CHRIS HUANTE Interview

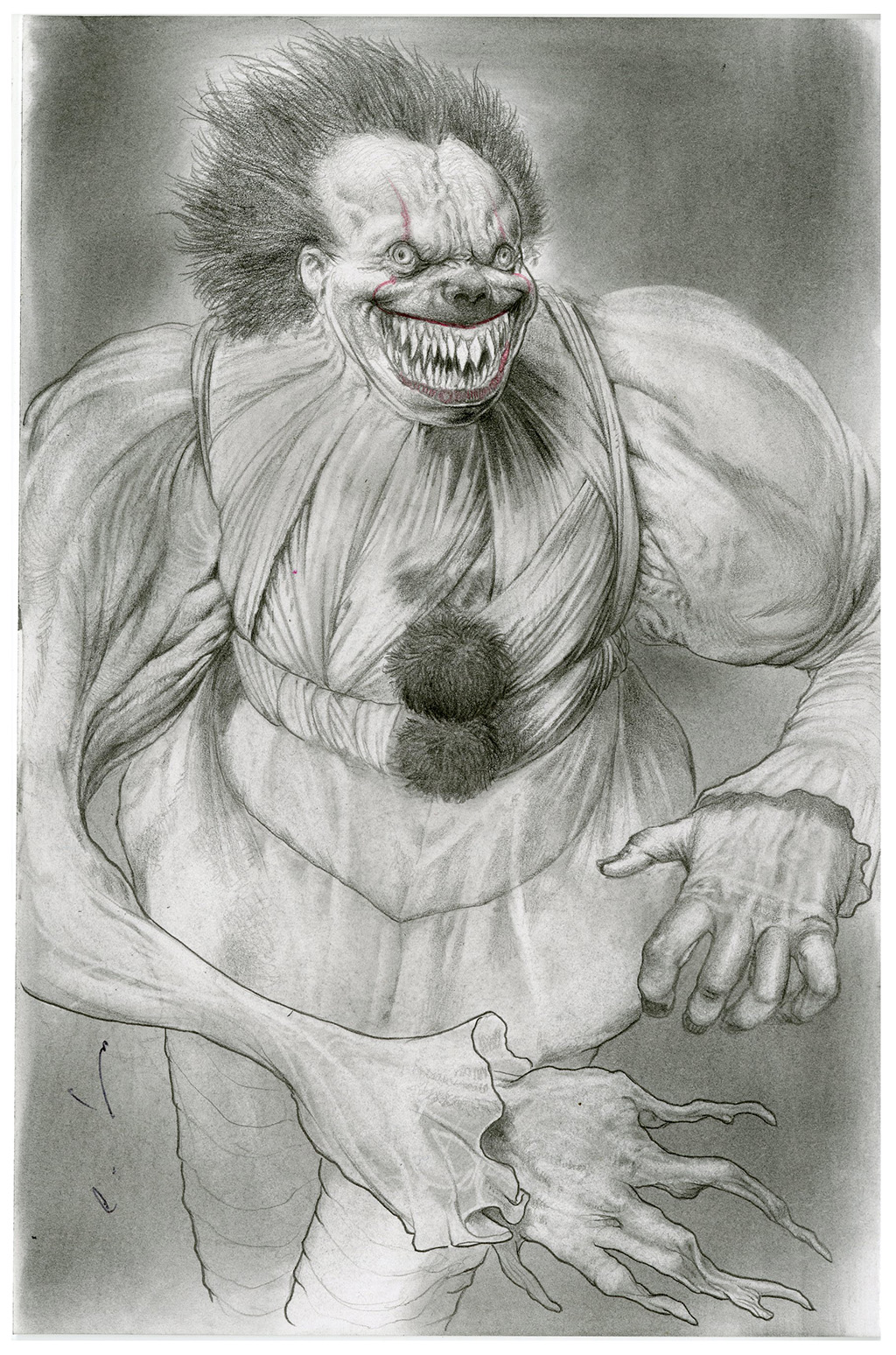

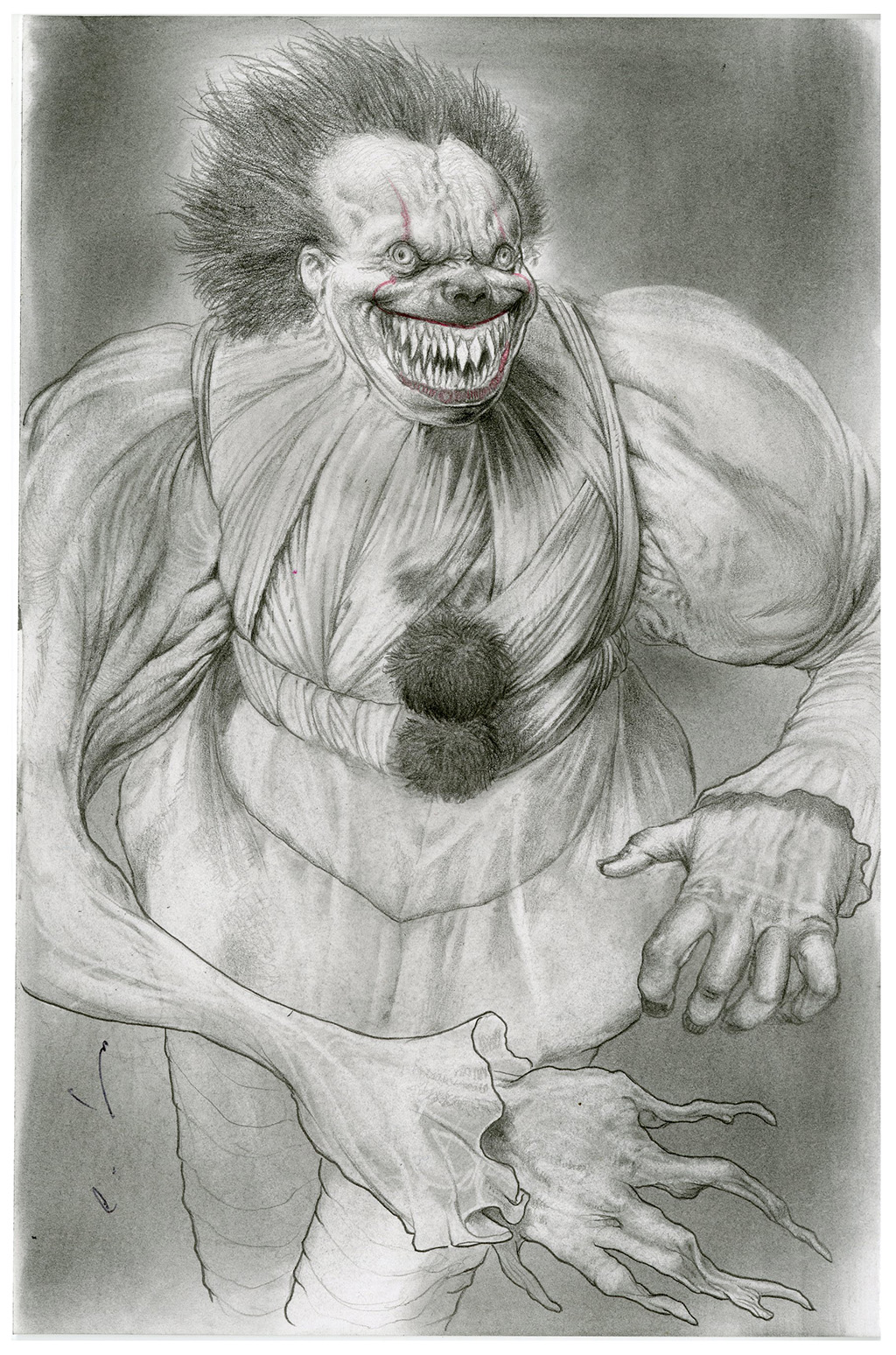

From the magnificent to the grotesque, from the dark to the darkly comedic, the non-human denizens of illustration, film, and TV haunt our dreams as expressions of far more than a mere mortal could convey. Their features, their bodies, their modes of physical communication are designed to speak to us, mostly without words, on a very deep level that conveys and carries story in a way that’s essential to many productions.

The question is: what makes a monster maker? How does someone learn that language and learn to evolve it in a way that brings something new to the conversation? A degree of nostalgia seems essential, looking back to the triumphs of creature creators of the past for inspiration, but it’s the innovators who are able to re-create the sense of wonder that we’re craving by bringing us something new.

