years younger, I’d probably have a lot more digital work under my belt. I use it as a tool, and I use some 3D modeling, but I do a lot of my preliminary sketching now in Photoshop, just because you can set perspective points way out beyond your drawing surface and not have to clear a space in your room to plot out perspective lines, and stuff like that. But I don’t really paint digitally. I’ve done it a couple of times. I won a gold medal at the Society of Illustrators in 1996 for an album cover I did, but that was largely photography-based. There wasn’t a lot of painting to be done. It was mainly a collage of photographic elements. I love it as a tool, and the artists working with it really blow my mind.

Especially in the concept art field, working in movies. The people doing it are so talented. I really feel that we are in a renaissance right now of science fiction and fantasy art. It’s breathtaking to watch it unfold.

MICHAEL WHELAN Gallery

Interview by Hannah Means-Shannon

Michael Whelan’s artwork is instantly recognizable, not just for technique or content, but for atmosphere. As a giant in the field of illustration with a staggering slate of awards to his name, Whelan’s own history suggests that there is no one way for life to create an artist, just as there is no one way to illustrate a book cover. All the diverse elements contained in his own life experiences have become grist for the mill in the same way that a complete novel provides a massively varied field of ideas an incidents for illustration. But when you have to choose just one image to represent a created world, in the way that Whelan has to, it becomes a process of selection for reaching the viewer in the most effective way possible. Making those choices and making them stick so astonishingly well is part of Michael Whelan’s personal magic as an artist.

As we discuss below, his goal of lifting viewers out of the routines of daily life through the creation of single images is a constant, daily labor for him, whether on major book projects that could potentially reach millions of readers, or whether in his own personal gallery work that explores universal themes that have enduring impact on Whelan’s own life.

HEAVY METAL: I wanted to start off by asking a very big question. Fans have this idea about your work, and you seem to support that in some of the things that you’ve said about your work: that you are intent on creating a “sense of wonder” in your paintings. How would you define what “wonder” is, and do you think that it comes from different places in the history of art?

Michael Whelan: I’ve never tried to define what “sense of wonder” means. It’s such a ubiquitous term, so wide-ranging, that everyone kind of understands the concept. When you’re talking about art, it could come from amazement that someone could think up something so strange and abnormal in a visionary picture. Or it could come from wonderment at the execution and technique used. I guess through my life there have been images I’ve seen or experiences that I’ve had that cause me to stop in my tracks. And I’ve gotten a sense that I’m in the presence of something special and different… and possibly life-changing. Trying to re-create that is something that I’ve been groping towards with my artwork ever since.

Children experience it all the time. You can just see it on their faces. Because the world is new to them. As we get older and more cynical, we become jaded by ordinary experience. So if you can give someone a new view into a thing they would routinely pass over and not notice, or give them something that they encounter in their ordinary life, but is so removed from their experience of reality that it amazes them, then I think you’ve added something to their lives. And maybe opened up their minds a little bit to the possibilities inherent in our perceived reality.

HM: I remember once hearing a lecture at college about the “sublime” in art, and the main thing I took away from the German Expressionism art they were showing us was that art can be a mental state that an artist is trying to create in the viewer.

MW: Oh, yes. I’m definitely reaching for that, more in my gallery work than in my illustration. It’s hard to separate the task of illustrating a book from the need to tell a story, or at least suggest that there’s a story involved in your picture. But with my gallery work, it’s not necessarily tied to a written work. I’m free to rely purely on imagery to create an emotion or sensibility. Or to create a set of metaphors that cause the viewer to re-examine the world around them in a different way. I guess the sublime is where you’re transported to when you experience a sense of amazement or wonder. It’s a wonderful feeling and it’s something that, as humans, I think we’ve been seeking since the beginnings of our existence.

It’s one of the duties and part of the calling of being an artist, I think, is to reacquaint people with that experience when they get caught in the humdrum world of everyday experience. It takes an artistic experience sometimes to lift you out of the that and get a new perspective on life.

HM: Is it possible for you, the artist, to have an experience like that when you’re working on something, or is it more that there’s something in your past experience, in your mind, and you’re trying to use that as a point of departure to create for others?

MW: Well, it works both ways. A lot of artists working in our field, or at least some that I’ve talked to, have the same experience as me when working on something: I almost have a sense of disassociation with my hand as if I’m looking over my shoulder, seeing what I’m doing, and thinking, “Where’d that come from?” That’s an amazing and wonderful experience to get a sense that even you, the person creating this thing, don’t know where it’s coming from and why you’re being motivated to create a picture that has certain elements in it that ordinarily you wouldn’t come up with. A lot of it has to do with the phenomenon of pareidolia, like seeing images in clouds. You’re seeing things in the world that others don’t see, and you’re just bringing it into a heightened sense of reality to show it to other people.

Every day when I’m walking around my studio, I see spatters of paint on my pallet, or a shadow falling from an object next to a window, and it looks like something. A lot of times I can’t help but sit down right away and sketch what I just saw or thought I saw. Then, five minutes later I can go look at that shadow, and that suggestion isn’t there anymore. It may suggest something totally different then. But I feel duty bound, when I see it, to record it.

But in a larger sense, just looking at the world, and the changes happening in our culture or environment, can suggest metaphors or images that somehow address what you’re experiencing in a different way. When you have that sensibility, I think it’s important to try to record it, rather than just let it disappear.

HM: That partly explains where some of your ideas come from, since you’re picking up on them just by looking at things…

MW: Oh, yes. I had an experience in my early 30s as if some kind of gate opened up in my head, and I understood that my inspiration needn’t come from what I had been reading in a book or what I’d been seeing in movies, but from the totality of my experience as a human being. From that point on, everything, whether it is a dream, or something I see walking down my driveway and looking at a tree, goes into the well and becomes synthesized and finds expression, one way or another. When that happens, it’s something much more personal than an illustration would be.

But, on the other hand, a lot of my book cover illustrations have a lot to do with things that are going on in my life. I just need to find a point of tangency between the author’s world and my own, and create an image that expresses both at the same time. It’s not easy to do, but when it works, it’s like you’ve found a sweet spot in the illustrator’s call of duty. It allows you to be both expressive of your artistic needs and those of the author and the publisher who wants to get a book sold.

HM: You’re someone who’s known for reading any book you’re going to work on multiple times and really thinking about it, and of course that made a big difference in the development of genre book covers. Is that what you’re doing when you read those books, then, looking for those flashpoints that you can connect to in a work?

MW: Well, I don’t want to burden myself with it the first time that I read a book through. I just want to experience it as a reader and as a fan. Usually, on my first pass through a manuscript, I’ll read it without stopping and forcing myself to take notes. Usually it’s not until my second or third time that I start doubling down and making notes about costuming details, metaphors, or themes that I’m finding which seem important to the author.

At the same time, when you’re putting together the elements for an image, especially one that’s going to be on the cover of a book, you don’t want to give away a spoiler. It’s like a tight-wire act. You’re trying to incorporate as much of that as you can without giving away where the book is going. So when the reader picks up a book, or is reading it, they don’t see the plot twists in the book on the cover. But I do want the reader, when they close the book, to look at the cover, and say, “Oh, yes, that’s what I read. I see why now why this little seal creature is in this mask. It’s because those creatures played an important part in the story.” At the end, when you close the book, I’d like for there to be a little pay off in that respect. I think that makes for a successful and fun book cover.

HM: I can remember doing that a lot as a young person. In that silence right after you finish reading a book, you naturally look at the cover again.

MW: Yes, and so often, we close a book and look at the cover, and say, “What the hell?! Does this have anything to do with what’s in the book?” Which, of course, is why we have that saying, “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” You can’t. They are deliberately misleading. And that can be very annoying. As a reader, and as a fan, I made it my mission in the very beginning of my career, resisting any pressure to do that kind of thing as much as possible.

HM: Well, now that genre book covers are now usually relevant to content, really thanks to you, it seems so bizarre not to have a cover that has something to do with the contents of the book. Why do you think that used to happen so much in publishing previously?

MW: Well, I’ll tell you why. In the early days of science fiction and fantasy paperback publishing, and it’s still true today to a certain extent, they wanted symbols on there which would convey instantly to a reader walking by a stand that this was a science fiction book. To the marketing people, that meant a spaceship, something with fins on it, someone wearing a space suit, aliens, or a galaxy. There was a set of symbols. If it was an adventure story, it had to be a picture of a guy saving a girl from a bug-eyed monster.

Then later, as we got further into the '60s, the genre grew up a little. We got people in publishing who were more sensitive to what science fiction writers were trying to say. They opened up a little bit. They stopped looking down on their audience. They realized that people who were familiar with Isaac Asimov’s books knew what he was about. That they didn’t have to have a typical mediocre cover on a book, but it could be a little more daring.

There was a movement in the '60s to get away with that entirely, and just have a smooshy, blobby cover with abstract shapes on it. Maybe there’s be a spaceshippy-type of thing in the background, but it was very surreal. And that conveyed the idea that the book was not based in reality. That was often all that was needed to help the book find its audience. And some of the things that were done back then, by Richard Powers and others, were really cool paintings.

But as a reader myself, I wanted something more closely tied to what I was reading in the book, so my work tended to be more narrative and less symbolic. I’d really like to own a Richard Powers painting even though they weren’t strictly termed illustrations, and didn’t illustrate a theme from the book. They conveyed the feeling of what was in the book, and sometimes that’s enough.

When I’ve created covers for anthologies of horror stories, for examples, I’ve often been given free reign. I didn’t have to do an illustration based on one of the stories of the book, but I could do something that just conveyed the feeling of horror or spookiness for the cover. Both approaches are valid depending on what kind of audience you’re trying to reach.

HM: That must be particularly challenging when it comes to anthologies. I hadn’t even thought about the difficulty there.

MW: Yes, it’s a lot of fun though. The problem is that covers for anthologies don’t pay as well as covers for novels. They always have a lower budget, so I tend to go for other assignments. If I had only one month in a six month period to do a book cover, and there was an anthology and three novels to choose from, I usually choose the novel.

Not always, though. The horror story anthology covers I did on assignment were always my favorite back when I did those. I think I did 10 of them, back in the '70s and '80s. But they stopped publishing those, unfortunately.