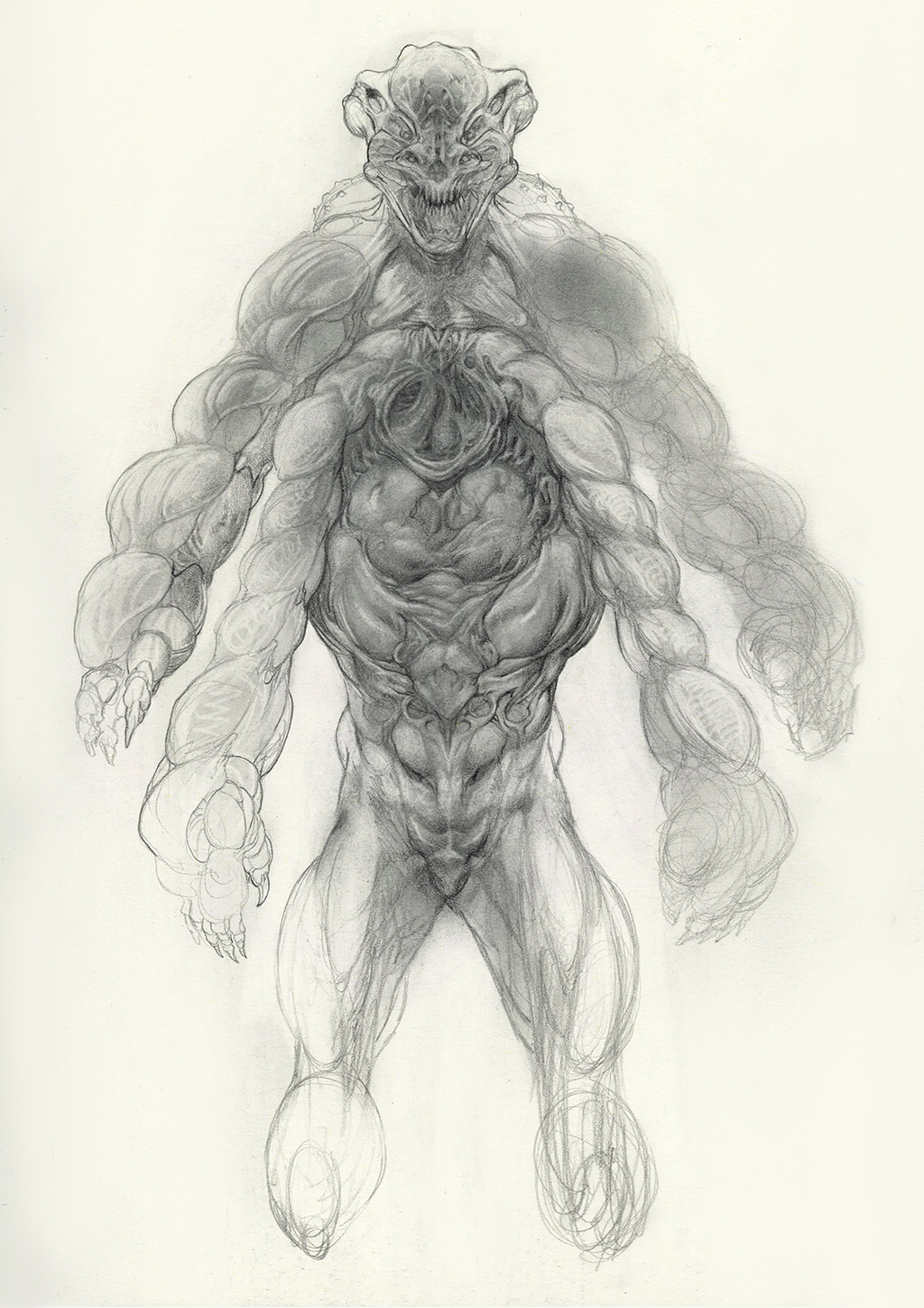

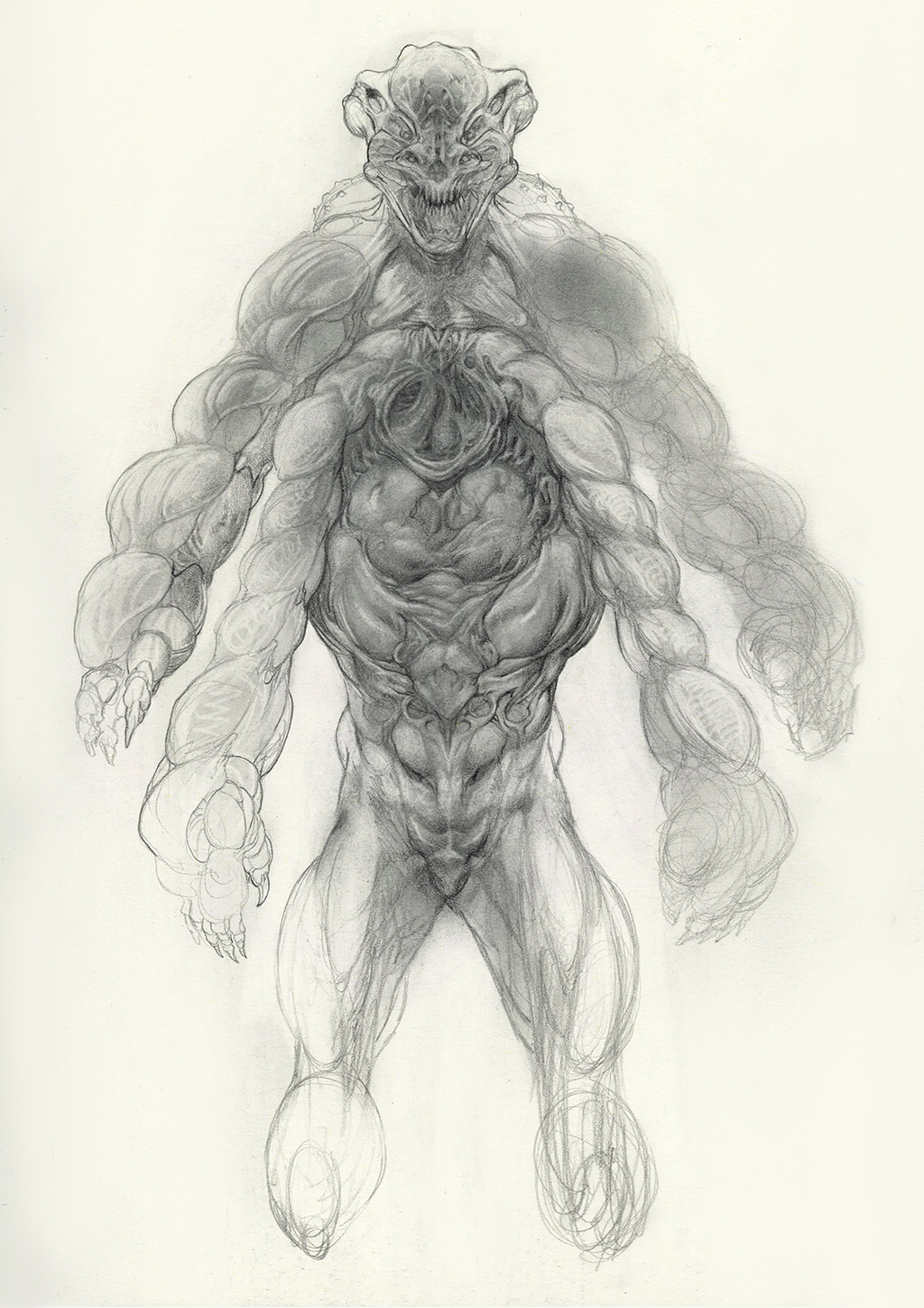

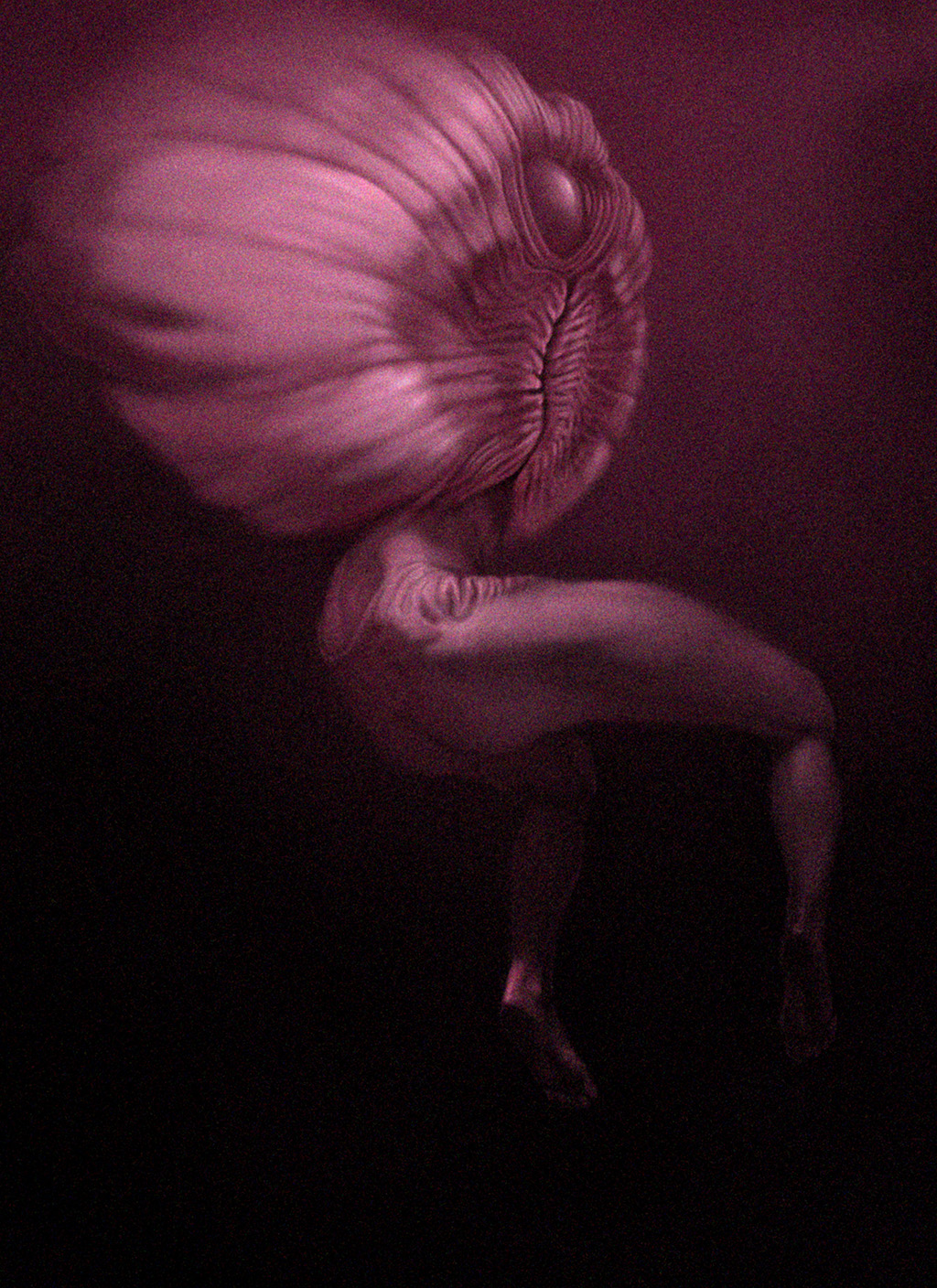

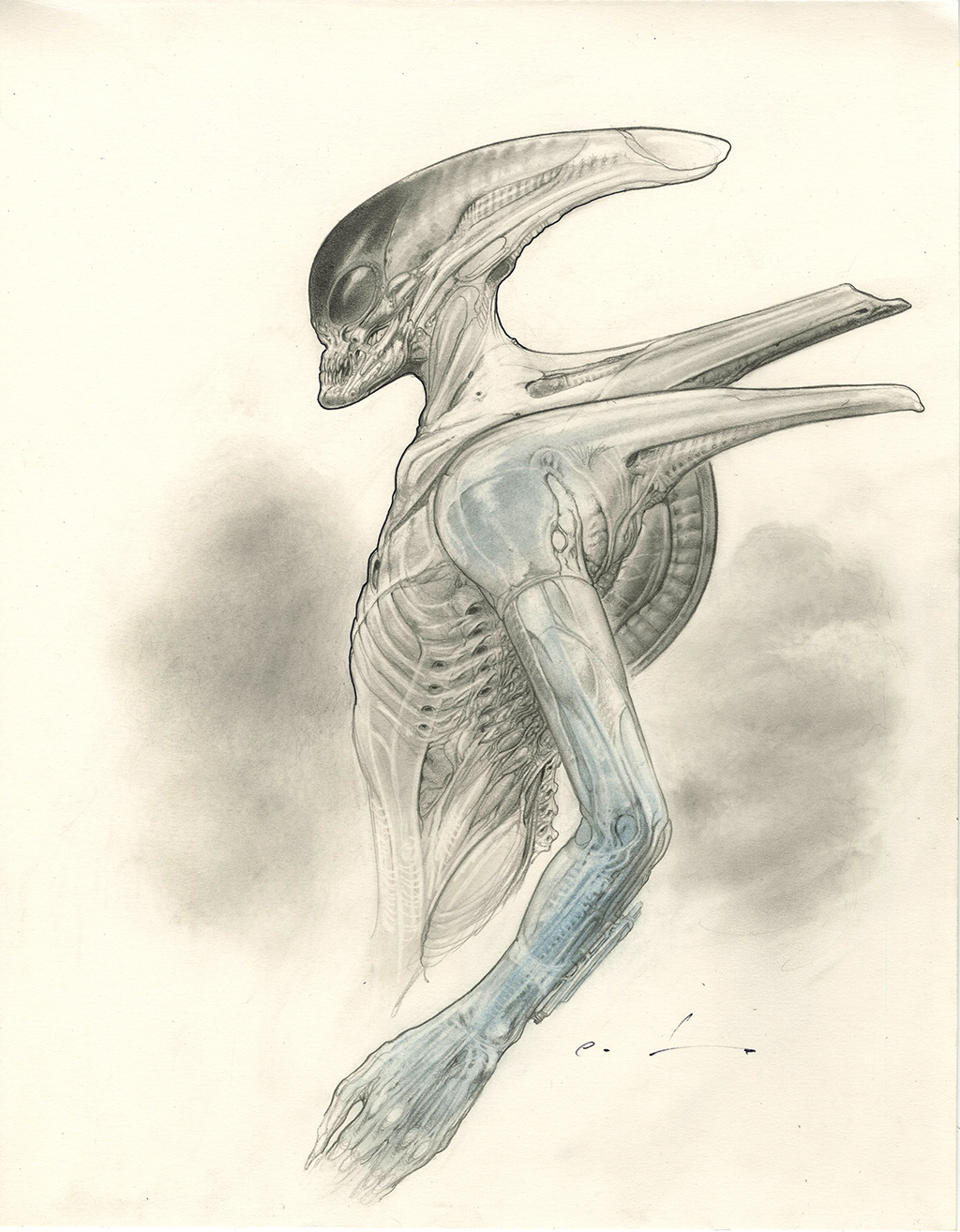

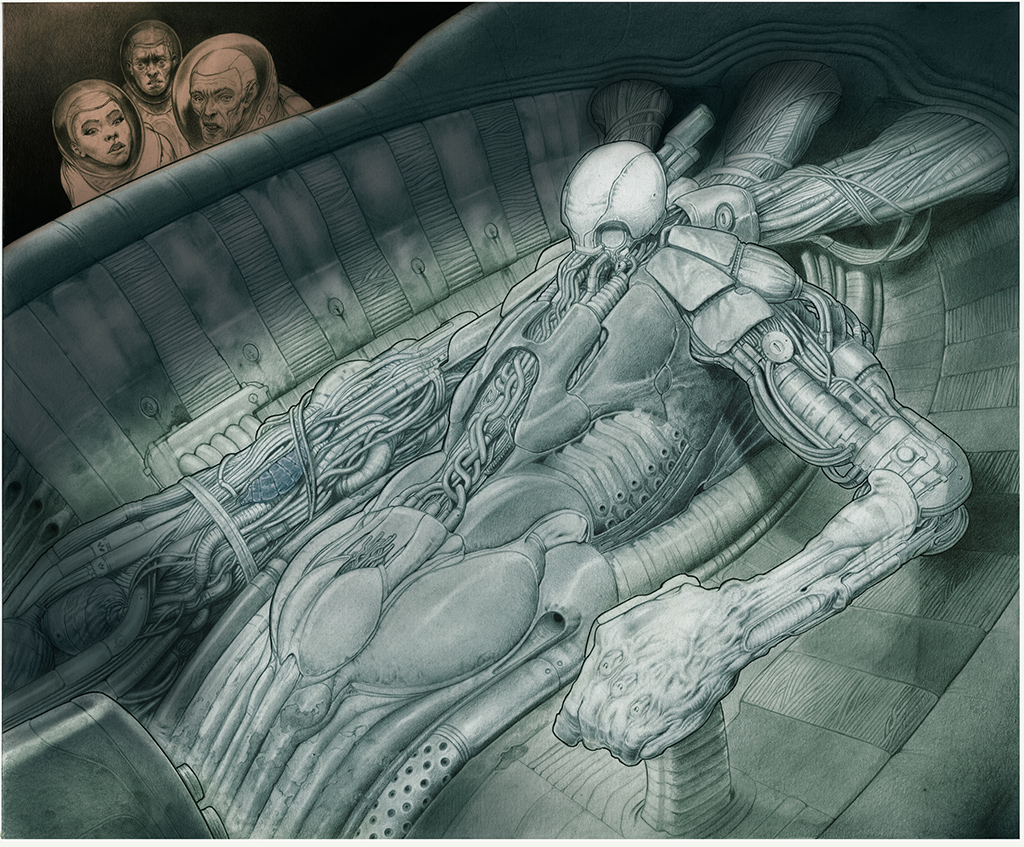

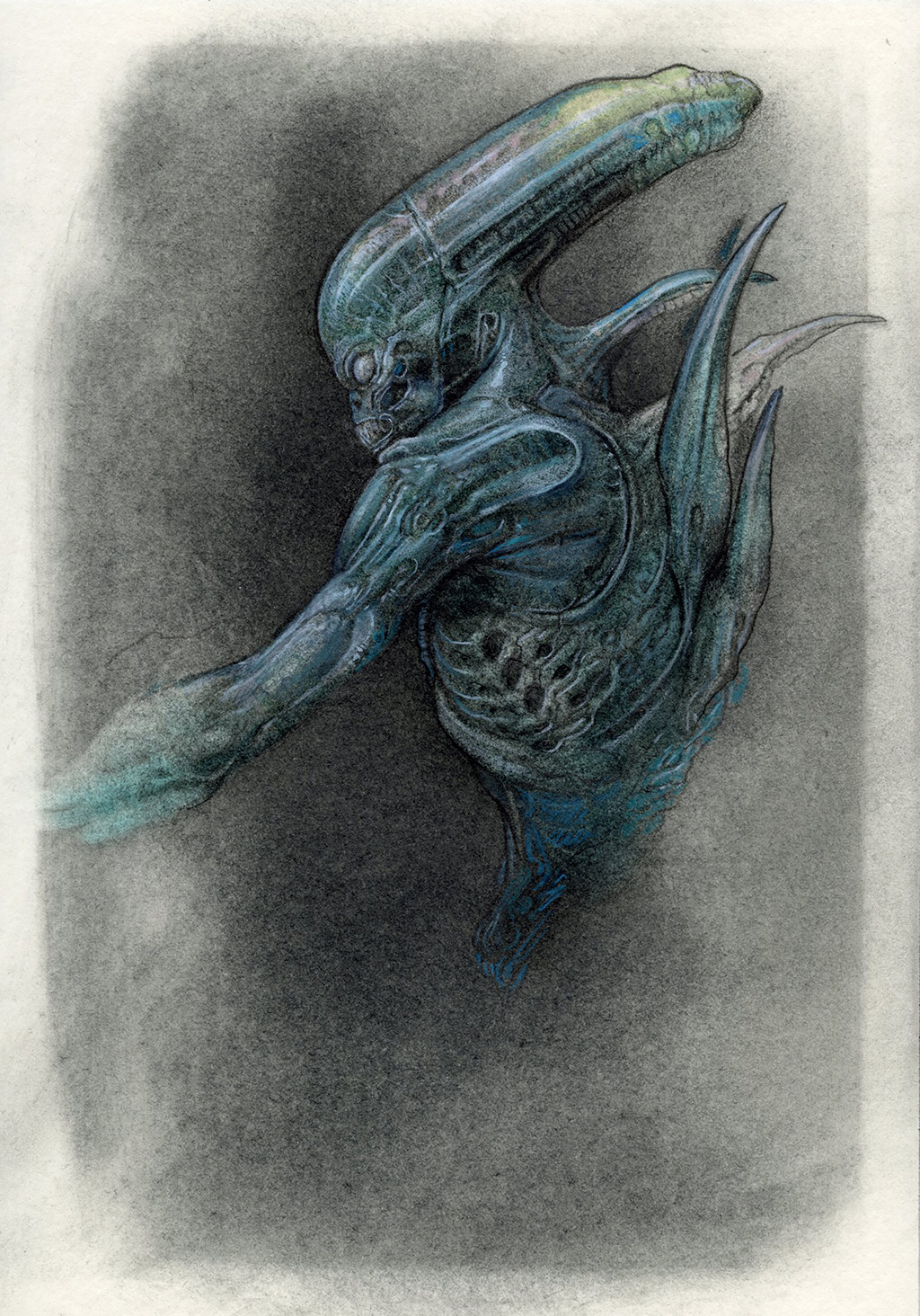

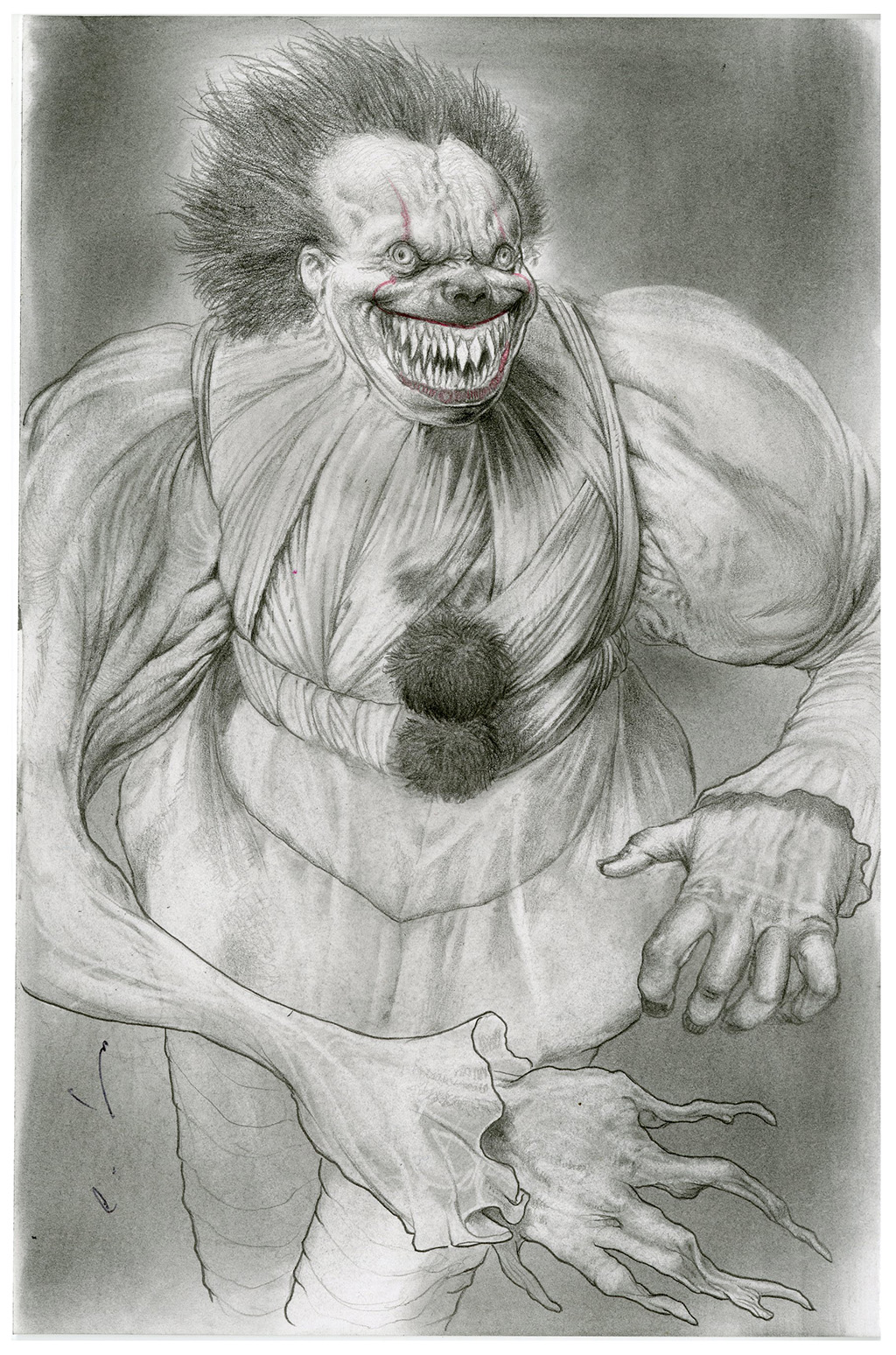

Carlos Huante is a major innovator in the field of design, with over 30 years’ experience in the field, working on TV, film, and video game projects ranging from live action to animation, and all points in between. He’s handled some of the most beloved sci-fi and fantasy properties known to fans, from the Aliens franchise to Bladerunner, and ventured into new territory for big hits with Fantastic Beasts and Arrival.

Huante joins us for a significant walk down memory lane, as well as guided tour of his industry, to unveil just how one does become a designer of the alien and monstrous side of visual media.

HEAVY METAL: What do you think makes something a monster or monstrous? Are there certain traits that you think people expect from sci-fi monsters, particularly?

CARLOS HUANTE: I’ll tell you a story… (laughs) When I was starting school as a child, after first grade my parents decided to transfer me from public school to a parochial grammar school. The education was more advanced and I guess they thought with that, that it would keep me out of trouble... (laughs) I classically became an altar boy and would hang out with the priests sometimes for breakfast before a big service. I won’t tell you that I would sneak a taste of wine while putting the bottles away after service. I never had a bad experience with the priests. They were legit men and good people. My experiences were all, fortunately, great there.

A couple of summers later I went to a type of summer camp which was at Saint Vincent’s Seminary in California. I had the best time there. The brothers were very cool. We had game competitions through the week. Our group was made up of all the misfits, we were exactly like the “Bad News Bears”. The thing is, we won the competition against all the athletically blessed groups. It was an interesting thing to be a part of. So I bring this up for a reason. You’re wondering, “What does all this have to do with the question asked?”…Okay... one night was called “movie night”.

So we had our popcorn and punch, which the brothers called “bug juice”. The movie we watched was Night of the Living Dead. My first time seeing it… a scary movie right? No. The brothers’ reaction to the horror was to laugh at the absurdity. The worse the violence, the louder and more we all laughed. I laughed so hard watching that movie. It marked me for life. They taught me how much fun monster movies and the genre can be. That’s why I take it seriously. I think these movies and the sincere approach towards them gives people the ability to escape real life.

If Night of the Living Dead had been made in a very fake and uninvested manner, people would never have reacted towards it the way they did. It wouldn’t have allowed the hilarious reaction the brothers had at the seminary because it would’ve been stupid and uninteresting, but because they committed themselves to making it believable, it yielded a reaction. Some people got scared, some people laughed… either way the reaction was to the quality of the film and level of commitment. Monsters can be metaphorical, or straight takes on a character that’s written. Either way sincerity in the approach matters. My little part in the process is to design it. I take that part seriously...

HEAVY METAL: How important are tiny details, like bristles or scales, to you as an artist? What kind of overall impact do you think they have on a design or image?

CARLOS HUANTE: Details are secondary, or even tertiary. The most important hit is the first hit. Your first impression is based on primary shapes. When you see someone from far away that you know, you will usually recognize them, even amongst a crowd, because their form is their own. Primary form and proportions are the most important features of anything. That’s the personal base of that specific item, element or being. Details just float on top. Of course they will be much better, and flow with the form when they are handled correctly, but if the base is there, the detail should be pretty smooth sailing.