HM: So, when you are working on a cover, do you start with several alternatives in your own mind that you then narrow down?

MW: Oh, yes. It depends on the book, of course. Some are more cerebral than others. Fantasy books which are “just” telling an exciting story about heroes and villains, unless there is some kind of metaphorical content in the narrative, it doesn’t really call for a highly symbolic, deep cover approach. My tendency, when I’m reading a book like that, is to see it like a movie in my head. Certain themes will jump out to me as being more fun to do than others. I’ll make note of those on the back of the manuscript pages or whatever. Then I’ll go back to them and decide what are the best representations of what’s in the book.

It’s hard when you have an author like Brandon Sanderson, who writes a book that’s 1400 pages long. How do you sum up a sprawling, huge narrative, with scores of characters, into one image? It’s really tough. It takes a lot of thought. Sometimes you can’t take a “one frame from the movie” type of approach to the cover, since you need to find something that sums up the feeling of the book.

Science-fiction books, like books by people like William Gibson, have pretty deep content that address a lot of important issues and reflect on things in our society. There’s a lot of room for metaphorical interpretation of themes along those lines.

I regret that at various points in my career I’ve become type-cast as a certain type of illustrator. If I did a cover for a successful sword and sorcery book, all my job assignments for the next two years would be for that kind of book. That happened several years ago after doing some fantasy covers. So instead of getting offers for science-fiction or horror books, all I got were fantasy commissions. I had to pull away from my career for a while just to press the restart button and come back into it doing a more varied range of work.

I enjoy doing science fiction work because it has probably a greater challenge for the artist because it contains themes that are not easily put into pictures. Unless you’re talking about Ray Bradbury who has deep emotional context, also.

HM: Now, in your own gallery work or other projects you might pursue, do you feel you have total freedom? Or do you feel there are expectations from your gallery fans and following?

MW: Yes. Well, it is a problem. I have so many ideas and when I have been doing a lot of commissioned work and when I find myself with a month open to do a painting just for myself, I have to really wrack my brain to decide what to do. Because there are so many things that I have been wanting to do or want to do that it’s really hard to pick an option and a direction.

It’s not because I have gallery owners say, “We want this kind of painting.”, or “We want that kind of painting”, but I’m well aware of which kind of painting sold the fastest. If a gallery owner says, “If you had done nine more just like this one, I could have sold them all the first day”, it’s hard to remove that from my brain when deciding what to do next. I manage to do it, but it’s not easy. I try to leave a lot of it up to how I’m feeling at that moment, and go with what my gut is telling me at that time.

HM: When you know you’re going to do a show, do you work towards that at all?

MW: Yes, I do. I’ve got to. Because I just can’t keep enough inventory to fill up a show, to put it in a marketing way. I have paintings that I hold onto because my wife won’t let me sell. Either they have my kids as models in them, or they are just favorite paintings of hers, so that limits what I can offer.

I never put illustrations up for sale in a gallery setting. Since I’m fortunate enough that I don’t have to do that. But when I have a gallery show coming up, I have to set aside enough work time to warrant putting on a show. Since usually I only have a few pieces around at any particular kind.

HM: Have you held shows yet where past work has been borrowed from current owners in order to get a clear retrospective of your work over time?

MW: It’s happened a few times, yes. Just because I think there should be at least twelve paintings to show to make it worthwhile for guests to come to a show. I’ve had a gallery that’s representing me in New York for years, but I’m never at a point where I have twelve paintings together that I can show to a potential gallery owner. Until I have an inventory that I can offer as a show, I keep putting it off. People make offers on paintings that I have just finished, and they go. Especially if the buyers are outside of the area, in Hawaii or San Francisco or something, it gets really expensive to ship paintings to shows for a short time.

HM: It’s an interesting problem to have that wouldn’t have occurred to me! In your personal work, you do have cycles of paintings that go together with a little bit of a thematic element. Are there symbols or ideas that you think continue to evolve over time in your personal work?

MW: Yes. Well, they evolve because I’m a person and I’m evolving. My opinions about some things change, though, and then there are things that I have selected to use as symbols in my paintings, and maybe I’ve done five paintings with that symbol, and then I find out another artist somewhere is using a similar symbol. So, I’m forced to put it aside and not use it again, since I don’t want anyone to think that I’m ripping someone else off. That’s happened a few times with me.

But there are a lot of things I want to say, so I just find different symbols. Like I said, I’ve got file drawers full of subjects and scenes. Each one has a different symbol set and different set of ideas, so if I feel road blocked in one thing, I’ll pick something else up that feels right at the time.

I’ve only had one artistic block in my life, and that was in 1988. It led to me doing my first real gallery painting, so it was a good thing that it happened. I kind of smile to myself when people talk about being blocked, since I wish I had a little more of that to give me more free space in my mind to think about other things. But new ideas come to me all the time, and I’m very fortunate in that regard. Unfortunately, I’m a very slow worker, though. Oh well.

HM: It kind of explains why people had studios in the Renaissance and got others to help them get stuff done! Are there symbols you feel you aren’t done with yet, that you’re still fascinated by? Can you share any of those with us?