That being said, I’ve seen creatures ruined by contrasting details, contrasting in idea and personality. The work pipeline that is in use these days, where an artist designs the creature, then it’s passed onto the VFX house, often suffers revision by the many hands that handle it, sometimes unbeknownst to the client whose ability to see the difference is limited. Even if the design is declared as “The” design, the designer is out of the equation, so we can’t art direct to keep everyone in line with the original idea, and what you can end up with is contrasting surface detail and animation. I’ve suffered through this many, many times. Some instances made me feel physically ill for a couple days after seeing the final result in the film... that’s the byproduct of caring, unfortunately.

HEAVY METAL: You’ve been working as an artist for many years, so I know it’s a long story, but can you tell us a little more about how you became such a “monster guy”?

CARLOS HUANTE: I really loved science fiction growing up, as many do, but what I loved about it was the creativity meshed with the science. Of course, being a boy who hated sports, drawing and the arts in general were my outlet. I had many friends and participated in many activities, but as I grew older, I realized I enjoyed the solitude of playing a musical instrument or drawing.

I tried being in a rock band in high school and I just grew tired of the politics, and just wanted to be creative. So, I drifted off and away from that life fast. I liked drawing so much that I’d draw all the time. I loved cars when I was kid (I still do) thanks to my father. He was always buying trucks and/or vans back then and hot rodding them. It was a big reveal when it was finished. So, I drew them almost exclusively at first. The Munsters' “Drag-U-La” coffin car was a beautiful thing to me. That whole period was a great time for hot rods. The Batmobile, Hot Wheels toys… obviously this all lead me to Big Daddy Roth bubble gum cards… monsters and hot rods. But I quickly found that drawing monsters was where I wanted to go.

Once out of high school, and armed with many great sources of inspiration, I knew what I wanted to do for a living. The only problem was that I had no idea how to get in, and more importantly, the position didn’t exist yet. Although artists were hired to design creatures for film throughout film history, they were either makeup artists or generalists that worked in the art department, or Ray Harryhausen, who really only illustrated for his own projects.

Hollywood would later hire comic book artists like Moebius and Bernie Wrightson. When I saw Giger’s personal work, after my mind was blown by the film Alien, I realized two things: one thing was that I could still be an artist as a creature designer, which concerned me in the back of my mind. I had more in common with the type of artist Giger was. I had been a lifelong fan of Salvador Dali. I wasn’t necessarily a fan of dark art at all, but the creativity that had “thought” attached was what was so interesting...

HEAVY METAL: Do you prefer to work in a studio or in a more solitary way?

CARLOS HUANTE: I work from home most of the time, especially when I am drawing. I like to get lost in my own thoughts, but I do enjoy working directly with the client when they have the time. Those can be some of the best and most focused creative sessions while on a project. At the very least, if the budget permits, a good week session with the client after which I like to go off on my own…

HEAVY METAL: Can you tell us a little bit about your relationship with tactile media (pencils, ink, paint) versus digital? I’m assuming you have to work in digital a lot with design, but has that been a transition for you over time?

CARLOS HUANTE: I‘ll tell you... I got into all this because I like to draw. I like to sculpt. I am not someone who loves computers. That being said, I use them in a very limited way. I was a character art director at Industrial Light & Magic, so I understand the digital world, but I’m not really part of it. I see Photoshop as a tool to use in a traditional manner. I see 3D as a tool that I have used only a handful of times, but for nothing of any consequence, just as a token for the politicians in my business who believe it matters in the design phase. Which it doesn’t.

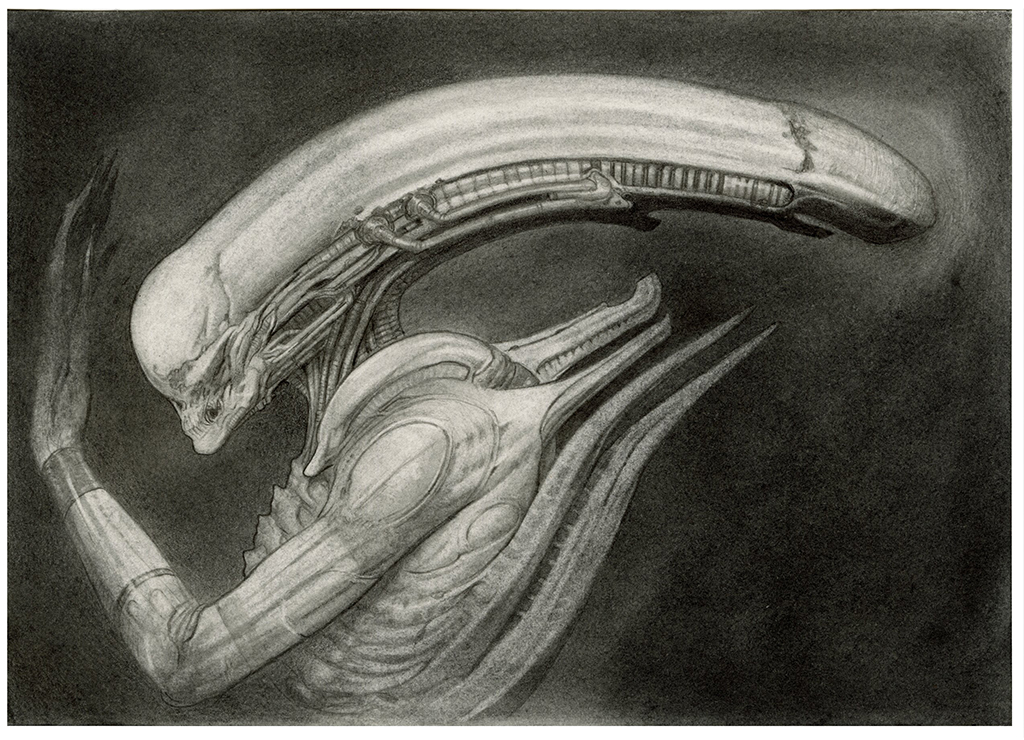

In recent years, I have been “regressing” to graphite on paper more and more, maybe out of rebellion against the digital wash-over the art world has suffered through. After all these years, drawing on paper is still the most honest medium to work in. You can’t hide a bad design with a line drawing. You have to draw every element of the design and you can’t get away with painting tricks, or digital atmosphere, or fancy lighting techniques... or for that matter, a turntable of a very conventional design in 3D. The design will have to sincerely be good naked, as a line drawing. If drawing was the only tool allowed, we’d elevate design in film by 50% at least… just with that one change.

Of course, that would eliminate a good deal of what I call imposters in the field these days… technicians posing as artists. This observation is purely out of love for what is being lost. The business is going through growing pains for sure. Digital has been the word in Hollywood, and most are the producers who just don’t know that digital is only a good production tool. It is not for initial design and ideation. It doesn’t save money in the design phase. Understand why this is a gripe. Imagine people who are not gifted sculptors or draftsmen, who merely know how to navigate the software, being given positions as designers. It’s artistically abominable. I know some of the best modelers in the world who agree with me. I love them for their part in the process, but not as designers. It disrespects them and their expertise and cheapens the entire process.

Years ago, when I was first coming up in the business as a professional, in the pre-digital era, I was critical about illustrators being hired to design creatures instead of designers. The illustrators would hide the design behind a render and lose most of the image in shadow, which makes for a dynamic and fun picture, but conceals the problems of the design. Design is a completely different expertise.

Then digital came along and turned that up to 100, and every child who could push a stylus flooded the business with regurgitated ideas from designs we had already done years prior. They still do. I see proportions and design elements on characters for jobs that are mere regurgitations of everything we came up with years ago, which suggests to me that there’s no thinking, integrity… no fire, no interest in anything other than getting a job, and/or recognition. It’s a shame. I know there are talented people out there, but they are not being pushed or required to do anything more than just achieve what has already been done and done successfully. It’s very boring. Once in a while I see something that’s interesting... but not as often as I’d like.

HEAVY METAL: How do you make a living in your field? Is it a case of taking on one big project at a time, or do you find yourself working on several at a time?

CARLOS HUANTE: Both. The unglamorous part is that I am making a living. In the last part of the ‘80s and first part of the ‘90s, what I would do is work for TV animation, designing characters during the TV season months, and then in off season, freelance for live action film. When I decided to get married, I was back working on the Ghostbusters animated series. While there, I met someone who knew people at a place called Dinamation. It was a place where animatronic dinosaurs were made for museums all around the world.

So, we went and visited the place just for the fun of it. But I was told to take my portfolio, which I did. I was overwhelmed by the scale they were working on in there. But I showed my work and I was asked to take the job of illustrator there, which of course I did. Fortunately, I had such a good rapport with my director and art director on Ghostbusters that they allowed me to remain working for them full-time from home knowing that I had taken the other gig.

I have to take almost all jobs when they come in. Because what can happen is, the next project that was promised may never show up, and then I’m out of work. Which happens more often than you’d believe. This type of work is not for the faint of heart. It’s very tough. You never really know when you’ll be working or not. So you have to say yes to everything. The client that you have that loves you may, one day after working smoothly for weeks, just stop responding, and you’re done without notice. It makes it hard to take vacations. Heh...

HEAVY METAL: Can you talk a little bit about your process working on a property like Prometheus? What kind of aesthetic were you presented with, and what kind of ideas did that generate for you?