MW: Oh, sure. Well, there’s a lot of concrete in my paintings because when I was growing up and lived in L.A., I used to play in the Los Angeles River basin. It’s a concrete channel that runs through the city, as you see in the chase scene in Terminator 2. Where I lived, the channels opened out and were at forty-five degree angles from the river bed in certain places. I used to play in those and when I was growing up we also use to have these “duck and cover” drills where all the sirens in the city would go off. We had to duck under our desks in school and cover our faces in the event of an atomic bomb attack! [Laughs] As if that would help.

It’s hilarious to think about in retrospect, but it scared the daylight out of me. It made me and my friends think that the Russians could attack at any time. That they could bomb us today or tomorrow. When I was in the L.A. River basin, and going in some of the tunnels under the streets, I felt safe. I felt loved. I remember being under my desk during one of my classes, and thinking - and I’m in putting this in adult terms, which I wouldn’t have used when I was six years old - “Well, to hell with this! I’m going to run to the river and go in one of the tunnels. I’ll hide there. I’ll be safe from the atomic bombs there, not under a desk!”

It always represented for me a place of refuge, and a place of fun. Since we always used to ride skateboards and play handball off the sides of the basin. So, concrete for me has a dual meaning when it appears in my paintings. It’s usually connected with having a sense of refuge and safety, like building a wall around yourself, but it’s also the confinement of being in a wall. I think of cities and people being trapped in buildings, working their lives away. Working nine to five jobs. So, it has a dual symbolic meaning for me depending on the context. I’ve done paintings where people are in concrete structures, protected by them, and I’ve done others where they are rising above them and climbing out and away from them, to be free of them.

There’s a symbol that I started using when I was just getting started doing paintings for myself, and that’s a bubble with a little candle flame in the center of it. That’s a symbol of consciousness without body, or of soul, if you want to put it in those terms. It’s the question of whether consciousness can exist without a body, whether anything remains after we die. I’m an agnostic myself, but I find it fascinating, and it’s an idea I ponder regularly.

I’ve done about twelve different paintings employing that as a symbol in different contexts, but usually in situations where there’s lots of breathing room and lots of space. The first time I saw that as an image in my head, I was in an isolation tank during a ninety minute float session. I was there, out in a blue void, and I just saw my consciousness as this fragile bubble with a light in the middle of it. So, it’s been a symbol that I’ve fallen back on multiple times during periods of passage in my life where I felt the need to express that as a metaphor.

HM: That’s awesome. Thank you so much for telling us about that. Have you ever created paintings that provoked controversy?

MW: I have never produced paintings that you could describe as overtly political, that I’ve shown anyway. I have created a painting of Trump, back before the election, in 2016. But it was a joke, and I sent it to Stephen King, and told him that he could throw it in his fireplace if he wanted to, to get a feeling of catharsis. Since he was as upset about where the election was going as I was. So I did that as a Christmas gift for him. But aside from that, I like to focus on more universal things. Things that are cross-cultural. If you read Joseph Campbell, and other works that deal with universal symbolic imagery, there seems to be things common to the human animal all over the world, like there are certain elements that we see in dreams. Giant portals, windows, doors, passages. I try to focus on those as universal symbols. The inspiration for the use of that symbol may be something I’ve read in the paper that morning, but I’ll express it in terms that I feel don’t need to be modified by having a written explanation next to them. I want someone in Thailand or Spain will get as much out of a painting as someone in America or the U.K.

HM: There’s an argument to be made that something is much more powerful when it doesn’t have to use words because, as you say, it can cut across cultures, age groups, vocabulary levels, everything.

MW: The best example of that is music. That’s true of many of the arts, and one of the things that draws me to them.

HM: I agree. I wanted to ask you what you think the continuing value is of fantasy and science fiction in art and in literature. But it sounds like what you’re already hitting on here is that you think we have a psychological need for it.

MW: Yes. I think there’s a certain segment of the population that’s always interested. That wants to see another world. It doesn’t mean you want to escape to it, but sometimes if you step into that world, then look back at the one you’re in, it can inform your perception and allow you to alter your thinking about what you see around you. And then make it a better place. It’s fun, but it could also be seen as somewhat utilitarian in one aspect, in terms of filling a need that’s in a lot of us to experience something beyond what we normally experience in day to day living. And you don’t have to get on a jet or spaceship to go there. You can ride the spaceship of an artist’s imagination to get to this other world and do it from the comfort of your reading room. That sounds like the best of both possible worlds to me.

HM: Well, that’s certainly an argument for the mass market distribution of fiction and art, so that it can get into anyone’s home. It’s so mobile. But also, of course, with the rise of digital, things are even easier. Has the rise of digital affected you at all?

MW: Well, it’s blown my mind! I was one of the judges for the first Spectrum awards, and I was on the advisory board for the first ten years, then I was a judge again. The difference between the first show and the tenth in terms of going digital was phenomenal. By the twentieth show, a huge proportion was digital. And another change from year to year has been how the quality has just been kicked up, and kicked up, and kicked up from one year to the next. I’m floored by the quality and the beauty of a lot of the work that’s being done now.