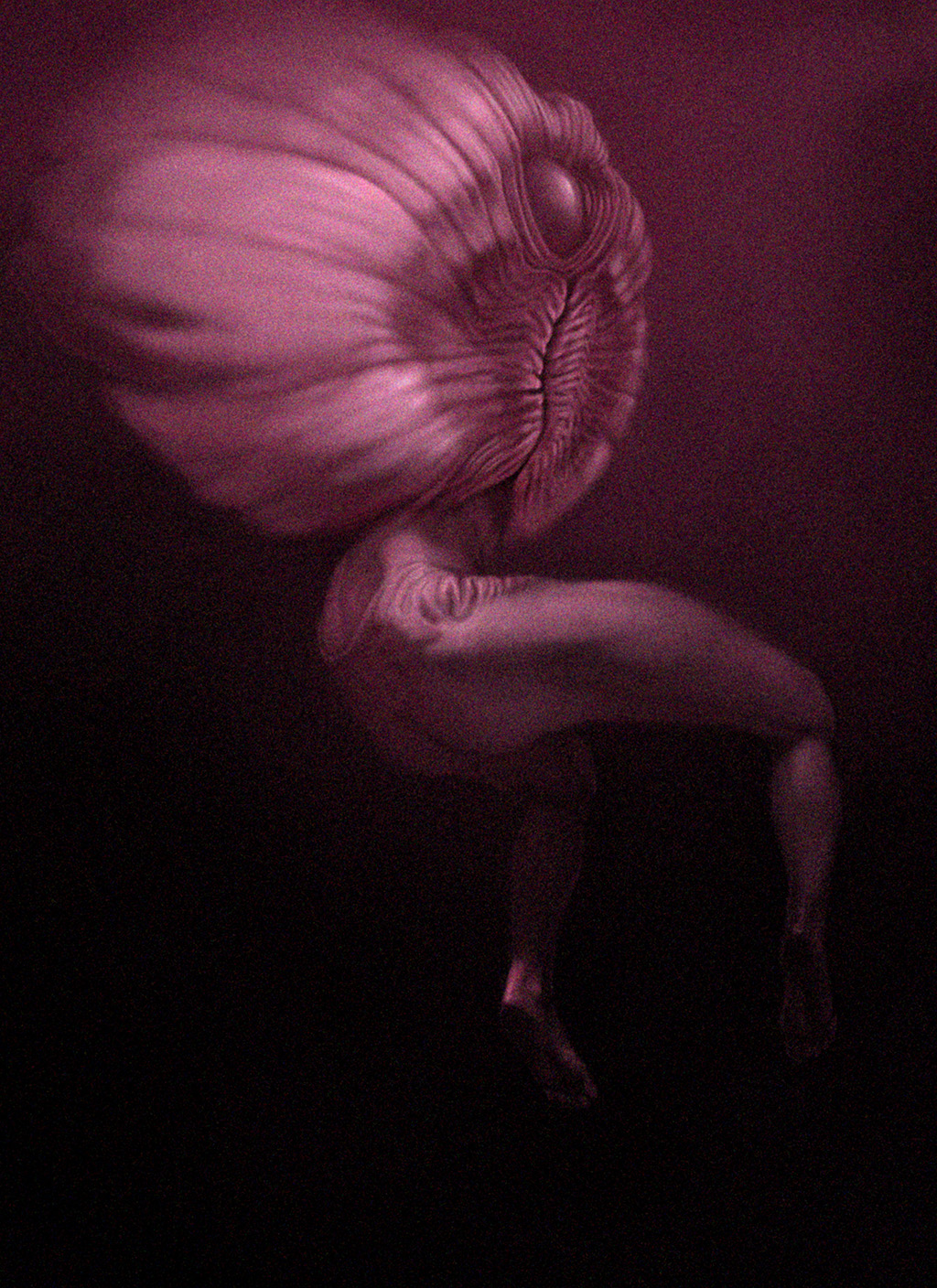

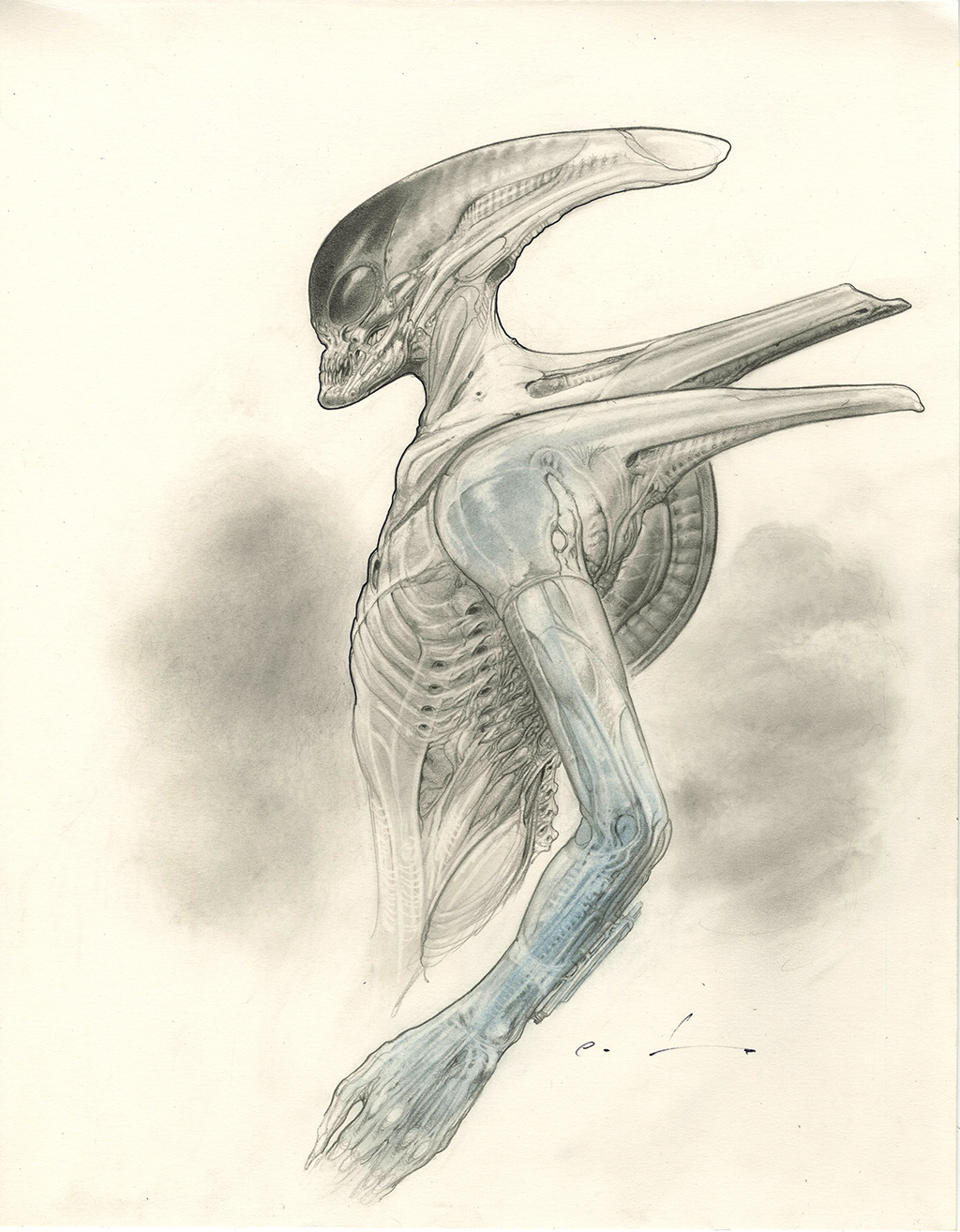

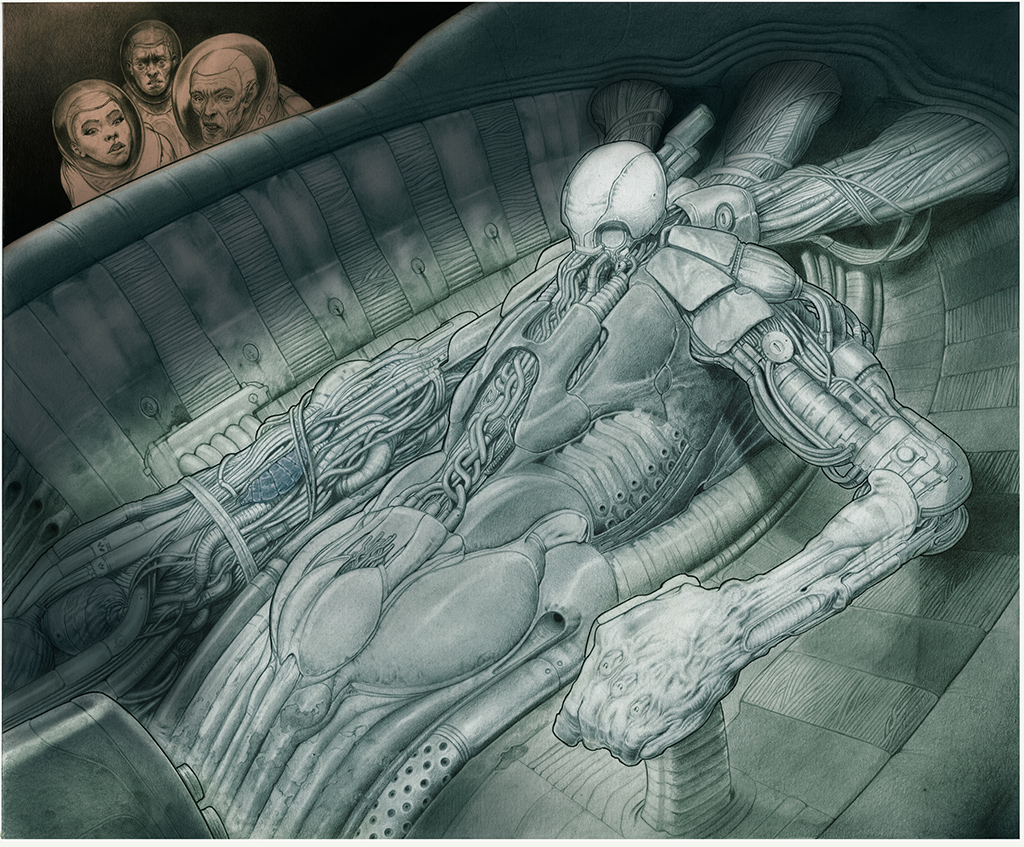

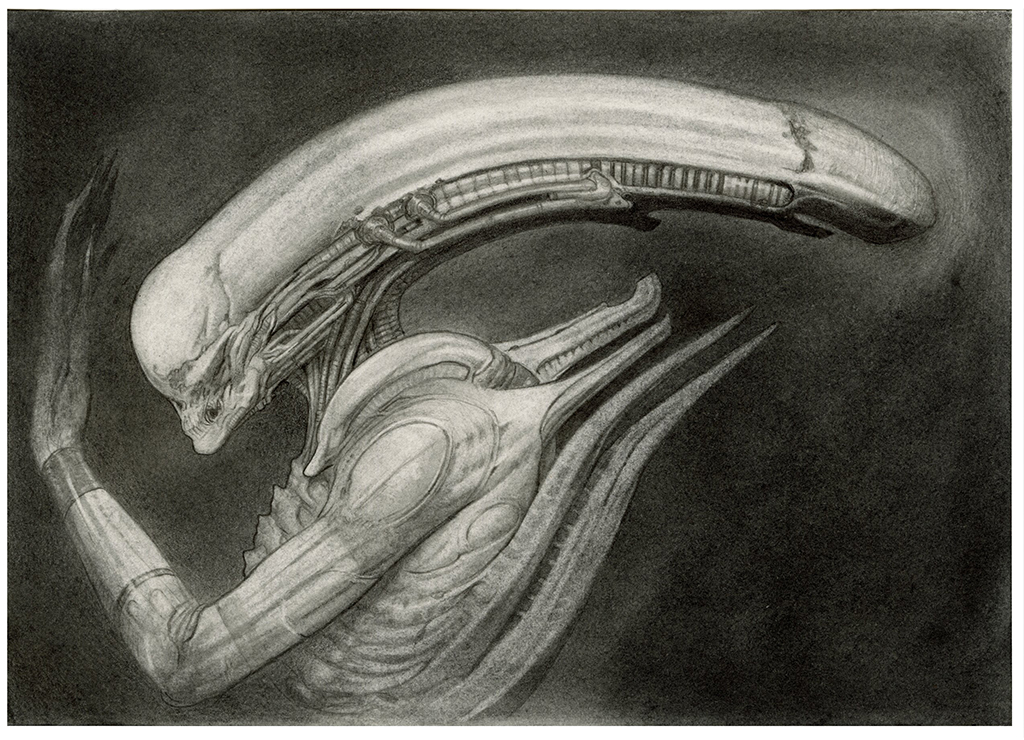

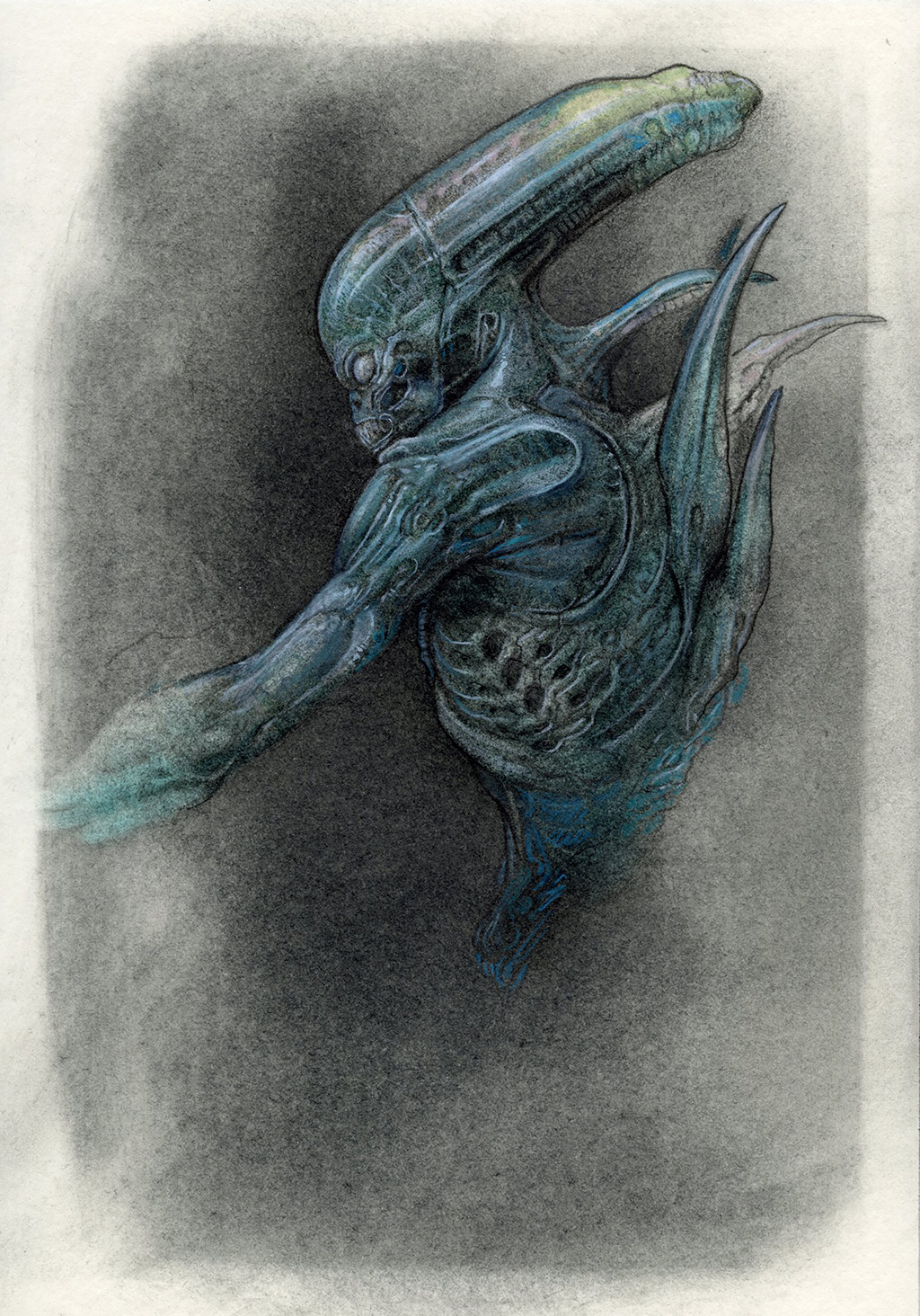

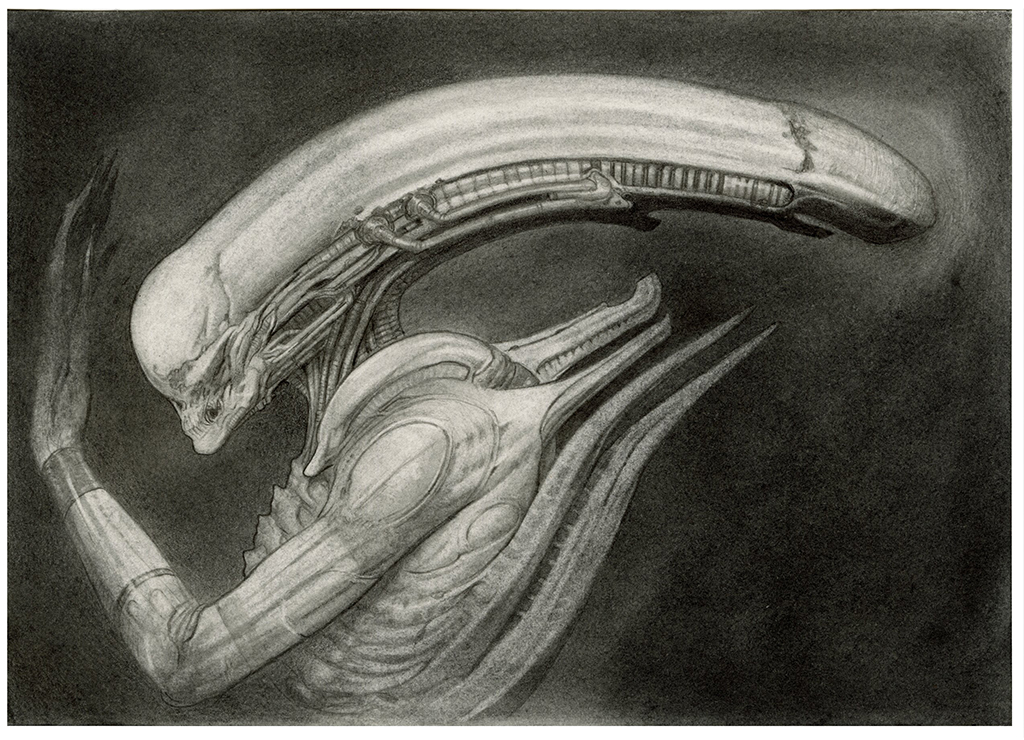

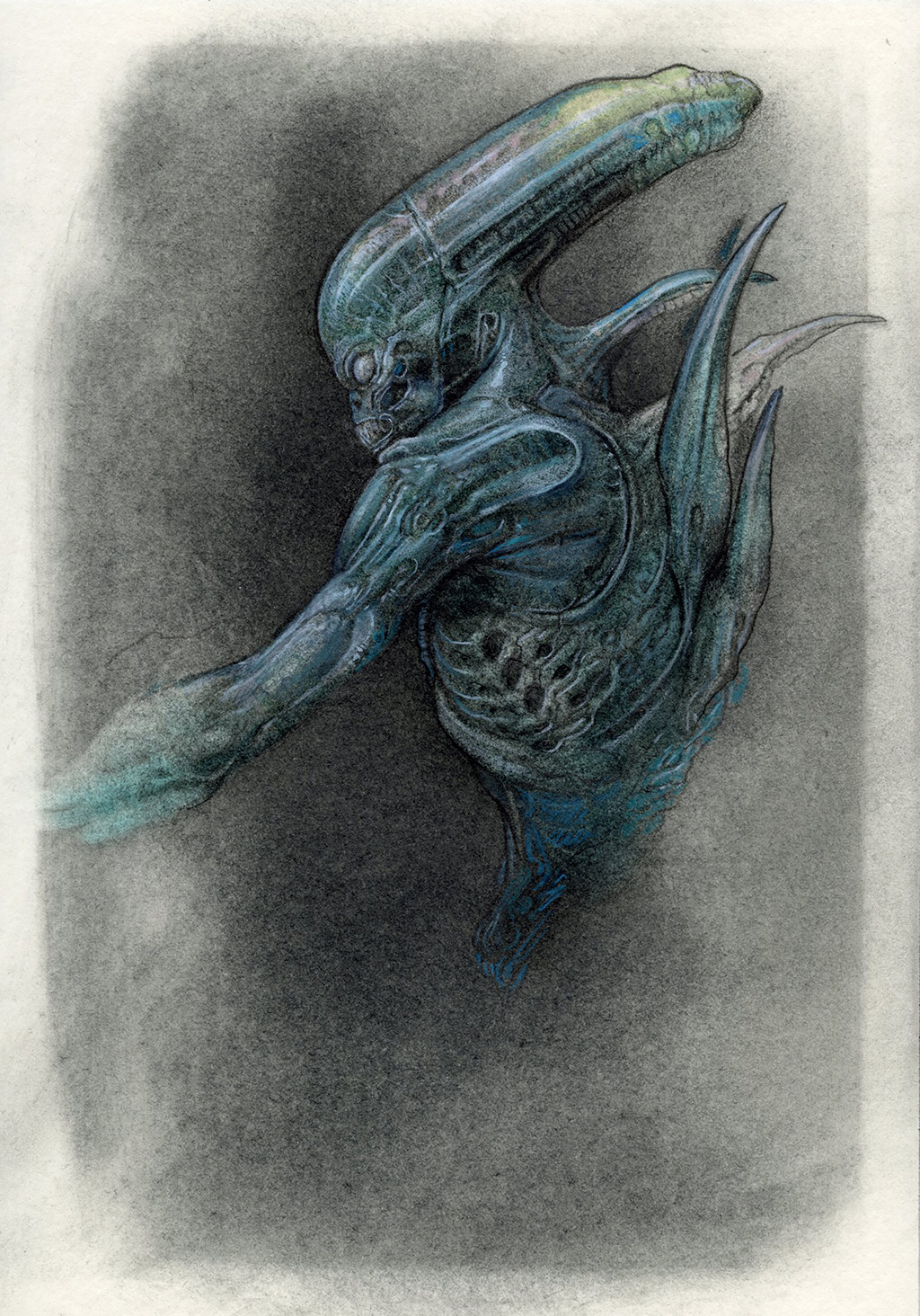

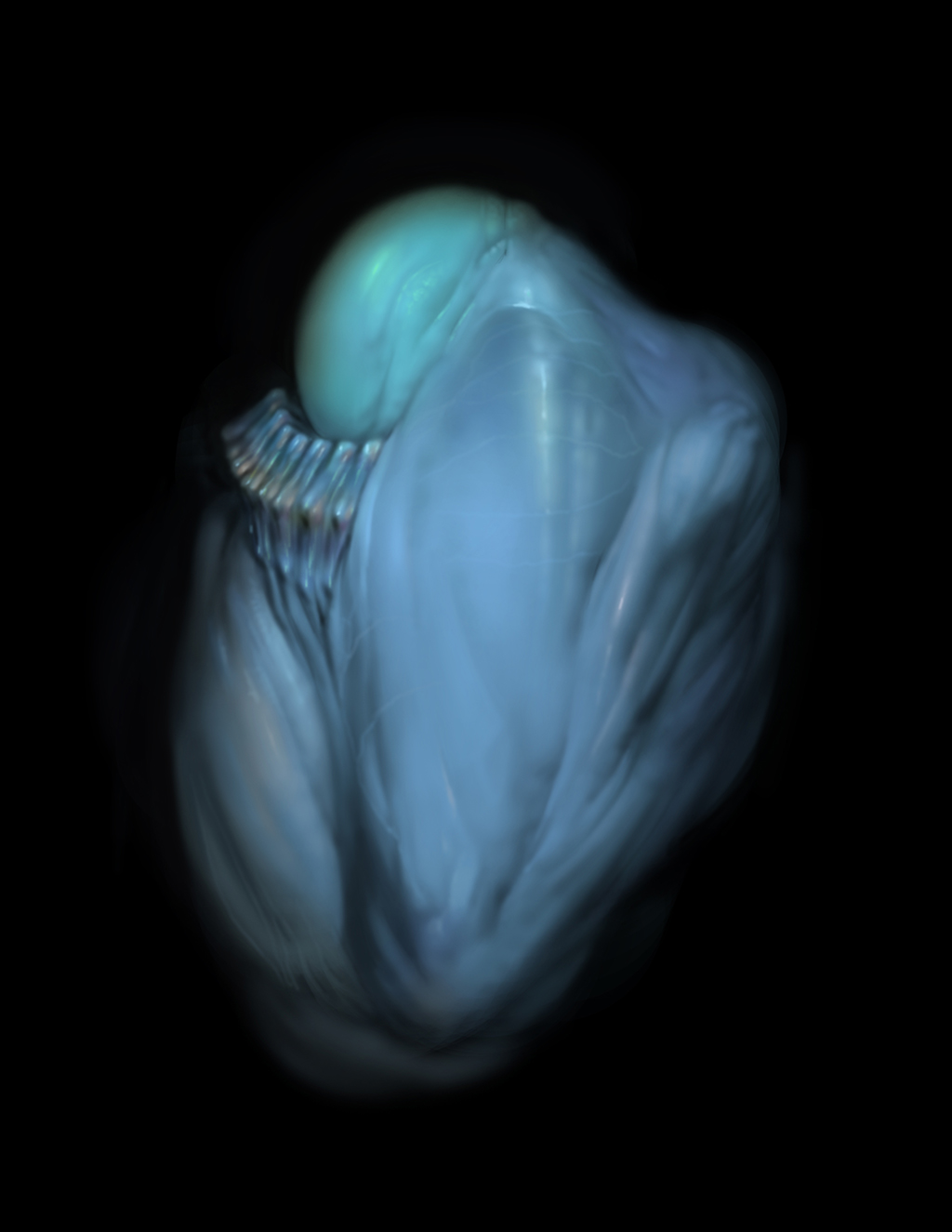

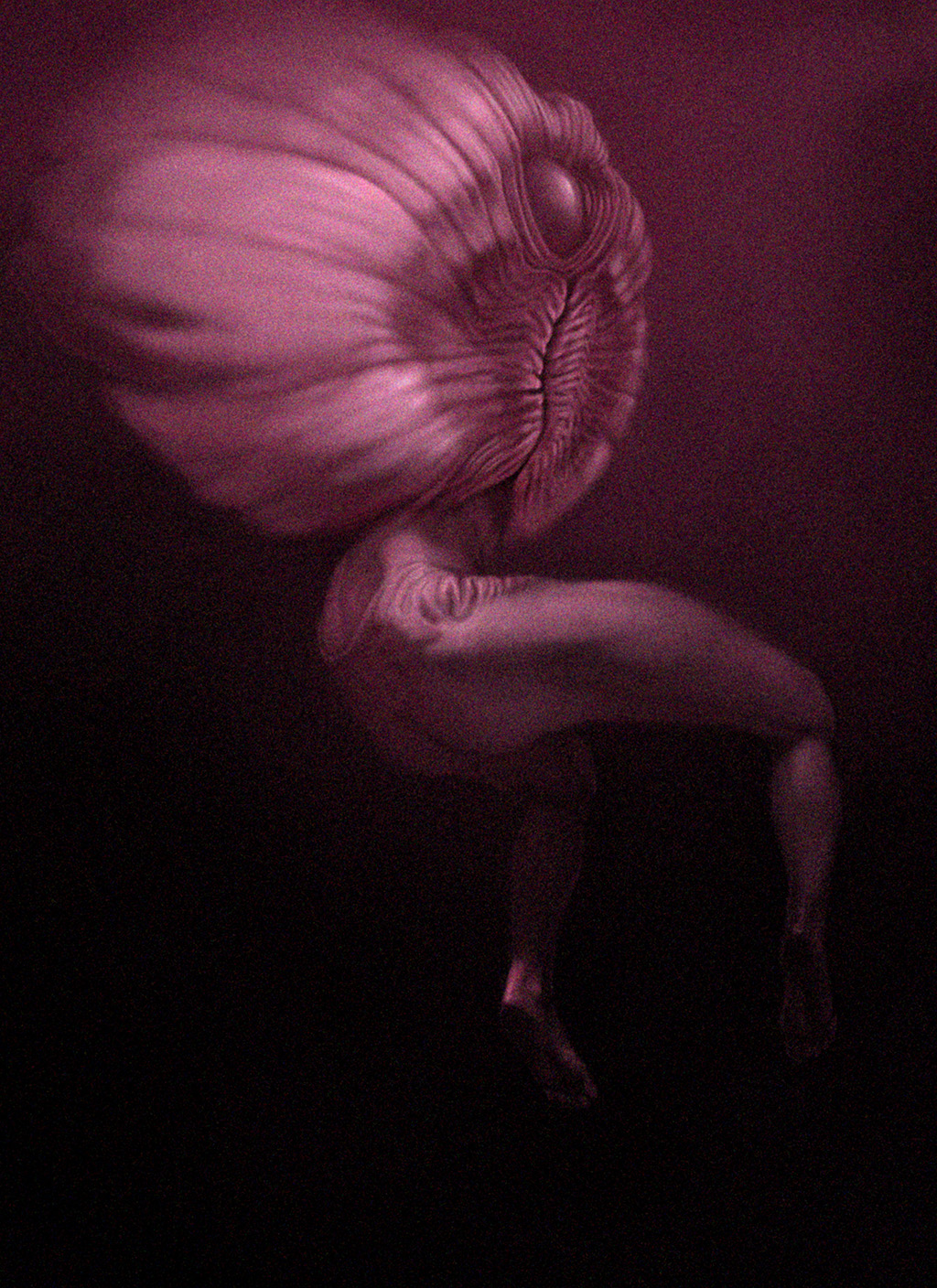

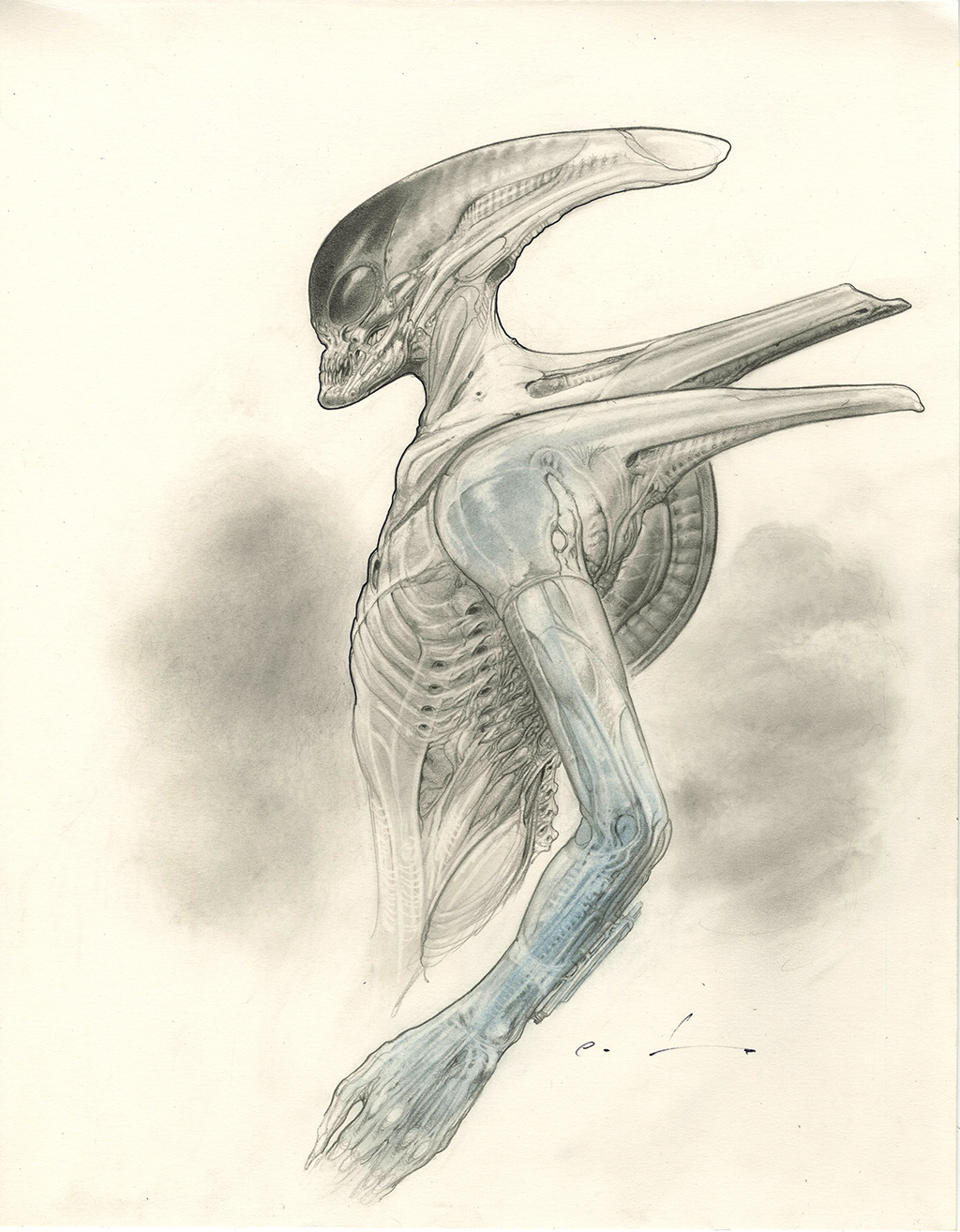

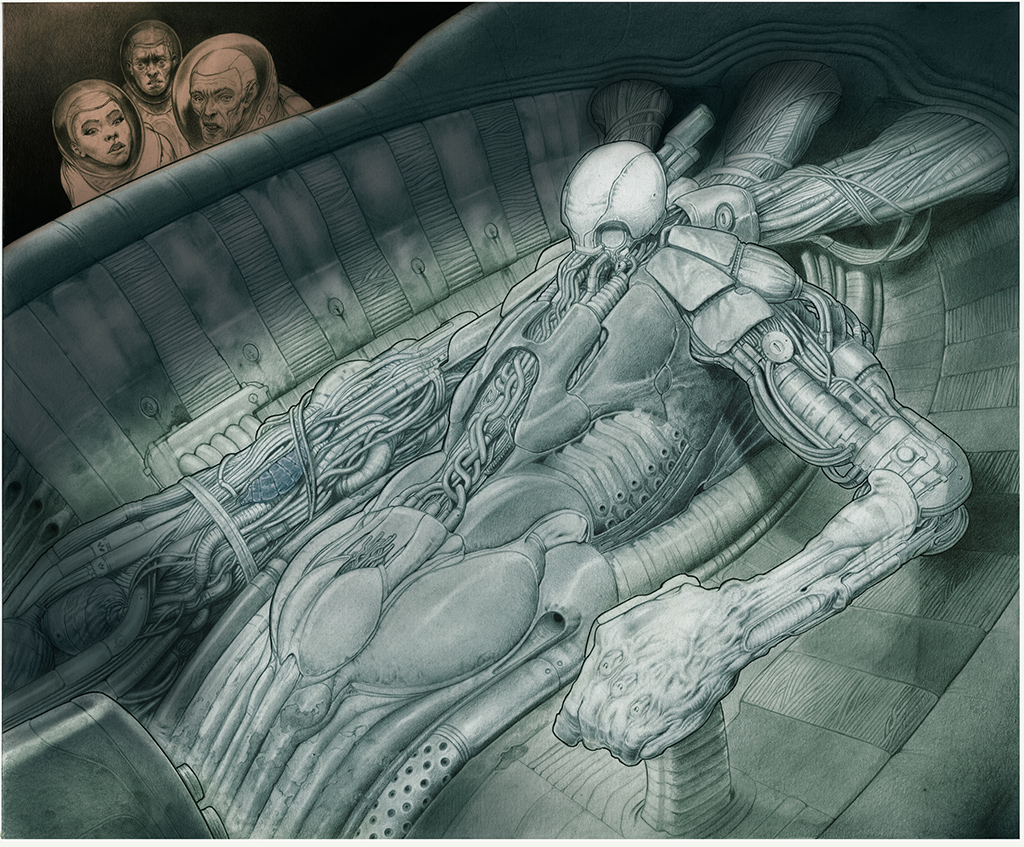

CARLOS HUANTE: For Prometheus in particular, the movie was “Alien prequel” and so we approached it as that. To start, my aesthetic bookends were Giger on one side and Giger on the other ;). I was going to make sure, whatever I did, that it would match up to Giger’s aesthetic. I wasn’t going to restyle the design language. In my opinion, all the new designs had to feel like Giger’s work. Ridley Scott had some ideas, but they were evolving. The idea of what would become the engineers were more like giant whales at first… less like humanoids... I had so many rounds of ammunition walking into that project that I was ready for a war.

I was essentially allowed to just run free. Ridley is such a good boss to have for a creative. He encouraged all my thinking and allowed me to speak to his ideas and add stuff. Whether they were used or not, in the end, is beside the point of the process being so organic. The “Deacon” literally came out of a drawing that I offered them in one round. I was thinking of a precursor to the Alien in the original film, and also the rules of why it existed as it did. I was writing notes on the plane before my meetings with Ridley, very fun stuff. Working on big, inspired movies like that is the best, there are very few. Men In Black, the first movie, was kind of like that as well because of Rick Baker. Rick Baker was equally a great boss. He allowed me to do whatever came into my mind and he shielded me from the politics of the studio. Denis Villeneuve was also one of those, and the situation on Arrival was so much fun. Denis and I pushed the ideas out and around to get as abstract, within reason, as we could...

HEAVY METAL: What kind of differences do you encounter working on a big blockbuster-type film project (AVP, Bladerunner 2, Fantastic Beasts 2) in comparison to working on a more genre or niche project (Arrival, Alice in Wonderland)?