If I was ten years younger, I’d probably have a lot more digital work under my belt. I use it as a tool, and I use some 3D modeling, but I do a lot of my preliminary sketching now in Photoshop, just because you can set perspective points way out beyond your drawing surface and not have to clear a space in your room to plot out perspective lines, and stuff like that. But I don’t really paint digitally. I’ve done it a couple of times. I won a gold medal at the Society of Illustrators in 1996 for an album cover I did, but that was largely photography-based. There wasn’t a lot of painting to be done. It was mainly a collage of photographic elements. I love it as a tool, and the artists working with it really blow my mind.

Especially in the concept art field, working in movies. The people doing it are so talented. I really feel that we are in a renaissance right now of science fiction and fantasy art. It’s breathtaking to watch it unfold.

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

Interview by Hannah Means-Shannon

Michael Whelan’s artwork is instantly recognizable, not just for technique or content, but for atmosphere. As a giant in the field of illustration with a staggering slate of awards to his name, Whelan’s own history suggests that there is no one way for life to create an artist, just as there is no one way to illustrate a book cover. All the diverse elements contained in his own life experiences have become grist for the mill in the same way that a complete novel provides a massively varied field of ideas an incidents for illustration. But when you have to choose just one image to represent a created world, in the way that Whelan has to, it becomes a process of selection for reaching the viewer in the most effective way possible. Making those choices and making them stick so astonishingly well is part of Michael Whelan’s personal magic as an artist.

As we discuss below, his goal of lifting viewers out of the routines of daily life through the creation of single images is a constant, daily labor for him, whether on major book projects that could potentially reach millions of readers, or whether in his own personal gallery work that explores universal themes that have enduring impact on Whelan’s own life.

HEAVY METAL: I wanted to start off by asking a very big question. Fans have this idea about your work, and you seem to support that in some of the things that you’ve said about your work: that you are intent on creating a “sense of wonder” in your paintings. How would you define what “wonder” is, and do you think that it comes from different places in the history of art?

Michael Whelan: I’ve never tried to define what “sense of wonder” means. It’s such a ubiquitous term, so wide-ranging, that everyone kind of understands the concept. When you’re talking about art, it could come from amazement that someone could think up something so strange and abnormal in a visionary picture. Or it could come from wonderment at the execution and technique used. I guess through my life there have been images I’ve seen or experiences that I’ve had that cause me to stop in my tracks. And I’ve gotten a sense that I’m in the presence of something special and different… and possibly life-changing. Trying to re-create that is something that I’ve been groping towards with my artwork ever since.

Children experience it all the time. You can just see it on their faces. Because the world is new to them. As we get older and more cynical, we become jaded by ordinary experience. So if you can give someone a new view into a thing they would routinely pass over and not notice, or give them something that they encounter in their ordinary life, but is so removed from their experience of reality that it amazes them, then I think you’ve added something to their lives. And maybe opened up their minds a little bit to the possibilities inherent in our perceived reality.

HM: I remember once hearing a lecture at college about the “sublime” in art, and the main thing I took away from the German Expressionism art they were showing us was that art can be a mental state that an artist is trying to create in the viewer.

MW: Oh, yes. I’m definitely reaching for that, more in my gallery work than in my illustration. It’s hard to separate the task of illustrating a book from the need to tell a story, or at least suggest that there’s a story involved in your picture. But with my gallery work, it’s not necessarily tied to a written work. I’m free to rely purely on imagery to create an emotion or sensibility. Or to create a set of metaphors that cause the viewer to re-examine the world around them in a different way. I guess the sublime is where you’re transported to when you experience a sense of amazement or wonder. It’s a wonderful feeling and it’s something that, as humans, I think we’ve been seeking since the beginnings of our existence.

It’s one of the duties and part of the calling of being an artist, I think, is to reacquaint people with that experience when they get caught in the humdrum world of everyday experience. It takes an artistic experience sometimes to lift you out of the that and get a new perspective on life.

HM: Is it possible for you, the artist, to have an experience like that when you’re working on something, or is it more that there’s something in your past experience, in your mind, and you’re trying to use that as a point of departure to create for others?

MW: Well, it works both ways. A lot of artists working in our field, or at least some that I’ve talked to, have the same experience as me when working on something: I almost have a sense of disassociation with my hand as if I’m looking over my shoulder, seeing what I’m doing, and thinking, “Where’d that come from?” That’s an amazing and wonderful experience to get a sense that even you, the person creating this thing, don’t know where it’s coming from and why you’re being motivated to create a picture that has certain elements in it that ordinarily you wouldn’t come up with. A lot of it has to do with the phenomenon of pareidolia, like seeing images in clouds. You’re seeing things in the world that others don’t see, and you’re just bringing it into a heightened sense of reality to show it to other people.

Every day when I’m walking around my studio, I see spatters of paint on my pallet, or a shadow falling from an object next to a window, and it looks like something. A lot of times I can’t help but sit down right away and sketch what I just saw or thought I saw. Then, five minutes later I can go look at that shadow, and that suggestion isn’t there anymore. It may suggest something totally different then. But I feel duty bound, when I see it, to record it.

But in a larger sense, just looking at the world, and the changes happening in our culture or environment, can suggest metaphors or images that somehow address what you’re experiencing in a different way. When you have that sensibility, I think it’s important to try to record it, rather than just let it disappear.

HM: That partly explains where some of your ideas come from, since you’re picking up on them just by looking at things…

MW: Oh, yes. I had an experience in my early 30s as if some kind of gate opened up in my head, and I understood that my inspiration needn’t come from what I had been reading in a book or what I’d been seeing in movies, but from the totality of my experience as a human being. From that point on, everything, whether it is a dream, or something I see walking down my driveway and looking at a tree, goes into the well and becomes synthesized and finds expression, one way or another. When that happens, it’s something much more personal than an illustration would be.

But, on the other hand, a lot of my book cover illustrations have a lot to do with things that are going on in my life. I just need to find a point of tangency between the author’s world and my own, and create an image that expresses both at the same time. It’s not easy to do, but when it works, it’s like you’ve found a sweet spot in the illustrator’s call of duty. It allows you to be both expressive of your artistic needs and those of the author and the publisher who wants to get a book sold.

HM: You’re someone who’s known for reading any book you’re going to work on multiple times and really thinking about it, and of course that made a big difference in the development of genre book covers. Is that what you’re doing when you read those books, then, looking for those flashpoints that you can connect to in a work?

MW: Well, I don’t want to burden myself with it the first time that I read a book through. I just want to experience it as a reader and as a fan. Usually, on my first pass through a manuscript, I’ll read it without stopping and forcing myself to take notes. Usually it’s not until my second or third time that I start doubling down and making notes about costuming details, metaphors, or themes that I’m finding which seem important to the author.

At the same time, when you’re putting together the elements for an image, especially one that’s going to be on the cover of a book, you don’t want to give away a spoiler. It’s like a tight-wire act. You’re trying to incorporate as much of that as you can without giving away where the book is going. So when the reader picks up a book, or is reading it, they don’t see the plot twists in the book on the cover. But I do want the reader, when they close the book, to look at the cover, and say, “Oh, yes, that’s what I read. I see why now why this little seal creature is in this mask. It’s because those creatures played an important part in the story.” At the end, when you close the book, I’d like for there to be a little pay off in that respect. I think that makes for a successful and fun book cover.

HM: I can remember doing that a lot as a young person. In that silence right after you finish reading a book, you naturally look at the cover again.

MW: Yes, and so often, we close a book and look at the cover, and say, “What the hell?! Does this have anything to do with what’s in the book?” Which, of course, is why we have that saying, “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” You can’t. They are deliberately misleading. And that can be very annoying. As a reader, and as a fan, I made it my mission in the very beginning of my career, resisting any pressure to do that kind of thing as much as possible.

HM: Well, now that genre book covers are now usually relevant to content, really thanks to you, it seems so bizarre not to have a cover that has something to do with the contents of the book. Why do you think that used to happen so much in publishing previously?

MW: Well, I’ll tell you why. In the early days of science fiction and fantasy paperback publishing, and it’s still true today to a certain extent, they wanted symbols on there which would convey instantly to a reader walking by a stand that this was a science fiction book. To the marketing people, that meant a spaceship, something with fins on it, someone wearing a space suit, aliens, or a galaxy. There was a set of symbols. If it was an adventure story, it had to be a picture of a guy saving a girl from a bug-eyed monster.

Then later, as we got further into the '60s, the genre grew up a little. We got people in publishing who were more sensitive to what science fiction writers were trying to say. They opened up a little bit. They stopped looking down on their audience. They realized that people who were familiar with Isaac Asimov’s books knew what he was about. That they didn’t have to have a typical mediocre cover on a book, but it could be a little more daring.

There was a movement in the '60s to get away with that entirely, and just have a smooshy, blobby cover with abstract shapes on it. Maybe there’s be a spaceshippy-type of thing in the background, but it was very surreal. And that conveyed the idea that the book was not based in reality. That was often all that was needed to help the book find its audience. And some of the things that were done back then, by Richard Powers and others, were really cool paintings.

But as a reader myself, I wanted something more closely tied to what I was reading in the book, so my work tended to be more narrative and less symbolic. I’d really like to own a Richard Powers painting even though they weren’t strictly termed illustrations, and didn’t illustrate a theme from the book. They conveyed the feeling of what was in the book, and sometimes that’s enough.

When I’ve created covers for anthologies of horror stories, for examples, I’ve often been given free reign. I didn’t have to do an illustration based on one of the stories of the book, but I could do something that just conveyed the feeling of horror or spookiness for the cover. Both approaches are valid depending on what kind of audience you’re trying to reach.

HM: That must be particularly challenging when it comes to anthologies. I hadn’t even thought about the difficulty there.

MW: Yes, it’s a lot of fun though. The problem is that covers for anthologies don’t pay as well as covers for novels. They always have a lower budget, so I tend to go for other assignments. If I had only one month in a six month period to do a book cover, and there was an anthology and three novels to choose from, I usually choose the novel.

Not always, though. The horror story anthology covers I did on assignment were always my favorite back when I did those. I think I did 10 of them, back in the '70s and '80s. But they stopped publishing those, unfortunately.