CARLOS HUANTE: Those big blockbusters you mentioned had the luxury of already being established, which was a big challenge out of the way. Although working within established parameters can be a blessing or a curse, depending on how well the original project was designed. The source, or original versions of the those films you mentioned, fortunately, were all very, very well done, even iconic, which gave me an immediate and direct line for my imagination. Alice in Wonderland also is such a well-established story with illustrated books and the animated movie, again, iconic. Arthur Rackham, the poem of the Jabberwocky, and Disney in their heyday. Just great stuff. It was rich with established inspiration. Arrival is an example of a totally open-ended project that had no history and thus required a lot of thinking. Arrival-type projects are the hardest, but yield the biggest rewards.

HEAVY METAL: Have you had to expand and adapt your craft to work in video games, or do you find there is much in common with film and TV projects?

CARLOS HUANTE: There is a lot in common with all, although, with some minor approach shifts which make the distinctions between them all. So the creative approach is almost the same depending on the client, as in the director, art director, showrunner, VFX lead, producer, etc. and depending on whether whoever that person is that has the main voice on the project understands the project, and is able to communicate what the vibe of the project is, and/or, what they want.

HEAVY METAL: Who are your creative heroes? You mentioned that you’re a Bernie Wrightson fan...

CARLOS HUANTE: It’s a big list... but... just to name a few… yes, Bernie Wrightson. I really love his work. Muck Monster was probably the best period for me, personally. He had some of the Frankenstein in there, but with some of the fun, looser style from the earlier Swamp Thing. I loved all periods, but that one was my favorite of his.

I have to start this by saying that it was my older cousin, Johnny Vasquez, who inspired me to draw. He took the time to sit and draw with a child like me. My memory of his drawings are, “Wow”. He is my earliest artistic hero. I talk about him in my book Monstruo.

The very first art book I bought on my own (I was still a child) was Breaking the Rules of Watercolor by Burt Silverman. It is still one of my favorite art books. Then, my first book as a professional was The Art of Honore Daumier. The earliest professional influences for me were Alex Toth, Jack Kirby, and John Buscema. But then, Möebius, Giger, Gaetano Liberatore, Phillipe Druillet, Dali, Kent Williams, Bill Sienkiewicz, Richard Corben, Frank Frazzetta, Ray Harryhausen’s drawings as much as his FX animation work. Gustave Dore was/is huge to me, Beksinski, Stanislav Szukalski (one of the greatest). JMW Turner is a very big deal to me, Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky, Goya, Michelangelo, Bernini (the son), Leonardo, Rembrandt, Rodin, and Rembrandt Bugatti, and Paolo Troubetzkoy, who are everything to me as far as sculpture.

CHRIS HUANTE Interview

From the magnificent to the grotesque, from the dark to the darkly comedic, the non-human denizens of illustration, film, and TV haunt our dreams as expressions of far more than a mere mortal could convey. Their features, their bodies, their modes of physical communication are designed to speak to us, mostly without words, on a very deep level that conveys and carries story in a way that’s essential to many productions.

The question is: what makes a monster maker? How does someone learn that language and learn to evolve it in a way that brings something new to the conversation? A degree of nostalgia seems essential, looking back to the triumphs of creature creators of the past for inspiration, but it’s the innovators who are able to re-create the sense of wonder that we’re craving by bringing us something new.

Carlos Huante is a major innovator in the field of design, with over 30 years’ experience in the field, working on TV, film, and video game projects ranging from live action to animation, and all points in between. He’s handled some of the most beloved sci-fi and fantasy properties known to fans, from the Aliens franchise to Bladerunner, and ventured into new territory for big hits with Fantastic Beasts and Arrival.

Huante joins us for a significant walk down memory lane, as well as guided tour of his industry, to unveil just how one does become a designer of the alien and monstrous side of visual media.

HEAVY METAL: What do you think makes something a monster or monstrous? Are there certain traits that you think people expect from sci-fi monsters, particularly?

CARLOS HUANTE: I’ll tell you a story… (laughs) When I was starting school as a child, after first grade my parents decided to transfer me from public school to a parochial grammar school. The education was more advanced and I guess they thought with that, that it would keep me out of trouble... (laughs) I classically became an altar boy and would hang out with the priests sometimes for breakfast before a big service. I won’t tell you that I would sneak a taste of wine while putting the bottles away after service. I never had a bad experience with the priests. They were legit men and good people. My experiences were all, fortunately, great there.

A couple of summers later I went to a type of summer camp which was at Saint Vincent’s Seminary in California. I had the best time there. The brothers were very cool. We had game competitions through the week. Our group was made up of all the misfits, we were exactly like the “Bad News Bears”. The thing is, we won the competition against all the athletically blessed groups. It was an interesting thing to be a part of. So I bring this up for a reason. You’re wondering, “What does all this have to do with the question asked?”…Okay... one night was called “movie night”.

So we had our popcorn and punch, which the brothers called “bug juice”. The movie we watched was Night of the Living Dead. My first time seeing it… a scary movie right? No. The brothers’ reaction to the horror was to laugh at the absurdity. The worse the violence, the louder and more we all laughed. I laughed so hard watching that movie. It marked me for life. They taught me how much fun monster movies and the genre can be. That’s why I take it seriously. I think these movies and the sincere approach towards them gives people the ability to escape real life.

If Night of the Living Dead had been made in a very fake and uninvested manner, people would never have reacted towards it the way they did. It wouldn’t have allowed the hilarious reaction the brothers had at the seminary because it would’ve been stupid and uninteresting, but because they committed themselves to making it believable, it yielded a reaction. Some people got scared, some people laughed… either way the reaction was to the quality of the film and level of commitment. Monsters can be metaphorical, or straight takes on a character that’s written. Either way sincerity in the approach matters. My little part in the process is to design it. I take that part seriously...

HEAVY METAL: How important are tiny details, like bristles or scales, to you as an artist? What kind of overall impact do you think they have on a design or image?

CARLOS HUANTE: Details are secondary, or even tertiary. The most important hit is the first hit. Your first impression is based on primary shapes. When you see someone from far away that you know, you will usually recognize them, even amongst a crowd, because their form is their own. Primary form and proportions are the most important features of anything. That’s the personal base of that specific item, element or being. Details just float on top. Of course they will be much better, and flow with the form when they are handled correctly, but if the base is there, the detail should be pretty smooth sailing.

That being said, I’ve seen creatures ruined by contrasting details, contrasting in idea and personality. The work pipeline that is in use these days, where an artist designs the creature, then it’s passed onto the VFX house, often suffers revision by the many hands that handle it, sometimes unbeknownst to the client whose ability to see the difference is limited. Even if the design is declared as “The” design, the designer is out of the equation, so we can’t art direct to keep everyone in line with the original idea, and what you can end up with is contrasting surface detail and animation. I’ve suffered through this many, many times. Some instances made me feel physically ill for a couple days after seeing the final result in the film... that’s the byproduct of caring, unfortunately.

HEAVY METAL: You’ve been working as an artist for many years, so I know it’s a long story, but can you tell us a little more about how you became such a “monster guy”?

CARLOS HUANTE: I really loved science fiction growing up, as many do, but what I loved about it was the creativity meshed with the science. Of course, being a boy who hated sports, drawing and the arts in general were my outlet. I had many friends and participated in many activities, but as I grew older, I realized I enjoyed the solitude of playing a musical instrument or drawing.

I tried being in a rock band in high school and I just grew tired of the politics, and just wanted to be creative. So, I drifted off and away from that life fast. I liked drawing so much that I’d draw all the time. I loved cars when I was kid (I still do) thanks to my father. He was always buying trucks and/or vans back then and hot rodding them. It was a big reveal when it was finished. So, I drew them almost exclusively at first. The Munsters' “Drag-U-La” coffin car was a beautiful thing to me. That whole period was a great time for hot rods. The Batmobile, Hot Wheels toys… obviously this all lead me to Big Daddy Roth bubble gum cards… monsters and hot rods. But I quickly found that drawing monsters was where I wanted to go.

Once out of high school, and armed with many great sources of inspiration, I knew what I wanted to do for a living. The only problem was that I had no idea how to get in, and more importantly, the position didn’t exist yet. Although artists were hired to design creatures for film throughout film history, they were either makeup artists or generalists that worked in the art department, or Ray Harryhausen, who really only illustrated for his own projects.

Hollywood would later hire comic book artists like Moebius and Bernie Wrightson. When I saw Giger’s personal work, after my mind was blown by the film Alien, I realized two things: one thing was that I could still be an artist as a creature designer, which concerned me in the back of my mind. I had more in common with the type of artist Giger was. I had been a lifelong fan of Salvador Dali. I wasn’t necessarily a fan of dark art at all, but the creativity that had “thought” attached was what was so interesting...

HEAVY METAL: Do you prefer to work in a studio or in a more solitary way?

CARLOS HUANTE: I work from home most of the time, especially when I am drawing. I like to get lost in my own thoughts, but I do enjoy working directly with the client when they have the time. Those can be some of the best and most focused creative sessions while on a project. At the very least, if the budget permits, a good week session with the client after which I like to go off on my own…

HEAVY METAL: Can you tell us a little bit about your relationship with tactile media (pencils, ink, paint) versus digital? I’m assuming you have to work in digital a lot with design, but has that been a transition for you over time?

CARLOS HUANTE: I‘ll tell you... I got into all this because I like to draw. I like to sculpt. I am not someone who loves computers. That being said, I use them in a very limited way. I was a character art director at Industrial Light & Magic, so I understand the digital world, but I’m not really part of it. I see Photoshop as a tool to use in a traditional manner. I see 3D as a tool that I have used only a handful of times, but for nothing of any consequence, just as a token for the politicians in my business who believe it matters in the design phase. Which it doesn’t.

In recent years, I have been “regressing” to graphite on paper more and more, maybe out of rebellion against the digital wash-over the art world has suffered through. After all these years, drawing on paper is still the most honest medium to work in. You can’t hide a bad design with a line drawing. You have to draw every element of the design and you can’t get away with painting tricks, or digital atmosphere, or fancy lighting techniques... or for that matter, a turntable of a very conventional design in 3D. The design will have to sincerely be good naked, as a line drawing. If drawing was the only tool allowed, we’d elevate design in film by 50% at least… just with that one change.

Of course, that would eliminate a good deal of what I call imposters in the field these days… technicians posing as artists. This observation is purely out of love for what is being lost. The business is going through growing pains for sure. Digital has been the word in Hollywood, and most are the producers who just don’t know that digital is only a good production tool. It is not for initial design and ideation. It doesn’t save money in the design phase. Understand why this is a gripe. Imagine people who are not gifted sculptors or draftsmen, who merely know how to navigate the software, being given positions as designers. It’s artistically abominable. I know some of the best modelers in the world who agree with me. I love them for their part in the process, but not as designers. It disrespects them and their expertise and cheapens the entire process.

Years ago, when I was first coming up in the business as a professional, in the pre-digital era, I was critical about illustrators being hired to design creatures instead of designers. The illustrators would hide the design behind a render and lose most of the image in shadow, which makes for a dynamic and fun picture, but conceals the problems of the design. Design is a completely different expertise.

Then digital came along and turned that up to 100, and every child who could push a stylus flooded the business with regurgitated ideas from designs we had already done years prior. They still do. I see proportions and design elements on characters for jobs that are mere regurgitations of everything we came up with years ago, which suggests to me that there’s no thinking, integrity… no fire, no interest in anything other than getting a job, and/or recognition. It’s a shame. I know there are talented people out there, but they are not being pushed or required to do anything more than just achieve what has already been done and done successfully. It’s very boring. Once in a while I see something that’s interesting... but not as often as I’d like.

HEAVY METAL: How do you make a living in your field? Is it a case of taking on one big project at a time, or do you find yourself working on several at a time?

CARLOS HUANTE: Both. The unglamorous part is that I am making a living. In the last part of the ‘80s and first part of the ‘90s, what I would do is work for TV animation, designing characters during the TV season months, and then in off season, freelance for live action film. When I decided to get married, I was back working on the Ghostbusters animated series. While there, I met someone who knew people at a place called Dinamation. It was a place where animatronic dinosaurs were made for museums all around the world.

So, we went and visited the place just for the fun of it. But I was told to take my portfolio, which I did. I was overwhelmed by the scale they were working on in there. But I showed my work and I was asked to take the job of illustrator there, which of course I did. Fortunately, I had such a good rapport with my director and art director on Ghostbusters that they allowed me to remain working for them full-time from home knowing that I had taken the other gig.

I have to take almost all jobs when they come in. Because what can happen is, the next project that was promised may never show up, and then I’m out of work. Which happens more often than you’d believe. This type of work is not for the faint of heart. It’s very tough. You never really know when you’ll be working or not. So you have to say yes to everything. The client that you have that loves you may, one day after working smoothly for weeks, just stop responding, and you’re done without notice. It makes it hard to take vacations. Heh...

HEAVY METAL: Can you talk a little bit about your process working on a property like Prometheus? What kind of aesthetic were you presented with, and what kind of ideas did that generate for you?

CARLOS HUANTE: For Prometheus in particular, the movie was “Alien prequel” and so we approached it as that. To start, my aesthetic bookends were Giger on one side and Giger on the other ;). I was going to make sure, whatever I did, that it would match up to Giger’s aesthetic. I wasn’t going to restyle the design language. In my opinion, all the new designs had to feel like Giger’s work. Ridley Scott had some ideas, but they were evolving. The idea of what would become the engineers were more like giant whales at first… less like humanoids... I had so many rounds of ammunition walking into that project that I was ready for a war.

I was essentially allowed to just run free. Ridley is such a good boss to have for a creative. He encouraged all my thinking and allowed me to speak to his ideas and add stuff. Whether they were used or not, in the end, is beside the point of the process being so organic. The “Deacon” literally came out of a drawing that I offered them in one round. I was thinking of a precursor to the Alien in the original film, and also the rules of why it existed as it did. I was writing notes on the plane before my meetings with Ridley, very fun stuff. Working on big, inspired movies like that is the best, there are very few. Men In Black, the first movie, was kind of like that as well because of Rick Baker. Rick Baker was equally a great boss. He allowed me to do whatever came into my mind and he shielded me from the politics of the studio. Denis Villeneuve was also one of those, and the situation on Arrival was so much fun. Denis and I pushed the ideas out and around to get as abstract, within reason, as we could...

HEAVY METAL: What kind of differences do you encounter working on a big blockbuster-type film project (AVP, Bladerunner 2, Fantastic Beasts 2) in comparison to working on a more genre or niche project (Arrival, Alice in Wonderland)?

CARLOS HUANTE: Those big blockbusters you mentioned had the luxury of already being established, which was a big challenge out of the way. Although working within established parameters can be a blessing or a curse, depending on how well the original project was designed. The source, or original versions of the those films you mentioned, fortunately, were all very, very well done, even iconic, which gave me an immediate and direct line for my imagination. Alice in Wonderland also is such a well-established story with illustrated books and the animated movie, again, iconic. Arthur Rackham, the poem of the Jabberwocky, and Disney in their heyday. Just great stuff. It was rich with established inspiration. Arrival is an example of a totally open-ended project that had no history and thus required a lot of thinking. Arrival-type projects are the hardest, but yield the biggest rewards.

HEAVY METAL: Have you had to expand and adapt your craft to work in video games, or do you find there is much in common with film and TV projects?

CARLOS HUANTE: There is a lot in common with all, although, with some minor approach shifts which make the distinctions between them all. So the creative approach is almost the same depending on the client, as in the director, art director, showrunner, VFX lead, producer, etc. and depending on whether whoever that person is that has the main voice on the project understands the project, and is able to communicate what the vibe of the project is, and/or, what they want.

HEAVY METAL: Who are your creative heroes? You mentioned that you’re a Bernie Wrightson fan...

CARLOS HUANTE: It’s a big list... but... just to name a few… yes, Bernie Wrightson. I really love his work. Muck Monster was probably the best period for me, personally. He had some of the Frankenstein in there, but with some of the fun, looser style from the earlier Swamp Thing. I loved all periods, but that one was my favorite of his.

I have to start this by saying that it was my older cousin, Johnny Vasquez, who inspired me to draw. He took the time to sit and draw with a child like me. My memory of his drawings are, “Wow”. He is my earliest artistic hero. I talk about him in my book Monstruo.

The very first art book I bought on my own (I was still a child) was Breaking the Rules of Watercolor by Burt Silverman. It is still one of my favorite art books. Then, my first book as a professional was The Art of Honore Daumier. The earliest professional influences for me were Alex Toth, Jack Kirby, and John Buscema. But then, Möebius, Giger, Gaetano Liberatore, Phillipe Druillet, Dali, Kent Williams, Bill Sienkiewicz, Richard Corben, Frank Frazzetta, Ray Harryhausen’s drawings as much as his FX animation work. Gustave Dore was/is huge to me, Beksinski, Stanislav Szukalski (one of the greatest). JMW Turner is a very big deal to me, Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky, Goya, Michelangelo, Bernini (the son), Leonardo, Rembrandt, Rodin, and Rembrandt Bugatti, and Paolo Troubetzkoy, who are everything to me as far as sculpture.