HM: So, when you are working on a cover, do you start with several alternatives in your own mind that you then narrow down?

MW: Oh, yes. It depends on the book, of course. Some are more cerebral than others. Fantasy books which are “just” telling an exciting story about heroes and villains, unless there is some kind of metaphorical content in the narrative, it doesn’t really call for a highly symbolic, deep cover approach. My tendency, when I’m reading a book like that, is to see it like a movie in my head. Certain themes will jump out to me as being more fun to do than others. I’ll make note of those on the back of the manuscript pages or whatever. Then I’ll go back to them and decide what are the best representations of what’s in the book.

It’s hard when you have an author like Brandon Sanderson, who writes a book that’s 1400 pages long. How do you sum up a sprawling, huge narrative, with scores of characters, into one image? It’s really tough. It takes a lot of thought. Sometimes you can’t take a “one frame from the movie” type of approach to the cover, since you need to find something that sums up the feeling of the book.

Science-fiction books, like books by people like William Gibson, have pretty deep content that address a lot of important issues and reflect on things in our society. There’s a lot of room for metaphorical interpretation of themes along those lines.

I regret that at various points in my career I’ve become type-cast as a certain type of illustrator. If I did a cover for a successful sword and sorcery book, all my job assignments for the next two years would be for that kind of book. That happened several years ago after doing some fantasy covers. So instead of getting offers for science-fiction or horror books, all I got were fantasy commissions. I had to pull away from my career for a while just to press the restart button and come back into it doing a more varied range of work.

I enjoy doing science fiction work because it has probably a greater challenge for the artist because it contains themes that are not easily put into pictures. Unless you’re talking about Ray Bradbury who has deep emotional context, also.

HM: Now, in your own gallery work or other projects you might pursue, do you feel you have total freedom? Or do you feel there are expectations from your gallery fans and following?

MW: Yes. Well, it is a problem. I have so many ideas and when I have been doing a lot of commissioned work and when I find myself with a month open to do a painting just for myself, I have to really wrack my brain to decide what to do. Because there are so many things that I have been wanting to do or want to do that it’s really hard to pick an option and a direction.

It’s not because I have gallery owners say, “We want this kind of painting.”, or “We want that kind of painting”, but I’m well aware of which kind of painting sold the fastest. If a gallery owner says, “If you had done nine more just like this one, I could have sold them all the first day”, it’s hard to remove that from my brain when deciding what to do next. I manage to do it, but it’s not easy. I try to leave a lot of it up to how I’m feeling at that moment, and go with what my gut is telling me at that time.

HM: When you know you’re going to do a show, do you work towards that at all?

MW: Yes, I do. I’ve got to. Because I just can’t keep enough inventory to fill up a show, to put it in a marketing way. I have paintings that I hold onto because my wife won’t let me sell. Either they have my kids as models in them, or they are just favorite paintings of hers, so that limits what I can offer.

I never put illustrations up for sale in a gallery setting. Since I’m fortunate enough that I don’t have to do that. But when I have a gallery show coming up, I have to set aside enough work time to warrant putting on a show. Since usually I only have a few pieces around at any particular kind.

HM: Have you held shows yet where past work has been borrowed from current owners in order to get a clear retrospective of your work over time?

MW: It’s happened a few times, yes. Just because I think there should be at least twelve paintings to show to make it worthwhile for guests to come to a show. I’ve had a gallery that’s representing me in New York for years, but I’m never at a point where I have twelve paintings together that I can show to a potential gallery owner. Until I have an inventory that I can offer as a show, I keep putting it off. People make offers on paintings that I have just finished, and they go. Especially if the buyers are outside of the area, in Hawaii or San Francisco or something, it gets really expensive to ship paintings to shows for a short time.

HM: It’s an interesting problem to have that wouldn’t have occurred to me! In your personal work, you do have cycles of paintings that go together with a little bit of a thematic element. Are there symbols or ideas that you think continue to evolve over time in your personal work?

MW: Yes. Well, they evolve because I’m a person and I’m evolving. My opinions about some things change, though, and then there are things that I have selected to use as symbols in my paintings, and maybe I’ve done five paintings with that symbol, and then I find out another artist somewhere is using a similar symbol. So, I’m forced to put it aside and not use it again, since I don’t want anyone to think that I’m ripping someone else off. That’s happened a few times with me.

But there are a lot of things I want to say, so I just find different symbols. Like I said, I’ve got file drawers full of subjects and scenes. Each one has a different symbol set and different set of ideas, so if I feel road blocked in one thing, I’ll pick something else up that feels right at the time.

I’ve only had one artistic block in my life, and that was in 1988. It led to me doing my first real gallery painting, so it was a good thing that it happened. I kind of smile to myself when people talk about being blocked, since I wish I had a little more of that to give me more free space in my mind to think about other things. But new ideas come to me all the time, and I’m very fortunate in that regard. Unfortunately, I’m a very slow worker, though. Oh well.

HM: It kind of explains why people had studios in the Renaissance and got others to help them get stuff done! Are there symbols you feel you aren’t done with yet, that you’re still fascinated by? Can you share any of those with us?