Announcements

Newsletter

Browse by tag

From the magnificent to the grotesque, from the dark to the darkly comedic, the non-human denizens of illustration, film, and TV haunt our dreams as expressions of far more than a mere mortal could convey. Their features, their bodies, their modes of physical communication are designed to speak to us, mostly without words, on a very deep level that conveys and carries story in a way that’s essential to many productions.

The question is: what makes a monster maker? How does someone learn that language and learn to evolve it in a way that brings something new to the conversation? A degree of nostalgia seems essential, looking back to the triumphs of creature creators of the past for inspiration, but it’s the innovators who are able to re-create the sense of wonder that we’re craving by bringing us something new.

Carlos Huante is a major innovator in the field of design, with over 30 years’ experience in the field, working on TV, film, and video game projects ranging from live action to animation, and all points in between. He’s handled some of the most beloved sci-fi and fantasy properties known to fans, from the Aliens franchise to Bladerunner, and ventured into new territory for big hits with Fantastic Beasts and Arrival.

Huante joins us for a significant walk down memory lane, as well as guided tour of his industry, to unveil just how one does become a designer of the alien and monstrous side of visual media.

HEAVY METAL: What do you think makes something a monster or monstrous? Are there certain traits that you think people expect from sci-fi monsters, particularly?

CARLOS HUANTE: I’ll tell you a story… (laughs) When I was starting school as a child, after first grade my parents decided to transfer me from public school to a parochial grammar school. The education was more advanced and I guess they thought with that, that it would keep me out of trouble... (laughs) I classically became an altar boy and would hang out with the priests sometimes for breakfast before a big service. I won’t tell you that I would sneak a taste of wine while putting the bottles away after service. I never had a bad experience with the priests. They were legit men and good people. My experiences were all, fortunately, great there.

A couple of summers later I went to a type of summer camp which was at Saint Vincent’s Seminary in California. I had the best time there. The brothers were very cool. We had game competitions through the week. Our group was made up of all the misfits, we were exactly like the “Bad News Bears”. The thing is, we won the competition against all the athletically blessed groups. It was an interesting thing to be a part of. So I bring this up for a reason. You’re wondering, “What does all this have to do with the question asked?”…Okay... one night was called “movie night”.

So we had our popcorn and punch, which the brothers called “bug juice”. The movie we watched was Night of the Living Dead. My first time seeing it… a scary movie right? No. The brothers’ reaction to the horror was to laugh at the absurdity. The worse the violence, the louder and more we all laughed. I laughed so hard watching that movie. It marked me for life. They taught me how much fun monster movies and the genre can be. That’s why I take it seriously. I think these movies and the sincere approach towards them gives people the ability to escape real life.

If Night of the Living Dead had been made in a very fake and uninvested manner, people would never have reacted towards it the way they did. It wouldn’t have allowed the hilarious reaction the brothers had at the seminary because it would’ve been stupid and uninteresting, but because they committed themselves to making it believable, it yielded a reaction. Some people got scared, some people laughed… either way the reaction was to the quality of the film and level of commitment. Monsters can be metaphorical, or straight takes on a character that’s written. Either way sincerity in the approach matters. My little part in the process is to design it. I take that part seriously...

HEAVY METAL: How important are tiny details, like bristles or scales, to you as an artist? What kind of overall impact do you think they have on a design or image?

CARLOS HUANTE: Details are secondary, or even tertiary. The most important hit is the first hit. Your first impression is based on primary shapes. When you see someone from far away that you know, you will usually recognize them, even amongst a crowd, because their form is their own. Primary form and proportions are the most important features of anything. That’s the personal base of that specific item, element or being. Details just float on top. Of course they will be much better, and flow with the form when they are handled correctly, but if the base is there, the detail should be pretty smooth sailing.

That being said, I’ve seen creatures ruined by contrasting details, contrasting in idea and personality. The work pipeline that is in use these days, where an artist designs the creature, then it’s passed onto the VFX house, often suffers revision by the many hands that handle it, sometimes unbeknownst to the client whose ability to see the difference is limited. Even if the design is declared as “The” design, the designer is out of the equation, so we can’t art direct to keep everyone in line with the original idea, and what you can end up with is contrasting surface detail and animation. I’ve suffered through this many, many times. Some instances made me feel physically ill for a couple days after seeing the final result in the film... that’s the byproduct of caring, unfortunately.

HEAVY METAL: You’ve been working as an artist for many years, so I know it’s a long story, but can you tell us a little more about how you became such a “monster guy”?

CARLOS HUANTE: I really loved science fiction growing up, as many do, but what I loved about it was the creativity meshed with the science. Of course, being a boy who hated sports, drawing and the arts in general were my outlet. I had many friends and participated in many activities, but as I grew older, I realized I enjoyed the solitude of playing a musical instrument or drawing.

I tried being in a rock band in high school and I just grew tired of the politics, and just wanted to be creative. So, I drifted off and away from that life fast. I liked drawing so much that I’d draw all the time. I loved cars when I was kid (I still do) thanks to my father. He was always buying trucks and/or vans back then and hot rodding them. It was a big reveal when it was finished. So, I drew them almost exclusively at first. The Munsters' “Drag-U-La” coffin car was a beautiful thing to me. That whole period was a great time for hot rods. The Batmobile, Hot Wheels toys… obviously this all lead me to Big Daddy Roth bubble gum cards… monsters and hot rods. But I quickly found that drawing monsters was where I wanted to go.

Once out of high school, and armed with many great sources of inspiration, I knew what I wanted to do for a living. The only problem was that I had no idea how to get in, and more importantly, the position didn’t exist yet. Although artists were hired to design creatures for film throughout film history, they were either makeup artists or generalists that worked in the art department, or Ray Harryhausen, who really only illustrated for his own projects.

Hollywood would later hire comic book artists like Moebius and Bernie Wrightson. When I saw Giger’s personal work, after my mind was blown by the film Alien, I realized two things: one thing was that I could still be an artist as a creature designer, which concerned me in the back of my mind. I had more in common with the type of artist Giger was. I had been a lifelong fan of Salvador Dali. I wasn’t necessarily a fan of dark art at all, but the creativity that had “thought” attached was what was so interesting...

HEAVY METAL: Do you prefer to work in a studio or in a more solitary way?

CARLOS HUANTE: I work from home most of the time, especially when I am drawing. I like to get lost in my own thoughts, but I do enjoy working directly with the client when they have the time. Those can be some of the best and most focused creative sessions while on a project. At the very least, if the budget permits, a good week session with the client after which I like to go off on my own…

HEAVY METAL: Can you tell us a little bit about your relationship with tactile media (pencils, ink, paint) versus digital? I’m assuming you have to work in digital a lot with design, but has that been a transition for you over time?

CARLOS HUANTE: I‘ll tell you... I got into all this because I like to draw. I like to sculpt. I am not someone who loves computers. That being said, I use them in a very limited way. I was a character art director at Industrial Light & Magic, so I understand the digital world, but I’m not really part of it. I see Photoshop as a tool to use in a traditional manner. I see 3D as a tool that I have used only a handful of times, but for nothing of any consequence, just as a token for the politicians in my business who believe it matters in the design phase. Which it doesn’t.

In recent years, I have been “regressing” to graphite on paper more and more, maybe out of rebellion against the digital wash-over the art world has suffered through. After all these years, drawing on paper is still the most honest medium to work in. You can’t hide a bad design with a line drawing. You have to draw every element of the design and you can’t get away with painting tricks, or digital atmosphere, or fancy lighting techniques... or for that matter, a turntable of a very conventional design in 3D. The design will have to sincerely be good naked, as a line drawing. If drawing was the only tool allowed, we’d elevate design in film by 50% at least… just with that one change.

Of course, that would eliminate a good deal of what I call imposters in the field these days… technicians posing as artists. This observation is purely out of love for what is being lost. The business is going through growing pains for sure. Digital has been the word in Hollywood, and most are the producers who just don’t know that digital is only a good production tool. It is not for initial design and ideation. It doesn’t save money in the design phase. Understand why this is a gripe. Imagine people who are not gifted sculptors or draftsmen, who merely know how to navigate the software, being given positions as designers. It’s artistically abominable. I know some of the best modelers in the world who agree with me. I love them for their part in the process, but not as designers. It disrespects them and their expertise and cheapens the entire process.

Years ago, when I was first coming up in the business as a professional, in the pre-digital era, I was critical about illustrators being hired to design creatures instead of designers. The illustrators would hide the design behind a render and lose most of the image in shadow, which makes for a dynamic and fun picture, but conceals the problems of the design. Design is a completely different expertise.

Then digital came along and turned that up to 100, and every child who could push a stylus flooded the business with regurgitated ideas from designs we had already done years prior. They still do. I see proportions and design elements on characters for jobs that are mere regurgitations of everything we came up with years ago, which suggests to me that there’s no thinking, integrity… no fire, no interest in anything other than getting a job, and/or recognition. It’s a shame. I know there are talented people out there, but they are not being pushed or required to do anything more than just achieve what has already been done and done successfully. It’s very boring. Once in a while I see something that’s interesting... but not as often as I’d like.

HEAVY METAL: How do you make a living in your field? Is it a case of taking on one big project at a time, or do you find yourself working on several at a time?

CARLOS HUANTE: Both. The unglamorous part is that I am making a living. In the last part of the ‘80s and first part of the ‘90s, what I would do is work for TV animation, designing characters during the TV season months, and then in off season, freelance for live action film. When I decided to get married, I was back working on the Ghostbusters animated series. While there, I met someone who knew people at a place called Dinamation. It was a place where animatronic dinosaurs were made for museums all around the world.

So, we went and visited the place just for the fun of it. But I was told to take my portfolio, which I did. I was overwhelmed by the scale they were working on in there. But I showed my work and I was asked to take the job of illustrator there, which of course I did. Fortunately, I had such a good rapport with my director and art director on Ghostbusters that they allowed me to remain working for them full-time from home knowing that I had taken the other gig.

I have to take almost all jobs when they come in. Because what can happen is, the next project that was promised may never show up, and then I’m out of work. Which happens more often than you’d believe. This type of work is not for the faint of heart. It’s very tough. You never really know when you’ll be working or not. So you have to say yes to everything. The client that you have that loves you may, one day after working smoothly for weeks, just stop responding, and you’re done without notice. It makes it hard to take vacations. Heh...

HEAVY METAL: Can you talk a little bit about your process working on a property like Prometheus? What kind of aesthetic were you presented with, and what kind of ideas did that generate for you?

CARLOS HUANTE: For Prometheus in particular, the movie was “Alien prequel” and so we approached it as that. To start, my aesthetic bookends were Giger on one side and Giger on the other ;). I was going to make sure, whatever I did, that it would match up to Giger’s aesthetic. I wasn’t going to restyle the design language. In my opinion, all the new designs had to feel like Giger’s work. Ridley Scott had some ideas, but they were evolving. The idea of what would become the engineers were more like giant whales at first… less like humanoids... I had so many rounds of ammunition walking into that project that I was ready for a war.

I was essentially allowed to just run free. Ridley is such a good boss to have for a creative. He encouraged all my thinking and allowed me to speak to his ideas and add stuff. Whether they were used or not, in the end, is beside the point of the process being so organic. The “Deacon” literally came out of a drawing that I offered them in one round. I was thinking of a precursor to the Alien in the original film, and also the rules of why it existed as it did. I was writing notes on the plane before my meetings with Ridley, very fun stuff. Working on big, inspired movies like that is the best, there are very few. Men In Black, the first movie, was kind of like that as well because of Rick Baker. Rick Baker was equally a great boss. He allowed me to do whatever came into my mind and he shielded me from the politics of the studio. Denis Villeneuve was also one of those, and the situation on Arrival was so much fun. Denis and I pushed the ideas out and around to get as abstract, within reason, as we could...

HEAVY METAL: What kind of differences do you encounter working on a big blockbuster-type film project (AVP, Bladerunner 2, Fantastic Beasts 2) in comparison to working on a more genre or niche project (Arrival, Alice in Wonderland)?

CARLOS HUANTE: Those big blockbusters you mentioned had the luxury of already being established, which was a big challenge out of the way. Although working within established parameters can be a blessing or a curse, depending on how well the original project was designed. The source, or original versions of the those films you mentioned, fortunately, were all very, very well done, even iconic, which gave me an immediate and direct line for my imagination. Alice in Wonderland also is such a well-established story with illustrated books and the animated movie, again, iconic. Arthur Rackham, the poem of the Jabberwocky, and Disney in their heyday. Just great stuff. It was rich with established inspiration. Arrival is an example of a totally open-ended project that had no history and thus required a lot of thinking. Arrival-type projects are the hardest, but yield the biggest rewards.

HEAVY METAL: Have you had to expand and adapt your craft to work in video games, or do you find there is much in common with film and TV projects?

CARLOS HUANTE: There is a lot in common with all, although, with some minor approach shifts which make the distinctions between them all. So the creative approach is almost the same depending on the client, as in the director, art director, showrunner, VFX lead, producer, etc. and depending on whether whoever that person is that has the main voice on the project understands the project, and is able to communicate what the vibe of the project is, and/or, what they want.

HEAVY METAL: Who are your creative heroes? You mentioned that you’re a Bernie Wrightson fan...

CARLOS HUANTE: It’s a big list... but... just to name a few… yes, Bernie Wrightson. I really love his work. Muck Monster was probably the best period for me, personally. He had some of the Frankenstein in there, but with some of the fun, looser style from the earlier Swamp Thing. I loved all periods, but that one was my favorite of his.

I have to start this by saying that it was my older cousin, Johnny Vasquez, who inspired me to draw. He took the time to sit and draw with a child like me. My memory of his drawings are, “Wow”. He is my earliest artistic hero. I talk about him in my book Monstruo.

The very first art book I bought on my own (I was still a child) was Breaking the Rules of Watercolor by Burt Silverman. It is still one of my favorite art books. Then, my first book as a professional was The Art of Honore Daumier. The earliest professional influences for me were Alex Toth, Jack Kirby, and John Buscema. But then, Möebius, Giger, Gaetano Liberatore, Phillipe Druillet, Dali, Kent Williams, Bill Sienkiewicz, Richard Corben, Frank Frazzetta, Ray Harryhausen’s drawings as much as his FX animation work. Gustave Dore was/is huge to me, Beksinski, Stanislav Szukalski (one of the greatest). JMW Turner is a very big deal to me, Ivan Konstantinovich Aivazovsky, Goya, Michelangelo, Bernini (the son), Leonardo, Rembrandt, Rodin, and Rembrandt Bugatti, and Paolo Troubetzkoy, who are everything to me as far as sculpture.