MW: Oh, sure. Well, there’s a lot of concrete in my paintings because when I was growing up and lived in L.A., I used to play in the Los Angeles River basin. It’s a concrete channel that runs through the city, as you see in the chase scene in Terminator 2. Where I lived, the channels opened out and were at forty-five degree angles from the river bed in certain places. I used to play in those and when I was growing up we also use to have these “duck and cover” drills where all the sirens in the city would go off. We had to duck under our desks in school and cover our faces in the event of an atomic bomb attack! [Laughs] As if that would help.

It’s hilarious to think about in retrospect, but it scared the daylight out of me. It made me and my friends think that the Russians could attack at any time. That they could bomb us today or tomorrow. When I was in the L.A. River basin, and going in some of the tunnels under the streets, I felt safe. I felt loved. I remember being under my desk during one of my classes, and thinking - and I’m in putting this in adult terms, which I wouldn’t have used when I was six years old - “Well, to hell with this! I’m going to run to the river and go in one of the tunnels. I’ll hide there. I’ll be safe from the atomic bombs there, not under a desk!”

It always represented for me a place of refuge, and a place of fun. Since we always used to ride skateboards and play handball off the sides of the basin. So, concrete for me has a dual meaning when it appears in my paintings. It’s usually connected with having a sense of refuge and safety, like building a wall around yourself, but it’s also the confinement of being in a wall. I think of cities and people being trapped in buildings, working their lives away. Working nine to five jobs. So, it has a dual symbolic meaning for me depending on the context. I’ve done paintings where people are in concrete structures, protected by them, and I’ve done others where they are rising above them and climbing out and away from them, to be free of them.

There’s a symbol that I started using when I was just getting started doing paintings for myself, and that’s a bubble with a little candle flame in the center of it. That’s a symbol of consciousness without body, or of soul, if you want to put it in those terms. It’s the question of whether consciousness can exist without a body, whether anything remains after we die. I’m an agnostic myself, but I find it fascinating, and it’s an idea I ponder regularly.

I’ve done about twelve different paintings employing that as a symbol in different contexts, but usually in situations where there’s lots of breathing room and lots of space. The first time I saw that as an image in my head, I was in an isolation tank during a ninety minute float session. I was there, out in a blue void, and I just saw my consciousness as this fragile bubble with a light in the middle of it. So, it’s been a symbol that I’ve fallen back on multiple times during periods of passage in my life where I felt the need to express that as a metaphor.

HM: That’s awesome. Thank you so much for telling us about that. Have you ever created paintings that provoked controversy?

MW: I have never produced paintings that you could describe as overtly political, that I’ve shown anyway. I have created a painting of Trump, back before the election, in 2016. But it was a joke, and I sent it to Stephen King, and told him that he could throw it in his fireplace if he wanted to, to get a feeling of catharsis. Since he was as upset about where the election was going as I was. So I did that as a Christmas gift for him. But aside from that, I like to focus on more universal things. Things that are cross-cultural. If you read Joseph Campbell, and other works that deal with universal symbolic imagery, there seems to be things common to the human animal all over the world, like there are certain elements that we see in dreams. Giant portals, windows, doors, passages. I try to focus on those as universal symbols. The inspiration for the use of that symbol may be something I’ve read in the paper that morning, but I’ll express it in terms that I feel don’t need to be modified by having a written explanation next to them. I want someone in Thailand or Spain will get as much out of a painting as someone in America or the U.K.

HM: There’s an argument to be made that something is much more powerful when it doesn’t have to use words because, as you say, it can cut across cultures, age groups, vocabulary levels, everything.

MW: The best example of that is music. That’s true of many of the arts, and one of the things that draws me to them.

HM: I agree. I wanted to ask you what you think the continuing value is of fantasy and science fiction in art and in literature. But it sounds like what you’re already hitting on here is that you think we have a psychological need for it.

MW: Yes. I think there’s a certain segment of the population that’s always interested. That wants to see another world. It doesn’t mean you want to escape to it, but sometimes if you step into that world, then look back at the one you’re in, it can inform your perception and allow you to alter your thinking about what you see around you. And then make it a better place. It’s fun, but it could also be seen as somewhat utilitarian in one aspect, in terms of filling a need that’s in a lot of us to experience something beyond what we normally experience in day to day living. And you don’t have to get on a jet or spaceship to go there. You can ride the spaceship of an artist’s imagination to get to this other world and do it from the comfort of your reading room. That sounds like the best of both possible worlds to me.

HM: Well, that’s certainly an argument for the mass market distribution of fiction and art, so that it can get into anyone’s home. It’s so mobile. But also, of course, with the rise of digital, things are even easier. Has the rise of digital affected you at all?

MW: Well, it’s blown my mind! I was one of the judges for the first Spectrum awards, and I was on the advisory board for the first ten years, then I was a judge again. The difference between the first show and the tenth in terms of going digital was phenomenal. By the twentieth show, a huge proportion was digital. And another change from year to year has been how the quality has just been kicked up, and kicked up, and kicked up from one year to the next. I’m floored by the quality and the beauty of a lot of the work that’s being done now.